Amenorrhea

David P. Cohen

Amenorrhea is defined as either the absence or cessation of menses. It is a common symptom and may be anatomic (developmental or acquired), organic, or endocrinologic in nature. This chapter outlines the differential diagnosis of amenorrhea, the indications and methods of evaluation, and options for treatment once a diagnosis is clearly defined. The most common cause of amenorrhea in women of reproductive age is pregnancy, which should always be excluded before considering other etiologies.

The Normal Menstrual Cycle

Normal cyclic menstruation comprises a complex integration of endocrine signals, involving autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, operating at four distinct levels: the genital tract, the ovary, the pituitary gland, and the hypothalamus. First, a normal and patent genital outflow tract is necessary. The uterus must have functional endometrium capable of responding to estrogen and progesterone and be contiguous with a patent cervix, vagina, and introitus. Second, the ovaries must contain follicles responsive to pituitary follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) stimulation. The two-cell gonadotropin mechanism of steroidogenesis explains how FSH and LH, together with follicular theca and granulosa cells, orchestrate the production steroids by a dominant follicle. It also describes how a dominant follicle is selected from a cohort of developing follicles in the later half of the follicular phase. In summary, each follicle competes for FSH, and the follicle best able to exploit the diminishing FSH in the early follicular phase is selected. Third, pituitary gonadotrophs must have the capacity to synthesize and secrete gonadotropins in response to pulsatile hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulation. The relative amounts of FSH and LH released reflect changes in the pulsatile pattern of GnRH secretion and the feedback modulation by ovarian steroid and peptide hormones. Finally, specialized neurosecretory cells located in the medial basal hypothalamus (arcuate nucleus) must communicate with the pituitary gland by synthesizing and releasing GnRH in a pulsatile pattern into the hypophyseal portal system, which responds to stimuli from the environment and feedback signals from peripheral endocrine organs.

Amenorrhea may result from congenital or acquired disease or dysfunction at the level of the genital tract, the ovary, the pituitary, or the hypothalamus. In fact, the single most common cause of amenorrhea—chronic hyperandrogenic anovulation (polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS])—involves a number of interrelated pathophysiologic mechanisms that operate at the ovarian, pituitary, and hypothalamic levels and does not fall neatly into one specific category. Despite the numerous potential sites of dysfunction, the evaluation is relatively straightforward and logical and requires tests and procedures with which all gynecologists should be quite familiar. With few exceptions, an accurate diagnosis can be confidently established in very little time and without great expense.

Differential Diagnosis of Amenorrhea

Although the list of potential causes of amenorrhea is long, the majority of cases relate to one of five conditions: pregnancy, PCOS, hypothalamic amenorrhea, hyperprolactinemia, and ovarian failure (Table 36.1). All of the remaining causes are relatively uncommon and only occasionally are encountered in a lifetime of clinical practice.

Genital Tract Abnormalities

Female genital tract development involves medial-caudal migration and midline fusion of the paired Müllerian (paramesonephric) ducts to form the tubes, uterus, cervix,

and upper vagina. Fusion of the downward migrating Müllerian duct system with the invaginating urogenital sinus forms the lower vagina and the introitus. Outflow tract abnormalities that result from failure of Müllerian duct development include vaginal or Müllerian agenesis and androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS), where the uterus is absent. Abnormalities caused by failure of fusion include imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septum, and cervical atresia. When the uterus is present but outflow obstruction is seen, the result is an accumulation of menstrual effluent above the level of obstruction (cryptomenorrhea). Asherman syndrome and cervical stenosis/obstruction are acquired conditions that cause secondary, not primary, amenorrhea. Asherman syndrome results from intrauterine adhesions that obstruct or obliterate the endometrial cavity as a consequence of inflammation (postpartum endometritis, retained products of conception) usually coupled with surgical trauma (curettage). Severe cervical stenosis, with complete outflow obstruction, is a rare complication of cervical conization procedures or other surgical treatments for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

and upper vagina. Fusion of the downward migrating Müllerian duct system with the invaginating urogenital sinus forms the lower vagina and the introitus. Outflow tract abnormalities that result from failure of Müllerian duct development include vaginal or Müllerian agenesis and androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS), where the uterus is absent. Abnormalities caused by failure of fusion include imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septum, and cervical atresia. When the uterus is present but outflow obstruction is seen, the result is an accumulation of menstrual effluent above the level of obstruction (cryptomenorrhea). Asherman syndrome and cervical stenosis/obstruction are acquired conditions that cause secondary, not primary, amenorrhea. Asherman syndrome results from intrauterine adhesions that obstruct or obliterate the endometrial cavity as a consequence of inflammation (postpartum endometritis, retained products of conception) usually coupled with surgical trauma (curettage). Severe cervical stenosis, with complete outflow obstruction, is a rare complication of cervical conization procedures or other surgical treatments for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

TABLE 36.1 Causes of Amenorrhea | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Ovarian Disorders

Ovarian failure occurs when no follicles capable of producing estradiol in response to pituitary gonadotropin stimulation remain. Follicular depletion may occur during embryonic life with no follicles remaining by infancy or early childhood, after puberty has begun but before menarche, or after menarche. Therefore, depending on when the available supply of ovarian follicles is functionally depleted, puberty may not occur, it may begin normally but stop before the first menses, or it may progress normally but menses stop prematurely before the anticipated age of menopause.

When the depletion of follicles occurs prior to puberty, it is termed gonadal dysgenesis. It is the most common cause of primary amenorrhea (approximately 30% to 40%) and results either from an absence of ovarian follicles or accelerated follicular depletion during embryogenesis or the first few years of life. The gonads of affected individuals contain only stroma and grossly appear as fibrous streaks. The most common form of gonadal dysgenesis is Turner syndrome, classically associated with a 45,X karyotype, but also with an assortment of other structural X chromosome abnormalities (deletions, ring, and isochromosomes). These X chromosome anomalies may be present in all or only in some of the cells of the body (mosaicism), depending on the stage of postzygotic, embryonic, development when the defect occurs. Although less common, individuals with gonadal dysgenesis may have a normal 46,XX or a 46,XY karyotype (Swyer syndrome) in all cells or in one or more cell lines in mosaic individuals (e.g., 45,X/46,XX; 45,X/46,XY). Most affected women have no significant secondary sexual development since there is an absence of hormone-producing ovarian follicles. A small percentage may go through puberty and have transient normal ovarian function depending on when the supply of ovarian follicles is depleted. Approximately 15% begin but do not complete pubertal development, and approximately 5% have sufficient follicles to complete puberty and begin spontaneous menstruation. It is not surprising, therefore, that spontaneous pregnancies rarely occur and are associated with a high risk of sex chromosome aneuploidy and spontaneous abortion.

Premature ovarian failure (POF) results in secondary amenorrhea after completion of puberty and before 40 years of age. Approximately 1% to 5% of women will develop POF. It is distinguished from gonadal dysgenesis on the basis of ovarian morphology and histology; instead of streak gonads, the ovaries in POF more closely resemble those of postmenopausal women. The karyotype in individuals with POF is most often normal (46,XX) but also may be mosaic (e.g., 45,X/46,XX). A specific cause for early follicular depletion in POF frequently cannot be determined and is presumed to result from inadequate germ cell migration during embryogenesis or accelerated atresia. POF is frequently associated with autoimmune disorders and in some cases (e.g., Addison disease) appears to result from an autoimmune lymphocytic oophoritis. Radiation and chemotherapy are two other important causes; the effects of both are dependent on dose and the age at time of treatment. Galactosemia is an autosomal recessive disorder of galactose metabolism caused by a deficiency of the enzyme galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase and another, albeit very rare, cause of POF. Affected women

have fewer primordial follicles presumably due to the cumulative toxicity of galactose metabolites on germ cell migration and survival.

have fewer primordial follicles presumably due to the cumulative toxicity of galactose metabolites on germ cell migration and survival.

Other rare disorders that may cause amenorrhea include 17α-hydroxylase deficiency, aromatase deficiency, and the gonadotropin-resistant ovary syndrome. Unlike ovarian failure, the ovaries of individuals with these disorders contain follicles and oocytes but do not produce estrogen. The enzyme 17α-hydroxylase mediates an early step in steroid hormone synthesis, without which progesterone cannot be converted to androgens and subsequently aromatized to estrogens. The enzyme aromatase mediates the conversion of androgenic precursors to estrogens; individuals with aromatase deficiency generally exhibit sexual ambiguity at birth, virilization at puberty, and multicystic ovaries. The gonadotropin-resistant ovary syndrome results from genetic mutations in the FSH or LH receptor or post-receptor signaling defects that prevent the ovaries from responding normally to gonadotropin stimulation. In this circumstance, ovarian follicles fail to develop beyond the early antral stage and therefore produce little estrogen.

Pituitary Disorders

Pituitary tumors may cause amenorrhea by directly compressing pituitary gonadotrophs or obstructing the portal venous network that delivers hypothalamic GnRH stimulation, resulting in decreased FSH and LH secretion. They also may cause inadequate or excessive production of other pituitary hormones. Directly or indirectly, these tumors may disrupt normal ovarian function and cause amenorrhea. Virtually all pituitary tumors are benign adenomas that may or may not be functional. Functional tumors may secrete prolactin, growth hormone (GH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). Primary malignant pituitary tumors are extremely rare.

Other uncommon pituitary disorders that may cause amenorrhea include the empty sella syndrome and Sheehan syndrome. The empty sella syndrome results from herniation of the arachnoid membrane, containing cerebrospinal fluid, into the sella turcica compressing the pituitary stalk and the pituitary gland. The sella contains spinal fluid but appears “empty” when viewed by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Sheehan syndrome results from acute infarction and necrosis of the pituitary gland. It is a rare complication of shock due to obstetric hemorrhage. Depending on the extent of pituitary damage, clinical consequences may be limited to disorders of reproductive function (failed lactation, amenorrhea) or multisystem failure due to panhypopituitarism.

Hypothalamic Disorders

The most common cause of amenorrhea results from absent or abnormal patterns of pulsatile hypothalamic GnRH secretion. This, in turn, leads to abnormal levels, or pulse patterns, of pituitary gonadotropin secretion. Both PCOS and hypothalamic amenorrhea that may result from emotional, nutritional, or physical stress have dysfunctional secretion of gonadotropins, but their pathophysiology and clinical presentations differ. Women with PCOS exhibit an increased frequency of pulsatile GnRH secretion, increased LH synthesis, hyperandrogenism, and impaired follicular maturation. In contrast, the inconsistent and generally lower frequency of pulsatile GnRH secretion in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea results in inadequate pituitary gonadotropin release, which is a failure to stimulate or sustain progressive follicular development.

Occasionally, a hypothalamic tumor (craniopharyngioma, meningioma, hamartoma, chordoma) may distort the tuberoinfundibular tract (pituitary stalk) with its portal venous network, interfering with effective delivery of GnRH, resulting in decreased pituitary FSH and LH secretion. Alternatively, interference with hypothalamic dopamine delivery to pituitary lactotrophs releases these cells from tonic inhibition, resulting in hyperprolactinemia. Hypothalamic tumors, therefore, may result in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and amenorrhea. In other rare instances, GnRH deficiency may be congenital as well. Kallmann syndrome results from a defect in the Kalig-1 gene and is associated with midline craniofacial defects and/or anosmia. Failure of olfactory and GnRH neuronal migration during embryogenesis results in primary amenorrhea and sexual infantilism.

Evaluation of Amenorrhea

A detailed medical history and physical examination are always important. In the patient with amenorrhea, elements of particular interest include growth and secondary sexual development (breast and pubic hair); menstrual history (if any); previous surgery or trauma to the pelvis or central nervous system (CNS); family history of hereditary disorders; evidence of physical, psychological or emotional stress; and symptoms and signs of hirsutism or galactorrhea as well as reproductive tract anatomy.

Medical History

In general, menarche should occur within 2 to 3 years after the initiation of pubertal development. In most young girls (approximately 80%), the first sign of puberty is an acceleration of growth, followed by breast budding (thelarche) and the appearance of pubic hair (adrenarche). In the remainder, adrenarche precedes thelarche, but the two events typically are closely linked in temporal appearance. Consequently, menarche should be expected as early as age 10 (when puberty begins at age 8) and rarely later than age 16 (when puberty initiates at age 13). Importantly, in the United States, the mean ages for thelarche, adrenarche,

and menarche in black girls are 6 to 12 months earlier than in white girls. Evaluation is indicated when secondary sexual development fails to begin by age 14 or fails to progress at a normal pace. Once menstrual cycles have been established, amenorrhea for an interval equivalent to three previous cycles, or 6 months, should also provoke an evaluation.

and menarche in black girls are 6 to 12 months earlier than in white girls. Evaluation is indicated when secondary sexual development fails to begin by age 14 or fails to progress at a normal pace. Once menstrual cycles have been established, amenorrhea for an interval equivalent to three previous cycles, or 6 months, should also provoke an evaluation.

Questions relating to past medical history and lifestyle may identify a severe or chronic illness (diabetes, renal failure, inflammatory bowel disease); head trauma; or evidence of physical, psychologic, or emotional stress. Weight loss or gain and the frequency and intensity of exercise may be revealing. Headaches, seizures, vomiting, behavioral changes, or visual symptoms may suggest a CNS disorder. Vaginal dryness or hot flushes are evidence of estrogen deficiency and suggest either ovarian failure or profound pituitary–hypothalamic dysfunction. Progressive hirsutism or virilization is evidence of hyperandrogenism that may result from PCOS, nonclassic (late-onset) congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), or an androgen-producing tumor of the ovary or adrenal gland; galactorrhea suggests hyperprolactinemia. An obstructed genital tract may present with cyclic pelvic pain or urinary complaints. Developmental anomalies include imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septum, and cervical atresia. A previous inguinal hernia repair or curettage suggests the possibility of a developmental anomaly or damage to the reproductive tract. Finally, the timing and duration of any treatment with progestational agents (oral contraceptive pills [OCPs], depot medroxyprogesterone acetate), GnRH agonists, or other medications (phenothiazines, reserpine derivatives, amphetamines, opiates, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, dopamine antagonists) or drugs (opiates) may provide important diagnostic clues.

Physical Examination

Body habitus often provides important clinical information in the evaluation of amenorrhea. Height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) should be recorded. Short stature (<60 inches) is a hallmark of gonadal dysgenesis. Lack of secondary sexual characteristics, webbing of the neck, low set ears and posterior hairline, widely spaced nipples, short fourth metacarpals or metatarsals, and a wide carrying angle of the arms (cubitus valgus) are among the classical stigmata of Turner syndrome. Low body weight and poor dentition are frequently associated with hypothalamic amenorrhea resulting from poor nutrition (eating disorders); bulimia; or physical, psychologic, or emotional stress. Conversely, obesity, or an increased waist-to-hip ratio (>0.85), is frequently associated with insulin resistance and hyperandrogenic chronic anovulation.

Examination of the skin may reveal a soft, moist texture as seen in hyperthyroidism; a rapid pulse and classic eye signs (exophthalmos, lid lag), a fine tremor, and hyperreflexia may provide further evidence to suggest a diagnosis of Graves disease. Hypothyroidism, on the other hand, should be considered when dry and thick skin, bradycardia, blunted reflexes, and thinning of the hair are identified. Orange discoloration of the skin, in the absence of scleral icterus, may result from hypercarotinemia associated with excessive ingestion of low-calorie, carotene-containing fruits and vegetables in dieting women. Acanthosis nigricans—velvety hyperpigmented skin most commonly observed at the nape of the neck, in the axillae, and beneath the breasts—strongly suggests severe insulin resistance and the possibility of Type II diabetes. Acne and hirsutism are indications of hyperandrogenism often associated with chronic anovulation (PCOS), nonclassic CAH, or ingestion of androgenic anabolic steroids. When accompanied by any sign of frank virilization (deepening of the voice, frontotemporal balding, decrease in breast size, increase in muscle mass, or clitoromegaly), the possibility of ovarian hyperthecosis or an ovarian or adrenal androgen-secreting neoplasm must be considered, especially if the temporal appearance of the symptoms is rapid.

Breast development, as assessed by Tanner staging, is a reliable indicator of estrogen production or exposure to exogenous estrogens. Arrested breast development suggests a disruption of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis. When menarche has not followed adult breast development, a developmental anomaly of the reproductive tract should be considered as well. The breast examination should include gentle compression, beginning at the base and moving toward the nipple. Microscopic examination of any nipple secretions that demonstrate lipid droplets indicates hormone-sensitive galactorrhea and suggests hyperprolactinemia.

Abdominal examination may reveal a mass resulting from hematometra or an ovarian neoplasm. Growth of hair from the pubic symphysis to the infraumbilical region suggests hyperandrogenism. Abdominal striae raise the possibility of Cushing syndrome but much more often result from progressive obesity or previous pregnancy.

As noted previously, thelarche and adrenarche typically are closely linked events during puberty, and in general, breast development and growth of pubic hair progress in a predictable sequence and tempo. The Tanner stages of breast and pubic hair development, therefore, should be consistent. Absent, or scant growth of pubic hair, is a classic sign of AIS, particularly when breast development is asymmetrically advanced. Although examination of the vagina in sexually immature girls, or in those with a small hymeneal ring, is often difficult, whenever possible, a speculum examination should be performed, occasionally requiring anesthesia. A patent vagina and visible cervix excludes Müllerian/vaginal agenesis, AIS, and most obstructive causes of amenorrhea. In those girls with an absent or infantile vaginal orifice, rectal examination should be performed and may reveal a distended hematocolpos above the obstruction when the uterus is present and functional.

Diagnostic Evaluation

A careful history and physical examination will always narrow the range of diagnostic possibilities. Laboratory investigation and imaging should be focused on that differential diagnosis, and with few exceptions, a diagnosis can be quickly and easily established.

Abnormal Genital Tract Anatomy

A history of primary amenorrhea accompanied by an absent or blind vagina confirms a developmental anomaly of the genital outflow tract. The list of diagnostic possibilities is short and includes an imperforate hymen, a transverse vaginal septum, cervical atresia, Müllerian/vaginal agenesis, and AIS (Fig. 36.1). Because each of these disorders has unique features, they generally are not difficult to distinguish.

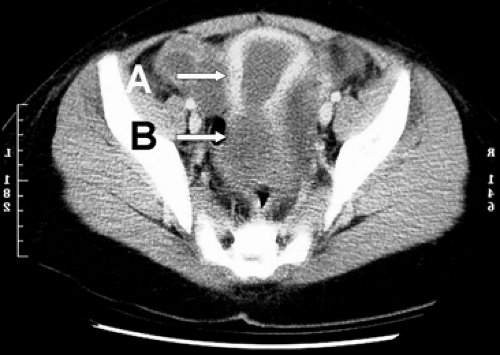

Patients with an imperforate hymen or transverse vaginal septum/cervical atresia typically present close to the anticipated time of menarche with cyclic perineal, pelvic, or abdominal pain and exhibit an otherwise normal pubertal sequence. With an imperforate hymen, examination reveals no obvious vaginal orifice but does reveal a thin, often bulging, blue perineal membrane and a mass, resulting from the accumulation of mucus and blood in the obstructed vagina. When a transverse vaginal septum or cervical atresia is present, examination reveals a normal vaginal orifice, a short blind vagina, and a pelvic mass above the level of obstruction (hematocolpos, hematometra, hematosalpinx). Differentiation of imperforate hymen and transverse vaginal septum/cervical atresia generally requires no laboratory investigation. A transabdominal or transperineal ultrasound examination will reveal the level and volume of sequestered menses; MRI provides greater anatomic detail and helps to define the anatomy of the anomaly (Fig. 36.2). In some instances, however, laparoscopy may be useful to more clearly define the anatomy. Patients with amenorrhea resulting from Müllerian agenesis usually are asymptomatic. They exhibit normal breast and pubic hair development but no vagina and no symptoms or signs of cryptomenorrhea because the uterus is absent. The diagnosis is usually self-evident from physical examination alone. Further evaluation to exclude skeletal and urinary tract anomalies is indicated. Approximately 12% to 15% of women with Müllerian agenesis have skeletal abnormalities (vertebral and distal extremity anomalies are most common), and one third or more have urinary tract anomalies (ectopic kidney, renal agenesis, horseshoe kidney, abnormal collecting system).

In girls in whom a uterus is present but who have not yet reached the age when menarche (and cryptomenorrhea) would be expected, imaging must be interpreted cautiously because imaging studies can be misleading when the reproductive organs are immature. Careful observation over time is preferable to repeated invasive investigations.

Normal breast development, absent or sparse growth of pubic hair, and a short blind vagina clearly suggest AIS. Although the chromosomal sex is male (46,XY), the phenotype is female. The testes are undescended, occasionally palpable in the inguinal canals (most commonly at the level of the external inguinal ring), and produce normal male levels of testosterone and Müllerian inhibitory hormone (MIH). Whereas end-organ insensitivity to androgen action, due to abnormalities of the androgen receptor, prevents normal masculinization of the external genitalia, MIH secretion is unaffected, resulting in inhibited

internal Müllerian development. Consequently, the external genitalia are phenotypically female, the uterus is absent, and the vagina is short and ends blindly, likely derived from the invaginating urogenital sinus. The diagnosis may be suspected when other family members (e.g., aunt, sister) are affected with this X-linked disorder. Incomplete penetrance may result in impeded but not absent androgen action with growth of more pubic hair than might be expected, but a serum testosterone concentration easily distinguishes AIS from Müllerian agenesis (normal range for a female) and a karyotype firmly establishes the diagnosis.

internal Müllerian development. Consequently, the external genitalia are phenotypically female, the uterus is absent, and the vagina is short and ends blindly, likely derived from the invaginating urogenital sinus. The diagnosis may be suspected when other family members (e.g., aunt, sister) are affected with this X-linked disorder. Incomplete penetrance may result in impeded but not absent androgen action with growth of more pubic hair than might be expected, but a serum testosterone concentration easily distinguishes AIS from Müllerian agenesis (normal range for a female) and a karyotype firmly establishes the diagnosis.

Cervical obstruction/stenosis and Asherman syndrome are abnormalities of genital tract anatomy, but physical examination of the genital tract most often is normal. When cervical stenosis causes symptoms, worsening dysmenorrhea or prolonged light staining or spotting after menses are the most common complaints; amenorrhea is a rare occurrence. In women with a history of previous conization or other cervical excisional or ablative therapy, uterine sounding may help to establish a diagnosis. Similarly, most women in whom previous infection or surgical trauma caused intrauterine synechiae present with dysmenorrhea, hypomenorrhea, subfertility, or recurrent early pregnancy loss, not amenorrhea. In women whose history clearly suggests the possibility of intrauterine adhesions, ultrasound and hysterosalpingography can reveal their location and extent, but hysteroscopy is the definitive method for diagnosis.

Normal Genital Tract Anatomy

When physical examination reveals normal genital tract anatomy, further evaluation is required to determine the cause of amenorrhea. The possibility of pregnancy should always be considered and excluded.

When breast growth is absent or inconsistent with age and associated with primary amenorrhea, the cause of delayed puberty should be determined. The vast majority of these cases have no pathology. In the remainder, evaluation may reveal thyroid disease, chronic illness (malabsorption, renal disease, eating disorders, inflammatory bowel disease), ovarian failure (e.g., gonadal dysgenesis), a pituitary disorder (tumor, empty sella syndrome, hyperprolactinemia), or a hypothalamic cause (Kallmann syndrome; physical, emotional, or psychologic stress; tumor). Wrist x-rays for bone age and a GnRH stimulation test are important components of the evaluation for delayed puberty in children and adolescents; the differential diagnosis and evaluation in adolescents and adults with primary or secondary amenorrhea are the same.

Thyroid Function Tests

Initial evaluation should include a measurement of serum TSH to detect both primary hypothyroidism (elevated TSH) and primary hyperthyroidism (low TSH). Either may rarely result in amenorrhea. Any abnormal value should be confirmed and accompanied by measurement of serum thyroxine (tetraiodothyronine [T4]) to better define the nature and extent of the thyroid disorder.

When TSH is elevated and the T4 concentration is normal, the diagnosis is subclinical hypothyroidism, best viewed as a compensated state wherein normal levels of T4 are maintained but with increased pituitary stimulation. On rare occasions, both TSH and T4 levels may be low, suggesting hypothyroidism of pituitary origin that will require additional evaluation to include hypothalamic/pituitary imaging (MRI) and careful assessment to determine whether other pituitary functions also are affected.

Prolactin

A serum prolactin determination is another component of the initial evaluation. If hyperprolactinemia occurs before menarche, it may result in delayed puberty and primary amenorrhea. After puberty, it is among the most common causes of secondary amenorrhea. Hyperprolactinemia inhibits pulsatile hypothalamic GnRH secretion, resulting in decreased levels of pituitary FSH and LH secretion. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism leads to oligo- or amenorrhea. Importantly, one cannot rely on galactorrhea to identify individuals with amenorrhea resulting from hyperprolactinemia. Only one third of hyperprolactinemic women will exhibit galactorrhea, probably because breast milk production requires several other hormones, including GH, T4, cortisol, insulin, and estrogen and progesterone. Serum prolactin determinations, therefore, should be obtained in all amenorrheic women.

Causes of hyperprolactinemia include:

Primary prolactin-secreting pituitary tumors

Other pituitary or hypothalamic tumors that may distort the hypophyseal portal circulation and prevent delivery of hypothalamic dopamine to maintain tonic inhibition of prolactin secretion.

Drugs that lower dopamine levels or inhibit dopamine action (amphetamines, benzodiazepines, butyrophenones, metoclopramide, methyldopa, opiates, phenothiazines, reserpine, and tricyclic antidepressants)

Breast or chest wall surgery, cervical spine lesions, or herpes zoster (all activate afferent sensory neural pathways and stimulate prolactin secretion)

Chronic estrogenized anovulation (PCOS), associated with modest elevations in prolactin caused by the effect of tonic estrogen on the galactotrophs but is not a cause for amenorrhea

Primary hypothyroidism (increased hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone stimulates prolactin secretion)

Pharmacologic estrogens (OCP)

Rare, nonpituitary sources (lung and renal tumors) or causes of decreased prolactin clearance (renal failure).

A careful history will eliminate many of these possibilities. When medications are the cause, prolactin

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree