CHAPTER 44 Acupuncture and Herbal Treatment in Midwifery

The origin of the world is its mother;

Understand the mother and you understand the child;

Embrace the child, and you embrace the mother

Who will not perish when you die.

Acupuncture

Breech presentation

Breech presentation occurs in 2–4% of pregnant women. There are three types of breech presentation:

There are many reports from China about the efficacy of this treatment.1,2 It increases fetal activity, usually enough to turn the fetus from breech to cephalic presentation. Studies conducted in China and published in 1984 report varying success rates ranging from 89.9% to 90.3%.3

A study conducted in Italy in 1990 reports 60.6% success rate on a group of 33 women of gestational ages ranging from 30 to 38 weeks.4 A second study by the same authors presents the results of 1 week’s treatment with moxibustion in 241 pregnant women of gestational ages ranging from 28 to 34 weeks, in comparison with 264 control subjects. In the group of women treated with moxa, there were 195 versions (81%) as against 130 (49%) in the control group; the difference is statistically significant (P < 0.05). Cardini’s trial confirmed findings in the Chinese trials that the success rate is higher in multigravidae, as would be expected, owing to the reduced tone of the abdominal muscles.

A later study compared manual acupuncture to BL-67 with a control group on 67 women. The results were 76% version in the treatment group versus 45% in the control group.5 A larger randomized, controlled trial looked at 226 women with breech presentation and assigned them to either observation alone or acupuncture plus moxibustion to BL-67. The number of babies that had turned was 54% in the treatment group versus 37% in the controls.6

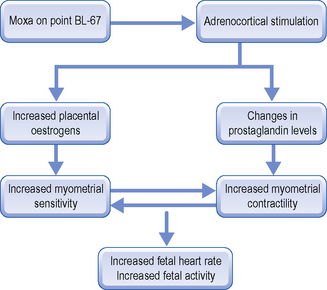

What are the mechanisms of the process? A trial carried out by the Co-operative Research Group of Moxibustion Version of Jiangxi Province postulates that the increase in adrenocortical secretion, through the resulting increase in placental oestrogens and changes in prostaglandin levels which they measured, raises basal tone and enhances uterine contractility, stimulating fetal motility, and thus making version more likely.7 This increase in fetal motility is one of the more striking features of moxibustion, perceived by almost all the women during the second half of the 15-minute treatment, and persisting even after the end of stimulation.

Figure 44.1 shows the hypothetical mechanism of the effect of moxibustion on point BL-67 Zhiyin to turn the fetus.8 As moxibustion does not involve the use of needles and needs daily applications for up to 10 days, the woman’s husband, partner or friend can be instructed in application and continue the treatment at home, with a handout covering the method and advice on safety issues regarding extinguishing of the moxa sticks.

The use of acupuncture in labour

Acupuncture for analgesia in labour

Ear points

There are a number of research trials looking at acupuncture analgesia in labour, with variable methodologies, point selections and results. One trial looked at the effect of electro-acupuncture on 168 women, using the auricular points Shenmen bilaterally, and body point L.I.-4 Hegu bilaterally for either 20 or 30 minutes.9 They found that the analgesic effect began at a mean of 40 minutes after its application, and that its duration was a mean of 6 hours. It was not necessary to use analgesic drugs of any kind on any of those who delivered during this period of time.

Origins of acupuncture treatment for delayed labour

It is said that Yu Fa Hai, an acupuncturist, came across a woman in labour when he put up for the night at an inn on his journey home. The woman happened to be the innkeeper’s wife. She had been in labour for several days, but the baby was still not born. ‘I can hasten the course of labour’, he said to her husband, and asked him to have a fat sheep slaughtered, and to make with the meat a delicious dish. Then he forced the woman to eat more than ten pieces of the mutton. Having finished eating, the woman was given acupuncture treatment. Soon the baby was born with a layer of sheep fat covering its body.10

Later, around the 5th century AD, a famous physician and acupuncturist, Xu Ben, was well known for his skill in using acupuncture on women as an oxytocic measure to expedite labour and promote a safe delivery.11

The Empress had been in a great deal of pain for several days and the baby had still not been born. Dr Li received an order to treat her as best he could. Having palpated the Empress’s pulse, he said ‘The baby’s hand has got hold of your heart, that’s why you can’t give birth to it easily.’ What should be done then? asked the Empress anxiously. Li Tong Yuan said, ‘The mother will die if the baby is saved, or the baby will die if the mother is saved.’ On hearing this, the Empress, showing the greatness of maternal love, said definitely: ‘Let the baby live, and may it bestow prosperity on the Empire in years to come.’ At her word, Dr Li Tong Yuan inserted the needle into her abdomen. The needle penetrated her heart and thrust directly toward the baby’s hand. In later life the baby became Emperor Gao Zong of the Tang Dynasty. It was said that the needle mark on the Emperor’s hand could still be seen, though faintly, on gloomy days.12

During his medical practice at Tong County, Anshi Province, Pang An Shi received a patient who was in difficult labour for seven days. All treatment applied by other doctors had failed, but at the sight of the woman, Pang An Shi said with assurance, ‘Don’t worry, you’ll be all right.’ Immediately he had the woman’s abdomen and back warmed with hot, wet towels. Then he gently massaged her abdomen. Gradually the woman became quiet. Just as she was feeling better she experienced a spasm of pain in the stomach and intestines which made her groan again. Before long, a boy was born to everyone’s joy and surprise. When asked what treatment method he applied, Pang An Shi said ‘As a matter of fact, the birth was not a difficult one. The problem was only that the baby’s hand had got hold of the mother’s intestines. I massaged the mother’s abdomen in order to find out the position of the baby’s hand. When I located it, I quickly inserted the needle at the point between the thumb and the index finger. As the hand shrank back with pain, the baby was born.’13

Acupuncture in labour: a short history

This tradition survived as late as 1970; the chapter on childbirth in the first Chinese–English edition of The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, printed in that year, mentions nothing about labour pain and gives no advice on caring for the woman during the contractions; it does, however, refer to ‘sensations’ that a woman may have once contractions begin. The manual drew on the practical expertise of local country people in the various provinces (often self-taught health workers) who went from house to house administering medical care in the form of acupuncture or herbal medicine.14

It was during this same era in Europe that interest in acupuncture analgesia for childbirth became the focus of much research by some eminent pioneers. In 1972, Christman Ehrstroem was reported to have performed the first acupuncture deliveries in Stockholm, Sweden. In 1974, Darras in France reported 20 electro-acupuncture deliveries of primiparae (first-born child) and multiparae (second or subsequent children).15

In China, Pei and Huang of the Nanjing Municipal Maternity hospital reported on a retrospective review of 200 women who had taken part in a study using acupuncture analgesia during childbirth in 1975.16

Anaesthesia for childbirth up until 1853 in England was unheard of. However, on the 7th April 1853, John Snow anaesthetized Queen Victoria when Prince Leopold was born. Simpson (a famous surgeon and obstetrician) was greatly criticised for using anaesthesia for this purpose. To prevent pain during childbirth, he was told, was contrary to religion and the express command of the scriptures. But anaesthesia had come to stay.17

Acupressure for labour

Specific actions of acupressure points used for labour are as follows:

The growing popularity of this technique is mainly due to the work by Debra Betts who, for years, has generously provided the acupressure booklet available for free download on her Web site.18. This has made acupressure accessible for countless couples, midwives and acupuncturists in an easy, concise form. She started teaching it to women in 1992. They consistently reported a reduction in their pain, combined with an overall sense of calmness and a high level of satisfaction with their birth experience. Debra has also taught acupressure to many midwives and others in venues across the UK, Europe, Canada and, of course, her native New Zealand.

It was an honour for me to help her teach it to a group of 20 Italian midwives in Milan in September 2009. I have been teaching it to couples for several years now and have been delighted with the results. We use Debra’s booklet, encouraging patients to download and print it for themselves, and I recommend her book for further details on the technique.19

Research

Since 2003, research has been published in nursing journals and all say this is a safe technique. In 2005, Ingram et al published on acupressure for induction of labour. They taught acupressure to 66 women at 40 weeks’ gestation with a control group of 76 women. The women were taught by a midwife in a 15-minute session using points G.B.-21, L.I.-4 and SP-6 and were encouraged to use the points as often as it felt comfortable. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups for the usual parameters (e.g. parity, maternal age, etc).20

A randomized controlled trial in 2004 by Lee et al looked at the effects of acupressure on labour pain and length of delivery time in 75 women using just the SP-6 point. They concluded that SP-6 acupressure was effective for decreasing labour pain and shortening the length of delivery time.21

In 2003, Chung looked at the effects of acupressure on the first stage of labour. One hundred and twenty-seven women were randomly assigned to acupressure on points L.I.-4 and BL-67 or controls. Acupressure to these points was found to lessen labour pain during the active phase of the first stage of labour.22

A systematic review by Smith and Cochrane included three trials on acupuncture for pain management in labour, and concluded that evidence from the trials suggested women receiving acupuncture required less analgesia, including the need for epidurals. The results also suggested a reduced need for augmentation with oxytocin.23

The largest randomized controlled trial to date was conducted in Denmark with 607 women in labour at term who received acupuncture to individualized points, TENS or traditional analgesic drugs. The use of pharmaceutical and invasive methods was significantly lower in the acupuncture group (P < 0.001).24

Acupuncture in the treatment of difficult labour

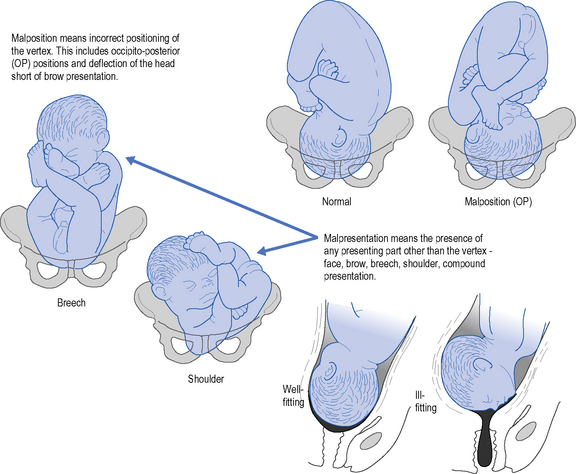

Difficult labour may result from abnormality of the uterine contractions, cephalo-pelvic disproportion (i.e. imbalance between the size of the maternal pelvis and the fetal head) or malposition of the baby. Acupuncture can be of help in the first of these, but not for the others. It is important to note that ‘malposition’ of the baby should not be confused with ‘malpresentation’, i.e. when the baby’s bottom (breech), face or brow presents first as opposed to head, as in normal cephalic presentation. ‘Malposition’ means incorrect positioning of the head, which includes occipito-posterior position and deflection of the head (short of brow presentation). ‘Malpresentation’ occurs when various presenting parts other than the head show first, i.e. face, brow, breech (bottom) or shoulder (see Fig. 44.2).

Figure 44.2 Malposition and malpresentation.

(Reproduced with kind permission from AWF Miller and R Callander 1994 Obstetrics Illustrated, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, p. 296.)

The ABC of Acupuncture (Jia Yi Jing, AD 282) states: “In prolonged labour and retained placenta use Kunlun [BL-60]”.25 Various research studies have explored acupuncture’s ability to initiate contractions prior to rupture of the membranes, and prior to the woman experiencing any labour pains.26 The acupuncture points which may be used vary according to the situation. In a straightforward case of ruptured membranes in a fit and healthy woman, with no contractions, such a treatment as the following may be used:

Identification of patterns and treatment for difficult labour

There are two primary causes of delayed or difficult labour in Chinese medicine:

Deficiency of Qi and Blood

Stagnation of Qi and Blood

Clinical manifestations

This is often seen when the woman has a lot of fear and tension before labour.

Acupuncture

Explanation

Ancient acupuncture prescriptions for difficult labour28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree