16.2 Abnormal bleeding and clotting

Abnormal bleeding is the result of a disorder of one of the following:

Clinical approach to diagnosis

Bleeding disorder assessment

• History to determine normal from abnormal is the most valuable tool.

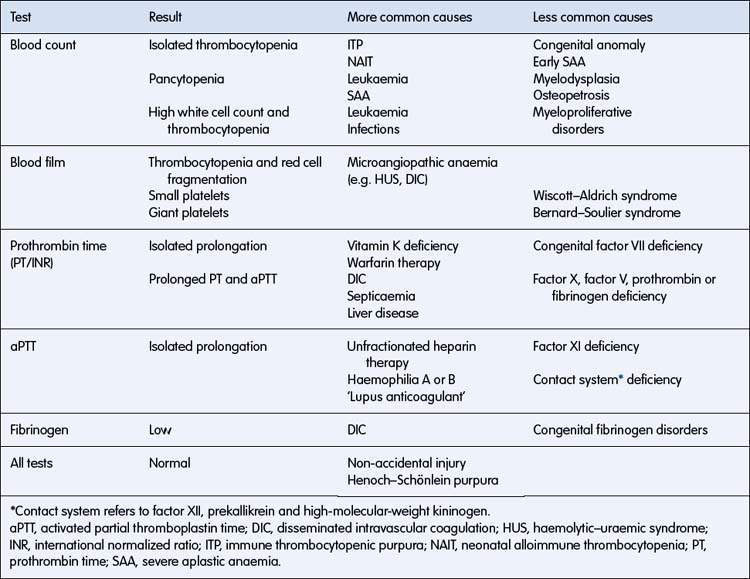

• Simple coagulation tests such as platelet count, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), prothrombin time (PT/international normalized ratio (INR)) and fibrinogen will confirm the majority of diagnoses.

• Mucosal bleeding needs assessment for von Willebrand disorder.

History

What is abnormal?

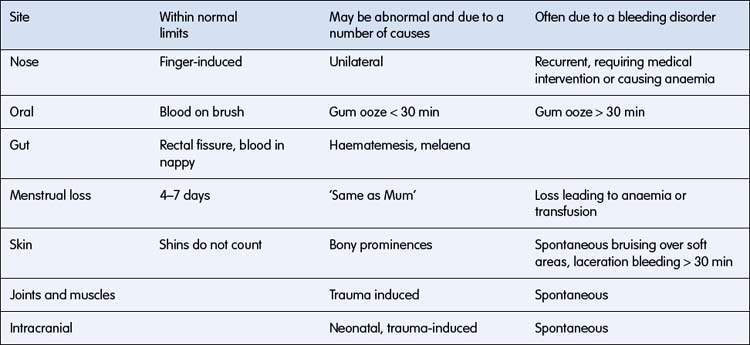

The main question to answer in the history is whether the bleeding symptoms are within or outside normal limits. Isolated bruises over the shins are common, whereas spontaneous petechiae are abnormal. Finger-induced epistaxis is common and not indicative of a bleeding disorder; however, recurrent nose bleeds lasting for more than 10 minutes or leading to anaemia are often related to a bleeding disorder. Table 16.2.1 gives some clinical guidance.

When did the bleeding start?

Prenatal and neonatal

• Congenital infection may result in a bleeding disorder.

• Mucosal bleeding occurs with haemorrhagic disease of the newborn.

• Umbilical stump bleeding is associated with factor XIII deficiency and dysfibrinogenaemias.

• Intracranial haemorrhage may occur with factor deficiencies and with neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia.

• Prolonged bleeding following circumcision is suggestive of haemophilia and may be the presenting feature of haemorrhagic disease of the newborn.

Sudden onset

• Usually indicates an acute problem such as immune thrombocytopenic purpura.

• Non-accidental injury may have a haemorrhagic presentation with inadequate explanations for each specific bruise, which may have an unusual distribution (see Chapter 3.9). Skeletal trauma and other stigmata of non-accidental injury may be present.

Where is the bleeding?

Specific bleeding sites have characteristic associations:

• Joint bleeding: haemophilia A and B

• Nasal mucosa: local irritation; von Willebrand disorder and platelet dysfunction

• Gums, periosteum, skin: scurvy

• Gastrointestinal: haemorrhagic disease of the newborn in babies; liver disease in older children

• Retro-orbital: haematological malignancy or disseminated solid tumour.

What is the context of bleeding?

Drug ingestion

Drugs may produce abnormal bleeding through:

• depression of clotting factors: anticoagulants, liver toxins

• bone marrow depression: chloramphenicol, cytotoxic agents, radiation

• antigen–antibody reactions with platelet membranes: quinine group of drugs

• direct inhibition of enzymes in platelets: aspirin effects on platelet cyclo-oxygenase.

Physical examination

The following should be noted on physical examination.

Bleeding due to platelet disorders

Bleeding disorders resulting from platelet abnormalities are usually due to thrombocytopenia but may be due to qualitative platelet defects. The various types of inherited and acquired thrombocytopenia are listed in Table 16.2.3.

Table 16.2.3 Inherited and acquired thrombocytopenias

| Disorder | Key Information | |

|---|---|---|

| Acquired | ||

| Neonatal | Immune thrombocytopenia | Neonatal alloimmune or maternal autoimmune |

| Intrauterine infection | TORCH | |

| Pre-eclampsia | ||

| Birth asphyxia | ||

| Giant haemangioma | ‘Kasabach–Merritt syndrome’ features platelet consumption | |

| Any age | Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) | The most common acquired thrombocytopenia |

| Inherited | ||

| With platelet dysfunction | Examples include Bernard–Soulier syndrome and Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome | Rare |

| Without platelet dysfunction | Examples include Fanconi anaemia and Alport syndrome | Rare |

| Mediterranean macrothrombocytopenia | Large platelets, autosomal dominant |

TORCH, toxoplasmosis, other (e.g. HIV and parvovirus B19), rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex.

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura

Features of typical acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree