Anxiety

Denise A. Chavira

Fear is an emotional response that is a normal part of development and essential to human survival. It is both protective and adaptive. In times of danger or anticipated risk, the sympathetic nervous system is activated and prepares the body to fight or flee the dangerous situation. Fear is short lived, which makes it different from mood states such as anxiety. Anxiety is often thought of as a secondary emotion in response to a primary emotional reaction (eg, fear). For example, people become anxious if they are fearful about a specific event, object, or situation and anticipate negative outcomes. Anxiety requires more cognitive capacities than fear. The fight-flight response may be activated when anxiety and fear appear even when there is no real danger but negative outcomes are anticipated. Such anticipatory fear, when persistent and pervasive, extends beyond normative levels of fear and anxiety and can be debilitating.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

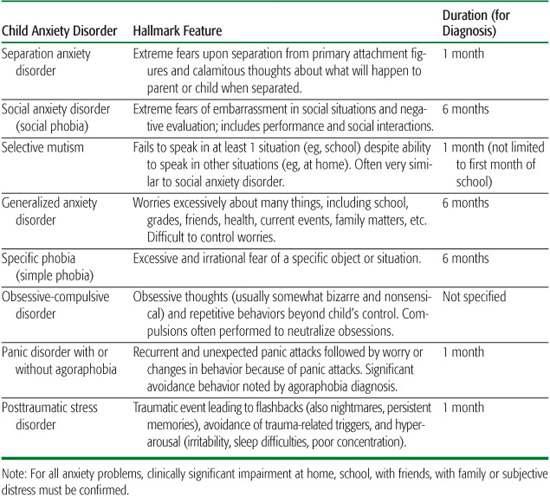

The focus of fear and anxiety changes through development as infants and children explore their world, encountering new situations and stimuli. Fears and anxiety are manifested in various ways. Some children may appear visibly nervous. Others may hide their feelings, freeze in a situation, or express their anxiety as anger or frustration. While many children experience anxieties and worries at some point in their lifetime, most do not have clinical disorder. Normative and problematic anxiety can be distinguished in various ways (see eTable 88.1  ); ultimately, however, it is often the degree of interference and distress that determines whether a child has a clinical anxiety disorder. Specific types of anxiety disorders are distinguished by hallmark features (see Table 88-1).

); ultimately, however, it is often the degree of interference and distress that determines whether a child has a clinical anxiety disorder. Specific types of anxiety disorders are distinguished by hallmark features (see Table 88-1).

Anxiety disorders can be described with reference to 3 realms: physiological, behavioral, and cognitive. Physiological reactions to feared stimuli include increased heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, sweating, flushing, nausea, diarrhea, tingling sensations, abdominal problems, dry mouth, lightheadedness, dizziness, muscle tension, tremors, and chest pain. Behavioral signs of anxiety typically include avoidance, social withdrawal, irritability, angry outbursts, crying, clinginess, insomnia, nightmares, distractibility, hyper-vigilance, and cautiousness. Cognitively, children with anxiety often have an attentional bias toward threat-related information with a tendency to fear the worst and exaggerate risks.

CONTINUA OF ANXIETY: FROM FEARS AND WORRIES TO ANXIETY DISORDERS

CONTINUA OF ANXIETY: FROM FEARS AND WORRIES TO ANXIETY DISORDERS

Clinginess to Separation Anxiety Disorder

Many children feel anxious when separated from their parents or other caregivers. Separation anxiety is most common between 1 and 3 years of age and mostly resolved by age 5. Thereafter, separation anxieties would be expected only occasionally, such as when starting a new school year or going away to camp; typically, however, these fears are very temporary, usually lasting 2 to 3 days for most children and 2 to 3 weeks for others. Children with separation anxiety disorder worry about being away from their parents during school, at bedtime, or even when their parents are in a different room. Often, they worry that something bad will happen to them or to their parents while they are separated. Impairment may include numerous missed opportunities (eg, camp, sleepovers, social activities), school avoidance, and sleep problems. As a rule of thumb, if separation fears persist longer than 1 month without any signs of improvement and are severe enough to cause some type of impairment, then a clinical disorder might be suspected.

Shyness to Social Anxiety Disorder

Shyness is a common childhood trait and should not be considered a clinical disorder unless it is persistent, excessive, and causes some type of impairment. Behavioral inhibition,1,2 a temperamental characteristic similar to shyness, is a stable trait in approximately one third of infants. Children with an inhibited temperament have been found to be timid with novel or unfamiliar people, objects, and situations, while uninhibited children spontaneously approach these stimuli. These behavioral differences are accompanied by physiological differences, including increased heart rate and heart rate variability, pupillary dilation during cognitive tasks, vocal cord tension when speaking under moderate stress, and salivary cortisol levels among the behaviorally inhibited children. When behavioral inhibition is persistent and stable, a child is at increased risk for anxiety disorders, specifically social anxiety disorder.3

Table 88-1. Hallmark Features of Child Anxiety Disorders

The hallmark feature of social anxiety disorder is the excessive concern about negative evaluation and embarrassment in front of others. This persistent fear is accompanied by increased physiologic arousal and avoidance of social situations like parties, meeting new children, starting a conversation, speaking in class, and giving speeches. Parents often describe children with social anxiety as being overly sensitive to criticism and rejection as well as nonassertive with peers. Common types of impairment include lack of friends, loneliness, poor school performance related to lack of participation, school refusal, and low self-esteem. This disorder is discussed in more detail in Chapter 72 since it tends to emerge between the ages of 11 and 19 years.

Selective mutism is similar to a social anxiety disorder. Children with selective mutism are reticent to speak in certain situations, and they consistently fail to speak in 1 or more social settings (eg, school) despite speaking normally in other settings (eg, home). They do not warm up after a brief period and start speaking, although they may engage in nonverbal gestures. Selective mutism can lead to various problems in school (eg, not answering questions, not requesting to go to the bathroom), difficulty making friends, family arguments (eg, child will not speak when requested to speak), and caregiver strain.

Routine Worries to Generalized Anxiety Disorder

All children have occasional worries; however, when the worries become excessive and uncontrollable, they are no longer considered normative. Children with generalized anxiety tend to worry much more than other children their age, and they are unable to stop worrying. They may worry about their grades, homework, friends, their health, the health of others, things going on in the world, and family matters, among other things. Such children worry even when there is no realistic reason to be concerned. Insomnia, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, and irritability are common complaints among children with generalized anxiety disorder. Other forms of impairment may include a general inability to enjoy life because of constant worries, difficulty maintaining friendships, school problems related to concentration difficulties, and, occasionally, medical problems. For a more detailed discussion of the diagnosis and treatment of generalized anxiety disorders see Chapter 72.

Fears to Phobias

Fears are common during childhood and generally dissipate over time and with experience (direct experience and reassuring information from others). Fears that are considered phobias persist despite experience and reassurance and are associated with intense distress or avoidance of the phobic object or situation. The DSM-IV TR divides specific phobias into 5 categories: animal, such as fear of spiders (arachnophobia); natural environment, such as fear of lightning and thunderstorms (astraphobia); situational, such as fear of enclosed spaces (claustrophobia); blood-injection-injury, such as fear of needles (trypanophobia); and other, such as fear of school (scolionophobia). The onset of a specific phobia is usually in childhood or adolescence. The lifetime prevalence of a specific phobia is 12.5%; the 12-month prevalence is 8.7%.3a The etiology may be trauma; for example, being bitten by a dog may result in an irrational fear of dogs. Phobias may be acquired socially, as in fear of foreigners, or xenophobia. Specific phobias may also be rooted in biologic or genetic susceptibility toward anxiety. The treatment of specific phobia is nonpharmacologic. Cognitive behavior therapy with graduated exposure to the source of fear is the preferred treatment.

Habits to Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Habits and rituals are common during childhood. For example, children may have certain ways of arranging their toys, want to wear a favorite shirt, or have various bedtime rituals that they enjoy. The obsessions and compulsions that make up obsessive-compulsive disorder, however, are more involuntary, less enjoyable, and somewhat bizarre and nonsensical in nature. Obsessions come in varying forms, including fears of contamination, need for order or symmetry, pathological doubting, and recurrent aggressive or horrific images. Common compulsive behaviors include washing, checking, counting, ordering, asking for reassurance, and repeating words or actions. Often, children engage in compulsions to neutralize the unwanted thoughts. For example, a child may think, “Everything must be lined up perfectly, or something bad will happen to my mother,” and therefore engage in excessive ordering rituals to prevent the bad event. Compulsions are more dominant in younger children, while obsessions in this age group tend to be more vague (eg, “I had to wash my hands because I just didn’t feel right”). Obsessions and/or compulsions must consume at least 1 hour per day and cause marked distress and/or significant impairment to be classified as obsessive-compulsive disorder. Like most of the anxiety disorders, obsessionality exists on a continuum where it is possible for a child to have traits even if he or she does not have the disorder. For further discussion see Chapter 72.

Panic Attacks to Panic Disorder

Panic attacks include symptoms (usually 4 or more at the same time) such as a racing heart, sweating, shaking, shortness of breath, feelings of choking, chest pain, chills, nausea, dizziness, fear of losing control or going crazy, and fear of dying. Children with or without an anxiety disorder can have panic attacks. For example, children with social anxiety disorder often have panic attacks in public speaking situations but do not necessarily have panic disorder. Similarly, a child without an anxiety disorder may have an occasional panic attack in a given situation but not have panic disorder. The hallmark feature of panic disorder is a recurrent pattern of unexpected panic attacks that come out of the blue and do not have a specific trigger. Panic disorder is associated with subsequent worry about having another panic attack or a change in behavior because of worries about having another panic attack. The presence of a behavior change related to the panic attacks often results in the additional diagnosis of agoraphobia in which a child avoids certain places (eg, malls, crowded places, being in a car) for fear that they may have a panic attack and not be able to escape or get help. Panic disorder usually begins in late adolescence and is uncommon among young children.

Stressful Experience to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Approximately 15% to 35% of children will experience a traumatic event in their lives; however, most will not develop a stress disorder on account of this. Children with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) experienced a traumatic event (eg, varying forms of abuse, a tragic accident, fire, earthquake or other natural disaster, violent crimes, seeing somebody else being hurt) that was upsetting, frightening, life threatening, and outside the realm of a normal childhood experience. In response, the child reacted with intense fear, helplessness, or horror. A child with PTSD experiences flashbacks or recurrent images in the forms of dreams or memories as well as avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma. Younger children may exhibit these behaviors in their play or in their drawings. Various forms of physiological arousal also become prominent after the trauma, including irritability, difficulty concentrating, hypervigilance, difficulty with sleep, and an exaggerated startle response. Related to PTSD is acute stress disorder, which also occurs specifically in response to a traumatic event but is different in that the symptoms must occur within 4 weeks of the trauma and resolve within those 4 weeks. For further discussion see Chapter 72.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Anxiety symptoms are seen in patients with other medical and behavioral conditions, including substance abuse disorder, autistic spectrum disorders, attention deficit hyper-activity disorder (ADHD), and adjustment disorder.

Symptoms of anxiety such as chest pain, insomnia, dizziness, headaches, shortness of breath, nausea, palpitations, and numbness may mimic medical illnesses such as cardiac disease (eg, mitral valve prolapse in an adolescent and arrhythmias), hypoglycemia, pheochromocytoma, vestibular dysfunctions, hypercortisolism, growth hormone deficiency, thyroid disorders (hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism), pulmonary problems, and seizure disorders. It may be challenging for clinicians to recognize anxiety disorders. Diagnostic accuracy can be facilitated by considering the context, frequency, and duration of the child’s anxiety symptoms as well as atypical features such as age of onset, course, and absence of a family history of anxiety.

Anxiety usually predates depression and is often associated with the onset of depression (see Chapter 93). For example, a socially anxious child who does not have friends and cannot engage in social activities may experience feelings of loneliness and low self-esteem and subsequently become withdrawn and depressed. Where there is anxiety, a clinician should also ask about depression, and vice versa. Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (see Chapter 92) are often distracted by extraneous stimuli (eg, random noises, other kids, trying to get homework done to move on to something more fun), whereas children with anxiety disorders are distracted by worries and fears (eg, thoughts like “What if I say the wrong answer,” “What if my work is not good enough”) or by rituals, compulsions, or flashbacks.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In community samples of nonreferred children, prevalence rates of anxiety typically range from 10.7% to 17.3%, and rates are usually higher in girls and younger children. In pediatric primary care settings, 1-year prevalence rates of anxiety disorders among children ages 7 to 11 range from 6.6% to 10.5% based on parent and child reports respectively.4,5

Childhood anxiety is associated with loneliness, educational underachievement, and low self-esteem.9-10 Also, anxiety may intensify the impact of co-occurring disorders such as ADHD, making treatment more complex. In addition, child anxiety disorders are often associated with gastrointestinal problems, asthma, and headaches,11-12 potentially increasing physician visits and costs.

ETIOLOGY

GENETIC AND BIOLOGICAL INFLUENCES

GENETIC AND BIOLOGICAL INFLUENCES

Family history studies that have examined anxiety in children of adults with anxiety disorders and parents of children with anxiety disorders have found rates of anxiety disorders in family members to be higher than in the general population. Twin, sibling, and adoption studies show that genetics explain approximately one third of the variance associated with child anxiety disorders.13 In a study that delineated types of anxiety related behaviors and included 4564 pairs of 4-year-old twins, contributions for general distress, separation anxiety, and fear were modest, while the contributions for obsessive-compulsive behaviors and shyness/inhibition were substantial (heritability estimate was 62%). Specific genes implicated in anxiety include serotonin and dopamine genes; however, it is likely that multiple genes are involved. Vulnerability to anxiety likely exists along a continuum, and quantitative assessments of dispositional characteristics (eg, temperamental characteristics such as neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity, and behavioral inhibition) may be most informative when trying to understand genetic transmission.14

ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES

ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES

While studies have been somewhat consistent in demonstrating that child anxiety is heritable, shared and nonshared environmental factors also have significant influences in explaining child anxiety. Shared influences include those factors that make family members similar to each other, while nonshared environment includes those factors that make an individual unique (eg, recent stressful life events, friendships, school performance, danger events). A child may be predisposed to anxiety, while the environmental (shared and nonshared) factors facilitate the actual expression of the disorder. This is further supported by the finding that children who have a parent with an anxiety disorder are at risk for developing an anxiety disorder but not necessarily the same disorder as the parent.13 Conditioning experiences, modeling, family environment, and parenting styles often play a significant role in shaping the phenotype of an anxiety disorder.

DETECTION AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The use of brief screening questions may increase quality of communication between clinicians and parents about children’s behaviors and facilitate detection. The Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED)21 is a 5-item questionnaire useful to screen for generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and school phobia (see Table 88-2).

When the screening test is positive, a clinician should gather additional information about severity and impairment, including a medical and developmental history, family history of anxiety and depression, school history, social history, and any changes in the past year. Basic questions should be asked concerning the situations in which the anxiety occurs, how often it happens, what the child is afraid might happen in the situation, how the family manages the anxiety when it occurs, and severity of anxiety. Also, information should be gathered regarding anxiety-related impairment at school (eg, number of absent or tardy days, impaired academic performance, school refusal), with friends (eg, trouble making or keeping friends), with family (arguments or restricted activities because of child’s anxiety), and child’s or parent’s own distress about the anxiety. If anxiety appears to be chronic, pervasive, and associated with significant impairment, a referral to a mental health provider should be considered. In cases of mild to moderate anxiety, the child’s primary care clinician can initiate a treatment plan.

Table 88-2. Screening for Anxiety in Primary Care: The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED)