Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Steven R. Goldstein

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Abnormal uterine bleeding is a significant issue and accounts for 20% of all gynecologic visits. Like most of medicine, the clinical approach begins with a thorough detailed history. Many physicians have simply encompassed the all inclusive term menometrorrhagia. Much more information can be gleamed from the timing and character of the bleeding as well as the clinical backdrop in which it occurs. The American College of Obstetricians a Gynecologists (ACOG) Practice Bulletin No. 14 states, “There is a distinct increase in the incidence of endometrial carcinoma from ages 30–34 years (2.3/1000,000 in 1995) to ages 35–39 (6.1/1000,000 in 1995). Therefore, based on age alone, endometrial assessment to exclude cancer is indicated in any woman older than 35 years who is suspected of having anovulatory uterine bleeding.”

Although endometrial carcinoma is rare in women younger than 35 years, patients between age 19 and 35 who do not respond to medical therapy or have prolonged periods of unopposed estrogen stimulation secondary to chronic anovulation are candidates for endometrial assessment.

The hallmark of ovulation is the regularity and predictability of the cycle, usually within 3 days in terms of the interval between them. To most women, any bleeding from the vagina is thought of as their “period.” To the astute clinician, however, a menses is a bleed that is preceded by ovulation. If a pregnancy does not ensue 14 days after ovulation, a menses will occur. If a woman does not ovulate, estrogen is produced but without corresponding progesterone. The timing of bleeding probably is the result of fluctuating levels of estrogen, which can destabilize the functionalis of the endometrium and cause some degree of shedding. Such anovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding, often explained to patients as “hormone imbalance,” is characterized by its lack of predictability in terms of cyclicity, amount, and/or duration of flow as well as accompanying symptoms, if any. Thus, it usually results in metrorrhagia, which is defined as intermenstrual, irregular, or otherwise noncyclic bleeding. The problem for clinicians is that organic pathology including polyps, submucous myomas, hyperplasia, or even frank carcinoma can result in irregular vaginal bleeding that can be indistinguishable from dysfunctional anovulatory bleeding. Menorrhagia, by itself, without a component of metrorrhagia, may be physiologic. With increasing parity, the amount of surface area of the endometrial cavity will increase, resulting in heavier flow. However, organic pathology such as an enlarged uterine cavity associated with myomas even if there is no submucous component, functional endometrial polyps in synchrony with the surrounding endometrium, adenomyosis, or coagulation defects can also be present. Finally, many women may present with a combination of menorrhagia and metrorrhagia and may have more than one process to account for it. For instance, a woman with an asynchronous endometrial polyp who is still ovulatory or a patient with submucous myomas may display a mixed picture. Furthermore, many patients may not keep good menstrual calendars or may have so much irregularity as to render their ability to help meaningless.

Obviously, other pertinent historic information concerning contraceptive method, possibility of pregnancy, and concomitant medications as well as potential medical confounders should be included. In addition, although this chapter deals with abnormal uterine bleeding, a thorough pelvic examination is essential to exclude any vaginal

or cervical pathology as the source of the bleeding. Pregnancy also must always be excluded.

or cervical pathology as the source of the bleeding. Pregnancy also must always be excluded.

Postmenopausal bleeding is a unique but crucial subset. Since menopause is defined as the final menstrual period, it obviously is a retrospective diagnosis. In late perimenopausal patients, ovarian function may be wildly sporadic, so long episodes of amenorrhea, hot flashes, and even laboratory determinations interpreted as menopausal (increased follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH], decreased estradiol) may be followed by some bleeding, staining, or spotting that may represent agonal episodes of ovarian function. Thus, an absolute definition of postmenopausal bleeding may be difficult; but generally, any bleeding, spotting, or staining after 12 months of amenorrhea should be viewed as “endometrial cancer until proven otherwise” and endometrial evaluation becomes mandatory.

Endometrial Evaluation

There are a number of procedures to evaluate the endometrium in premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding as well as postmenopausal women with bleeding in whom endometrial evaluation is indicated. Although numerous studies exist, there are no good prospective, patient-outcome, randomized head-to-head trials. Thus, patient preference; clinician training; and skill, cost, and access issues will determine what method of evaluation best suits a patient. Initially, curettage in the hospital with anesthesia was the gold standard. First described in 1843, it was once the most common operation performed on women in the world. Even 50 years ago, it was understood that the technique missed endometrial lesions in many cases, especially those that were focal (polyps). Furthermore, less then half of the endometrial cavity went unsampled.

In the 1970s, vacuum suction curettage devices first allowed for endometrial sampling without anesthesia in an office setting. Such procedures, although office based, were cumbersome and resulted in great patient discomfort.

Subsequently, cheaper, smaller, less painful plastic catheters with their own internal pistons to generate suction became popular. These were found to have similar efficacy but better patient acceptance when compared with the vacuum suction devices. One study showed that the percentage of endometrial surface area sampled by one such suction piston biopsy device (Pipelle) was 4%.

In one widely publicized study by Stovall and colleagues, the Pipelle had a 97.5% sensitivity to detect endometrial cancer in 40 patients who were undergoing hysterectomy. The shortcoming of that study was that the diagnosis of malignancy was known before the performance of the specimen collection.

In another study, however, Guido and associates also studied the Pipelle biopsy in patients with known carcinoma who were undergoing hysterectomy. Among 65 patients, a Pipelle biopsy provided tissue adequate for analysis in 63 (97%). Malignancy was detected in only 54 patients (83%). Of the 11 with false-negative results, five (8%) had disease confined to endometrial polyps, and three (5%) had tumor localized to <5% of the surface area of the cavity. The surface area of the endometrial involvement in that study was ≤5% of the cavity in three of 65 (5%); 5% to 25% of the cavity in 12 of 65 (18%), of which the Pipelle missed four; 26% to 50% of the cavity in 20 of 65 (31%), of which the Pipelle missed four; and >50% of the cavity in 30 of 65 patients (46%), of which the Pipelle missed none. These results provide great insight about the way endometrial carcinoma can be focally distributed over the endometrial surface or confined to a polyp. Because tumors localized in a polyp or a small area of endometrium may go undetected, the authors in that study concluded that the “Pipelle is excellent for detecting global processes in the endometrium.”

Other studies of the Pipelle in patients with known carcinoma have shown sensitivities of 82% to 93%. From these data, it seems that undirected sampling, whether through curettage or various types of suction aspiration, often will be fraught with error, especially in cases in which the abnormality is not global but focal (polyps, focal hyperplasia, or carcinoma involving small areas of the uterine cavity).

Transvaginal Ultrasound

Introduced in the mid 1980s, the vaginal probe utilizes higher frequency transducers in close proximity to the structure being studied. It yields a degree of image magnification that is a form of “sonomicroscopy.” In the early 1990s, it was utilized in women with postmenopausal bleeding to see if it could predict which patients lacked significant tissue and could avoid dilation and curettage (D&C) or endometrial biopsy and its discomfort, expense, and risk. Consistently, the finding of a thin distinct endometrial echo ≤4 to 5 mm has been shown to effectively exclude significant tissue in women with bleeding.

Among 163 women with postmenopausal bleeding and an endometrial echo ≤4 mm, there was one cancer (0.6%). Among 97 women with postmenopausal bleeding and endometrial echo <5 mm, there were no cancers. In another Scandinavian study of 394 women with postmenopausal bleeding, there were no cases of cancer as compared with curettage, as well as through follow-up for 10 years, if the endometrial echo was <4 mm.

Since that time, a number of large multicentered trials have taken place. In the Nordic trial, of 1,168 postmenopausal women with bleeding and transvaginal ultrasound echo ≤4 mm, there were no cancers on curettage. An Italian multicentered study of 930 women with postmenopausal bleeding had an incidence of endometrial cancer of 11.5%. When the endometrial echo was ≤4 mm,

there were two cases of endometrial cancer (negative predictive value 99.79%). When the endometrial echo was ≤5 mm, there were four cases of endometrial cancer (negative predictive value 99.57%). When the endometrial echo was ≤5 mm, there were no cases of complex hyperplasia.

there were two cases of endometrial cancer (negative predictive value 99.79%). When the endometrial echo was ≤5 mm, there were four cases of endometrial cancer (negative predictive value 99.57%). When the endometrial echo was ≤5 mm, there were no cases of complex hyperplasia.

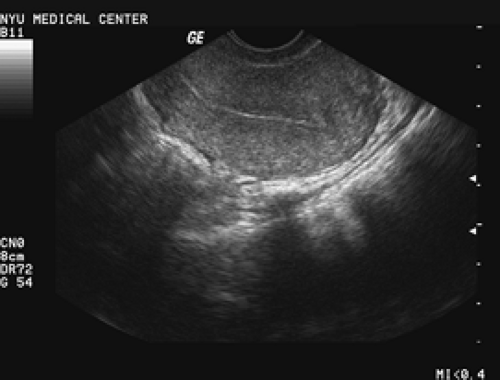

Endometrial thickness should be measured on a sagittal (long axis) image of the uterus, and the measurement should be performed on the thickest portion of the endometrium, excluding the hypoechoic inner myometrium. It is a “double-thickness” measurement from basalis to basalis. If fluid is present, it usually is associated with cervical stenosis and atrophy. In such cases, the layers are measured separately and should be symmetric. The endometrial cavity is a three-dimensional structure, and attempts must be made to image the entire cavity. A well-defined endometrial echo should be seen taking off from the endocervical canal (Fig. 37.1) and should be distinct. Often, fibroids, previous surgery, marked obesity, or an axial uterus may make visualization suboptimal. In these cases, ultrasound cannot be relied on to exclude disease. The next step for such patients with bleeding should be either hysteroscopy or saline infusion sonohysterography, depending on the skill set and preference of the physician and patient.

Sonohysterography

The use of fluid instillation into the uterus coupled with high-resolution transvaginal probes allows tremendous diagnostic enhancement with an inexpensive, simple, well-tolerated office procedure.

The addition of saline infusion sonohysterography can reliably distinguish perimenopausal patients with dysfunctional abnormal bleeding (no anatomic abnormality) from those with globally thickened endometria or focal abnormalities.

A clinical algorithm was proposed and studied in a large prospective trial of perimenopausal women with abnormal bleeding by using unenhanced transvaginal ultrasonography, followed by saline infusion sonohysterography for selected patients, and then either no endometrial sampling, undirected endometrial sampling, or visually directed endometrial sampling, depending on whether the ultrasonographically based triage revealed no anatomic abnormality, globally thickened endometrium, or focal abnormalities, respectively (Fig. 37.2). In that study, 280 patients (65%) displayed a thin, distinct, symmetric endometrial echo ≤5 mm on days 4 to 6, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding was diagnosed. Saline infusion sonohysterography was used in 153 patients (35%). Of these procedures, 44 (29%) were performed because of the inability to adequately characterize and measure the endometrium (Fig. 37.3), and 109 (71%) were done for endometrial measurement ≥5 mm. Sixty-one of those patients then had both anterior and posterior endometrial thickness that was symmetric and <3 mm, compatible with dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Fifty-eight patients (13%) had focal polypoid masses (Fig. 37.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree