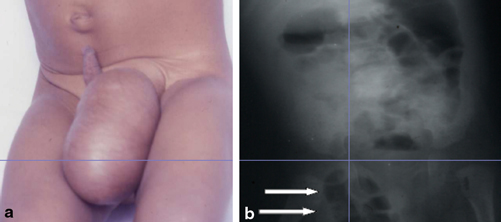

Fig. 4.1

Clinical photographs (a and b) of a large inguinoscrotal hernia

They are commonly seen in approximately 3–5 % of full-term infants.

Inguinal hernias are three times more common in premature infants (hernias are found in as many as 30 % of prematurely born babies).

These hernias appear more frequently in boys than in girls (the male to female ratio is 10:1).

Girls however present more with bilateral inguinal hernias than boys.

Inguinal hernias are more common on the right side (60 % of the time) and in some cases it is located on the left side or can be bilateral.

Inguinal hernias are further divided into:

The more common indirect inguinal hernia in which the hernia enters through the internal inguinal ring (caused by failure of embryonic closure of the processus vaginalis).

The direct inguinal hernia type , where the hernia contents pass through a weak spot in the back wall of the inguinal canal which is formed by the transversalis fascia.

Indirect inguinal hernias appear lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels while direct inguinal hernias occur medial to the inferior epigastric vessels.

About 50 % of inguinal hernias are present clinically in the first year of life, especially in the first 6 months.

There is a familial tendency for inguinal hernia.

The incidence of inguinal hernias is higher in those infants with:

1.

Increased intra-abdominal pressure (Fig. 4.2)

Fig. 4.2

Intraoperative photograph showing right-sided inguinal containing a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt

2.

Undescended testis

3.

Congenital heart disease

4.

Cystic fibrosis

5.

Connective tissue disorders

6.

Bladder exstrophy

7.

Testicular feminization syndrome

8.

Intersex disorders

Inguinal hernia also occurs more commonly in patients with chromosomal disorders, microdeletion disorders, and single gene disorders.

A chromosomal study should be done if testicular feminization syndrome is suspected. The possibility of testicular feminization syndrome must be kept in mind in females who present with bilateral inguinal hernia.

Inguinal hernias are classified into:

Reducible hernia: one in which the hernia contents can be pushed back into the abdomen by putting manual pressure to it.

Irreducible hernia: one in which the hernia contents cannot be pushed back into the abdomen by applying manual pressure.

Irreducible inguinal hernias are considered an emergency and if it fails to be reduced after sedation then an emergency herniotomy should be done (Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.3

A clinical photograph showing an irreducible right inguinal hernia

Obstructed inguinal hernia : a hernia in which the lumen of the herniated part of intestine is obstructed but the blood supply is intact.

Incarcerated inguinal hernia : a hernia in which adhesions develop between the wall of hernial sac and the intestines preventing it from being reduced.

Incarceration occurs in about 12 % of infants and young children with an inguinal hernia, often during the first 6 months of life.

The rate of incarceration decreases to 1 % at 8 years of age.

Immediate surgery is indicated for the incarcerated hernia that is manually irreducible (Fig. 4.4).

Fig. 4.4

a Clinical photograph showing right incarcerated inguinal hernia containing bowel loops. b Abdominal x-ray showing bowel loops in an incarcerated right inguinal hernia

Strangulated inguinal hernia : A hernia that is irreducible and in which the blood supply of the herniated intestines is compromised leading to ischemia. Infarction of the small bowel, testis, or ovary may result (Figs. 4.5 and 4.6).

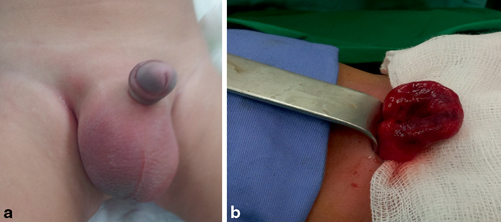

Fig. 4.5

a Clinical photograph showing right strangulated inguinal hernia. b Intraoperative photograph showing an ischemic bowel loop in an irreducible strangulated inguinal hernia

Fig. 4.6

Intraoperative photograph showing a necrotic ovary in an irreducible strangulated left inguinal hernia

Infants 6 months of age and younger who have inguinal hernias have a much higher risk of strangulation than older children.

The content of an inguinal hernial sac is commonly small intestines but may also contain ovary, testes, Meckel’s diverticulum, appendix, and urinary bladder.

Amyand’s hernia: an inguinal hernia in which the content of the hernial sac is the vermiform appendix.

Littre’s hernia: an inguinal hernia in which the content of the hernial sac contains a Meckel’s diverticulum. It is named after the French anatomist Alexis Littré (1658–1726).

Busse’s hernia: an inguinal hernia in which the testicle is within the hernia sac.

Richter’s hernia: a hernia in which only one side of the wall of the bowel is trapped into the hernial sac, which can result in bowel strangulation leading to perforation through ischemia without causing bowel obstruction. It is named after the German surgeon August Gottlieb Richter (1742–1812).

Sliding hernia : occurs when the herniated organ forms part of the hernia sac. The colon and the urinary bladder are the commonest to be involved in a sliding hernia.

Pantaloon hernia (saddle bag hernia): This is a combined direct and indirect inguinal hernia, when the hernial sac protrudes on either side of the inferior epigastric vessels.

Maydl’s hernia : This is seen when two adjacent loops of small intestines are within a hernial sac with a tight neck. The intervening portion of bowel within the abdomen is deprived of its blood supply and eventually becomes necrotic.

Surgical repair of inguinal hernia shortly after diagnosis is recommended for all patients, including premature infants. This is to avoid complications such as strangulation.

There is controversy about whether the contralateral groin should be explored. Today, most surgeons do not routinely perform a contralateral exploration unless a contralateral inguinal hernia or patent processus vaginalis can be demonstrated either by preoperative ultrasonography or by intraoperative laparoscopy.

A hernia develops in the other side of the groin in about 30 % of children who have had hernia surgery. This is more so if the initial hernia was on the left side.

Complications of inguinal hernia repair include:

Wound infection

Hematoma

Scrotal edema

Ascent of testis

Testicular atrophy

Recurrence

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair has become an alternative to the conventional open herniotomy. This procedure is safe, reproducible, and technically easy for experienced laparoscopic surgeons. It also does not impair testicular perfusion. The main advantages of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair over conventional herniotomy are:

Less postoperative pain

Earlier postoperative recovery

Better wound cosmesis

The ability to detect and simultaneously repair contralateral patent processus vaginalis.

Umbilical Hernia:

An umbilical hernia results from imperfect closure or weakness of the umbilical ring (Fig. 4.7).

Fig. 4.7

A clinical photograph showing an umbilical hernia

These hernias are common in infants and young children and make up roughly 5–10 % of all primary hernias.

Umbilical hernias are about 10 times more common in blacks than in whites.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree