Fig. 7.1

Endometrial atrophy. Endometrial atrophy. The endometrial shadow can be seen as a thin feint line

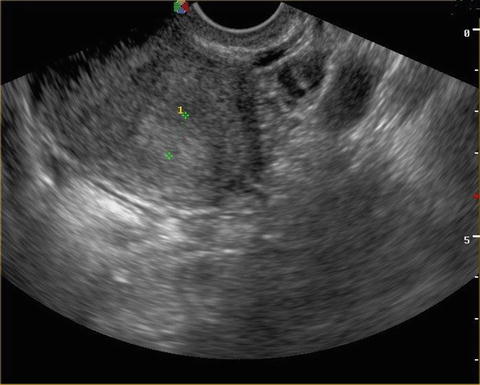

Fig. 7.2

Endometrial hyperplasia. Endometrial hyperplasia. The thickened endometrial shadow can be seen between the two calipers

If a polyp, adenomyosis or leiomyoma are found, the treatment is surgical or interventional (uterine artery embolization for unterine fibroids or magnetic resonance guided highly focused ultrasound for uterine fibroids and adenomyosis) and therefore outside of the scope of this chapter. If no abnormalities are found, endometrial biopsy should be considered. The big advantage of ultrasound, is that it can be performed on adolescents with an abdominal probe, thus precluding the necessity for vaginal or speculum examination. Doppler ultrasonography may provide additional information for characterizing endometrial and myometrial abnormalities, particularly arterio-venous malformations.

4.3 Hydrosonography

This technique is also known as saline-contrast sonohysterography, saline infusion sonography (SIS) or sonohysterography. In this technique saline is infused into the uterine cavity during transvaginal scanning. SIS separates the uterine walls and thereby clarifies the presence of focal lesions protruding into the uterine cavity [14]. As long as the cervical canal is not stenotic, SIS is relatively easy to perform. After inserting the catheter into the uterine cavity and the ultrasound probe into the vagina, a few millilitres of saline are injected. Virtually all endometrial pathology grows focally in the uterine cavity [15]. If no focal lesions are present in the uterine cavity, the odds of malignancy decrease 20-fold, and the odds of any endometrial pathology decrease 30-fold [15]. A smooth endometrium at SIS is a strong sign of normality.

As most focal lesions cannot be removed at all, or only be partially removed by blind endometrial sampling, such as pipelle, or dilatation and curettage, focal lesions should be hysteroscopically resected under direct visual control.

4.4 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is not generally recommended as a first-line procedure for investigating AUB. MRI is a good second line procedure if ultrasound reveals a bulky, polymyomatous uterus, or if adenomyosis is suspected. MRI has the advantage of distinguishing between myomas, sarcomas, and adenomyosis. Therefore, MRI can also optimize treatment strategy regarding the use of major surgery, or minimally invasive procedures. MRI can also provide a diagnostic assessment of the endometrium when the uterine cavity is inaccessible [16].

5 Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy has a few unique advantages over other forms of imaging, despite the need for a skilled endoscopic surgeon. Diagnostic hysteroscopy can be performed as an office procedure and permits direct visualization of the endometrial cavity. Therefore, it can be very valuable for diagnosing endometrial focal lesions, atrophy and hyperplasia as well as primary or secondary malformations of the uterine cavity (septum, polyp, residua, caesarean section niche, etc). Hysteroscopy also has the advantage of allowing a targeted biopsy to be taken, particularly in focal lesions which may be missed by blind endometrial sampling techniques. The likelihood of endometrial cancer diagnosis after a negative hysteroscopy result is 0.4–0.5 % [17]. In some settings, especially if uterine pathology is suspected, a diagnostic hysteroscopy can be combined with an operative procedure in the same session if required. The European guidelines [18] suggest that hysteroscopy is a second line procedure when ultrasound suggests a focal lesion, when biopsy is non diagnostic, or as an operative procedure if medical treatment fails after 3–6 months.

6 Biopsy

Histological examination is usually thought to be the gold standard for making a diagnosis of uterine pathology. Endometrial sampling for the diagnosis or exclusion of mostly hormonally induced endometrial changes (hyperplasia or endometrial cancer) is most often performed with a pipelle. The biopsy also may provide information about the hormonal status of the endometrium. However, there is a 0–54 % rate of sampling failure [19]. Another important limitation of pipelle biopsy is that it samples an average of only 4 % of the endometrium with a reported range of 0–12 % [20]. Usually a polyp is an incidental finding during endometrial sampling and most often is not entirely removed by pipelle.

Classically, endometrial sampling was performed by dilatation and curettage (D&C). Pipelle biopsy has replaced D&C, as pipelle biopsy is an office procedure, thus less invasive and less expensive than D&C. In addition, pipelle biopsy is safer, as the general anesthetic usually used in D&C is not required. D&C has been reported to lack the ability to identify uterine focal lesions [21], and blind excision of focal lesions by curettage may be incomplete.

The question arises as to when sampling is indicated. In the adolescent, there is little place for biopsy, unless absolutely necessary and might be considered only in extreme cicumstances.

Goldstein [22] summarised five large prospective studies in women with postmenopausal women. An endometrial thickness of ≤4 mm on transvaginal ultrasound with bleeding was associated with a risk of malignancy of 1 in 917 (3 cancers in 2,752 patients). Goldstein [22] concluded that in postmenopausal bleeding, biopsy is not indicated when the endometrial thickness is ≤4 mm. Furthermore, if biopsy is performed in patients with a thin endometrium, it is most likely that no tissue would be obtained for histology. In a study of 97 consecutive patients with post menopausal bleeding evaluated by endometrial biopsy, only 82 % of the patients with an endometrial thickness ≤5 mm (n = 45) had a successful Pipelle biopsy completed [23], and only 27 % of them produced a sample which was adequate for diagnosis. The results on postmenopausal women can be extrapolated to premenopausal women. However, in women with endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial sampling is indicated [24, 25], as there is a high possibility of malignancy.

Endometrial sonographic thickness as an indicator of the need for biopsy is problematic in premenopausal women with AUB, as endometrial thickness changes throughout the menstrual cycle (from 4 to 8 mm during the proliferative phase, to 8–14 mm during the secretory phase [26]). In our hands, the use of hormonal assessment prior to endometrial sampling has proven very to be clinically important: Determination of blood estradiol, progesterone and beta-hCG levels prior to endometrial sampling can avoid sampling of a pregnant or postovulatory endometrium and allow re-assessment of the ultrasound findings and endometrial thickness in view of the hormonal state of the patient.

7 Principles of Treatment

Treatment has a number of objectives, to lessen or stop the bleeding, and to provide long term relief. AUB due to a structural problem (polyp, adenomyosis, and leiomyoma, etc.) are treated surgically, and therefore outside the scope of this chapter. Medical management of endometrial cancer has been described in Chap. 12. The primary goal of medical therapy should be to stabilize the endometrium with estrogen to provide initial hemostasis, followed by combined estrogen/progestogens for endometrial stability and induction of a menstruation-like withdrawal bleed. This induced bleeding can at first be strong because of a medical “curettage” of a thickened endometrial layer and is usually limited in time, especially if hormonal therapy is continued afterwards. However, this basic plan of action should be modified according to the patients needs, desire for fertility, anemia, endometrial thickness etc. In addition to hormonal therapy, other medical treatment modalities are available such as NSAIDS, tranexamic acid, and receptor modulators etc. Some specific modifications are listed below.

7.1 Adolescent AUB

The presence of irregular and heavy AUB is a relatively common cause of concern among adolescents and their parents, as well as a frequent cause of visits to emergency departments, gynaecologists, and pediatricians [1]. Adolescent patients pose particular diagnostic problems because the characteristics of normal puberty often overlap with signs and symptoms of PCOS. The aims of AUB treatment in adolescents is therefore to stop bleeding, prevent or reverse anemia and achieve adequate cycle control. Anemia can be corrected with iron supplementation, with added folate and vitamin B12 if necessary, but these alone will not address the underlying cause of anemia: bleeding. Bleeding can usually be controlled with combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) taken continuously for several months. Alternatively, monophasic OCPs containing 20–30 μg of ethinyl estradiol and a relatively androgenic progestogen such as 0.3 mg of norgestrel or 0.15 mg of levonorgestrel can be used cyclically. If breakthrough bleeding occurs, or heavy menstrual bleeding persists and other causes of AUB have been excluded, the dose can be doubled for a short period of time to two pills per day. Since combined hormonal contraceptives can increase levels of coagulation factors such as factor VIII and von Willebrand factor, OCP’s might have an additional effect in cases of an underlying coagulopathies.

If estrogen is contraindicated due to a history of thrombosis, migraine, hypertension etc., progestogens alone can be used. Examples are: oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), or norethisterone (norethindrone acetate, NETA). Oral MPA 10 mg daily or NETA 5 mg daily given for 10–14 days each month generates a secretory endometrium that induces a withdrawal bleed 1–7 days after stopping the medication. However, (NETA) can be aromatised to ethinylestradiol [27]. Kuhnz et al. [28] reported that this conversion resulted in a dose that was equivalent to taking 4–6 μg of ethinyl estradiol for each 1 mg of NETA ingested. The conversion ratio of NETA to EE has been subsequently estimated to be between 0.2 and 0.33 % for different doses [29], Chu et al. [30] concluded that a daily dose of 10–20 mg NETA equates to taking a 20–30 μg ethinyl estradiol COC, Conversion to estrogen and the estrogenic effects are of no relevance when these progestogens are taken in low-dose progestogen-only, or combined oral contraceptive pills [31] but probably explains why high-dose norethisterone and its ester are effective at delaying and regulating menstrual bleeding. There are no similar implications for other progestogens in either low or high doses, since these structural issues do not apply [32–34].

It has been reported in other chapters in this book that dydrogesterone binds the progesterone receptor up to 50 % more than progesterone itself. However, dydrogesterone stimulates the progesterone receptor alone. It may therefore be appropriate in patients with a thickened endometrium in whom progesterone only effects are required. However, if there is a thin endometrium, estrogen will also be required to provide hemostasis, in addition to dydrogesterone.

The LNG-IUS or etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring are other possibilities, but are not usually acceptable in adolescents. Clomiphene citrate has occasionally been used in anovulatory adolescents. Clomiphene is a SERM which blocks the estrogen receptor in the hypothalamus, thus inhibiting the negative feedback. Hence there is up-regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Subsequently, estrogen levels can rise to the level required to induce LH release. The use of clomiphene has recently been reported again as a possible therapy in anovulatory adolescents [35]. During the use of clomiphene citrate in adolescents the chance of conception and the rare possibilities of side-effects (headaches, vision changes, ovarian hyperstimulation, etc.) should be taken into consideration. Further, studies demonstrated that prolonged use of clomiphene might be associated with ovarian cancer.

7.1.1 Acute Uterine Bleeding

In the case of acute AUB, there is a need to stop the bleeding immediately. Hormonal management is the first line of medical therapy if there are no known or suspected bleeding disorders. Treatment options include oral estrogenic compounds, IV conjugated equine estrogen, combined oralcontraceptives (OCs), and oral progestins. If AUB can result from estrogen breakthrough bleeding then a logical approach is to stop the process by adding estrogens orally or parenterally. This approach usually leads to a very quick cessation of bleeding and after several days without bleeding, combined estrogen and progestagen treatment can be administered until the planned time of the next menstruation.

Intravenous conjugated equine estrogen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acute AUB. A dose of 25 mg can be given intravenously. However, the patient requires cycling by progestogen immediately afterwards. In one randomized controlled trial of 34 women, IV conjugated equine estrogen stopped bleeding in 72 % of participants within 8 h of administration compared with 38 % of participants treated with a placebo [36]. Little data exist regarding the use of IV estrogen in patients with cardiovascular or thromboembolic risk factors.

High doses of oral contraceptive pills as well as MPA have been used with variable success [37]. For COC large doses such as three pills per day may be required with the resulting side-effects of large doses of hormones. However, estrogen only is probably more effective than COC. Progestogens can be used as sole agents in acute AUB. MPA can be given up to 20 mg three times daily for a week or NETA can be given in doses up to 40 mg daily in divided doses until bleeding stops and then the dose can be tapered down [38]. Another treatment regimen for acute AUB is depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate 150 mg given intramuscularly followed by MPA 20 mg given orally thrice daily for 3 days. This treatment stopped bleeding within 5 days in all 48 women in a pilot study. Study participants reported infrequent side effects and high satisfaction.

Monro et al. [37] compared the results of oral contraceptives three times daily for 1 week with MPA administered three times daily for 1 week. The study found that bleeding stopped in 88 % of women who took OCs and 76 % of women who took MPA within a median time of 3 days.

The author uses a regimen of oral synthetic estradiol (Estrofem) 2–4 mg followed by oral MPA 10 mg or micronized progesterone 200 mg nocte. This regimen results in good relief of acute AUB.

7.2 Perimenopausal Bleeding

Perimenopausal patients need to have organic disease excluded before medical therapy is prescribed. As mentioned above, there is a higher incidence of organic disease in this age group. As in the other age groups, anemia may need to be corrected. Perimenopausal women with AUB, may be treated with cyclic progestin therapy, low-dose oral contraceptive pills, the levonorgestrel IUD, or cyclic hormone therapy. Each treatment modality has advantages and disadvantages. The OCP and LNG-IUS provide contraception, in addition to hemostasis. Estrogen therapy, also provides relief from perimenopausal symptoms, such as hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal atrophy. The choice of therapy often is guided by the patient’s priorities. Endometrial thickness will also give an idea of whether estrogen is required, or whether the patient can be managed on progestogen alone. In a study of 120 perimenopausal women treated by continuous estrogen and cyclic progestin or cyclic progestogen alone [39], 86 % of women in the combined treatment group experienced cyclic menstrual bleeding, and reduced vasomotor symptoms. In addition, 76 % of the women rated their bleeding as normal in amount and duration.

7.2.1 LNG-IUS

The LNG-IUS is particularly useful for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding in women who desire contraception. The LNG-IUS has been shown to be the most effective treatment in reducing menstrual blood loss compared with other medical therapies for chronic AUB and can reduce menstrual blood loss by more than 80 % and even induce hormonal amenorrhea [40]. However, the LNG-IUS takes time to achieve adequate endometrial quiescence. Initially there may be increased bleeding. The LNG-IUS results in greater increases in hemoglobin and serum ferritin levels after 6 months compared with oral MPA from day 16 to 26 of the menstrual cycle [41]. Women also reported higher rates of subjective improvement in their bleeding despite the known initial side effect of irregular bleeding after LNG-IUS insertion. The efficacy of the levonorgestrel IUS was evaluated by Vilos et al. [42] in 56 obese perimenopausal women with AUB. The mean age was 42 years and the mean body mass index was greater than 30. At the 48-month follow-up, the satisfaction rate was 75 %; amenorrhea and hypomenorrhea were noted with longer use. Hence, The LNG-IUS is an excellent long-term treatment modality for heavy menstrual bleeding when contraception is also required.

7.2.2 Endometrial Hyperplasia

Endometrial hyperplasia, whether simple or complex, with or without atypia has malignant potential. Figure 7.2 shows a sonogram of endometrial hyperplasia. If atypia is present, there is a 29 % risk of progression to endometrial cancer [43]. However, in simple hyperplasia, the risk can be as low as 1 %. Therefore treatment should aim at eradicating the condition. In the perimenopausal or post menopausal woman, hysterectomy is probably the best treatment option. However, in younger women, endometrial hyperplasia can be found in anovulatory cycles, polycystic ovary syndrome, or obesity. If fertility is desired, progestogens are the mainstay of treatment. In hyperplasia, there is little need for estrogen as the condition is due to excess stimulation with unopposed estrogen. Therefore, progestogens can be used to convert the endometrium to a secretory pattern. Once endometrial hyperplasia has been diagnosed, it is essential to repeat the biopsy 3–6 months afterwards to confirm that regression has taken place. However, it has been reported that the median length of progestin treatment required for regression can be 9 months. Additionally endometrial hyperplasia is closely related to insulin resistance and metabolic disorder. A low body mass index of <35 kg/m2 has been reported to be associated with a high resolution rate in patients receiving progestogens [44]. There are case reports which show that if there is no response to progestogens, reversal of hyperplasia could be induced with metformin in addition to progestogens [45, 46].

The main progestogens for treating endometrial hyperplasia are megestrol acetate, medroxyprogesterone 17-acetate [MPA], dydrogesterone and the LNG- IUS. However, there is no consensus on dose, treatment, duration, route of administration, or the most effective progestogen [47]. No evidence is available from randomized controlled trials. Hence treatment is somewhat empiric, and administered in a trial and error fashion. The overall response rate has been reported to be approximately 70 %. Moreover, oral progestins are associated with poor compliance and systemic side effects that may limit overall efficacy [48]. Below are some of the advantages and disadvantages of each regimen.

Megestrol has antiestrogenic and anti androgenic effects, which may not be acceptable to the patient, or may decrease compliance. Megestrol acetate also has glucocorticoid effects. Symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome, steroid diabetes, and adrenal insufficiency, have been reported with the use of megestrol acetate (in the medical literature, albeit sporadically) [49].

Medroxy progesterone acetate (MPA) however, is an agonist of the progesterone, androgen, and glucocorticoid receptors [50]. Hence there may be side effects of acne and hirsutism in some patients. MPA has glucocorticoid properties, and as a result can cause Cushing’s syndrome, steroid diabetes, and adrenal insufficiency. Mesci-Haftac et al. [51] assessed 69 patients with simple hyperplasia, who received MPA. Hyperplasia persisted in 19.7 %. The regression rate to benign findings was 77.1 %. Atypia and progression to complex hyperplsia occurred in 3.2 % of the patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree