Obstetrical care in the United States is unnecessarily costly. Birth is 1 of the most common reasons for healthcare use in the United States and 1 of the top expenditures for payers every year. However, compared with other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, the United States spends substantially more money per birth without better outcomes. Our team at the Clinical Excellence Research Center, a center that is focused on improving value in healthcare, spent a year studying ways in which obstetrical care in the United States can deliver better outcomes at a lower cost. After a thoughtful discovery process, we identified ways that obstetrical care could be delivered with higher value. In this article, we recommend 3 redesign steps that foster the delivery of higher-value maternity care: (1) to provide long-acting reversible contraception immediately after birth, (2) to tailor prenatal care according to women’s unique medical and psychosocial needs by offering more efficient models such as fewer in-person visits or group care, and (3) to create hospital-affiliated integrated outpatient birth centers as the planned place of birth for low-risk women. For each step, we discuss the redesign concept, current barriers and implementation solutions, and our estimation of potential cost-savings to the United States at scale. We estimate that, if this model were adopted nationally, annual US healthcare spending on obstetrical care would decline by as much as 28%.

THE PROBLEM: US healthcare spending is outpacing average gross domestic product growth rates, which is a national crisis that is diverting spending on other vital aspects of our economy. Pregnancy and birth are among the most frequent reasons for hospitalization in the United States, thereby contributing to the increase in US healthcare spending. New care models are needed within obstetrics to reduce spending safely.

A SOLUTION: Stakeholders must redesign delivery of obstetrical care to optimize outcomes at the lowest reasonable cost. Three evidence-based solutions can be implemented at provider, group practice, and system levels to decrease the average cost per capita safely without adversely affecting outcomes.

Core Recommendations

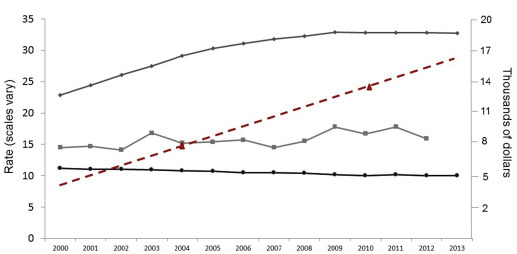

Healthcare spending in the United States (US) is rising rapidly and is recognized as a national crisis. For the past 15 years, payments that are associated with childbirth have increased without significant improvements in national perinatal outcomes ( Figure 1 ). Approaching 4 million deliveries per year, birth is one of the most common reasons for hospital use in the US and is a top expenditure for payers. From 2004–2010, commercial payments for maternity care increased by >50%, with out-of-pocket expenses borne by families increasing 4-fold. Annual payments that are associated with pregnancy, birth, and postpartum care that include both term and preterm newborn infants are approximately $87 billion.

In the past, addressing costs of care delivery has not been a priority in obstetrics. Now, it is imperative that, as providers in a system plagued by escalating spending, we consider how we can deliver quality care at a more sustainable cost. Obstetrics has already demonstrated that practice can change safely at a system level to improve quality, most notably with recent success in the prevention of early elective delivery. A series of articles by Lagrew and Jenkins described the changing US obstetrical care environment and suggested several categories in which transformational change could be made to improve value in obstetrics. Building off this series, we focused on solutions within one of these categories: care system reform.

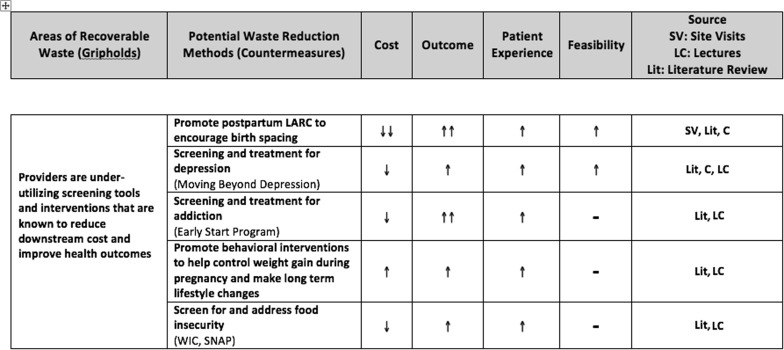

Our discovery process at the Clinical Excellence Research Center, described previously, began with comprehensive data gathering that consisted of 4 components: (1) comprehensive literature review focused on comparative cost-effectiveness, (2) clinical site observations to uncover opportunities for value improvement, (3) discussions with experts and innovators in healthcare value, and (4) calculations of estimated national savings with the use of available payment data. Available cost data in the obstetrical setting is limited, but every effort was made to estimate costs and potential savings reasonably ( Supplemental Tables 1-4 ). From these discovery processes, the top areas of expenditure were identified. In our search, the top identified areas included US hospitalization costs for live birth, total cost of cesarean deliveries, costs of preterm deliveries, and maternal obesity. These top areas of expenditure were then categorized into areas of “recoverable waste.” Next, potential waste reduction methods were identified. Each potential waste reduction method was rated on its effect on cost, clinical outcomes, patient experience, and feasibility of implementation ( Figure 2 ). We refined a composite of care delivery strategies with the participation of expert advisors that included clinicians, social scientists, health services researchers, and business leaders. Over the course of this refinement process, we identified 3 changes that could lead to a fundamental redesign for highest-value obstetrical care. We present these changes as steps that can be executed at the provider, group practice, and system levels. If implemented broadly in the US, we estimate that these changes could reduce national spending on maternity care by as much as 28%.

Recommendation 1: Provide timely postpartum contraception

A simple provider-driven change can reduce poor outcomes and excess costs that are related to unplanned and closely spaced births. Approximately 30% of women in the US become pregnant within 1 year after giving birth, and 50% of all pregnancies in the US are unplanned. Unplanned pregnancies are associated with increased risk of poor outcomes, which include preterm birth, congenital defects and child abuse, although short-interval pregnancies are associated with significantly higher rates of adverse outcomes like preterm birth. These factors add substantial costs to each birth and subsequent neonatal and pediatric care. The March of Dimes estimates each preterm birth raises perinatal care costs by an average of $58,917 for commercially insured women and infants (2013 $US).

We recommend that all providers routinely offer immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) to all appropriate candidates. LARC devices are well-recognized to be among the most effective methods of birth control, yet 1 study reported that 60% of women who requested LARC after pregnancy did not receive it. Many women, including up to 55% of those insured by Medicaid, do not attend their postpartum visit, when most providers plan for LARC insertion.

Immediate postpartum LARC would help reduce both unplanned repeat pregnancies and the high rate of costly complications that are associated with short-interval pregnancies. A robust prenatal contraception curriculum will allow women to consider and select this option. This expanded shared decision-making process need not overburden prenatal-care providers but could be delivered via online contact, mobile applications, or other education innovations.

Two barriers currently exist to broad implementation of immediate postpartum LARC provision. First, many providers believe that the higher intrauterine device expulsion rate after postplacental insertion means this strategy will not be cost-efficient. Although it is true that the expulsion rate is higher compared with placement at the postpartum visit, a decision-analysis model developed by Washington et al demonstrated that it is still a cost-saving strategy to replace a woman’s intrauterine device if it is expelled compared with waiting to provide her with an intrauterine device at the postpartum visit. Second, most payers reimburse only for placement of the device at the postpartum visit, but not during the birth episode in the hospital. However, forward-thinking systems are addressing this problem. In 2012, South Carolina became the first state in the country to pay Medicaid providers for LARC insertion before discharge. The associated Choose Well Initiative published a toolkit that details how to overcome the barriers that currently exist to providing women with LARC immediately on delivery. Furthermore, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends providing LARC at time of delivery. Provider incentive models most likely to increase provision of immediate postpartum LARC provision may include performance profiling and peer review, feedback regarding their own patients’ LARC use at 12 months after insertion, technical assistance during implementation, and the reduction of administrative requirements.

From a national annual spending perspective, we estimate that, if immediate postpartum LARC were available nationally to all women, approximately 33% of women would select it. Fewer unplanned short-interval pregnancies in the US could result in a 14% reduction of national annual spending on maternity care ( Supplementary Table 1 ).

Recommendation 2: Tailor prenatal care to the needs of individual patients

Women with psychosocial/sociodemographic risk factors

Group prenatal care has been shown to improve birth outcomes, specifically preterm birth rates, and to decrease obstetrical spending for distinct populations of women with known risk factors. Examples of such risk factors include depression or anxiety, substance abuse, underweight/food insecurity, young age, and African American race. Studies that have demonstrated positive effects have recruited women with the highest risk of poor perinatal outcomes. At a group practice level, we assert that women should be screened for these risk factors and offered group prenatal care if they meet screening criteria.

In group prenatal care, 8–12 pregnant women at similar gestational ages attend prenatal visits together and engage in educational activities, which are led by a consistent provider. Group care reduces preterm birth rates and neonatal intensive care unit stays in high-risk populations. A recent 5-year retrospective cohort study of Medicaid-insured women in South Carolina examined the outcomes and costs of women involved in group prenatal care compared with those who received individual prenatal care. The study authors modeled the differences in adverse birth outcomes between groups and found that women who received group care had a reduced risk of (1) premature birth by 36%, (2) low-birthweight by 44%, and (3) neonatal intensive care unit stay by 28%. For each of these adverse outcomes prevented, approximately $25,000 in newborn care payments were averted.

This analysis of the economic impact of group prenatal care was retrospective, and prospective cost studies of large-scale implementation are needed. However, the potential savings are significant. We calculate that broadly implementing group prenatal care for women at high risk of preterm birth could reduce maternal and neonatal payments that are associated with preterm birth by 10–25% in the US, depending on insurance type and extent of uptake, which represents approximately 2% of total US maternity healthcare spending ( Supplemental Table 2 ).

Obstetric providers have been slow to adopt group care in the face of implementation challenges such as organizing new appointment scheduling procedures and work flows, locating space that will accommodate a group, and acquiring facilitation skills. However, prenatal care providers who meet these challenges can deliver substantial cost-savings and improve patient outcomes, experience, and satisfaction.

Women with low medical risk and minimal social stressors

Many studies have demonstrated that healthy pregnant women in developed countries can attend fewer prenatal visits without adverse maternal outcomes. Based on these findings, we propose that low-risk women in the US can attend a targeted schedule of 9 total visits safely. In fact, in almost all cases, there is no need for an in-person visit in close proximity to routine obstetric ultrasound examinations. Although studies show that women value personal connection with their providers, these relationships can be maintained with the use of telehealth options, such as apps or mobile platforms, that allow women with fewer in-person visits to be satisfied equally with their care. In a recent analysis of prenatal costs and resource use, a modified prenatal visit schedule saved $499 or 75 minutes of clinical time per pregnancy, which allowed providers more time for other tasks such as caring for high-risk patients. Pregnant patients would reduce the time they must miss work and save money on child care and transportation. Broadly implementing a reduced prenatal visit schedule for appropriate women could reduce the costs that are related to prenatal care delivery in the US by 2.5–13%, depending on the intensity of supplemental telehealth used ( Supplemental Table 3 ).

Recommendation 3: Create safe outpatient birth centers within integrated delivery systems

From a system level perspective, we propose a nation-wide network of hospital-affiliated outpatient birth centers (OBCs), which described in detail elsewhere, that could improve the experience, quality, and cost of care for appropriately risk-stratified pregnant women.

For most women, the greatest expense during pregnancy is the actual birth episode. In 2010, the average commercial and Medicaid payments for vaginal births were $14,857 and $6361, respectively. Most of the payment (59%) was for hospital fees. However, many low-risk women ultimately do not need all the services that the hospital offers, despite paying the high facility fees. In fact, some data suggest that just being in a hospital increases the chance that women will receive a procedure, such as a cesarean delivery. Low-risk women could deliver in hospital-affiliated OBCs instead, which can provide excellent patient experience and clinical outcomes at a lower cost.

Current birth centers in the US vary substantially in their integration with hospitals and health systems, accreditation, and provider licensure. This variation can lead to inconsistent and even adverse outcomes. However, in countries where birth centers are an integrated part of maternity services, such as the United Kingdom, they provide equivalent or better maternal and neonatal outcomes in low-risk populations.

Our proposed hospital-affiliated OBCs for low-risk pregnant women could mitigate the concerns regarding variation in integration, accreditation, and standards that are associated with some US birth centers. OBCs would be integrated with and adjacent to high-volume consulting hospitals. Women would be eligible to birth in these centers after careful screening with the use of strict eligibility criteria for low-risk births. Adjacency to a collaborating hospital would enable rapid transport to the labor and delivery unit with the use of standardized best-practice protocols and appropriate treatment in emergencies. OBCs would also be required to receive accreditation to ensure standardization. These centers would benefit from the resources and culture of an integrated healthcare system, such as immediate availability of necessary providers and facilities, excellent communication, and close working relationships. As such, we expect that the OBC safety standards would at least match that of current hospitals.

With careful attention to patient screening, comprehensive guidelines for transfer to higher acuity sites, and streamlined communication across birth settings, we assert that 40% of all US women could deliver in OBCs; this number is consistent with population risk estimates and birth setting recommendations that were published by the National Institute for Health Care Excellence in the United Kingdom. To date, there are no well-done perspective US trials that are comparing the cost of care that is initiated through birth centers compared with hospital-based care. However, if OBCs were created on a national scale, we calculate that the reduction in payments that are associated with vaginal births and the reduction in the cesarean delivery rate would result in a 12% reduction in total US maternity care spending ( Supplemental Table 4 ).

Multiple maternity care professional organizations that include the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology endorse birth centers as safe settings for low-risk women to deliver. When hospitals and their providers fulfill their professional duties owed to the patient at the time of presentation, they minimize their risk for punitive malpractice judgments for “breach of duty” (personal communication, David Pulley, VP One Beacon Insurance Group, June 9, 2016). Although providers and facilities may fear an increased risk of more frequent or expensive malpractice claims if they are connected to a birth center, there is no evidence to support this concern.

Recent Progress

The Institute of Medicine declared it a “Healthcare Imperative” to decrease the per-capita cost of care while delivering best practices. We have outlined 3 maternity care innovations that can be implemented at specific organizational levels inside a healthcare system. If effectively introduced on a broad scale, these solutions have the potential to increase the value of US obstetrical care by improving outcomes and experience while safely reducing costs. By reducing the annual cost of perinatal care by 28%, these changes potentially could reduce total annual US healthcare spending by 1%.

Supplemental Tables

The following Tables represent projections for how full, national implementation of changes in the maternity care system might reduce total annual payments that are associated with pregnancy, birth, the postpartum period, and care for preterm neonates through the first year of life. We used publicly available payment data from available sources, which are cited.

| Variable | Status quo | Model change a |

|---|---|---|

| Annual births (2014) | 3,985,924 b | 3,985,924 |

| Women who give birth in the United States each year who get pregnant again within 12 months: short-interpregnancy interval, n (%) | 1,195,777 (30) c | 636,751 (16) d |

| Of those who give birth and experience short-interpregnancy interval repeat pregnancy, 65% e experience a live birth, n | 777,255 | |

| Of those women who give birth and experience short-interpregnancy interval repeat pregnancy, 35% experience an abortion: spontaneous or therapeutic, n | 418,522 | |

| Preterm birth rate, 2014, all births, % | 9.57 b | |

| Annual preterm births with the use of 2014 total births multiplied by the 2014 preterm birth rate | 381,453 | |

| Preterm birth rate in pregnancies with short-interconception interval, % | 26 f | |

| Annual preterm births among women with short-interpregnancy interval, n | 202,086 | |

| Average additional payments associated with preterm birth, both mother and infant (50% each Medicaid and commercial payers), n | 44,777 | |

| Women who desire immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception, n (%) | 1,315,355 (33) g | |

| Women who desire any postpartum long-acting reversible contraception but do not receive it, n (%) | 789,213 (60) h | |

| Women who desire immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception and receive it, including the 19% i who expel an intrauterine device and need it replaced at postpartum office visit | Unknown | |

| Pregnancy rate for all hetero, partnered women who are not contracepting (rate unknown in immediate postpartum women), % | 85 j | 85 |

| Number of pregnancies among women during the first 12 months after delivery who wanted postpartum long-acting reversible contraception but did not get it, n | 670,831 | 111,805 |

| Averted pregnancies in this group, n | 559,026 | |

| Pregnancies in this group that result in live birth, % | 65 | 65 |

| These pregnancies that result in live birth, n | 436,040 | 72,673 |

| Pregnancies that would have resulted in live births if no access to immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception was available (in other words, averted short-interval pregnancies during the first year after delivery that would have resulted in live births, n | 363,367 | |

| Number of averted short-interval births that would have been preterm (assuming preterm birth rate of 26%), n | 94,475 | |

| Average payments per birth, 2010 USD (2013 $US) | 16,200 k | |

| Averted payments (average) for maternity care due to averted closely-spaced pregnancies this year, 2013 $US | 5,886,548,763 | |

| Average additional commercial payments for both mother (time of birth) and infant (birth to 1 year) associated with preterm birth, exceeding the average payments made for full-term births, 2013 $US | 58,917 l | |

| Average additional Medicaid payments for both mother (time of birth) and infant (birth to 1 year) associated with preterm birth, exceeding the average payments made for full-term births, 2013 $US | 29459 m | |

| Averted additional payments (average) for preterm births due to averted closely-spaced pregnancies this year, 2013 $US | 4,174,653,904 | |

| Total averted payments related to both maternity care and additional payments for preterm births, 2013 $US | 10,061,202,666 | |

| Cost of long-acting reversible contraception devices, including intrauterine devices and implants: 1 unit, 2016 $US | 600 n | |

| Cost of long-acting reversible contraception device, total, including 19% replacement, a $ | 469,581,706 | |

| Savings: all averted payments minus cost of long-acting reversible contraception, 2013 $US | 9,591,620,960 | |

| Total savings using denominator $81,652,329,009, o % | 11.75 |

a Assumptions in this scenario

b Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: Preliminary Data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol. 64, no. 12. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2015

c Copen CE, Thoma ME, Kirmeyer S. Interpregnancy intervals in the United States: data from the birth certificate and the national survey of family growth. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2015;64:1-11

d This would be the new rate of short interpregnancy interval after national implementation of immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception provision, using the assumptions set forth in this Table

e Ventura SJ, Curtin SC, Abma JC, Henshaw SK. Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the United States, 1990–2008. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol. 60, no. 7. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2012

f DeFranco EA, Ehrlich S, Muglia LJ. Influence of interpregnancy interval on birth timing. BJOG 2014;121:1633-40

g Dahlke JD, Ramseyer AM, Terpstra ER, Doherty DA, Keeler SM, Magann EF. Postpartum use of long-acting reversible contraception in a military treatment facility. J Womens Health 2012;21:388-92

h Ogburn JAT, Espey E, Stonehocker J. Barriers to intrauterine device insertion in postpartum women. Contraception 2005;72:426-9

i We assumed a 19% expulsion rate; the expulsion range is wide: 2.4-37%, cited in Kapp N, Curtis KM. Intrauterine device insertion during the postpartum period: a systematic review. Contraception 2009;80:327-36

j Because the rate of spontaneous pregnancy under the circumstances that is specific to the first year after delivery in the absence of a birth control method (other than lactational amenorrhea) is unknown, we assumed an 85% pregnancy rate during a year of unprotected sex, as suggested in Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397-404

k Using the average 2010 payments for the pregnancy-birth episode (reported in Truven Marketscan Health Analytics. The cost of having a baby in the United States. January 2013. Prepared for: Childbirth Connect, Catalyst for Payment Reform, Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform) and assuming 50% of births are paid by Medicaid and 50% are paid by Commercial payers, and using the 2014 cesarean birth rate of 32.2%

l March of Dimes. Premature birth The financial impact on business Employer expenditures and healthcare utilization figures from Truven Health Analytics, Inc. Costs of Preterm Birth. Prepared for March of Dimes, 2013. Available at: http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/premature-birth-the-financial-impact-on-business.pdf . Accessed: 12 September 2016

m Gareau S, Lòpez-De Fede A, Loudermilk BL, et al (Group prenatal care results in Medicaid savings with better outcomes: a propensity score analysis of centeringpregnancy participation in South Carolina. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:1384-93) estimated that for every preterm birth averted, approximately $25,000 US are not spend on neonatal care, not counting additional maternal payments that are associated with preterm birth that are averted. This number is one-half of the March of Dimes 2013 report of the additional cost to employers for each preterm birth (additional newborn and maternal payments)

n Intrauterine devices and implants a guide to reimbursement. Available at: larcprogram.ucsf.edu . Accessed: September 13, 2016

o We calculated this denominator using the annual births per year in 2014, the average costs of the preganancy episode according to Truven Marketscan Health Analytics (The cost of having a baby in the United States. January 2013. Prepared for: Childbirth Connect, Catalyst for Payment Reform, Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform), the preterm birth rate as of 2015, and the approximate total annual payments for additional care of preterm infants during the first year of life. Available at: http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Cost-of-Having-a-Baby1.pdf . Accessed February 4, 2017.

| Variable | Status quo | Model |

|---|---|---|

| US births per year, n | 3,985,924 a | 3,985,924 |

| Psychosocial stressor prevalence, % | 50 b | 50 |

| Births to women without high psychosocial stressors (normal stress), n | 1,992,962 | 1,992,962 |

| Births to women with psychosocial risk factors for preterm birth (social stress), n | 1,992,962 | 1,992,962 |

| Model effect, Percentage reduction in number of preterm births | 0.33 c | |

| Preterm birth rate, % | ||

| Among women without high psycho-social stressors (“normal stress”) | 9.6 d | 9.6 |

| Among women high psycho-social risk factors (“social stress”) | 13.0 e | 8.7 f |

| Preterm births, n | ||

| Normal stress | 191,324 | 191,324 |

| Social stress | 259,085 | 173,587 |

| Preterm births in this high-risk group | 259,085 | 173,587 |

| Decrease in preterm births | — | 85,498 |

| Preterm births associated with increased stressors, by payer, % | ||

| Medicaid | 75 g | 75 |

| Commercial | 25 g | 25 |

| Preterm births, n | ||

| Medicaid normal stress | 143,493 | 143,493 |

| Commercial normal stress | 47,831 | 47,831 |

| Medicaid social stress | 194,314 | 130,190 |

| Commercial social stress | 64,771 | 43,397 |

| Preterm birth payments (birth to 1 year), 2013 $US | ||

| Commercial | 58,917 h | 58,917 |

| Medicaid | 29,459 i | 29,459 |

| Total payments related to preterm birth, 2013 $US | ||

| Medicaid normal stress | 4,227,096,318 | 4,227,096,318 |

| Commercial normal stress | 2,818,064,212 | 2,818,064,212 |

| Medicaid social stress | 5,724,192,930 | 3,835,209,263 |

| Commercial social stress | 3,816,128,620 | 2,556,806,175 |

| Total payments, 2013 $US | 16,585,482,079 | 13,437,175,968 |

a Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: Preliminary Data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol. 64, no. 12. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015

b Assuming that about 50% of women have psychosocial risk factors such as young age, depression and/or anxiety, or poverty

c Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al (Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:330-9) report a preterm birth rate reduction of 33% among women <25 years old in publicly funded prenatal clinics

d March of Dimes, 2015. Premature birth report card. Available at: http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/premature-birth-report-card-united-states.pdf . Accessed: September 12, 2016

e Extrapolated from reported preterm birth rates in: Venkatesh KK, Riley L, Castro VM, Perlis RH, Kaimal AJ. Association of antenatal depression symptoms and antidepressant treatment with preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:926-33 and Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: Preliminary Data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol. 64, no. 12. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. Tables 24 and 25 report preterm birth rates by age and race

f Assuming a preterm birth rate reduction of 33% among women with psychosocial risk factors

h March of Dimes. Premature birth The financial impact on business Employer expenditures and healthcare utilization figures from Truven Health Analytics, Inc. Costs of Preterm Birth. Prepared for March of Dimes, 2013. Available at: http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/premature-birth-the-financial-impact-on-business.pdf . Accessed: September 12, 2016

i Gareau S, Lòpez-De Fede A, Loudermilk BL, et al (Group prenatal care results in Medicaid savings with better outcomes: a propensity score analysis of centeringpregnancy participation in South Carolina. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:1384-93) estimate that for every preterm birth averted, approximately $25,000 US are not spent on neonatal care, not counting additional maternal payments that are associated with preterm birth that are averted. This number is one-half of the March of Dimes 2013 report of the additional cost to employers for each preterm birth (additional newborn and maternal payments).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree