Acne and Other Disorders of the Pilosebaceous Unit

Sara W. Dill and Bari B. Cunningham

ACNE VULGARIS

Acne vulgaris is one of the most common cutaneous disorders and occurs in more than 85% of individuals between the ages of 12 to 24 years.1 The onset of clinical disease usually occurs between the ages of 12 and 14 years, but mild disease may develop as early as 7 to 8 years of age and tends to occur somewhat earlier in girls than in boys. This prepubertal acne may be the first sign of pubertal maturation. Acne in this group is primarily comedonal and midfacial, favoring the forehead, nose, medial cheeks, and chin.2 Acne generally resolves in the late teens or early 20s. Although most acne may be thought of as physiologic, disease with unusual features such as early onset or severe recalcitrance to therapy warrants evaluation for underlying abnormalities of the adrenal or ovarian systems.

Acne is most commonly localized to areas of highest sebaceous gland concentration and activity, such as the face, chest, and upper back. Acne is a multifactorial disease, involving excessive or increased sebum production, abnormal epithelial cell proliferation and desquamation, microbial proliferation, and inflammation.3 Acne lesions begin with the development of the microcomedone, a small cyst plugged by accumulated sebum, desquamated epithelial cells, vellus hairs, and bacteria. The formation of closed comedones (whiteheads) and open comedones (blackheads) is initiated by abnormal cornification of the follicular orifice (Fig. 365-1).

Inflammatory lesions (ie, papules, pustules, or nodules) develop when the intradermal wall of the comedone ruptures, releasing comedonal contents into the dermis and provoking an intense, suppurative, and later a foreign-body, granulomatous-type inflammatory reaction. In cystic acne, the inflammatory reaction is extreme, resulting in deep nodules, sinus tracts, and cysts.

FIGURE 365-1. Comendonal acne with many open and closed comedones and a mild inflammatory component.

The surge of androgen production that occurs in adolescence leads to increased sebum production which serves as a substrate for Propionibacterium acnes. Bacterial lipases liberate free fatty acids from sebum; these lipids in turn may stimulate follicular hyperkeratosis. Other bacterial products act as irritants and as chemotactic factors that recruit neutrophils.1 The severity of acne appears to be genetically determined. Increased delayed hypersensitivity to P acnes has been noted in patients with severe forms of acne.

The goal of acne therapy is to minimize scarring and to alleviate the psychologic distress of a disfiguring skin condition during critical years of social and sexual development. Therapy is directed toward correcting abnormal follicular keratinization, and decreasing the population of P acnes, sebum production, and inflammation (eTable 365.1  ). Treatment must be individualized and should be based on the severity of disease, the types of lesions, and the patient’s motivation.8

). Treatment must be individualized and should be based on the severity of disease, the types of lesions, and the patient’s motivation.8

The majority of patients can be treated with topical medications of three types: benzoyl peroxide products, antibiotics, and retinoids.7 Each has distinct advantages, and concurrent use of these agents may have synergistic effects. Benzoyl peroxide has both bactericidal and mild comedolytic activities.1 It is available in cream, gel, lotion, and wash forms, in concentrations from 2.5% to 20.0%. Irritation evidenced by erythema and scaling is the most significant side effect; skin and hair hypopigmentation and bleaching of clothing and towels may also occur. Benzoyl peroxide is particularly useful because of its bactericidal nature, and frequent use inhibits the development of bacterial resistance, a growing problem.10

Topical retinoids (tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene) normalize keratinocyte differentiation, decreasing the “stickiness” of the epidermal cells lining the follicular lumen.  Tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene are available in creams and gels of varying concentrations. All forms should be introduced gradually to decrease the likelihood of adverse effects such as drying, irritation, or sun sensitivity. Daily therapy can usually be tolerated after several weeks; these agents are generally not used more than once a day.

Tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene are available in creams and gels of varying concentrations. All forms should be introduced gradually to decrease the likelihood of adverse effects such as drying, irritation, or sun sensitivity. Daily therapy can usually be tolerated after several weeks; these agents are generally not used more than once a day.

Topical antibiotics including 2% erythromycin or 1% clindamycin may be used in patients with an inflammatory component to their acne.  The concurrent use of topical benzoyl peroxide has been shown to inhibit and decrease resistance. Compliance and efficacy may be enhanced by the use of combination topical agents of benzoyl peroxide gel plus either clindamycin or erythromycin. These agents are also effective in decreasing the emergence of resistant strains of Propionibacterium acnes.1

The concurrent use of topical benzoyl peroxide has been shown to inhibit and decrease resistance. Compliance and efficacy may be enhanced by the use of combination topical agents of benzoyl peroxide gel plus either clindamycin or erythromycin. These agents are also effective in decreasing the emergence of resistant strains of Propionibacterium acnes.1

Adolescents who do not respond to topical therapy or who present with a moderate to severe inflammatory form of the disease require systemic antibiotics. Tetracycline (usually 500 mg bid) has been frequently prescribed because of its safety and efficacy. However, compliance may be suboptimal because the drug cannot be taken with dairy products or iron-containing foods and requires twice-a-day dosing. Doxycycline (50–100 mg bid) is often better tolerated and is more lipophilic but is more likely to induce photosensitivity. Minocycline (usually 50–100 mg bid) may be more efficacious for some patients. Rare cases of hypersensitivity and lupus-like reactions, along with increased cost and a rare risk of blue-gray skin discoloration, argue for its use as second-rather than first-line therapy. Alternative antibiotics for effective treatment of acne include azithromycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and the cephalosporins.10 Topical therapy should be used concurrently with any oral antibiotic, and the oral antibiotic should be slowly tapered once significant improvement has been achieved (usually 3–6 months).1

An additional treatment option in girls with moderate to severe or persistent inflammatory acne is hormonal therapy. This may be particularly effective in girls with premenstrual flaring of their acne. There are currently several oral contraceptive pills that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of acne.7

Oral isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) is a highly effective oral agent for the treatment of acne, but its expense and transient but significant side effects limit its use to patients who have scarring nodulocystic acne or fail to respond to an adequate trial of conventional therapy, who understand its side effects, and who can comply with the necessary restrictions and mandatory registration in the iPLEDGE risk management program. Because of the teratogenic effects of isotretinoin, drug manufacturers and the FDA have approved a new isotretinoin risk management program called iPLEDGE. All patients, prescribers, pharmacies, manufacturers, and drug wholesalers are required to register with this program. See www.ipledgeprogram.com for more information.

NEONATAL AND INFANTILE ACNE

NEONATAL AND INFANTILE ACNE

Acne may be present at birth or may develop during the newborn period. The lesions are most often superficial and are usually confined to the face and upper trunk. Neonatal acne appears to result from the stimulating effect of maternal and fetal androgens on the newborn’s sebaceous glands. Several studies have implicated pityrosporum (Malassezia) as a possible etiologic agent for some cases of neonatal acne. Complete clearing of the disease occurs within a period of 1 to 3 months.2 When acne develops later in infancy, topical agents may prove effective, but infants with more severe inflammatory disease, including cystic acne, may require systemic erythromycin, isotretinoin, or even intralesional or systemic corticosteroids.2 Unusually persistent or severe infantile acne may be indicative of abnormal androgen or cortisol production, and a complete endocrinologic workup should be considered.2

SEBACEOUS GLAND HYPERPLASIA AND MILIA

Hypertrophic sebaceous glands are typically seen on the nose of full-term newborns as multiple pinpoint pale yellow-white papules. They may also be noted on the forehead, cheeks and upper lip. The condition resolves with decreasing maternal androgen levels during the first weeks of life and does not require any treatment.20

Milia are tiny epidermal cysts usually derived from a vellus hair follicle. These 1- to 3-millimeter white keratinous cysts are most commonly seen on the face of full-term newborns but may be seen on other areas. If persistent or widespread, milia can be a sign of other disorders, including dystrophic scarring forms of epidermolysis bullosa, hereditary trichodysplasia (Marie-Unna hypotrichosis), or the oral-facial-digital syndrome type 1.20 Milia may also occur in children and adolescents, especially around the eyes as well as along the nasal crease in children with allergic rhinitis. These nasal crease milia may rupture and become inflamed, producing a clinical picture known as “pseudoacne.”21 Milia usually disappear without treatment within a few weeks in newborns, but may require treatment with topical retinoids and/or manual extraction when seen in children and adolescents.

HIDRADENITIS SUPPURATIVA

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic, inflammatory disease of the apocrine gland–bearing areas of the body and typically involves the axilla, inguinal creases, perineum, and areolae. Although children as young as 4 or 5 years may be affected, most cases begin during puberty. The condition is more common in women and in blacks. Initially, one or more tender cysts may be present in the axillae or in the inguinal area. These are easily mistaken for furuncles, but the recurrent nature of the condition and negative or mixed bacterial cultures eventually make the diagnosis obvious. In mild cases, the cysts resolve spontaneously or after drainage, and only an occasional new lesion develops. In severe cases, more and more cysts develop, suppurate, rupture, and scar, leaving sinus tracts and fistulas admixed with new inflammatory lesions.

Treatment of mild cases includes topical antibacterial agents such as clindamycin and/or benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, tetracyclines), incision and drainage of fluctuant cysts, and intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide (5–10 mg/mL) to inflamed areas.22 In some instances, systemic corticosteroids may be necessary. Isotretinoin (1 mg/kg/day) is helpful in some cases, but it is usually less effective than in cystic acne.22 Dapsone has been reported to be effective in some cases and is a reasonable therapeutic alternative for difficult to manage disease.22 New immunosuppressive medications, including infliximab and etanercept, show some promise as alternative treatments for severe disease.22 In severe or recalcitrant cases, surgical excision of the apocrine glands is still the preferred treatment, although recurrences are not uncommon.23

ALOPECIA

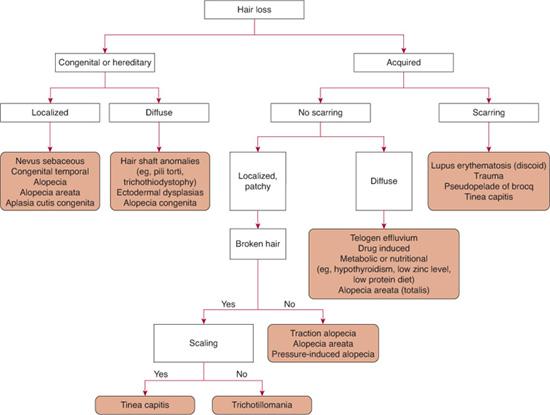

Hair is a nonliving biologic fiber found everywhere on the human body surface, with the exception of the palms, soles, glans penis, and lateral digits. Deficient hair growth is known as hypotrichosis, whereas hair loss is termed alopecia. Alopecia is subclassified as scarring or nonscarring, based on the loss or preservation of the hair follicle, respectively, and as generalized or localized (Fig. 365-2).24 In addition, there are hair shaft abnormalities that may cause breakage or hair loss secondary to hair fragility. Tinea capitis, the most common cause of hair loss in children, should be considered in any pediatric patient who presents with scaling hair loss.

LOCALIZED NONSCARRING ALOPECIA

LOCALIZED NONSCARRING ALOPECIA

Alopecia areata is a common, idiopathic disorder characterized by the sudden appearance of round or oval patches of hair loss on the scalp and other body sites. The condition may have its onset as early as birth but usually appears in school-age children.25 Its occasional association with autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto thyroiditis, myasthenia gravis, diabetes, and vitiligo has suggested an autoimmune process. Other associations include trisomy 21, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, adrenal disease, and atopy.24

The typical lesion of alopecia areata is a smooth, shiny, hairless, round patch of the scalp that appears suddenly over the course of several days. Scattered long hairs within the bald area or “exclamation point hairs” (hairs with a narrowed proximal diameter and often shorter length and lighter color) may be detected. Often the nails are affected with pits and grooves giving a “Scotch plaid” appearance.25

Two clinical forms of alopecia areata occur: patchy alopecia areata and alopecia totalis or universalis. In the former, a few or many patches of hair are lost and the prognosis for regrowth, either spontaneously or with treatment, is good. If patches coalesce into large areas with loss of more than 50% of scalp hair, the prognosis is generally less favorable. The presence of alopecia totalis (loss of all scalp hair) or alopecia universalis (loss of all body and scalp hair) is a poor prognostic sign, especially in children. Such hair loss responds poorly to treatment, and even if hair regrows completely, recurrent episodes of alopecia totalis are likely.

The diagnosis of alopecia areata is usually made clinically but can be confirmed with a scalp biopsy in atypical cases.

Therapy for alopecia areata usually consists of topical or intralesional corticosteroids. Localized, mild disease often responds to potent (class I or II) topical corticosteroid therapy.

Treatment of the pediatric patient with alopecia areata should address the emotional needs of these children and their families. Patients with widespread, long-standing alopecia areata may experience social stigmatization and may benefit from hair prostheses.

Trichotillomania is characterized by compulsive pulling, twisting, or breaking of hair. Affected areas of the scalp demonstrate irregularly shaped areas of partial alopecia with broken hairs of varying lengths, giving the scalp a “moth-eaten” appearance. A fringe of hair in the frontal area is usually left intact, as are more inaccessible or painful parts of the occipital scalp.26 The eyebrows or eyelashes may be pulled out instead of or in addition to scalp hair. Trichotillomania may be a nervous habit analogous to nail biting in some cases but can also indicate serious psychopathology, particularly in older children.

Direct confrontation and accusation are rarely helpful. Rather than querying the patients as to whether they are engaging in hair pulling, it is helpful to ask them when they are pulling their hair. In addition, using the analogy to nail biting may make a frank discussion of the problem more acceptable. Behavioral modification techniques such as habit reversal or psychiatric evaluation should be undertaken if the problem does not resolve or if other psychiatric symptoms are present.26

Tension or pressure on the scalp can cause hair breakage or loss, and children seem to be particularly susceptible to this problem. Traction alopecia is fairly common in young girls who have tight ponytails or braids. Hair thinning occurs at the scalp margin, especially in temporal areas. Folliculitis may also be present. The problem is most common in African American girls, often exacerbated by trichorrhexis nodosa. If hair-styling techniques are not changed, permanent hair loss can result.24 Traumatic alopecia can result from prolonged pressure on the scalp as might occur with general anesthesia, usually near the vertex of the scalp. A “halo” of pressure alopecia can also be seen after delivery in an area corresponding to the caput succedaneum. Infants, especially those with atopic dermatitis, are particularly susceptible to frictional hair loss and may lose large areas of occipital and parietal scalp hair from rubbing the head against the bed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree