Approach to the Infant and Child with Feeding Difficulty

Richard J. Noel

Feeding includes food acquisition, ingestion, digestion, and absorption. This activity relieves hunger and provides multisensory stimulation, resulting in a pleasant, rewarding experience for both the child and the caretaker. Successful feeding experiences create positive reciprocal interactions that reinforce the bonding relationship between child and caretaker. Feeding disorders prevent the infant from ingesting adequate nutrients for continued health, growth, and development.

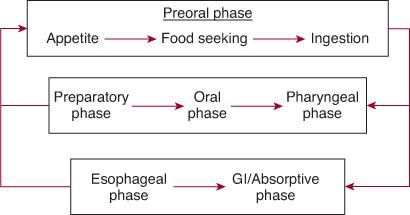

Feeding and swallowing are complex processes that can be divided functionally into 4 phases, as shown in Figures 31-1 and 31-2. The preoral phase is initiated when the child senses and communicates hunger. The oral phase is a food-processing step wherein the ingested material is formed into a bolus that can safely pass through the pharynx; the remainder of the swallowing process is involuntary and reflexive. The pharyngeal phase is quite rapid. It is initiated by bolus contact with the tonsillar pillars and pharyngeal wall with subsequent elevation of the larynx, vocal cord closure, and relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter. A peristaltic wave of contraction of the pharynx propels the bolus into the esophagus.

FIGURE 31-1. Model of the normal phases of feeding in infants and children. Complex interactions between phases often obscure diagnosis of the primary cause of a feeding disorder.

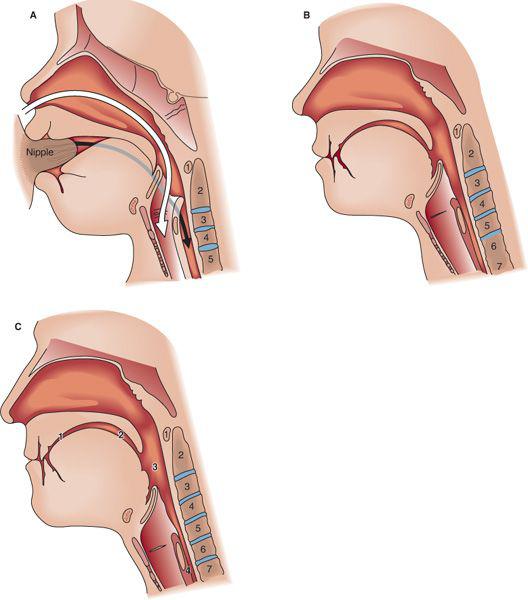

FIGURE 31-2. A: The infant oropharynx. The larynx is elevated with the epiglottis touching the soft palate, creating a functional separation between the air passages (white arrow) and the food passages (black/gray arrow) in the pharynx. Food courses around the epiglottis, into the pharyngeal recess, and then to the esophagus. B: The toddler (2–3 years old) oropharynx. C: The adult oropharynx: (1) oral preparatory phase, (2) oral phase, (3) pharyngeal phase, (4) esophageal phase. Note that the infant oral cavity is much smaller than the child or adult oral cavity, providing little space for manipulation of the food bolus. The larynx is elevated so that the epiglottis almost touches the soft palate, and the larynx is at the level of the first to third cervical vertebrae. The tongue is entirely within the oral cavity, with no oral region of the pharynx. In the toddler, the larynx descends to the fifth cervical vertebra, and by adulthood it descends to the sixth to seventh cervical vertebra.

During passage of the bolus through the pharynx, excellent coordination between breathing and swallowing is essential to prevent aspiration. In the esophageal phase, the bolus is transported into the stomach. Finally, the bolus is broken down and absorbed during the digestive phase. Developmental and maturational changes in the phases of swallowing occurring from infancy to childhood can have a significant impact on a child’s ability to feed successfully.

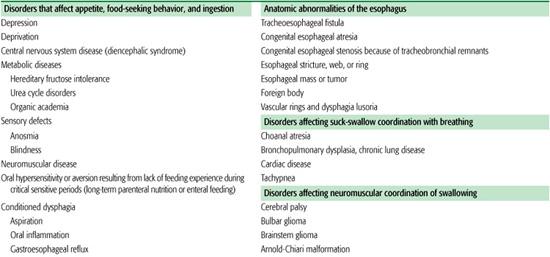

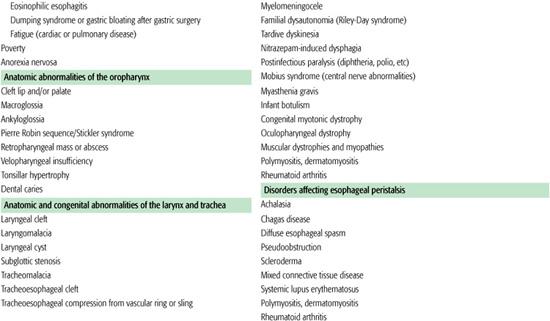

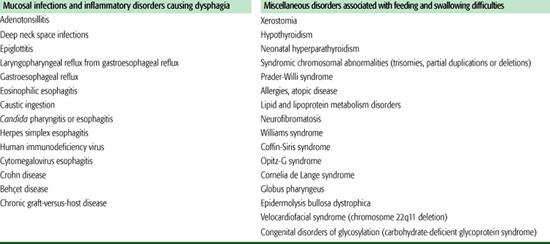

Symptoms of feeding and swallowing disorders in children have many manifestations and clinical presentations, anywhere from food refusal, failure to gain weight, and oral aversion to recurrent pneumonia, chronic lung disease, and recurrent emesis. Swallowing and feeding disorders in infants and children are complex and can have multiple etiologies; these are listed in Table 31.1. Organic and nonorganic etiologies occur alone or in combination, making the diagnosis and treatment challenging and complicated. Feeding and swallowing can be interrupted in any phase. Successful management of the child with feeding problems begins with the identification and treatment of any correctable underlying physical cause of the feeding disorder. Identifying and addressing both parent and patient nonorganic behavioral factors occurring concurrently with a physical cause will enhance management. Only after all reasonable physical etiologies have been ruled out should a feeding or swallowing disorder be attributed to a nonorganic cause.

PREORAL PHASE

APPETITE

APPETITE

Centers for hunger and satiety in the hypothalamus receive afferent signals from a variety of sources. Sensory inputs that affect feeding behavior are well developed even in infants. Appetite also is affected by emotional state: Infants who are not nurtured reduce their food intake and fail to thrive. Reductions in appetite are frequent in infants and children with chronic debilitating disease; however, very specific food aversions may be observed in otherwise healthy people. If ingestion of a specific food is temporally associated with a painful or uncomfortable experience, a child may refuse to ingest that food again. This type of specific aversion is observed in patients with metabolic disease, gastroesophageal reflux, or allergies who experience nausea or discomfort after ingesting offending nutrients (eg, as seen with ingestion of sucrose in patients having hereditary fructose intolerance). More generalized feeding aversions can occur if an infant has negative experiences such as aspiration or choking during feeding. Infants who have required prolonged airway intubation or tube feeding often learn that efforts by a caretaker to approach their mouth or face likely result in discomfort, and “oral defensiveness” can persist long after the patient is extubated.

FOOD SEEKING AND INGESTION

FOOD SEEKING AND INGESTION

Preverbal infants and developmentally delayed children communicate hunger by providing behavioral cues to their provider; in turn, the caretaker must correctly interpret these cues. If the caretaker misses the cue and offers food when the child is not interested in eating, the resultant struggle can easily exacerbate the situation. In toddlers, food seeking consists of communicating hunger. Efforts to independently use a spoon and cup and, ultimately, to obtain food from the refrigerator themselves progress through development. In adults, food seeking is a complicated process that includes most aspects of our daily lives. The mechanical process of ingestion requires the appropriate muscular coordination and sensation to bring food to the mouth. This is a learned process that evolves through normal development. Neuromuscular disorders, blindness, and fatigue resulting from illness all can interfere with food ingestion.

Table 31-1. Partial List of Medical Etiologies of Feeding Disorders in Children by Category

Infants with subtle feeding disorders are less resilient in responding to difficult environments and emotional deprivation than are normal infants. Many children who have been diagnosed with failure to thrive have subtle neuromuscular or oromotor disorders. Successful management in this setting requires teaching caretakers how to adjust feeding techniques appropriately. Continued unsuccessful efforts to feed the child can disrupt the caretaker-child relationship even in well-adjusted families.

SWALLOWING

ORAL PHASE

ORAL PHASE

The oral phase consists of bolus formation and movement of a food substance posteriorly toward the pharynx. Oral phase development begins at 15 weeks of gestation with mouthing and suckling movements. By 32 weeks, a disordered pattern of suckling bursts and pauses emerges. By 34 to 36 weeks, the fetus displays a stable pattern of rhythmic suckling and swallowing. After birth, swallowing is triggered when a certain volume of fluid occupies the oral cavity. Excellent tongue motion and coordination are needed for this phase of swallowing.

During postnatal development, anatomic changes occur in the oral cavity with concurrent development and maturation of motor skills required for safe feeding (see Figure 31-2). In infancy, the oral phase of swallowing consists of the subcortically regulated process of suckling, characterized by primitive extension-retraction motion of the tongue. The small size of the mandible and oral cavity relative to the tongue and the presence of buccal fat pads facilitate suckling and provide an ideal geometry for generating suction on a nipple but leave little room or ability for manipulation of a solid bolus. Food delivery is accomplished by sealing the lips around the breast or nipple and then sealing the posterior aspect of the oral cavity with the tongue against the palate. Depressing the oral surface of the tongue creates suction pressure for bolus delivery. Suction pressures greater than 100 mm Hg are generated in the oral cavity of healthy newborns, with the amount of pressure varying to adjust the flow rate to approximately 0.2 mL per suck. Too rapid a flow results in overflow of milk into the pharynx before the initiation of an organized swallow, with the potential for aspiration.

Between 3 and 6 months of age, the anatomy of oral cavity and pharynx begins to change, and infants start to suppress the suckle pattern and develop voluntary suck patterns. The anatomical changes include resorption of the buccal fat pads and the inferior and forward drop of the jaw, thus increasing the intraoral space. Tongue movements mature from extension-retraction motion of suckling to up-and-down movements of sucking, facilitating bolus manipulation and thereby allowing for a more coordinated transport of food and liquid into the oral cavity. This maturation in skills allows infants to begin eating textured food from a spoon by 4 months of age. Masticatory skills begin to develop by 6 to 8 months and continue to develop as the alveolar ridges mature and deciduous teeth erupt. At 12 months, suckling patterns are minimized, and children generally transition to cup drinking and no longer use the suck pattern. By 18 to 24 months, rotary chewing skills and increased lateral activity of the tongue contribute to more effective handling, crushing, and grinding of food.

Specific oral skills such as sucking or chewing solids are learned only at certain ages. Infants who do not orally feed during these critical periods of development have a difficult time mastering these skills later; these patients may learn how to spoon and cup feed without ever learning to suck effectively. Development of the oral phase requires normal anatomy, intact sensory feedback, and normal muscle strength and coordination. Anatomic defects include cleft lip with or without cleft palate, micrognathia, and macroglossia. A weak suck may be congenital or acquired. Other causes of oral-phase dysfunction include xerostomia and temporomandibular joint pathology.

PHARYNGEAL PHASE

PHARYNGEAL PHASE

The pharyngeal phase of swallowing is involuntary and is triggered by bolus contact with the tonsillar pillars and pharyngeal wall. During pharyngeal swallowing, the upper pharynx and soft palate close to seal the nasal cavity as the bolus enters the pharynx. The bolus is propelled to the esophagus by contraction of the pharyngeal muscles. Proprioceptive feedback adjusts this activity as needed to compensate for different types of boluses. During pharyngeal contraction, the larynx elevates, the vocal cords close, and respiration ceases to protect the lower airway from aspiration. The upper esophageal sphincter relaxes, and peristaltic contractions of the pharynx push the bolus past the displaced, closed larynx into the upper esophagus. Because the pharynx is the common chamber for the respiration and digestive pathways, important developmental changes occur to allow for safe swallowing. In the infant, the larynx sits high in the neck at the level of vertebrae C1-3, allowing the velum, tongue, and epiglottis to approximate and thereby functionally separate the respiratory and digestive tracts. This allows the infant to safely breathe and feed. Even though this unique functional separation exists in infants, vigorous sucking and swallowing during feeding can cause significant reductions of minute ventilation and mild hypoxia even in healthy babies. Babies with compromised cardiac or respiratory function may have serious difficulties with hypoxia during feeding.

By age 2 to 3 years, the larynx descends, decreasing the separation of the swallowing and digestive tracts. Intact oral motor skills and laryngeal function are essential for coordinating the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing to prevent complications of aspiration. Early overflow of the bolus into the pharynx before respiration ceases may allow food to enter the trachea during inspiration. Lack of relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter causes pooling in the piriform sinuses with resultant food overflow into the airway when the larynx descends at the end of the swallow sequence and inspiration begins. Because there is less separation of the swallowing and digestive tracts at this developmental stage, subtle anatomic or neuromuscular disorders that are not problematic in an infant can cause recurrent aspiration in a toddler.

Laryngopharyngeal sensory deficits from neurologic disorders or decreased laryngeal sensitivity from chronic extraesophageal gastroesophageal reflux predispose to problems with coordinating swallowing and increase aspiration risk. Congenital abnormalities, including laryngeal clefts and laryngomalacia, can result in dysphagia and aspiration. Myopathies, central nervous system abnormalities, tumor masses, foreign bodies, esophageal peristaltic disorders, and inflammation can disrupt the pharyngeal phase of swallowing. As noted previously, infants or children with tachypnea or cardiac compromise often have difficulty coordinating swallowing and breathing, thereby making feeding more difficult.

ESOPHAGEAL AND GASTROINTESTINAL PHASES

ESOPHAGEAL AND GASTROINTESTINAL PHASES

Abnormal peristalsis, esophageal inflammation from gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic esophagitis, infection, allergy, and mechanical obstruction may all cause dysphagia. Odynophagia or postprandial pain or discomfort from any gastrointestinal disorder may result in the development of feeding aversions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree