Figure 4–1. Interrelation of high-risk adolescent behavior.

Figure 4–1. Interrelation of high-risk adolescent behavior.

Early identification of the teenager at risk for these problems is important in preventing immediate complications and future associated morbidities. Early indicators for problems related to depression include

1. Decline in school performance

2. Excessive school absences or cutting class

3. Frequent or persistent psychosomatic complaints

4. Changes in sleeping or eating habits

5. Difficulty in concentrating or persistent boredom

6. Signs or symptoms of depression, extreme stress, or anxiety

7. Withdrawal from friends or family or change to a new group of friends

8. Severe violent or rebellious behavior or radical personality change

9. Conflict with parents

10. Sexual acting-out

11. Conflicts with the law

12. Suicidal thoughts or preoccupation with themes of death

13. Drug and alcohol abuse

14. Running away from home

Baker SP, Chen L, Li G: Nationwide Review of Graduated Driver Licensing. Washington, DC: AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety; 2007. http://www.aaafoundation.org/pdf/NationwideReviewOfGDL.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

D’Angelo LJ, Halpern-Felsher BL et al: Adolescents and driving: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. J Adolesc Health 2010;47(2):212–214 [PMID: 20638018].

Mulye TP et al: Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2009;45(1):8–24 [PMID: 19541245].

Teen Drivers: Fact Sheet: http://www.cdc.gov/motorvehiclesafety/teen_drivers/teendrivers_factsheet.html.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau: Child Health USA 2012. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013.

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS): http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm.

DELIVERY OF HEALTH SERVICES

How, where, why, and when adolescents seek health care depends on ability to pay, distance to healthcare facilities, availability of transportation, accessibility of services, time away from school, and privacy. Many common teenage health issues, such as unintended pregnancy, contraception, STI, substance abuse, depression, and other emotional problems have moral, ethical, and legal implications. Teenagers are often reluctant to confide in their parents for fear of punishment or disapproval. Recognizing this reality, healthcare providers have established specialized programs such as teenage family planning clinics, drop-in centers, STI clinics, hotlines, and adolescent clinics. Establishing a trusting and confidential relationship with adolescents is basic to meeting their healthcare needs. Patients who sense that the physician will inform their parents about a confidential problem may lie or fail to disclose information essential for proper diagnosis and treatment.

GUIDELINES FOR ADOLESCENT PREVENTIVE SERVICES

The American Medical Association guidelines for adolescent preventive services and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents cover health screening and guidance, immunization, and healthcare delivery. The goals of these guidelines are (1) to deter adolescents from participating in behaviors that jeopardize health; (2) to detect physical, emotional, and behavioral problems early and intervene promptly; (3) to reinforce and encourage behaviors that promote healthful living; and (4) to provide immunization against infectious diseases. The guidelines recommend that adolescents between ages 11 and 21 years have annual routine health visits. Health services should be developmentally appropriate and culturally sensitive. Confidentiality between patient and physician should be ensured.

RELATING TO THE ADOLESCENT PATIENT

Adolescence is one of the physically healthiest periods in life. The challenge of caring for most adolescents lies not in managing complex organic disease, but in accommodating the cognitive, emotional, and psychosocial changes that influence health behavior. The physician’s initial approach to the adolescent may determine the success or failure of the visit. The physician should behave simply and honestly, without an authoritarian or excessively professional manner. Because the self-esteem of many young adolescents is fragile, the physician must be careful not to overpower and intimidate the patient. To establish a comfortable and trusting relationship, the physician should strive to present the image of an ordinary person who has special training and skills.

Because the onset and termination of puberty vary from child to child, chronologic age may be a poor indicator of physical, physiologic, and emotional maturity. In communicating with an adolescent, the physician must be sensitive to the adolescent’s developmental level, recognizing that outward appearance and chronologic age may not be an accurate reflection of cognitive development.

Working with teenagers can be emotionally draining. Adolescents have a unique ability to identify hidden emotional vulnerabilities. The physician who has a personal need to control patients or foster dependency may be disappointed in caring for teenagers. Because teenagers are consumed with their own emotional needs, they rarely provide the physician with ego rewards as do younger or older patients.

The physician should be sensitive to the issue of counter-transference—the emotional reaction elicited in the physician by the adolescent. How the physician relates to the adolescent patient often depends on the physician’s personal characteristics. This is especially true of physicians who treat families that are experiencing parent-adolescent conflicts. It is common for young physicians to overidentify with the teenage patient and for older physicians to see the conflict from the parents’ perspective.

Overidentification with parents is readily sensed by the teenager, who is likely to view the physician as just another authority figure who cannot understand the problems of being a teenager. Assuming a parental-authoritarian role may jeopardize the establishment of a working relationship with the patient. In the case of the young physician, overidentification with the teenager may cause the parents to become defensive about their parenting role and to discount the physician’s experience and ability.

THE SETTING

Adolescents respond positively to settings and services that communicate sensitivity to their age. A pediatric waiting room with toddlers’ toys and infant-sized examination tables makes adolescent patients feel they have outgrown the practice. A waiting room filled with geriatric or pregnant patients can also make a teenager feel out of place.

CONFIDENTIALITY

It is not uncommon that a teenage patient is brought to the office against his or her wishes, especially for evaluations of drug and alcohol use, parent-child conflict, school failure, depression, or a suspected eating disorder. Even in cases of acute physical illness, the adolescent may feel anxiety about having a physical examination. If future visits are to be successful, the physician must spend time on the first visit to foster a sense of trust and comfort.

It is helpful at the beginning of the visit to talk with the adolescent and the parents about what to expect. The physician should address the issue of confidentiality, telling the parents that two meetings—one with the teenager alone and one with only the parents—will take place. Adequate time must be spent with both patient and parents or important information may be missed. At the beginning of the interview with the patient, it is useful to say, “I am likely to ask you some personal questions. This is not because I am trying to pry into your personal affairs, but because these questions may be important to your health. I want to assure you that what we talk about is confidential, just between the two of us. If there is something I feel we should discuss with your parents, I will ask your permission first unless I feel it is life-threatening.”

THE STRUCTURE OF THE VISIT

Caring for adolescents is time-intensive. In many adolescent practices, a 40%–50% no-show rate is not unusual. The stated chief complaint often conceals the patient’s real concern. For example, a 15-year-old girl may say she has a sore throat but actually may be worried about being pregnant.

By age 11 or 12 years, patients should be seen alone. This gives them an opportunity to ask questions they may be embarrassed to ask in front of a parent. Because of the physical changes that take place in early puberty, some adolescents are too self-conscious to undress in front of a parent. If an adolescent comes in willingly, for an acute illness or for a routine physical examination, it may be helpful to meet with the adolescent and parent together to obtain the history. For angry adolescents brought in against their will, it is useful to meet with the parents and patient for 3–5 minutes to allow the parents to describe the conflict and voice their concerns. The adolescent should then be seen alone. This approach conveys that the physician is primarily interested in the adolescent patient, yet gives the physician an opportunity to acknowledge parental concerns.

The Interview

The first few minutes may determine whether or not a trusting relationship can be established. A few minutes just getting to know the patient is time well spent. For example, immediately asking “Do you smoke marijuana?” when a teenager is brought in for suspected marijuana use confirms the adolescent’s negative preconceptions about the physician and the purpose of the visit. It is preferable to spend a few minutes asking nonthreatening questions, such as “Tell me a little bit about yourself so I can get to know you,” “What do you like to do most?” “Least?” and “What are your friends like?” Neutral questions help defuse some of the patient’s anger and anxiety. Toward the end of the interview, the physician can ask more directed questions about psychosocial concerns.

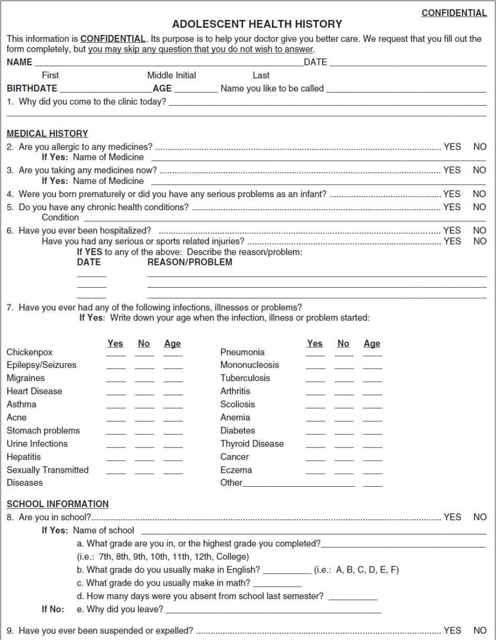

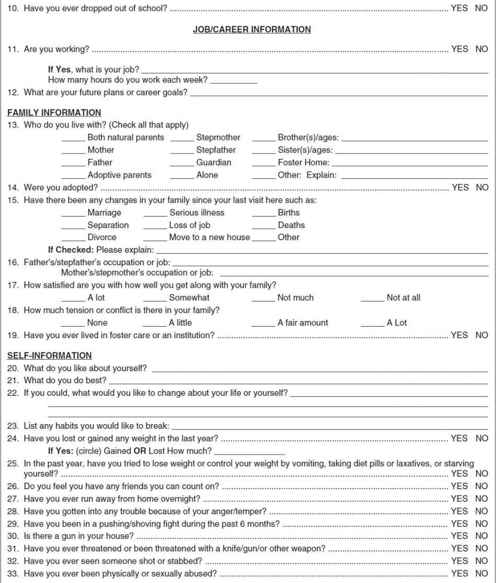

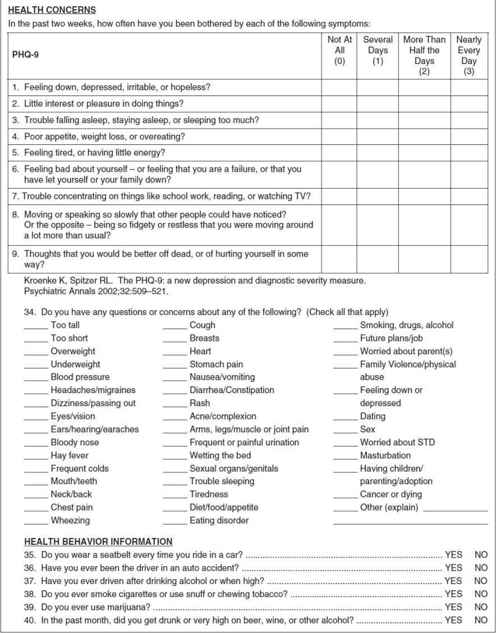

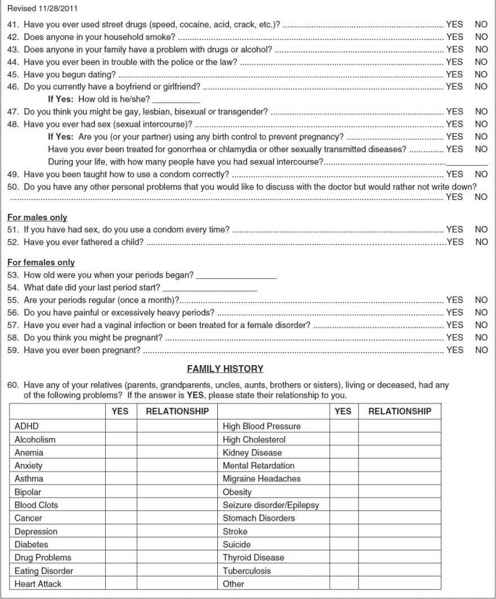

Medical history questionnaires for the patient and the parents are useful in collecting historical data (Figure 4–2). The history should include an assessment of progress with psychodevelopmental tasks and of behaviors potentially detrimental to health. The review of systems should include questions about the following:

1. Nutrition: Number and balance of meals; calcium, iron, fiber, and cholesterol intake; body image.

2. Sleep: Number of hours, problems with insomnia or frequent waking.

3. Seat belt or helmet: Regularity of use.

4. Self-care: Knowledge of testicular or breast self-examination, dental hygiene, and exercise.

5. Family relationships: Parents, siblings, relatives.

6. Peers: Best friend, involvement in group activities, gangs, boyfriends, girlfriends.

7. School: Attendance, grades, activities.

8. Educational and vocational interests: College, career, short-term and long-term vocational plans.

9. Tobacco: Use of cigarettes and chewing and smokeless tobacco.

10. Substance abuse: Frequency, extent, and history of alcohol and drug use.

11. Sexuality: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, pregnancies, history of STI, number of sexual partners, risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

12. Emotional health: Signs of depression, anxiety, and excessive stress.

The physician’s personal attention and interest is likely to be a new experience for the teenager, who has probably received medical care only through a parent. The teenager should leave the visit with a sense of having a personal physician.

Physical Examination

During early adolescence, teenagers may be shy and modest, especially with a physician of the opposite sex. The examiner should address this concern directly, because it can be allayed by acknowledging the uneasiness verbally and by explaining the purpose of the examination. For example, “Many boys that I see who are your age are embarrassed to have their penis and testes examined. This is an important part of the examination for a couple of reasons. First, I want to make sure that there aren’t any physical problems, and second, it helps me determine if your development is proceeding normally.” This also introduces the subject of sexual development for discussion.

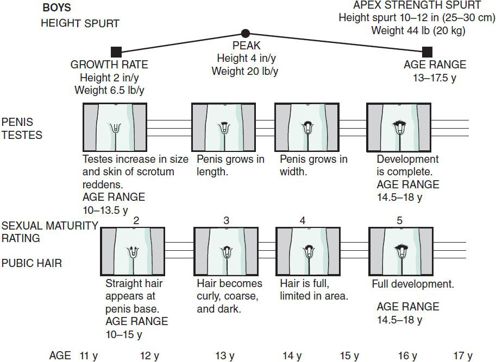

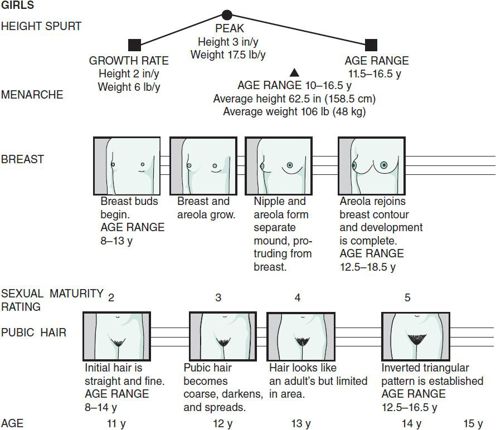

A pictorial chart of sexual development is useful for showing the patient how development is proceeding and what changes to expect. Figure 4–3 shows the relationship between height, penis and testes development, and pubic hair growth in the male, and Figure 4–4 shows the relationship between height, breast development, menstruation, and pubic hair growth in the female. Although teenagers may not admit that they are interested in this subject, they are usually attentive when it is raised. This discussion is particularly useful in counseling teenagers who lag behind their peers in physical development.

Figure 4–3. Adolescent male sexual maturation and growth.

Figure 4–3. Adolescent male sexual maturation and growth.

Figure 4–4. Adolescent female sexual maturation and growth.

Figure 4–4. Adolescent female sexual maturation and growth.

Because teenagers are sensitive about their changing bodies, it is useful to comment during the examination: “Your heart sounds fine. I feel a small lump under your right breast. This is very common during puberty in boys. It is called gynecomastia and should disappear in 6 months to a year.”

Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2007.

Ford C, English A, Sigman G: Confidential health care for adolescents: position paper for the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 2004;35:160 [PMID: 15298005].

GROWTH & DEVELOPMENT

PUBERTY

Pubertal growth and physical development are a result of activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in late childhood. Before puberty, pituitary and gonadal hormone levels are low. At onset of puberty, the inhibition of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus is removed, allowing pulsatile production and release of the gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). In early to middle adolescence, pulse frequency and amplitude of LH and FSH secretion increase, stimulating the gonads to produce estrogen or testosterone. In females, FSH stimulates ovarian maturation, granulosa cell function, and estradiol secretion. LH is important in ovulation and also is involved in corpus luteum formation and progesterone secretion. Initially, estradiol inhibits the release of LH and FSH. Eventually, estradiol becomes stimulatory, and the secretion of LH and FSH becomes cyclic. Estradiol levels progressively increase, resulting in maturation of the female genital tract and breast development.

In males, LH stimulates the interstitial cells of the testes to produce testosterone. FSH stimulates the production of spermatocytes in the presence of testosterone. The testes also produce inhibin, a Sertoli cell protein that inhibits the secretion of FSH. During puberty, circulating testosterone levels increase more than 20-fold. Levels of testosterone correlate with the physical stages of puberty and the degree of skeletal maturation.

PHYSICAL GROWTH

A teenager’s weight almost doubles in adolescence, and height increases by 15%–20%. During puberty, major organs double in size, except for lymphoid tissue, which decreases in mass. Before puberty, there is little difference in the muscular strength of boys and girls. The muscle mass and muscle strength both increase during puberty, with maximal strength lagging behind the increase in mass by many months. Boys attain greater strength and mass, and strength continues to increase into late puberty. Although motor coordination lags behind growth in stature and musculature, it continues to improve as strength increases.

The pubertal growth spurt begins nearly 2 years earlier in girls than in boys. Girls reach peak height velocity between ages 11½ and 12 years, and boys between ages 13½ and 14 years. Linear growth at peak velocity is 9.5 cm/y ± 1.5 cm in boys and 8.3 cm/y ± 1.2 cm in girls. Pubertal growth lasts about 2–4 years and continues longer in boys than in girls. By age 11 years in girls and age 12 years in boys, 83%–89% of ultimate height is attained. An additional 18–23 cm in females and 25–30 cm in males is achieved during late pubertal growth. Following menarche, height rarely increases more than 5–7.5 cm.

In boys, the lean body mass increases from 80% to 85% to approximately 90% at maturity. Muscle mass doubles between 10 and 17 years. By contrast, in girls, the lean body mass decreases from approximately 80% of body weight in early puberty to approximately 75% at maturity.

SEXUAL MATURATION

Sexual maturity rating (SMR) is useful for categorizing genital development. SMR staging includes age ranges of normal development and specific descriptions for each stage of pubic hair growth, penis, and testis development in boys, and breast maturation in girls. Figures 4–3 and 4–4 show this chronologic development. SMR 1 is prepuberty and SMR 5 is adult maturity. In SMR 2 the pubic hair is sparse, fine, nonpigmented, and downy; in SMR 3, the hair becomes pigmented and curly and increases in amount; and in SMR 4, the hair is adult in texture but limited in area. The appearance of pubic hair precedes axillary hair by more than 1 year. Male genital development begins with SMR 2 during which the testes become larger and the scrotal skin reddens and coarsens. In SMR 3, the penis lengthens; and in SMR 4, the penis enlarges in overall size and the scrotal skin becomes pigmented.

Female breast development follows a predictable sequence. Small, raised breast buds appear in SMR 2. In SMR 3, the breast and areolar tissue generally enlarge and become elevated. The areola and nipple form a separate mound from the breast in SMR 4, and in SMR 5 the areola assumes the same contour as the breast.

There is great variability in the timing and onset of puberty and growth, and psychosocial development does not always parallel physical changes. Chronologic age, therefore, may be a poor indicator of physiologic and psychosocial development. Skeletal maturation correlates well with growth and pubertal development.

Teenagers began entering puberty earlier in the last century because of better nutrition and socioeconomic conditions. In the United States, the average age at menarche is 12.53 years, but varies by race and ethnicity; 12.57 for non-Hispanic whites; 12.09 years in non-Hispanic blacks, and 12.09 for Mexican American girls. Among girls reaching menarche, the average weight is 48 kg, and the average height is 158.5 cm. Menarche may be delayed until age 16 years or may begin as early as age 10. Although the first measurable sign of puberty in girls is the beginning of the height spurt, the first conspicuous sign is usually the development of breast buds between 8 and 11 years. Although breast development usually precedes the growth of pubic hair, the sequence may be reversed. A common concern for girls at this time is whether the breasts will be of the right size and shape, especially because initial breast growth is often asymmetrical. The growth spurt starts at about age 9 years in girls and peaks at age 11½ years, usually at SMR 3–4 breast development and SMR 3 pubic hair development. The spurt usually ends by age 14 years. Girls who mature early will reach peak height velocity sooner and attain their final height earlier. Girls who mature late will attain a greater final height because of the longer period of growth before the growth spurt ends. Final height is related to skeletal age at onset of puberty as well as genetic factors. The height spurt correlates more closely with breast developmental stages than with pubic hair stages.

The first sign of puberty in the male, usually between ages 10 and 12 years, is scrotal and testicular growth. Pubic hair usually appears early in puberty but may do so any time between ages 10 and 15 years. The penis begins to grow significantly a year or so after the onset of testicular and pubic hair development, usually between ages 10 and 13½ years. The first ejaculation usually occurs about 1 year after initiation of testicular growth, but its timing is highly variable. About 90% of boys have this experience between ages 11 and 15 years. Gynecomastia, a hard nodule under the nipple, occurs in a majority of boys, with a peak incidence between ages 14 and 15 years. Gynecomastia usually disappears within 6 months to 2 years. The height spurt begins at age 11 years but increases rapidly between ages 12 and 13 years, with the peak height velocity reached at age 13½ years. The period of pubertal development lasts much longer in boys and may not be completed until age 18 years. The height velocity is higher in males (8–11 cm/y) than in females (6.5–9.5 cm/y). The development of axillary hair, deepening of the voice, and the development of chest hair in boys usually occur in mid-puberty, about 2 years after onset of growth of pubic hair. Facial and body hair begin to increase at age 16–17 years.

Herman-Giddens ME, Steffes J, Harris D et al: Secondary sexual characteristics in boys: data from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network. Pediatrics 2012;130(5):e1058-e1068 [PMID: 23085608].

Lee JM, Kaciroti N, Appugliese D et al: Body mass index and timing of pubertal initiation in boys. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:139 [PMID: 20124142].

Rosen DS: Physiologic growth and development during adolescence. Pediatr Rev 2004;25:194 [PMID: 15173452].

Rosenfield RL, Lipton RB, Drum ML: Thelarche, pubarche, and menarche attainment in children with normal and elevated body mass index. Pediatrics 2009;123:84 [PMID: 19117864].

Susman EJ et al: Longitudinal development of secondary sexual characteristics in girls and boys between ages 9½ and 15½ years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164(2):166–173 [PMID: 20124146].

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Adolescence is a period of progressive individuation and separation from the family. Adolescents must learn who they are, decide what they want to do, and identify their personal strengths and weaknesses. Because of the rapidity of physical, emotional, cognitive, and social growth during adolescence, it is useful to divide it into three phases. Early adolescence is roughly from 10 to 13 years of age; middle adolescence is from 14 to 16 years; and late adolescence is from 17 years and later.

Early Adolescence

Early adolescence is characterized by rapid growth and development of secondary sex characteristics. Body image, self-concept, and self-esteem fluctuate dramatically. Concerns about how personal growth and development deviate from that of peers may be great, especially in boys with short stature or girls with delayed breast development or delayed menarche. Although there is a certain curiosity about sexuality, young adolescents generally feel more comfortable with members of the same sex. Peer relationships become increasingly important. Young teenagers still think concretely and cannot easily conceptualize about the future. They may have vague and unrealistic professional goals, such as becoming a movie star or a lead singer in a rock group.

Middle Adolescence

During middle adolescence, as rapid pubertal development subsides, teenagers become more comfortable with their new bodies. Intense emotions and wide swings in mood are typical. Although some teenagers go through this experience relatively peacefully, others struggle. Cognitively, the middle adolescent moves from concrete thinking to formal operations and abstract thinking. With this new mental power comes a sense of omnipotence and a belief that the world can be changed by merely thinking about it. Sexually active teenagers may believe they do not need to worry about using contraception because they can’t get pregnant (“it won’t happen to me”). Sixteen-year-old drivers believe they are the best drivers in the world and think the insurance industry is conspiring against them by charging high rates for automobile insurance. With the onset of abstract thinking, teenagers begin to see themselves as others see them and may become extremely self-centered. Because they are establishing their own identities, relationships with peers and others are narcissistic. Experimenting with different self-images is common. As sexuality increases in importance, adolescents may begin dating and experimenting with sex. Relationships tend to be one-sided and narcissistic. Peers determine the standards for identification, behavior, activities, and clothing and provide emotional support, intimacy, empathy, and the sharing of guilt and anxiety during the struggle for autonomy. The struggle for independence and autonomy is often a stressful period for both teenagers and parents.

Late Adolescence

During late adolescence, the young person generally becomes less self-centered and more caring of others. Social relationships shift from the peer group to the individual. Dating becomes much more intimate. By 10th grade, 40.9% of adolescents (41.9% of males and 39.6% of females) have had sexual intercourse, and by 12th grade, this has increased to 62.3% (59.6% of males and 65% of females). Abstract thinking allows older adolescents to think more realistically about their plans for the future. This is a period of idealism; older adolescents have rigid concepts of what is right or wrong.

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation develops during early childhood. Gender identity is established by age 2 years, and a sense of masculinity or femininity usually solidifies by age 5 or 6 years. Homosexual adults describe homosexual feelings during late childhood and early adolescence, years before engaging in overt homosexual acts.

Although only 5%–10% of American young people acknowledge having had homosexual experiences and only 5% feel that they are or could be gay, homosexual experimentation is common, especially during early and middle adolescence. Experimentation may include mutual masturbation and fondling the genitals and does not by itself cause or lead to adult homosexuality. Theories about the causes of homosexuality include genetic, hormonal, environmental, and psychological models.

The development of homosexual identity in adolescence commonly progresses through two stages. The adolescent feels different and develops a crush on a person of the same sex without clear self-awareness of a gay identity and then goes through a coming-out phase in which the homosexual identity is defined for the individual and revealed to others. The coming-out phase may be a difficult period for the young person and the family. The young adolescent is afraid of societal bias and seeks to reject homosexual feelings. The struggle with identity may include episodes of both homosexual and heterosexual promiscuity, STI, depression, substance abuse, attempted suicide, school avoidance and failure, running away from home, and other crises.

In a clinical setting, the issue of homosexual identity most often surfaces when the teenager is seen for an STI, family conflict, school problem, attempted suicide, or substance abuse rather than as a result of a consultation about sexual orientation. Pediatricians should be aware of the psychosocial and medical implications of homosexual identity and be sensitive to the possibility of these problems in gay adolescents. Successful management depends on the physician’s ability to gain the trust of the gay adolescent and on the physician’s knowledge of the wide range of medical and psychological problems for which gay adolescents are at risk. Pediatricians must be nonjudgmental in posing sexual questions if they are to be effective in encouraging the teenager to share concerns. Physicians who for religious or other personal reasons cannot be objective must refer the homosexual patient to another professional for treatment and counseling.

Brewster KL, Tillman KH: Sexual orientation and substance use among adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health 2012;102(6):1168–1176 [PMID: 22021322].

Frankowski BL: American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Sexual orientation and adolescents. Pediatrics 2004; 113:1827 [PMID: 15173519].

Gutgesell ME, Payne N: Issues of adolescent psychological development in the 21st century. Pediatr Rev 2004;25:79 [PMID: 14993515].

Marshal MP et al: Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: a meta-analytic review. J Adolesc Health 2011;49(2):115–123 [PMID: 21783042].

Silenzio VM et al: Sexual orientation and risk factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health 2007;97(11):2017–2019 [PMID: 17901445].

BEHAVIOR & PSYCHOLOGICAL HEALTH

It is not unusual for adolescents to seek medical attention for apparently minor complaints. In early adolescence, teenagers may worry about normal developmental changes such as gynecomastia. They may present with vague symptoms, but have a hidden agenda of concerns about pregnancy or an STI. Adolescents with emotional disorders often present with somatic symptoms—abdominal pain, headaches, dizziness, syncope, fatigue, sleep problems, and chest pain—which appear to have no biologic cause. The emotional basis of such complaints may be varied: somatoform disorder, depression, or stress and anxiety.

PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGIC SYMPTOMS & CONVERSION REACTIONS

The most common somatoform disorder of adolescence is conversion disorder or conversion reaction. A conversion reaction is a psychophysiologic process in which unpleasant feelings, especially anxiety, depression, and guilt, are communicated through a physical symptom. Psychophysiologic symptoms result when anxiety activates the autonomic nervous system, causing symptoms such as tachycardia, hyperventilation, and vasoconstriction. The emotional feeling may be threatening or unacceptable to the individual who expresses it as a physical symptom rather than verbally. The process is unconscious, and the anxiety or unpleasant feeling is dissipated by the somatic symptom. The degree to which the conversion symptom lessens anxiety, depression, or the unpleasant feeling is referred to as primary gain. Conversion symptoms not only diminish unpleasant feelings but also release the adolescent from conflict or an uncomfortable situation. This is called secondary gain. Secondary gain may intensify the symptoms, especially with increased attention from concerned parents and friends. Adolescents with conversion symptoms tend to have overprotective parents and become increasingly dependent on their parents as the symptom becomes a major focus of concern in the family.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Symptoms may appear at times of stress. Nervous, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular symptoms are common and include paresthesias, anesthesia, paralysis, dizziness, syncope, hyperventilation, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Specific symptoms may reflect existing or previous illness (eg, pseudoseizures in adolescents with epilepsy) or modeling of a close relative’s symptom (eg, chest pain in a boy whose grandfather died of a heart attack). Conversion symptoms are more common in girls than in boys. Although they occur in patients from all socioeconomic levels, the complexity of the symptom may vary with the sophistication and cognitive level of the patient.

History and physical findings are usually inconsistent with a physical cause of symptoms. Conversion symptoms occur most frequently during stress and in the presence of individuals meaningful to the patient. The common personality traits of these patients include egocentricity, emotional lability, and dramatic, attention-seeking behaviors.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Conversion reactions must be differentiated from hypochondriasis, which is a preoccupation with developing or having a serious illness despite medical reassurance that there is no evidence of disease. Over time, the fear of one disease may give way to concern about another. In contrast to patients with conversion symptoms, who seem relieved if an organic cause is considered, patients with hypochondriasis become more anxious when such a cause is considered.

Malingering is uncommon during adolescence. The malingering patient consciously and intentionally fabricates or exaggerates physical or psychological symptoms. Such patients are motivated by external incentives such as avoiding work, evading criminal prosecution, obtaining drugs, or obtaining financial compensation. These patients may be hostile and aloof. Parents of patients with conversion disorders and malingering have a similar reaction to illness. They have an unconscious psychological need to have sick children and reinforce their child’s behavior.

Somatic delusions are physical symptoms, often bizarre, that accompany other signs of mental illness. Examples are visual or auditory hallucinations, delusions, incoherence or loosening of associations, rapid shifts of affect, and confusion.

Treatment

Treatment

The physician must emphasize from the outset that both physical and emotional causes of the symptom will be considered. The relationship between physical causes of emotional pain and emotional causes of physical pain should be described to the family, using examples such as stress causing an ulcer or making a severe headache worse. The patient should be encouraged to understand that the symptom may persist and that at least a short-term goal is to continue normal daily activities. Medication is rarely helpful. If the family will accept it, psychological referral is often a good initial step toward psychotherapy. If the family resists psychiatric or psychological referral, the pediatrician may need to begin to deal with some of the emotional factors responsible for the symptom while building rapport with the patient and family. Regular appointments should be scheduled. During visits, the teenager should be seen first and encouraged to talk about school, friends, the relationship with the parents, and the stresses of life. Discussion of the symptom itself should be minimized; however, the physician should be supportive and must never suggest that the pain is not real. As parents gain insight into the cause of the symptom, they will become less indulgent and facilitate resumption of normal activities. If management is successful, the adolescent will gain coping skills and become more independent, while decreasing secondary gain.

If the symptom continues to interfere with daily activities and if the patient and parents feel that no progress is being made, psychological referral is indicated. A psychotherapist experienced in treating adolescents with conversion reactions is in the best position to establish a strong therapeutic relationship with the patient and family. After referral is made, the pediatrician should continue to follow the patient to ensure compliance with psychotherapy.

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

Kreipe RE: The biopsychosocial approach to adolescents with somatoform disorders. Adolesc Med Clin 2006;17:1 [PMID: 16473291].

Silber TJ: Somatization disorders: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Pediatr Rev 2011;32(2):56–63 [PMID: 21285301].

DEPRESSION (SEE ALSO CHAPTER 7)

Symptoms of clinical depression (lethargy, loss of interest, sleep disturbances, decreased energy, feelings of worthlessness, and difficulty concentrating) are common during adolescence. The intensity of feelings during adolescence, often in response to seemingly trivial events such as a poor grade on an examination or not being invited to a party, makes it difficult to differentiate severe depression from normal sadness or dejection. In less severe depression, sadness or unhappiness associated with problems of everyday life is generally short-lived. The symptoms usually result in only minor impairment in school performance, social activities, and relationships. Symptoms respond to support and reassurance.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

The presentation of serious depression in adolescence may be similar to that in adults, with vegetative signs—depressed mood, crying spells, inability to cry, discouragement, irritability, a sense of emptiness and futility, negative expectations of oneself and the environment, low self-esteem, isolation, helplessness, diminished interest or pleasure in activities, weight loss or weight gain, insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness, and diminished ability to think or concentrate. In adolescents, it is not unusual for a serious depression to be masked because the teenager cannot tolerate the severe feelings of sadness. Such a teenager may present with recurrent or persistent psychosomatic complaints, such as abdominal pain, chest pain, headache, lethargy, weight loss, dizziness, syncope, or other nonspecific symptoms. Other behavioral manifestations of masked depression include truancy, running away from home, defiance of authorities, self-destructive behavior, vandalism, drug and alcohol abuse, sexual acting-out, and delinquency.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

A complete history and physical examination and review of the past medical and psychosocial history should be performed. The family history should be explored for psychiatric problems. Early onset depression and bipolar illness are more likely to occur in families with a multigenerational history of early onset and chronic depression. The lifetime risk of depressive illness in first-degree relatives of adult depressed patients is between 18% and 30%.

The teenager should be questioned about the symptoms of depression and, specifically, about suicidal ideation or preoccupation with thoughts of death. The history should include an assessment of school performance, looking for signs of academic deterioration, excessive absence, cutting class, changes in work or other outside activities, and changes in the family (eg, separation, divorce, serious illness, loss of employment by a parent, recent move to a new school, increasing quarrels or fights with parents, or death of a close relative). The teenager may have withdrawn from friends or family or switched allegiance to a new group of friends. The physician should inquire about possible physical and sexual abuse, drug and alcohol abuse, conflicts with the police, sexual acting-out, running away from home, unusually violent or rebellious behavior, or radical personality changes. Patients with vague somatic complaints or concerns about having a fatal illness may have an underlying affective disorder.

Adolescents with symptoms of depression require a thorough medical evaluation to rule out contributing or underlying medical illness. Among the medical conditions associated with affective disorders are eating disorders, organic central nervous system disorders (tumors, vascular lesions, closed head trauma, and subdural hematomas), metabolic and endocrinologic disorders (hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, Cushing syndrome, Addison disease, or premenstrual syndrome), Wilson disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, infections (infectious mononucleosis or syphilis), and mitral valve prolapse. Marijuana use, phencyclidine abuse, amphetamine withdrawal, and excessive caffeine intake can cause symptoms of depression. Common medications, including birth control pills, anticonvulsants, and β-blockers, may cause depressive symptoms.

Some screening laboratory studies for organic disease are indicated, including complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, urinalysis, serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, serum calcium, thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), Venereal Disease Research Laboratory testing or rapid plasma reagin, and liver enzymes. Although metabolic markers such as abnormal secretion of cortisol, growth hormone, and thyrotropin-releasing hormone have been useful in confirming major depression in adults, these neurobiologic markers are less reliable in adolescents.

Treatment

Treatment

The primary care physician may be able to counsel adolescents and parents if depression is mild or situational and the patient is not contemplating suicide or other life-threatening behaviors. If there is evidence of a long-standing depressive disorder, suicidal thoughts, or psychotic thinking, or if the physician does not feel prepared to counsel the patient, psychological referral should be made.

Counseling involves establishing and maintaining a positive supportive relationship; following the patient at least weekly; remaining accessible to the patient at all times; encouraging the patient to express emotions openly, defining the problem, and clarifying negative feelings, thoughts, and expectations; setting realistic goals; helping to negotiate interpersonal crises; teaching assertiveness and social skills; reassessing the depression as it is expressed; and staying alert to the possibility of suicide.

Patients with bipolar disease or those with depression that is unresponsive to supportive counseling should be referred to a psychiatrist for evaluation and antidepressant medication. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a “black box warning” alerting providers that using antidepressants in children and adolescents may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Adolescents taking these medications should be monitored closely.

Birmaher B et al: Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:795 [PMID: 19448190].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. (2010). Available from www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars.

March JS, Vitiello B: Clinical messages from the Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS). Am J Psychiatry 2009;166(10):1118–1123 [PMID: 19723786].

Simon GE: The antidepressant quandary—considering suicide risk when treating adolescent depression. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2722 [PMID: 17192536].

Wilkinson P et al: Treated depression in adolescents: predictors of outcome at 28 weeks. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194(4):334–341 [PMID: 19336785].

Zuckerbrot RA et al: Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): I. Identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics 2007;120:e1299 [PMID: 17974723].

ADOLESCENT SUICIDE (SEE ALSO CHAPTER 7)

In 2010, suicide was the third leading cause of death among persons aged 15–24 years, resulting in 4600 deaths, at a rate of 10.5 deaths per 100,000 population. The most common methods used in suicides of adolescents and young adults included firearms (44%), suffocation (40%) and poisoning (8%). Among young adults ages 15 to 24 years old, there are approximately 100–200 attempts for every completed suicide.

In 2011, data from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System showed that 15.8% of high school students had seriously considered attempting suicide during the 12 months prior to the survey. Overall, 7.8% of high school students reported having attempted suicide one or more times in the past 12 months, reflecting a significant increase since 2009 (6.3%). Female students were more likely than males to have considered suicide, and females (9.8%) were more likely to report at least one suicide attempt than males (5.8%). The incidence of unsuccessful suicide attempts is three times higher in females than in males. Firearms account for approximately 50% of suicide deaths in both males and females.

Mood swings are common in adolescence. Short periods of depression are common and may be accompanied by thoughts of suicide. Normal adolescent mood swings rarely interfere with sleeping, eating, or normal activities. Acute depressive reactions (transient grief responses) to the loss of a family member or friend may cause depression lasting for weeks or even months. An adolescent who is unable to work through this grief can become increasingly depressed. A teenager who is unable to keep up with schoolwork, does not participate in normal social activities, withdraws socially, has sleep and appetite disturbances, and has feelings of hopelessness and helplessness should be considered at increased risk for suicide.

Angry teenagers attempting to influence others by their actions may be suicidal. They may be only mildly depressed and may not have any long-standing wish to die. Teenagers in this group, usually females, may attempt suicide or make an impulsive suicidal gesture as a way of getting back at someone or gaining attention by frightening another person. Adolescents with serious psychiatric disease such as acute schizophrenia or psychotic depressive disorder are also at risk for suicide.

Risk Assessment

Risk Assessment

The physician must determine the extent of the teenager’s depression and the risk that he or she might inflict self-injury. Evaluation should include interviews with both the teenager and the family. The history should include the medical, social, emotional, and academic background. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a nine-item standardized depression questionnaire that is incorporated in the Adolescent Health Questionnaire in the section labeled “Health Concerns” (see Figure 4–2.).

Treatment

Treatment

The primary care physician is often in a unique position to identify an adolescent at risk for suicide because many teenagers who attempt suicide seek medical attention in the weeks preceding the attempt. These visits are often for vague somatic complaints. If the patient shows evidence of depression, the physician must assess the severity of the depression and suicidal risk. The pediatrician should always seek emergency psychological consultation for any teenager who is severely depressed, psychotic, or acutely suicidal. It is the responsibility of the psychologist or psychiatrist to assess the seriousness of suicidal ideation and decide whether hospitalization or outpatient treatment is most appropriate. Adolescents with mild depression and low risk for suicide should be followed closely, and the extent of the depression should be assessed on an ongoing basis. If it appears that the patient is worsening or is not responding to supportive counseling, referral should be made.

Brent DA et al: The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters study (TASA): predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48(10):987–996 [PMID: 19730274].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Suicide trends among youths and young adults aged 10–24 years—United States, 1990–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56(35): 905–908 [PMID: 17805220].

Connor J, Rueter M: Predicting adolescent suicidality: comparing multiple informants and assessment techniques. J Adolesc 2009;32(3):619–631 [PMID: 18708245].

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL: The PHQ-9: a new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 2002;32:509–521.

Prager LM: Depression and suicide in children and adolescents. Pediatr Rev 2009;30(6):199–205 [PMID: 19487428].

Richardson LP et al: Evaluation of the patient health questionnaire-9 item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics 2010;126(6):1117–1123 [PMID: 21041282].

Shain BN, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence: Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics 2007;120:669 [PMID: 17766542].

Wilkinson P et al: Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT). Am J Psychiatry 2011;168(5):495–501 [PMID: 21285141].

Williams SB et al: Screening for child and adolescent depression in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics 2009;123(4): e716–e735 [PMID: 19336361].

SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Substance abuse is a complex problem for adolescents and the broader society. See Chapter 5 for an in-depth look at this issue.

EATING DISORDERS (SEE CHAPTER 6)

OVERWEIGHT & OBESITY (SEE ALSO CHAPTER 11)

Background

Background

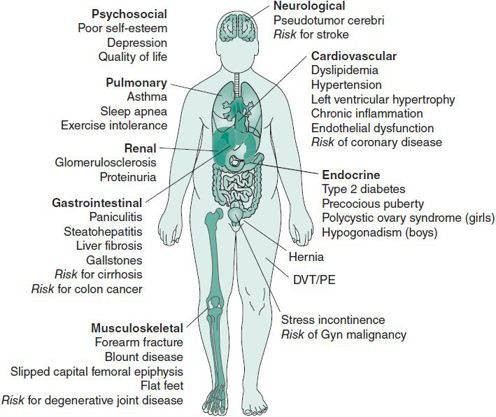

The prevalence of obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 95th percentile for age and gender) among adolescents 12–19 years has increased from 5% to 17% in the past 25 years, with higher rates in black and Hispanic youth. Furthermore, an adolescent who is overweight (BMI between 85th and 95th percentiles) has a 70% chance of becoming an obese adult. Figure 4–5 illustrates the multiple morbidities related to overweight and obesity during adolescence and the risk of the additional comorbidities associated with obesity in adulthood. Perhaps the most common short-term morbidities for overweight and obese adolescents are psychosocial, including social marginalization, poor self-esteem, depression, and poor quality of life. Like physical comorbidities, these psychosocial complications can extend into adulthood. Recent data on adolescent dietary and physical activity behaviors that potentiate overweight and obesity indicate that almost 80% of teens have deficient fiber intake, 63% have less than the recommended level of physical activity (60 minutes per day, 5 days per week), 33% watch 3 or more hours of television per average school day, and 25% participate in nonacademic computer activities for more than 3 hours per average school day.

Figure 4–5. Complications of obesity. DVT, Deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. (Adapted and reproduced, with permission, from Xanthakos SA, Daniels SR, Inge TH: Bariatric surgery in adolescents: an update. Adolesc Med Clinics 2006;17(3):589–612 [PMID: 17030281].)

Figure 4–5. Complications of obesity. DVT, Deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. (Adapted and reproduced, with permission, from Xanthakos SA, Daniels SR, Inge TH: Bariatric surgery in adolescents: an update. Adolesc Med Clinics 2006;17(3):589–612 [PMID: 17030281].)

Evaluation

Evaluation

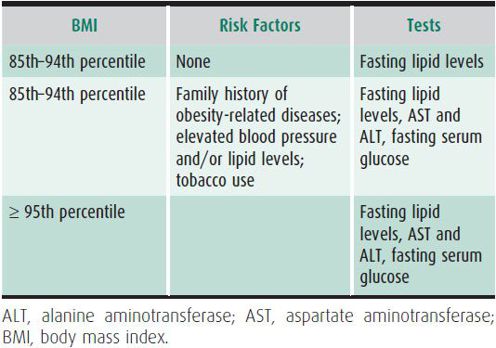

Regular screening for overweight and obesity by measuring BMI during routine visits and providing anticipatory guidance for the adolescent and family regarding healthy nutrition and physical activity are essential for early identification and prevention of overweight and related comorbidities. A family history of obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary heart disease places the overweight young person at even higher risk of developing these comorbidities. Details of individual and family dietary behaviors, assessment of physical activity and time spent with sedentary activities, previous efforts to lose weight, and current readiness to change can identify areas for modifiable lifestyle behaviors to promote weight loss. The review of systems should include questions about symptoms associated with comorbid conditions including insulin resistance and diabetes, gallbladder disease or steatohepatitis, sleep dysfunction, and menstrual irregularities (female patients). If an overweight adolescent is otherwise healthy and has no delay in growth or sexual maturation, an underlying endocrinologic, neurologic, or genetic cause of overweight is unlikely. BMI percentile and the presence of risk factors for morbidities can serve as guides for laboratory evaluations of overweight adolescents in the primary care setting (Table 4–1).

Table 4–1. Screening tests for overweight and obese adolescents in the primary care setting.

Treatment

Treatment

Comprehensive interventions that include both behavioral therapy and modifications in diet and physical activity seem to be the most successful approaches to obesity and its comorbidities, but clinical trials testing these interventions are limited. Several studies of childhood obesity treatment have confirmed the critical importance of parental participation in weight control programs. The greater independence of adolescents means that providers must discuss health behaviors directly with them while involving parents in the discussions and encouraging the whole family to make the home environment and family lifestyle a healthy one.

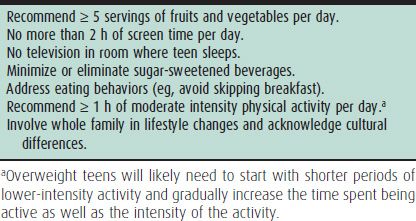

The most current evidence on obesity treatment in the pediatric population recommends a four-stage approach that includes (1) prevention plus (Table 4–2); (2) structured weight management; (3) comprehensive multidisciplinary intervention; and (4) tertiary care intervention. The appropriate weight management stage for each patient is based on age, BMI percentile, comorbid disease, and past obesity treatment.

Table 4–2. Components of stage 1, “prevention plus” healthy lifestyle approach to weight management for adolescents.

Providers caring for overweight and obese adolescents should identify comorbidities and treat them as indicated. For example, an overweight teen with daytime somnolence and disruptive snoring may need a sleep study to evaluate for obstructive sleep apnea. A nonpregnant overweight young woman with acanthosis nigricans and oligomenorrhea should be evaluated for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). There are few guidelines regarding pharmacotherapy for obesity in the adolescent. Medication options include sibutramine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) that is approved for patients age 16 and older, and orlistat, a lipase inhibitor approved for patients age 12 and older. In general, obese adolescents who might benefit from medication should be referred to a multidisciplinary weight loss program, as medication should only be used as part of a comprehensive program which includes diet, physical activity, and behavioral modifications. Bariatric surgery is reserved for severely obese adolescents who are physically mature, who have a BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more (or ≥ 40 kg/m2 with significant comorbidities), who have failed a structured 6-month weight loss program, and who are deemed by psychological assessment to be capable of adhering to the long-term lifestyle changes required after surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree