Nwanneka N Sargant, Lee Hudson, Janet McDonagh • Know about the epidemiology of adolescent medicine • Know about the physical and psychological changes during adolescence • Be aware of chronic pain in adolescence and its management • Understand the main issues relating to sexual health • Be aware of the issues around the transition of young people to adult services

Adolescent medicine

Adolescent healthcare has come a long way since Amelia E Gates, a San Francisco physician, established the first dedicated adolescent clinic at Stanford in 1918. However, a century later, the healthcare provision for young people is still in major need of improvement (see Chief Medical Officer’s report, 2012). Although it has been included as a separate chapter, there are important strands of adolescent medicine woven through many of the other chapters.

What is adolescence?

Adolescence is the transition from childhood to adulthood. It is a complex sequence of profound biological, psychological and sociological changes, which can have a significant impact on a young person’s health and behaviour. Perhaps because of their proximity to adulthood, it is frequently forgotten that young people are at a genuine developmental stage with specific needs just like children at other ages. They are not yet adults, but neither are they children. This needs to be considered when trying to understand their behaviours and specific health requirements. It is facilitated by adopting a life-course approach to healthcare where adolescence is seen as integral in the continuum between childhood and adulthood.

Defining adolescence according to specific ages is problematic because, as in other aspects of child development, there is much variation in both timing and tempo between individuals (Box 32.1). Throughout this chapter, the WHO definition of adolescence of 10–19 years will be used. The start of adolescence reflects the onset of puberty and begins earlier in girls with breast budding, normally at 10–11 years. Defining an end to adolescence is more complex, although the provision in law of minimum age limits is implicit of society’s expectation that sufficient neuro-developmental competencies for important adult responsibilities (e.g. voting) will have been acquired by 18 years of age. In legal terms, young people under the age of 18 in the UK are still provided for under the Children Act of 2004, with parental responsibility taking prominence. However, concepts of competence have changed in recent years to allow young people under the age of 18 years to be able to give consent for their own treatment (see Chapter 35, Ethics) and neuroscience research suggests that adolescent brain development continues well into the third decade.

Cultural aspects of a young person’s life are also important in defining a transition from childhood to adulthood. Commencement of adult social roles, such as employment and childbirth, can occur during adolescence. In high-income countries, it is interesting to reflect on the widening gap which exists between childhood and key early adult life events, which have traditionally represented autonomy and independence (such as marriage, first child and leaving the family home). This has mostly been driven by socio-economic changes, and in the past 30 years, a significant popular cultural movement has also developed specific to adolescence, with commercial recognition of the influence the adolescent age group has. The rise of this cultural movement has been associated with both positive and negative effects on adolescents.

Epidemiology

There have never been as many young people in the world as there are now, with a quarter of the global population represented by 10–24-year-olds. In the UK, young people represent 12.5% of the population, a similar proportion to the over 70-year-olds and the 0–9-year-olds. A fifth of adolescents in the UK are from ethnic minorities.

Lifelong health behaviours develop during adolescence and therefore it is important to promote healthy lifestyles during this life stage in order to influence long-term health outcomes. Health promotion is discussed in detail later in this chapter. A significant proportion of the 11–18 year age group are overweight or obese (31% of boys and 37% of girls), whilst much smaller proportions of young people meet recommended levels of physical activity, with girls being worse than boys. It is recognized that half of all lifetime cases of psychiatric disorders manifest by age 14 and three quarters by age 24. Studies have shown that approximately 13% of boys and 10% of girls aged 11–15 years have mental health problems, with conduct disorders being most common in boys and emotional difficulties in girls. Mental health is covered in Chapter 24, Child and adolescent mental health, and substance use and sexual activity will be discussed later in this chapter.

Long-term conditions or disabilities affect a significant minority of adolescents. One study in England found that one in seven young people aged 11–15 reported having been diagnosed with a long-term medical illness or disability. Furthermore, two thirds of those with a long-term condition were taking medication and one third reported that their condition affected their engagement with school. Long-term pain and chronic health conditions were the most common forms of impairment experienced by older adolescents and young adults. Advances in medical care have resulted in increasing numbers of these young people with chronic illnesses (such as cystic fibrosis, congenital heart disease, inherited metabolic disease, cancer and cerebral palsy) surviving into adulthood, whereas previously they died in childhood. These survival rates have major implications for the development of transitional care provision as young people move from child- to adult-centered health services.

A number of long-term conditions are characterized by a peak age of onset in adolescence and young adulthood. These include type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus, eating disorders and other mental health disorders. The number of hospital admissions in England among 10–19 year olds for diabetes, epilepsy and asthma has been increasing over the last decade. These increased admission rates raise questions about the standards of care for young people with long-term conditions, particularly around the transfer from paediatric to adult care.

Determinants of adolescent health

Health is affected by a wide range of social, economic and environmental factors irrespective of the age of the individual. In the UK in 2010–2011, more than a fifth (22%) of young people aged 11–15 years were living in families with the lowest levels of income and at increased risk of ill-health. Adolescence is a key period for establishing both health promoting as well as health risk behaviours, which in turn are influenced by family, peers, local community and education. Since such behaviours track into adulthood, social determinants of adolescent health are crucial to the health and economic development of the society they live in.

The strongest determinants of the health of adolescents worldwide are national wealth, income inequality and access to education, closely followed by family, schools and peers. Improving adolescent health will therefore need to consider these issues in addition to improvements in access to education and employment for young people and the reduction of risk of road traffic accidents. In the UK, although participation in further and higher education has increased in recent years, youth unemployment has also risen and was 14% in 2015, almost three times the overall rate. The health of these adolescents and young adults who are not in employment, education or training is of increasing concern.

Mortality in adolescence

Adolescence is often considered a healthy stage of life, but there are deaths among 10–24 year olds which are often preventable. The main causes of death in this age group are external, namely traffic accidents, violence-related or self-harm, followed by neoplasms, diseases of the nervous system (e.g. muscular dystrophy) and congenital and chromosomal abnormalities.

Although overall trends have been decreasing since 2003, death in the 15–19 and 20–24-year-old age groups is more common than in younger children if infants are excluded. In particular disease groups, the reduction in mortality seen in other age groups has not occurred. For example, adolescent-onset cancer mortality is unchanged compared to the improved rates in child and adult-onset disease. Rejection-related death following cardiac transplant is highest in the adolescent and young adult age groups. The explanation for these differences is not yet known, but intrinsic factors, such as the impact of aspects of adolescent development including puberty and brain development, as well as extrinsic factors, such as health service provision, are likely to be contributing factors.

Resilience

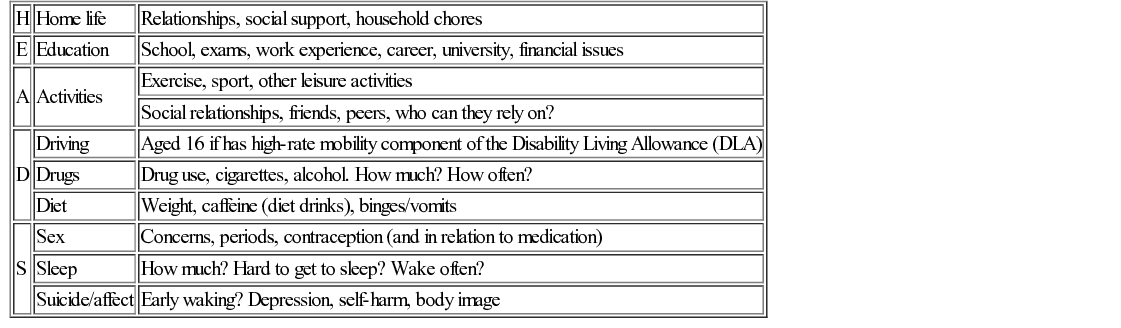

The other core principle underpinning adolescent medicine is that of resilience. Resilience refers to the ability to rebound from adversity and be flexible and adaptable, with resilient individuals even managing to thrive against what appears to be overwhelming odds. When taking a history from a young person, it is important to consider resilience as well as risk. What talents, resources and skills does this individual young person possess which will protect his health and emotional well-being? The HEADSSS psychosocial screening tool is useful in this regard (Table 32.2).

Specifics of adolescent development

Physical development

The physical hallmark of development in adolescence is puberty. This has been discussed in detail in Chapter 12, Growth and puberty. In girls, the growth spurt occurs before the onset of menses, whereas in boys, the growth spurt occurs later. In certain conditions, this has significant consequences. The peak onset of eating disorders in males tends to occur before or during the growth spurt, whereas, in females, onset is typically after the growth spurt. Risk of growth stunting following eating disorders is therefore higher in males.

Rapid growth seems to increase the risk of some symptoms. Adolescent back pain is more common in those with increased truncal length. Back pain occurs commonly in adolescents, affecting up to 50% of children by age 18–20 years. Whilst an underlying cause is not identified in most children, it is important to consider spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis, particularly in active and rapidly growing adolescents.

Spondylolysis is a fracture of the pars interarticularis or pedicle. This is most likely to affect the lower lumbar vertebrae and be caused by an injury or repetitive activity. The activities that most likely cause spondylolysis include extension (bending backwards) and rotation. Spondylolysis can also cause back pain in children, especially those that are active in sports. It may happen in 4–5% of children by the age of six, and up to 6% of adults. Spondylolysis is three times more common in boys than girls. Growth spurts and involvement in contact sports may explain this observed sex difference. Spondylolysis may cause pain in a particular spot in the low back and spasm of the muscles along the spine. Often it will cause pain into the buttocks or thighs.

Initially, plain spine X-rays may not show a fracture and MRI scanning of the spine may be required to confirm the diagnosis. It is likely to heal with a change in activity, rest, and avoiding hyperextension and rotation. Bracing may be helpful if symptoms do not improve. If symptoms do not improve, spondylolisthesis, the forward displacement of one vertebra on another, may be responsible.

Likewise, premature fusion of epiphyses, which may also occur as a consequence of inflammatory arthritis leading to asymmetrical growth, should be considered during examination of affected young people. Distribution of drugs can be affected by the changes in body size and composition characteristic of puberty. The increase in lean body mass during adolescence is usually greater in boys than girls, resulting in girls having relatively more body fat than boys in late puberty; this has implications for the volume of distribution of some drugs.

Pubertal assessment (including the identification of abnormal pubertal timing) is important in all clinical interactions with young people, particularly with respect to the impact of puberty on psychosocial development. The use of pubertal self-assessment tools are useful in the clinical consultation and provide a means of facilitating discussions in this area with individual young people.

Other aspects of adolescent physical growth include bone mass development, with 40% of adult bone mass being accrued during this period. This is coupled with a reduction in observed vitamin D levels, which can result in suboptimal bone mineralization, an increased fracture risk and more commonly bone pain.

The proportion of children with vitamin D insufficiency increases with age. In the UK, 11–16% of adolescents (aged 11–18 years) have vitamin D deficiency compared to less than 7% of children aged between 1.5 and 10 years of age. This has led to some countries, like the USA, to recommend routine vitamin D supplementation for all adolescents.

Psychological development

Development of a perception of one’s own body, such as how it looks, feels and moves (body image), is associated with the rapid changes in the physical body that come with puberty. Body image is shaped by perception, emotions, and physical sensations and can vary in response to mood, physical experience and environment. There are intrinsic influences of body image (self-esteem and self-evaluation) as well as extrinsic influences (evaluation by others, cultural messages and societal standards). Addressing body image, particularly in the peri-pubertal phase, is important.

The other key features of psychological development in adolescence were first described in 1929 by Piaget and later by Erikson in 1950. Piaget identified that during adolescence there is a shift in cognitive style from the concrete processes of childhood to more abstract ways of thinking, allowing problem-solving using hypotheses and propositions. Erikson then identified search and acquisition of identity as being characteristic of development in adolescence. Both abstract thought and independent identity are important skills to acquire for successful function as an adult. These are important concepts for doctors working with young people, as a better understanding of the cognitive level of individual young people will inform the consultation and help to understand the impact of current interventions and exposures upon future health outcomes. For example, the use of immediate motivators are preferable with concrete thinkers whereas future motivators are fine to use with abstract thinkers. The different perceptions of young people undergoing similar problems is important to consider in consultation and is exemplified in the case history below. Finally, one must recognize that there may be delay in the development of abstract thought in adolescents with chronic conditions or regression to concrete thought during times of stress.