Adnexal Masses

Marc R. Laufer

The adnexa refer to the structures lateral to the uterus and include the ovary, fallopian tube, and broad ligament. Masses of the adnexa can be cystic, solid, or both. Adnexal abnormalities include ovarian, tubal, paratubal, and broad ligament cysts; abscesses (tubal or ovarian); ectopic pregnancy (tubal or ovarian); and benign or malignant tubal or ovarian masses.

Fallopian Tube/Broad Ligament Masses

Fallopian tube masses are most commonly cysts that are mesonephric remnants. Persistent wolffian duct derivatives are commonly found in normal females (1,2). These remnants can result in pain or adnexal masses as follows:

A hydatid of Morgagni cyst itself does not usually cause pain (Fig. 21-1), although torsion of the cyst can result in colicky, lower abdominal/pelvic pain with or without nausea and vomiting. Once torsion has occurred, the cyst may become gangrenous. Intermittent torsion of the cyst can also occur, resulting in intermittent symptoms. These cysts can be removed laparoscopically; the fallopian tube can be salvaged and not compromised.

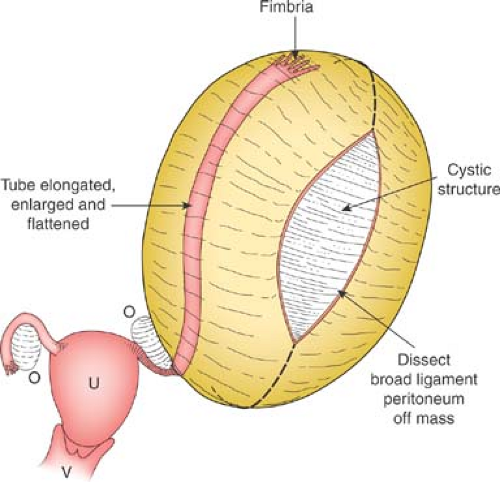

Cysts of the broad ligament can result in large, simple, cystic, adnexal masses (Fig. 21-2). Patients may present with pain and/or abdominal distention, or the cysts may be identified on routine examination. The cysts are usually simple in appearance on ultrasound. Surgery may be indicated if there is pain or abdominal distention; resection is not mandatory for small asymptomatic broad ligament cysts, as these can be benign embryologic remnants. If the cystic mass increased in size, it can be an ovarian cyst growing into the broad ligament or an enlarging embryonic remnant.

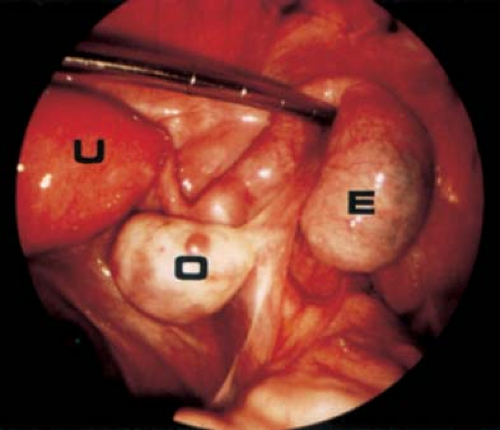

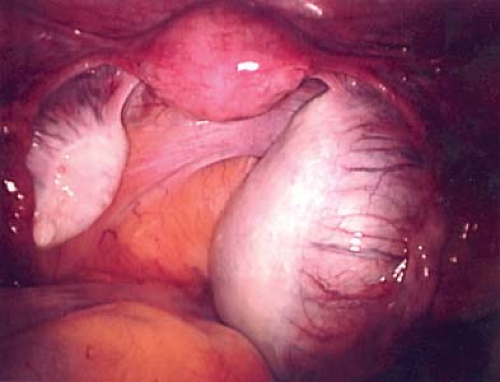

If surgery is undertaken, care must be taken to identify the cyst as arising from the broad ligament, with appropriate identification of the fallopian tube (Fig. 21-3), as the fallopian tube may be distended and stretched over the surface of the cyst (Fig. 21-2). This can be performed by laparoscopy or by laparotomy. After identification of the fallopian tube, an incision is made in the peritoneum of the broad ligament parallel to the fallopian tube. Aquadissection is helpful to separate the cyst from the tube and the delicate blood vessels of the broad ligament. The initial dissection is facilitated by keeping the cyst intact and then it can be drained to help visualize the base for removal of the cyst wall. After removal of the cyst, the distended fallopian tube and redundant peritoneum are left to regress to normal size (Fig. 21-4).

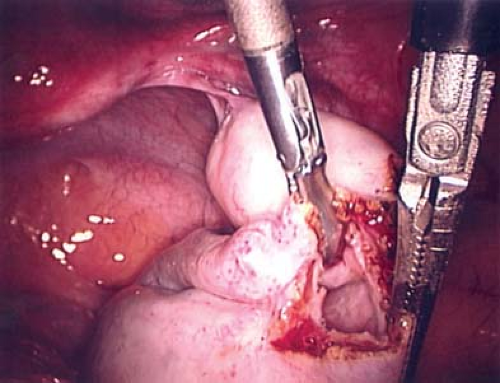

Ectopic pregnancy [EP] can cause a tubal mass (Fig. 21-5). Ectopic pregnancies are typically diagnosed by the presence of pain, irregular bleeding, and abnormally rising human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) levels (see Chapter 25). EP is typically managed with the use of medical therapy, but if a surgical procedure is performed a linear salpingostomy is the best approach to remove the EP and salvage the fallopian tube. In cases where the tube is unable to be salvaged, a salpingectomy is performed.

Tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) is a polymicrobial infection of the fallopian tube and/or ovary and results from either an ascending infection or intra-abdominal spread of infection. Ascending infections of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) are addressed in Chapter 18. It should be noted that non–sexually active young women can also have a TOA, most likely from a nonascending infection. This is most commonly seen in young women with

prior abdominal surgery and complex structural issues such as cloacal malformation or exstrophy (see Chapter 12).

prior abdominal surgery and complex structural issues such as cloacal malformation or exstrophy (see Chapter 12).

Ovarian Masses

Ovarian masses in infants, children, and adolescents may result from functional cysts or benign or malignant neoplasms. Ovarian tumors are the most common genital neoplasms that occur during childhood, accounting for about 1% of all malignant neoplasms found in the age range of 0 to 17 years (3,4). Historically, it was widely believed that all ovaries containing masses discovered in infants, children, and adolescents should be removed surgically, but with the identification of serum tumor markers and advances in radiologic imaging, a more rational and conservative fertility-sparing approach to the management of these ovarian masses has been developed.

Figure 21-4. Fallopian tubes, ovaries, and uterus seen after resection of the broad ligament cyst seen in Fig. 21-2. Notice distorted enlarged left fallopian tube, which will involute and return to a normal size. |

Classification of Ovarian Masses

Ovarian masses may result from functional (nonneoplastic) cysts or benign or malignant neoplasms. The World Health Organization has classified ovarian neoplasms into major categories with differing subtypes, based on histologic cell type and benign versus malignant state (5,6,7). An adapted version is shown in Table 21-1 (5,6,7). In contrast to the adult experience, in which epithelial tumors account for the significant proportion of neoplasms, the majority of tumors in the younger population are of germ cell origin (Table 21-2) (8). Although the majority of lesions in childhood are benign, expedient diagnosis and management is important to lessen the possibility of ovarian torsion and loss of adnexa, and to improve the prognosis for malignant masses.

Fetal Ovarian Cysts

Ovarian cysts have been detected prenatally on routine obstetric ultrasound in 30% to 70% of fetuses depending on the gestational age (9,10,11,12); the true incidence is unknown. With the increased utilization of routine prenatal ultrasound the identification of fetal ovarian cysts has greatly increased (13). The etiology of fetal ovarian cysts is unclear, but most likely they result from a combination of ovarian stimulation by maternal and fetal gonadotropins (see Fig. 6-4) (14). The differential diagnosis of fetal cystic intra-abdominal masses is shown in Table 21-3 (15). An increased incidence of fetal and neonatal follicular cysts has been reported in association with preeclampsia, diabetes mellitus, polyhydramnios, and isoimmunization disease (12,14,16,17).

Table 21-1 Modified World Health Organization’s International Histologic Classification of Ovarian Tumors | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Table 21-2 Primary Ovarian Tumors Treated at the Children’s Hospital Boston (1928–1982) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 21-3 Differential Diagnosis of Fetal/Neonatal Intra-Abdominal Cystic Masses | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Management of Fetal Ovarian Cysts

The majority of antenatal ovarian cysts are unilateral, although both ovaries may be involved (16). Spontaneous regression occurs in both simple and complex fetal cysts both antenatally and postpartum. The first-line management of the patient with antenatally diagnosed ovarian cysts is observation, although the size and composition of the cyst must be considered as the treatment plan is formulated (9,10,11,12,18,19,20). The risks to the fetus of an ovarian cyst may include intracystic hemorrhage, rupture of the cyst with possible hemorrhage, gastrointestinal and urinary tract obstruction, ovarian torsion and necrosis, incarceration into a congenital inguinal hernia, difficulty with delivery due to abdominal dystocia, and respiratory distress at birth due to the mass effect (21,22). Antenatal aspiration of large (>4 cm) ovarian cysts has been advocated to reduce the potential complications (20,23,24,25); however, the role of antenatal cyst aspiration is controversial due to potential misdiagnosis and complications of the aspiration procedure (26). In some fetuses with large cysts (>6 cm) or masses that are not cystic, elective cesarean section may be the preferred route to prevent rupture and/or dystocia. The rate of malignancy is so low that it need not be considered in making therapeutic decisions. Long-term follow-up of children with ovarian cysts diagnosed prenatally has shown the importance of close monitoring of complex cysts in order to alert the clinician to the need for early intervention to avoid impending ovarian loss due to torsion (27).

Neonatal Ovarian Cysts

The most common genitourinary cystic mass not related to the kidney is an ovarian cyst (28). The differential diagnosis of a neonate with a cystic intraperitoneal mass is extensive and includes a number of congenital cystic masses of other intraperitoneal organs, as well as congenital anomalies (see Table 21-3) (15,29). As noted above, the etiology of fetal and neonatal ovarian cysts is unknown, but is most likely the result of maternal and fetal hormonal stimulation in utero. If in utero ovarian torsion occurs, the ovary may undergo necrosis and develop into a calcified persistent mass or may be resorbed.

Clinical Presentation

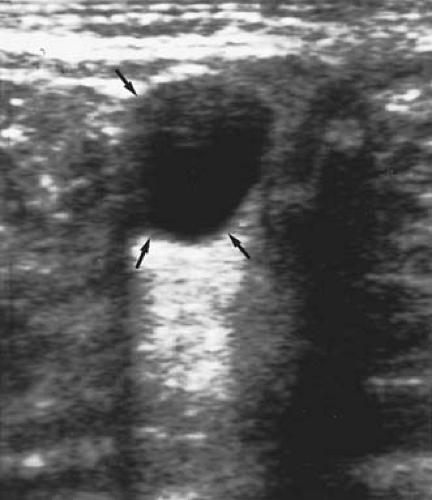

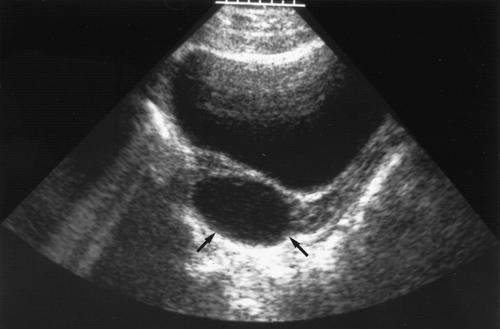

Most neonatal cysts are asymptomatic and identified incidentally on antenatal neonatal ultrasound evaluation for another indication. As neonates have a shallow pelvis, the cysts are often displaced to the mid- or upper abdomen, at which time they are palpable abdominally. On abdominal examination, the ovary containing the cyst is generally freely mobile. Ultrasound reveals a cystic mass that may have a simple (Fig. 21-6) (clear, fluid-filled) or complex (Fig 21-7) (fluid, debris, septa, solid components, echogenic wall) sonographic pattern. The complex appearance on ultrasound may make a precise diagnosis more difficult (15).

Management of Neonatal Ovarian Cysts

Spontaneous regression occurs in these cysts postpartum usually by 3 to 4 months of age, but can take up to a year or longer to regress (30). They should be followed with serial ultrasound examinations to ensure regression. The greatest concern in the neonate with an ovarian cyst is the possibility of torsion with subsequent ovarian loss. If the cyst does not resolve, then either neoplasia is present (unlikely) or torsion with hemorrhage and/or necrosis (see Figs. 13-6 and 13-7) has occurred (11,31).

Figure 21-6. Ultrasound shows a simple cyst (arrows) in a neonate. (Courtesy of Carol Barnewolt, M.D., Children’s Hospital Boston.) |

The traditional management of neonatal cysts that persist for longer than 4 months and are >5 cm or increasing in size is surgery (12,32,33,34,35). Every attempt should be made to salvage the ovary in cases of persistent ovarian cysts; in rare instances, such as cases of torsion with ovarian necrosis, oophorectomy is

necessary (14,25). Figures 21-8 to 21-10 demonstrate the preservation of some normal-appearing ovarian tissue in a case of neonatal ovarian torsion. Based on the rarity of malignancy, every effort should be made to preserve any normal ovarian tissue with an ovarian cystectomy as opposed to an oophorectomy.

necessary (14,25). Figures 21-8 to 21-10 demonstrate the preservation of some normal-appearing ovarian tissue in a case of neonatal ovarian torsion. Based on the rarity of malignancy, every effort should be made to preserve any normal ovarian tissue with an ovarian cystectomy as opposed to an oophorectomy.

Figure 21-7. Ultrasound shows an ovarian cyst containing debris (arrow). (Courtesy of Carol Barnewolt, M.D., Children’s Hospital Boston.) |

It should be noted that infants and children may also have torsion of normal ovaries (see Chapter 13) (36,37,38). It is possible to untwist the vascular pedicle in an attempt to salvage the ovary (39) (see Ovarian and Tubal Torsion below). Neonatal ovarian cysts can be managed preferentially by a laparoscopic approach, but may require a mini-laparotomy (40,41,42,43,44).

Figure 21-9. Resection of torsed ovarian tissue seen in Fig. 21-8. An area of normal-appearing ovarian tissue was separated from the necrotic tissue and was preserved as seen in Fig. 21-10. |

Figure 21-10. Residual normal-appearing ovarian tissue conserved from the case in Figs. 21-8 and 21-9. |

Postpartum cyst aspiration has been advocated to reduce the likelihood of torsion (45). In contrast to antenatal cyst aspiration, the use of neonatal cyst aspiration has been clearly established, because the diagnosis is more certain and the risk of complications is low (46,47). Aspiration of persistent large simple cysts (>5 to 6 cm) is recommended (12). If the cysts recur, then the options include reaspiration or surgical removal.

Ovarian Cysts in the Prepubertal Child

Functional ovarian cysts develop as a result of gonadotropin stimulation of the ovary, and thus the incidence of ovarian cysts decreases in early childhood and then increases as puberty is approached (48,49). Most simple ovarian cysts in children result from failure of a follicle to involute. Many small simple cystic structures (<1 to 1.5 cm) occur in normal ovaries of children and do not require further evaluation.

Some functional cysts will be hormonally active and result in precocious pseudopuberty, with the patient presenting with an episode of vaginal bleeding or premature breast development (see Chapter 7) (50,51,52,53). Hormone-secreting cysts may cause sexual precocity, as is seen in association with the McCune-Albright syndrome (54). These ovarian cysts may respond to medical therapy for McCune-Albright syndrome, but if they persist on therapy, needle aspiration under ultrasound guidance or laparoscopy may be indicated. Cysts may also occur in patients with idiopathic central precocious puberty and would be expected to resolve with the institution of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog therapy (55) (see Chapter 7). When prepubertal ovaries are found to be enlarged and multicystic, an evaluation for thyroid disease is indicated (see Chapter 7). If a child has a cystic mass without precocity, the cyst may well be a paraovarian (see Fig. 21-1) or mesothelial cyst and, if symptomatic, requires excision (see Figs. 21-2 to 21-4).

Nonfunction ovarian cysts also occur in children and will present as nonresolving cystic masses. Although rare, benign epithelial cystic tumors such as serous and mucinous cystadenomas do occur in children, will persist, and require surgical excision (56).

Clinical Presentation

In young children, an ovarian cyst is often discovered by a parent or clinician as an asymptomatic abdominal mass or as increasing abdominal girth. The embryologic ovary migrates from the level of 10th thoracic vertebra (in early life it is characteristically abdominal in location) and during maturation descends to the true pelvis by puberty. Thus, ovarian tumors may present as abdominal masses in the young child (3). Chronic abdominal aching pain, either periumbilical or located in one lower quadrant, may be present. Acute severe pain simulating appendicitis or peritonitis may develop secondary to torsion, perforation, infarction, or hemorrhage from or into a tumor or cyst (see Chapter 13). Patients may experience intermittent pain, presumably because of torsion without complete compromise of the vascular blood supply, that subsequently resolves without therapy. This may also be the warning sign of impending torsion with complete compromise of the blood supply and the need for emergency surgery (see Ovarian and Tubal Torsion below). Nonspecific symptoms including nausea, vomiting, a sense of abdominal fullness or bloating, and urinary frequency or retention may signal the presence of a tumor.

Evaluation of Ovarian Cysts in Prepubertal Girls

Ultrasound is the best method for evaluation of ovarian cysts in prepubertal girls. The mass should be measured, and its characteristics determined (simple, complex, or solid). As discussed in Chapters 13 and 23, Doppler flow ultrasound may or may not be helpful in determining cases of ovarian torsion (see discussion of torsion below); ultrasound determination of a discrepancy in ovarian volume can be helpful in determining ovarian torsion (57).

Management of Ovarian Cysts in Prepubertal Girls

The management of an ovarian cyst in the prepubertal age group depends on the appearance of the cyst on ultrasound and the presence of significant symptomatology. Most likely these cysts will resolve spontaneously and require no intervention.

Rarely a simple ovarian cyst in a prepubertal child will rupture and may result in acute exacerbation of pain. This will most likely be self-limited and requires no surgical intervention.

If the prepubertal ovarian mass is purely cystic or has few internal echoes/debris suggestive of hemorrhage and no other complex features such as septation or calcification (Fig. 21-7), it is almost certainly benign and can be managed by observation (53,58). A follow-up ultrasound scan in 4 to 8 weeks should reveal a decrease in size. If the cyst has not resolved and the ultrasonic characteristics are still reassuring, then continued observation is still appropriate. Warner and associates (59) reported on the conservative management of 51 children with both simple and complex cysts, all >5 cm in diameter. Of these cysts, 90% spontaneously resolved, largely within 2 weeks. Of the 23 children treated surgically either because of initial sonographic appearance or for persistence, 10 were found to have neoplasms (6 teratomas, 2 cystadenomas, 1 granulosa cell tumor, 1 Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor) (59). Thind and colleagues (60) found that in 64 children with simple cysts <5.5 cm in diameter, all of the cysts resolved. These girls, however, tended to have persistent symptoms for a few months followed by spontaneous resolution. The cysts sometimes recurred, although new ovarian cysts also occurred on the contralateral side (60).

If a prepubertal simple ovarian cyst persists, is symptomatic, or is growing in size, then a surgical intervention is indicated. Laparoscopy can be safely performed in young girls and an ovarian cystectomy should be performed with preservation of normal ovarian cortex as opposed to an oophorectomy (see Figs. 21-11 to 21-14). Persistent simple cysts are most likely a mucinous or serous ovarian cyst. Although rare, these cysts can recur (56).

Ovarian masses in prepubertal girls associated with torsion are usually benign (61). In a series of 102 girls (aged 2 days to 20 years) who underwent 106 consecutive ovarian operations, the authors reported that 42% of those who presented with abdominal pain had ovarian torsion. In their series, the ovarian mass was malignant in only one patient. In comparison, 26% of those presenting with an asymptomatic mass were found to have an ovarian malignancy. The management of adnexal torsion involves detorsion of the torsed ovary and preservation of

the ovary unless it is necrotic and nonviable. Ovarian torsion management is more fully discussed below.

the ovary unless it is necrotic and nonviable. Ovarian torsion management is more fully discussed below.

Figure 21-12. Linear incision in normal ovarian cortex to initiate the ovarian cystectomy from Fig. 21-11. |

Figure 21-13. Cyst wall visible after incision and drainage of ovarian cyst in Figs. 21-11 and 21-12. |

Postpubertal Ovarian Cysts

Functional Ovarian Cysts

Functional cysts (20% to 50% of ovarian tumors) are not true neoplasms but rather should be considered a variation of a normal physiologic process (see Chapter 6). Functional cysts include follicular, corpus luteum, and theca-lutein types, all of which are benign and usually self-limited. The incidence of cysts and nonmalignant tumors in the community is probably even higher than indicated in most series, as percentages are based on referred cases and it is not possible to determine the underlying incidence of nonidentified or asymptomatic cysts or masses (8,62).

Figure 21-14. Post–ovarian cystectomy view after removal of cyst wall in Figs. 21-11 to 21-13. Final pathology revealed a benign mucinous cystadenoma. |

The development of simple cysts is quite common in postpubertal girls and adolescents. Most simple cysts result from the failure of the maturing follicle to ovulate and involute. Adolescent ovaries may contain multiple follicles in different stages of development (see Fig. 13-18).

Clinical Presentation

Cysts in the postmenarchal adolescent may be asymptomatic or cause menstrual irregularities, pelvic pain, or, if large, urinary frequency, constipation, or pelvic heaviness. Cysts can rupture, causing intra-abdominal hemorrhage (see Fig. 13-12 and Management of Cysts section, discussed next). Torsion of a cyst causes acute pain, nausea, vomiting, and pallor, often followed by less severe localized pain (63). The white blood cell count may be elevated with a shift to the left, but this is usually a late sign of ischemic or necrotic changes. Examination reveals pain, peritoneal signs, and a tender mass.

Management of Postpubertal Ovarian Cysts

Functional Simple Cysts

In most cases, follicular cysts found on routine examination resolve spontaneously in 1 to 2 months. Ovarian cysts <3 cm are usually normal follicles and require no further evaluation or intervention. If a cyst larger than 6 cm is palpated in an asymptomatic patient and ultrasound or pelvic examination confirms a simple, fluid-filled cyst, the patient may be observed with or without the addition of an oral contraceptive prescribed to suppress the hypothalamic–ovarian axis. The oral contraceptive pill does not “shrink” the existing cyst, but with suppression of the hypothalamic–ovarian axis a new ovarian cyst is unlikely to develop and confuse the clinician as to whether the first cyst resolved and a new one formed or whether the original cyst has persisted. The patient should have a repeat ultrasound to confirm resolution. Patients incidentally found to have small follicular cysts at the time of surgery (e.g., appendectomy) should not undergo cyst aspiration or cystectomy, as these cysts will resolve spontaneously and ovarian or paratubal adhesions may form from ovarian surgery and result in infertility and/or pelvic pain (see Chapter 13) (64,65).

If a fluid-filled cyst increases in size, is larger than 6 cm, or causes symptoms, then a laparoscopic cyst aspiration (with the cyst fluid sent for cytology) or cystectomy (with the cyst wall sent for pathologic evaluation) can be performed (see Figs. 21-11 to 21-14) (66). If surgery is undertaken, ovarian cystectomy is preferred to cyst aspiration due to the high rate of recurrence after aspiration (67). If there is a contraindication to surgery, or if a nonsurgical approach is preferred, ultrasound-guided cyst aspiration can be performed; cyst aspiration does not require anesthesia or a laparoscopic approach.

It should be noted that asymptomatic simple cysts of 6 to 12 cm or larger may also spontaneously resolve and can be safely observed in some patients. If the cyst recurs or operative intervention is needed, the procedure should be conservative with an ovarian cystectomy and not an oophorectomy so that as much ovarian tissue as possible is preserved.

Corpus Luteum

Corpus luteum (yellow body) is the natural result of ovulation and is the hormonally active, progesterone-producing component of the follicular event. These cysts occur often and can reach 5 to 12 cm in diameter if there is bleeding into the corpus luteum itself. These cysts are the result of the

normal formation of a corpus luteum after ovulation (see Chapter 6). Ultrasound is useful to suggest the appearance of a corpus luteum cyst, which contains increased echoes (Fig. 21-15). There may be bleeding into the cyst or rupture with intraperitoneal hemorrhage. The hemorrhage needs to be assessed to determine whether the bleeding appears to be self-limited (in which case the patient can be observed with serial hematocrit readings and examinations) or whether the bleeding is resulting in a significant decrease in hematocrit or changes in vital signs. If it is determined that the patient needs surgery, then she is stabilized and laparoscopy or laparotomy undertaken (58). Free blood and clots (see Fig. 13-12) can be aspirated and hemostasis ensured by fulguration of areas of bleeding via laparoscopy. A hemoperitoneum is not a contraindication to laparoscopy. If the surgeon is not comfortable with laparoscopy for children or if the patient is hypotensive, then a laparotomy is undertaken. Most often the bleeding can be controlled with cauterization or ovarian cystectomy; oophorectomy is not indicated. Conservative management with conservation of normal ovarian tissue is the rule.

normal formation of a corpus luteum after ovulation (see Chapter 6). Ultrasound is useful to suggest the appearance of a corpus luteum cyst, which contains increased echoes (Fig. 21-15). There may be bleeding into the cyst or rupture with intraperitoneal hemorrhage. The hemorrhage needs to be assessed to determine whether the bleeding appears to be self-limited (in which case the patient can be observed with serial hematocrit readings and examinations) or whether the bleeding is resulting in a significant decrease in hematocrit or changes in vital signs. If it is determined that the patient needs surgery, then she is stabilized and laparoscopy or laparotomy undertaken (58). Free blood and clots (see Fig. 13-12) can be aspirated and hemostasis ensured by fulguration of areas of bleeding via laparoscopy. A hemoperitoneum is not a contraindication to laparoscopy. If the surgeon is not comfortable with laparoscopy for children or if the patient is hypotensive, then a laparotomy is undertaken. Most often the bleeding can be controlled with cauterization or ovarian cystectomy; oophorectomy is not indicated. Conservative management with conservation of normal ovarian tissue is the rule.

Figure 21-15. Ultrasound shows a corpus luteum cyst (arrows) in a young woman reporting dull pain. (Courtesy of Carol Barnewolt, M.D., Children’s Hospital Boston.) |

Corpus luteum cysts are often asymptomatic, although they may also cause pain. In the absence of pain or intraperitoneal bleeding, therapy with an oral contraceptive pill (to suppress a new cyst from forming) and observation for 3 months are indicated. If hemorrhage or severe pain occurs or the cyst is large (>6 cm) on initial examination, laparoscopy or laparotomy may be necessary. Due to increased ovarian size and weight, corpus luteum cysts may increase the risk of ovarian torsion (see Figs. 13-11 and 13-14).

Ovarian and/or Tubal Torsion

As mentioned above, the embryologic ovary migrates from the level of 10th thoracic vertebra (in early life it is characteristically abdominal in location) and during maturation descends to the true pelvis by puberty (see Fig. 13-15). Based on the abdominal location of the ovary, and the long utero-ovarian ligament, the normal adnexa of prepubertal girls are at increased risk of torsion. Torsion can occur with a cyst of any size, just as it does with normal adnexa, particularly when long pedicles are present (46,68). When known cysts are followed conservatively, parents or other caregivers should be made aware of the signs and symptoms of torsion (sudden onset of pain, nausea, vomiting, and possible low-grade fever) (see Chapter 13) and urged to seek emergent care without delay.

As noted in Chapter 13, ultrasound may be helpful in determining the presence of ovarian torsion (57,69,70). The classic appearance of peripheral follicles (“string of pearls”) with stromal edema may be helpful in making a diagnosis of torsion (see Fig. 13-13) and a volume discrepancy is also helpful in making the diagnosis (57).

Adnexal torsion should be addressed as a surgical emergency (71,72,73). Patients usually experience sudden onset of pain, nausea, vomiting, and possible low-grade fevers and are found to have peritoneal signs with rebound and/or guarding and possibly a mild leukocytosis (63,74,75,76). Patients may also experience intermittent pain, presumably because of partial or incomplete torsion (without complete compromise of the vascular blood supply), that subsequently resolves without therapy or does not cause complete ischemia. This may also be the warning sign of impending complete torsion with ischemia and death of the ovary, and the need for emergency surgery. If there is a concern for torsion, then a surgical procedure should be carried out for diagnosis and appropriate management.

In cases of ovarian torsion, surgery is indicated at the time of the diagnosis. Ovarian masses in girls and young women (ages 2 days to 20 years) associated with torsion are usually benign (61). In an urgent situation a platelet (PLT) count is readily available and elevated PLT counts are associated with malignancy (77). Torsed ovaries should be “detorsed” laparoscopically with conservation of the ovary (39,71,73,78,79,80,81). The historical concerns regarding blood clots and emboli from detorsion appear to be unfounded. The anatomy should be identified, the contralateral tube and ovary should be visualized and confirmed to be present and normal (asynchronous ovarian torsion has been reported), and the affected tube/ovary should be detorsed and salvaged (82). Even in cases of a “black” tube and/or ovary, detorsion and preservation of the adnexa can be carried out (see Fig. 13-14A–D) (81,82,83). If the ovary appears “black,” then a “bivalve” procedure may help facilitate increased blood flow to the ovary by decreasing the arterial blood pulse pressure and improving blood flow (83). Detorsion and oophoropexy (see below) may be all that is indicated, but if an ovarian cyst is present, then an ovarian cystectomy is performed and not an oophorectomy. Once again, preservation of normal ovarian tissue is the rule. It is our feeling that it is better to leave an ovary in place, even if it looks “dusky” after detorsion and bivalve procedures, as it will most likely maintain function. It is always possible to return to the operating room at a later date to remove an ovary that did not survive (patient has persistence of pain, fevers, increased white blood cell (WBC) count); it is not possible to replace a potentially viable ovary once an oophorectomy has been performed.

Ovarian torsion may occur without diagnosis and/or intervention (84). In this case, the ovary will most likely resorb and/or calcify. It is also possible for the ovary to “autoamputate” and become a sessile complex mass within the abdominal cavity (see Fig. 13-7A,B).

Several weeks to years after adnexal torsion, these same individuals may experience torsion of the other adnexa, and if the second torsed ovary is not salvageable, the individual is sterile (37,38,82). Based on this occurrence of bilateral asynchronous ovarian torsion, oophoropexy should be considered in all cases of ovarian torsion of a normal (ovary without a large cyst that caused the torsion) ovary.

Oophoropexy

Prophylactic oophoropexy (of the contralateral normal ovary) should be considered at the time of the surgery for detorsion of a torsed adnexa. Whether oophoropexy of the contralateral ovary can be helpful in preventing a second episode of ovarian torsion of a normal ovary needs additional evaluation, but there is no downside to performing the procedure. We offer an oophoropexy to all girls and young women who have or have had torsion of a normal ovary. If the torsion was associated and most likely due to an ovarian cyst, then an ovarian cystectomy can be performed after the detorsion and oophoropexy is not routinely offered.

If oophoropexy is elected, it can be safely accomplished by operative laparoscopy (85,86). There are varying techniques to accomplish the stabilization of the ovary. The utero-ovarian ligament can be sewn to itself to shorten the ligament, as shown in Fig. 21-16A–D, or the ovary can be sutured to the uterosacral ligament in cases where the ovary is enlarged and shortening of the utero-ovarian ligament is felt not to decrease the risk of asynchronous torsion, as shown in Fig. 21-17A–D. We perform this procedure laparoscopically and utilize a permanent nonreactive suture such as 2-0 silk. In cases of asynchronous bilateral ovarian torsion patients may elect to have bilateral oophoropexies to decrease the risk of continued episodes of torsion (Fig. 21-18A–D).

Ovarian Tumors/Neoplasms

Presentation and Examination

Patients with an ovarian tumor may present with abdominal pain or complaints of increasing abdominal girth, nausea, and vomiting, or they may be totally asymptomatic, with the mass being found on routine examination. Additionally, some patients with an ovarian tumor present with a paraneoplastic syndrome. The wide variety of symptoms caused by ovarian tumors suggests that abdominal palpation and rectal examination in the lithotomy position and a low threshold for obtaining an ultrasound evaluation are important in any girl with nonspecific abdominal or pelvic complaints (8,64). A large, thin-walled cyst may be

confused with ascites. The size of the tumor is not indicative of its malignant potential. Exquisite tenderness suggests torsion or hemorrhage of the cyst but may also occur with appendicitis and rupture.

confused with ascites. The size of the tumor is not indicative of its malignant potential. Exquisite tenderness suggests torsion or hemorrhage of the cyst but may also occur with appendicitis and rupture.

Imaging

Ultrasound is extremely helpful in the evaluation of an ovarian mass (see Chapter 23) (28,58,60,87,88,89,90,91). Ultrasound has revolutionized the management of patients with ovarian masses. Ultrasound is routinely used to determine overall size and identify whether a mass is simple, complex, solid, bilateral, or associated with free fluid (ascites). This information is helpful in forming a differential diagnosis and correlating with age, presentation, and tumor markers to determine the appropriate therapy. Ultrasound and color flow Doppler imaging appearance of an ovarian mass may help to predict malignancy in older women (92,93,94). A solid ovarian mass in childhood is always viewed as malignant until proven otherwise by surgical removal (95

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree