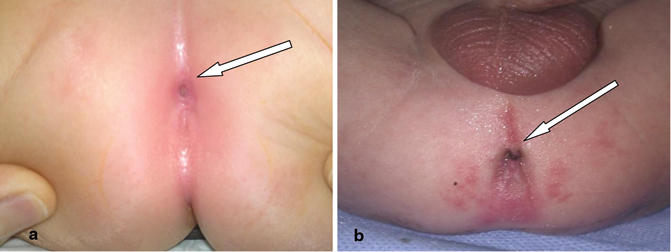

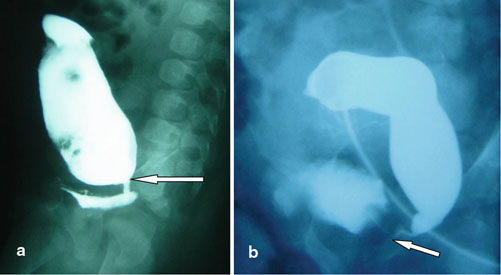

Fig. 54.1

Clinical photograph of two patients with high anorectal malformations. Note the flat perineum and absence of fistula

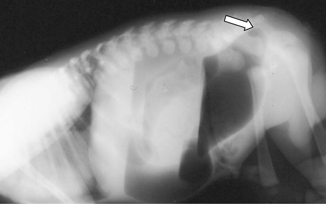

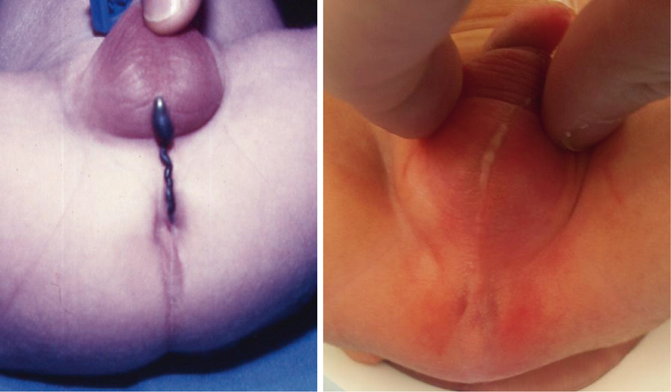

Fig. 54.2

A clinical photograph of a patient with low anorectal agenesis. Note the perineal fistula (a) and the meconium passing through a perineal fistula (b)

Fig. 54.3

A clinical photograph showing the bucket-handle deformity

The presence of meconium at the perineum

A bucket-handle malformation (a prominent skin tag located at the anal dimple, below which an instrument can be passed)

An anal membrane (through which meconium is visible)

The presence of a single perineal orifice in a patient is clinical evidence of a persistent cloaca.

In 80–90 % of newborn boys, clinical evaluation and urinalysis provide enough information for the surgeon to decide whether a colostomy is required.

Meconium is not usually observed at the perineum in a newborn with rectoperineal fistula until at least 16–24 h of life.

Abdominal distension does not develop during the first few hours of life but is required to force meconium through a rectoperineal fistula, as well as through a urinary fistula (Fig. 54.4).

Fig. 54.4

A clinical photograph showing abdominal distension in a newborn with high anorectal agenesis

It is also important to note whether there is meconium in the urine.

Investigations

Imaging studies performed in the newborn period include the following:

Abdominal ultrasonography to evaluate urologic anomalies.

Plain radiography of the spine may reveal spinal anomalies, such as spina bifida and spinal hemivertebrae.

Plain radiography of the sacrum in the anterior-posterior and lateral projections may demonstrate sacral anomalies, such as a hemisacrum and sacral hemivertebrae. In addition, the degree of sacral hypodevelopment may be assessed and a sacral ratio can be calculated (the distance from the coccyx to the sacroiliac joint divided by the distance from the sacroiliac joint to the top of the pelvis; Fig. 54.5).

Fig. 54.5

Diagrammatic representation of calculating the sacral ratio

Spinal ultrasonography in the newborn to find evidence of a tethered spinal cord and other spinal anomalies.

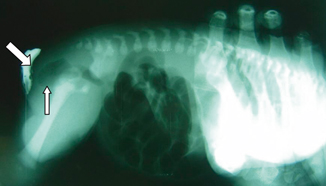

Cross-table lateral radiography may help demonstrate the air column in the distal rectum (Fig. 54.6).

Fig. 54.6

A lateral radiograph of a patient with anorectal agenesis. Note the air column in the distal rectum

Obtain cross-table lateral radiographs with the newborn prone, with the pelvis elevated, and with a radiopaque marker placed on the perineum. This is done 16–24 h post delivery.

Rarely, radiography reveals the column of air in the distal rectum to be within 1 cm of the perineum; in these instances, treatment is similar to that for rectoperineal fistula and a newborn perineal operation may be performed.

If the air column is more than 1 cm from the perineum, a colostomy is indicated (Fig. 54.7).

Fig. 54.7

A lateral radiograph showing the air column in the distal rectum. Note the distance between the distal air and site of the marked anus

Classification

The traditional classification of anorectal malformations divides them into:

High

Intermediate

Low

This was based on the relation of the terminal end of the bowel remaining above (high), within (intermediate), or below the levator ani muscle (pelvic floor) which is the main muscle of continence.

Invertogram in a dead lateral position with the hips slightly flexed gives accurate information regarding the nature of the anomaly.

The radiological landmarks used for this purpose are the pubococcygeal line (PC line; a line between the pubis and the coccyx) and the I point (tip of the ischium) to which the air shadow of the terminal end of the bowel is correlated. The measurements used are:

If the air shadow crosses the (I) point, it is a low anomaly.

If it crosses the PC line but stops short of the (I) point, it is an intermediate anomaly.

If the air shadow of the terminal end of the bowel stops above the PC line, it is a high anomaly.

This was replaced by a simpler measurement depending on the distance between the end of the gas shadow in the terminal end of the colon and the mark placed at the site of the future anal opening. In high defects, the distance is more than 1 cm while in low defects the distance is less than 1 cm.

Subsequently, anorectal malformations were classified anatomically as shown in Table 54.1.

Table 54.1

Classification of anorectal malformations

Sex

Male

Female

Type of anomaly

Rectoperineal fistula

Rectoperineal fistula

Rectourethral fistula

Rectovestibular fistula

Rectobulbar fistula

Rectoprostatic fistula

Rectovesical fistula (bladder neck)

Persistent cloaca

< 3 cm common channel

> 3 cm common channel

Imperforate anus without fistula

Imperforate anus without fistula

Rectal atresia

Rectal atresia

Complex defects

Complex defects

In boys, 85 % have a rectourinary fistula and 35 % have a rectoperineal fistula, while 93 % of girls have an external fistula (Figs. 54.8 and 54.9).

Fig. 54.8

a and b, A loopogram showing a rectovesical fistula in two patients with high anorectal fistula

Fig. 54.9

Clinical photographs showing rectoperineal fistula in males. Note the meconium passing subcutaneously to the scrotum

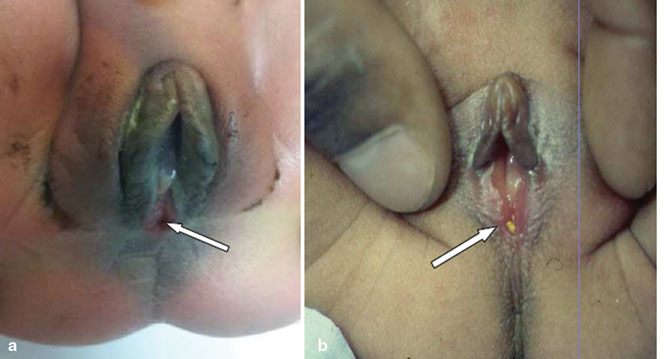

The most common defect in females is rectovestibular fistula (Fig. 54.10).

Fig. 54.10

a and b, Clinical photographs showing rectovestibular fistula (arrows)

Table 54.1 lists the classifications of anorectal malformations. Figures 54.11, 54.12, 54.13, 54.14, 54.15, 54.16, 54.17, and 54.18 illustrate these malformations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree