American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Meyers JL, Dick DM: Genetic and environmental risk factors for adolescent-onset substance use disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2010 Jul;19(3):465–477 [PMID: 20682215].

Salomonsen-Sautel S et al: Medical marijuana use among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012 Jul;51(7):694–702 [PMID: 22721592].

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

The best current source of information on the prevalence of substance abuse among American adolescents is the Monitoring the Future study (2013), which tracks health-related behaviors in a sample of over 45,000 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the United States. This study probably understates the magnitude of the problem of substance abuse because it excludes high-risk adolescent groups—school dropouts, runaways, and those in the juvenile justice system. Substance abuse among American youth rose in the 1960s and 1970s, declined in the 1980s, peaked in the 1990s, and declined in the early 2000s. There was a decrease in substance use initiation between 1999 and 2008, but this trend reversed between 2008 and 2010 and substance use in adolescents continues to be a significant problem. The lifetime use of any illicit drug was 49% in 2012. The use of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs doubled from 8th to 12th grade. The use of alcohol and cigarettes more than tripled from adolescence (12–17 years) to young adulthood (18–25 years). Initiation of substance abuse is rare after age 20 years.

The Monitoring the Future survey and others show that alcohol is the most frequently abused substance in the United States. Experimentation with alcohol typically begins in or before middle school. It is more common among boys than girls. It is most common among whites, less common among Hispanics and Native Americans, and least common among blacks and Asians. Almost three-fourths (69%) of adolescents consume alcohol before graduating from high school. Approximately one-sixth (16%) of eighth graders and 54% of high school students report being drunk at least once in their life. Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States. First experiences with marijuana and the substances listed in Table 5–2 typically occur during middle or early high school. Marijuana use continued to rise in 2011 and leveled off in 2012 among all students. The lifetime prevalence of marijuana use among 12th graders in 2012 was 45.2% and daily use of marijuana continued to increase, with 1 in 16 (6.5%) high school seniors a daily or near daily user. Synthetic marijuana, often called spice and K-2, was scheduled by the Drug Enforcement Agency in 2011. Over 1 in 10 (11.4%) of 12 graders had used it in the past year. In the past decade, LSD, and methamphetamine use has decreased, while cocaine use has increased. Recently, ecstasy use has increased after a steady decline of several years. In the past 10 years, there has also been an increase in the recreational use of prescription medications and over-the-counter (OTC) cough and cold medications among adolescents. In one study, 1 in 10 high school seniors reported nonmedical use of prescription opioids, and almost half (45%) used opioids to “relieve physical symptoms” in the past year. Vicodin use decreased among 12th graders to 8% in 2010, but it remains one of the most widely used illicit drugs. Overall, the psychotherapeutic drugs (amphetamines, sedatives, tranquilizers, and narcotics other than heroin) make up a large part of the overall US drug problem. Medication used in the management of chronic pain, depression, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder can all be drugs of abuse.

Studies indicate that variations in the popularity of a substance of abuse are influenced by changes in the perceived risks and benefits of the substance among adolescent users. For example, the use of inhalants was rising until 2006, when both experience and educational efforts resulted in a perception of these substances as being “dangerous.” As the perception of danger decreases, old drugs may reappear in common use. This process is called “generational forgetting.” Currently, use of LSD, inhalants, and ecstasy all reflect the effects of generational forgetting. Legalization of marijuana in certain states in the United States may increase the scope and breath of the substance abuse problem. A recent study has shown an increase of medical marijuana use among adolescents in substance abuse programs.

Johnston LD et al: Monitoring the Future national results on drug use: 2012 overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2013.

Kuehn BM: Teen perceptions of marijuana risks shift: use of alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco declines. JAMA 2013 Feb 6; 309(5):429–430 [PMID: 23385247].

Salomonsen-Sautel S et al: Medical marijuana use among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012 Jul;51(7):694–702 [PMID: 22721592].

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011.

Young AM et al: Nonmedical use of prescription medications among adolescents in the United States: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health 2012 Jul;51(1):6–17 [PMID: 22727071].

Supplement Use & Abuse

Use of supplements or special diets to enhance athletic performance dates to antiquity. Today, many elite and casual athletes use ergogenic (performance-enhancing) supplements in an attempt to improve performance. The most popular products used by adolescents are anabolic-androgenic steroids, steroid hormone precursors, creatine, human growth hormone, diuretics, and protein supplements. Anabolic-androgenic steroids increase strength and lean body mass and lessen muscle breakdown. However, they are associated with side effects including acne, liver tumors, hypertension, premature closure of the epiphysis, ligamentous injury, and precocious puberty. In females, they can cause hirsutism, male pattern baldness, and virilization; in boys, they can cause gynecomastia and testicular atrophy. Creatine increases strength and improves performance but can cause dehydration, muscle cramps, and has potential for renal toxicity. Human growth hormone has no proven effects on performance although it decreases subcutaneous fat. Potential risks include coarsening of facial features and cardiovascular disease. Strength athletes (ie, weight lifters) use protein powders and shakes to enhance muscle repair and mass. The amount of protein consumed often greatly exceeds the recommended daily allowance for weight lifters and other resistance-training athletes (1.6–1.7 g/kg/d). Excess consumption of protein provides no added strength or muscle mass and can provoke renal failure in the presence of underlying renal dysfunction. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) cautions against the use of performance-enhancing substances.

As the use of supplements and herbs increases, it is increasingly important for pediatric care providers to be familiar with their common side effects. The Internet has become a source for information about and distribution of these products. The easy accessibility, perceived low risk, and low cost of these products significantly increase the likelihood that they will become substances of abuse by adolescents.

Castellanos D et al: Synthetic cannabinoid use: a case series of adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2011 Oct;49(4):347–349 [PMID: 21939863].

Harmer PA: Anabolic-androgenic steroid use among young male and female athletes: is the game to blame? Br J Sports Med 2010 Jan;44(1):26–31 [PMID: 19919946].

Howland J et al: Risks of energy drinks mixed with alcohol. JAMA 2013 Jan 16;309(3):245–246 [PMID: 23330172].

Marsolek MR et al: Inhalant abuse: monitoring trends by using poison control data, 1993–2008. Pediatrics 2010 May;125(5): 906–913 [PMID: 20403928].

McCool J et al: Do parents have any influence over how young people appraise tobacco images in the media? J Adolesc Health 2011 Feb;48(2):170 [PMID: 21257116].

Sepkowitz KA: Energy drinks and caffeine-related adverse effects. JAMA 2013 Jan 16;309(3):243–244 [PMID: 23330171].

Bath Salts

Since 2010, there has been an increase in the use of a newer drug of abuse called “bath salts.” These products, which are not related to hygienic products, are also known as Vanilla Sky or Ivory Wave. The main ingredient is 4-methylene-dioxypyrovalerone, a central nervous stimulant that acts by inhibiting norepinephrine-dopaminergic reuptake. The effects of these substances are similar to those of stimulants like PCP, ecstasy, and LSD (see Tables 5–1 and 5–2). Overdoses can potentially be severe and lethal. Their use increased rapidly in 2010, peaked in the first half of 2011, and declined by half in 2012. The recent decrease in use occurred due to efforts of drug enforcement agencies and media dissemination of messages about the dangers of bath salts, resulting in increased perception of risk. Additionally, they are now less easily available via the Internet. These substances cannot be detected by routine drug screen, which may complicate management in the emergency department. The 2012 Monitoring the Future survey found annual prevalence rate of use to be 1.3% among grade 12 adolescents.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Emergency department visits after use of a drug sold as “bath salts”—Michigan, November 13, 2010–March 31, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 May 20;60(19):624–627 [PMID: 21597456].

http://www.aapcc.org/alerts/bath-salts/ accessed from American Association of Poison Control Centers.

Ross EA et al: “Bath salts” intoxication. N Engl J Med 2011 Sep 8; 365(10):967–968 [PMID: 21899474].

Spiller HA et al: Clinical experience with and analytical confirmation of “bath salts” and “legal highs” (synthetic cathinones) in the United States. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011 Jul;49(6):499–505 [PMID: 21824061].

MORBIDITY DATA

Use and abuse of alcohol or other mood-altering substances in adolescents in the United States are tightly linked to adolescents’ leading causes of death, i.e., motor vehicle accidents, unintentional injury, homicide, and suicide. Substance abuse is also associated with physical and sexual abuse. Drug use and abuse contribute to other high-risk behaviors, such as unsafe sexual activity, unintended pregnancy, and sexually transmitted disease. Adolescents may also be involved with selling of drugs.

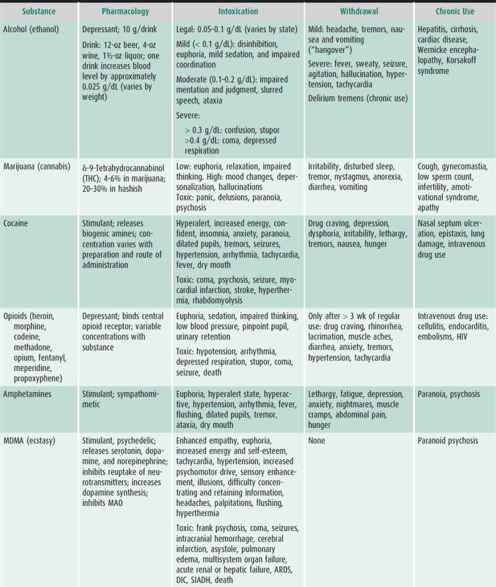

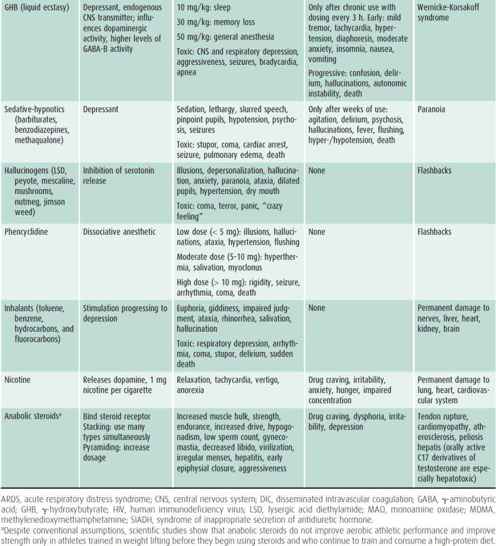

Risks associated with tobacco, alcohol, and cocaine are listed in Table 5–2. Less well known are the long- and short-term adolescent morbidities connected with the currently most popular illicit drugs, marijuana, and ecstasy. The active ingredient in marijuana, δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), transiently causes tachycardia, mild hypertension, and bronchodilation. Regular use can cause lung changes similar to those seen in tobacco smokers. Heavy use decreases fertility in both sexes and impairs immunocompetence. It is also associated with abnormalities of cognition, learning, coordination, and memory. It is possible that heavy marijuana use is the cause of the so-called amotivational syndrome, characterized by inattention to environmental stimuli and impaired goal-directed thinking and behavior. Analysis of confiscated marijuana recently has shown increasing THC concentration and adulteration with other substances.

The popularity and accessibility of ecstasy is again increasing among adolescents. Chronic use is associated with progressive decline of immediate and delayed memory, and with alterations in mood, sleep, and appetite that may be permanent. Even first-time users may develop frank psychosis indistinguishable from schizophrenia. Irreversible cardiomyopathy, noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, and pulmonary hypertension may occur with long-term use. Acute overdose can cause hyperthermia and multiorgan system failure.

Prenatal and environmental exposure to abused substances also carries health risks. Parental tobacco smoking is associated with low birth weight in newborns, sudden infant death syndrome, bronchiolitis, asthma, otitis media, and fire-related injuries. Maternal use of marijuana during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome. In-utero exposure to alcohol may produce fetal malformations, intrauterine growth restriction, and brain injury.

Bada HS et al: Protective factors can mitigate behavior problems after prenatal cocaine and other drug exposures. Pediatrics 2012 Dec;130(6):e1479-e1288 [PMID: 23184114].

Bailey JA: Addressing common risk and protective factors can prevent a wide range of adolescent risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health 2009 Aug;45(2):107–108 [PMID: 19628134].

Delcher C et al: Driving after drinking among young adults of different race/ethnicities in the United States: unique risk factors in early adolescence? J Adolesc Health 2013 May;52(5):584–591 [PMID: 23608720].

Frese W et al. Opioids: Nonmedical use and abuse in older children. Pediatr Rev 2011 Apr;32(4):e44-e52 [PMID: 21460089].

Grenard JL et al: Exposure to alcohol advertisements and teenage alcohol-related problems. Pediatrics 2013 Feb;131(2): e369–e379 [PMID: 23359585].

Herrick AL et al: Sex while intoxicated: a meta-analysis comparing heterosexual and sexual minority youth. J Adolesc Health 2011 Mar;48(3):306–309 [PMID: 21338904].

Hingson RW et al: Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics 2009;123:1477–1484 [PMID: 19482757].

McCabe SE et al: Medical misuse of controlled medications among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 Aug;165(8): 729–735 [PMID: 21810634].

Walton MA et al: Sexual risk behaviors among teens at an urban emergency department: relationship with violent behaviors and substance use. J Adolesc Health 2011 Mar;48(3):303–305 [PMID: 21338903].

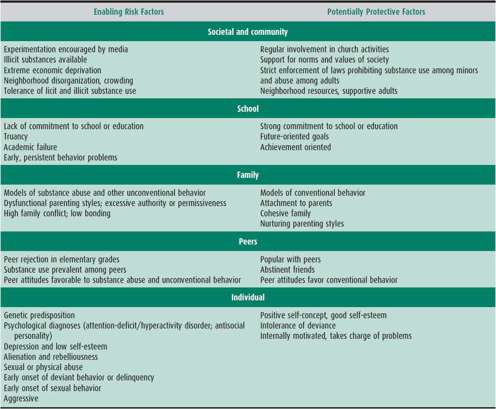

PREDICTING THE PROGRESSION FROM USE TO ABUSE

Initially, most adolescents use mood-altering substances intermittently or experimentally. The challenge to pediatric healthcare providers is to recognize warning signs, identify potential abusers early, and intervene in an effective fashion before acute or chronic use produces morbidity. The prediction of progression from use to abuse is best viewed within the biopsychosocial model. Substance abuse is a symptom of personal and social maladjustment as often as it is a cause. Because there is a direct relationship between the number of risk factors listed in Table 5–3 and the frequency of substance abuse, a combination of risk factors is the best indicator of risk. Even so, most teenagers with multiple risk characteristics never progress to substance abuse. It is unclear why only a minority of young people exhibiting the high-risk characteristics listed in Table 5–3 go on to abuse substances, but presumably the protective factors listed in Table 5–3 give most adolescents the resilience to cope with stress in more socially adaptive ways. Being aware of the risk domains in Table 5–3 will help physicians identify youngsters most apt to need counseling about substance abuse.

Table 5–3. Factors that influence the progression from substance use to substance abuse.

Chartier KG et al: Development and vulnerability factors in adolescent alcohol use. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2010 Jul;19(3):493–504 [PMID: 20682217].

McCoy SI et al: A trajectory analysis of alcohol and marijuana use among Latino adolescents in San Francisco, California. J Adolesc Health 2010 Dec;47(6):564–574 [PMID: 21094433].

Meyers JL et al: Genetic and environmental risk factors for adolescent-onset substance use disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2010 Jul;19(3):465–477 [PMID: 20682215].

Prado G et al: What accounts for differences in substance use among U.S.-born and immigrant Hispanic adolescents? Results from a longitudinal prospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health 2009 Aug;45(2):118–125 [PMID: 19628137].

Strachman A et al: Early adolescent alcohol use and sexual experience by emerging adulthood: a 10-year longitudinal investigation. J Adolesc Health 2009 Nov;45(5):478–482 [PMID: 19837354].

Sutfin EL et al: Protective behaviors and high-risk drinking among entering college freshmen. Am J Health Behav 2009;33:610–619 [PMID: 19296751].

Tobler AL et al: Trajectories or parental monitoring and communication and effects on drug use among urban young adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2010 Jun;46(6):560–568 [PMID: 20472213].

EVALUATION OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Office Screening

The AAP Committee on Substance Abuse recommends that pediatricians include discussions of substance abuse as part of their anticipatory care. This should include screening for substance abuse with parents at the first prenatal visit. Given the high incidence of substance abuse and the subtlety of its early signs and symptoms, a general psychosocial assessment is the best way to screen for substance abuse among adolescents. The universal screening approach outlined in the American Medical Association (AMA) Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS) is a good guide for routine screening and diagnosis. Interviewing and counseling techniques and methods for taking a psychosocial history are discussed in Chapter 4. In an atmosphere of trust and confidentiality, physicians should ask routine screening questions of all patients and be alert for addictive diseases, recognizing the high level of denial often present in addicted patients. Clues to possible substance abuse include truancy, failing grades, problems with interpersonal relationships, delinquency, depressive affect, chronic fatigue, recurrent abdominal pain, chest pains or palpitations, headache, chronic cough, persistent nasal discharge, and recurrent complaints of sore throat. Substance abuse should be included in the differential diagnosis of all behavioral, family, psychosocial, and medical problems. A family history of drug addiction or abuse should raise the level of concern about drug abuse in the pediatric patient. Possession of promotional products such as T-shirts and caps with cigarette or alcohol logos should also be a red flag because teenagers who own these items are more likely to use the products they advertise. Pediatricians seeing patients in emergency departments, trauma units, or prison should have an especially high index of suspicion.

In the primary care setting, insufficient time and lack of training are the greatest barriers to screening adolescents for substance abuse. Brief questionnaires can be used if time does not allow for more detailed investigation. A screening instrument that has been rigorously studied in primary care settings is the CAGE questionnaire. CAGE is a mnemonic derived from the first four questions that asks the patient questions regarding their substance use. These are their need to reduce it, annoyance if asked about it, feeling guilty about the use, and the need of the drug/alcohol as an eye opener. A score of 2 or more is highly suggestive of substance abuse. Although constructed as a screening tool for alcohol abuse in adults, the CAGE questionnaire can be adapted to elicit information about use of other mood-altering substances by pediatric patients and their close contacts (eg, parents and older siblings). Clinicians may find it helpful to use such questionnaires to stimulate discussion of the patient’s self-perception of his or her substance use. For example, if an adolescent admits to a previous attempt to cut down on drinking, this provides an opportunity to inquire about events that may have led to the attempt. Unfortunately, despite guidance to screen adolescents for substance abuse, recent studies demonstrate that clinicians do not regularly ask/advise adolescents about substance use.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree