- Specific nutritional requirements

- Breastfeeding

- Artificial feeding/formulas

- Techniques of artificial feeding

- Feeding the preterm infant

- Total parenteral nutrition

- Common feeding disorders

Introduction

Besides meeting nutritional requirements and promoting growth, early nutrition has biological effects on the individual with important implications for their later life as an adolescent and adult. Over the last decade or so, it has also been shown that human infants, like other species, are ‘programmed’ by early nutrition for long-term outcomes such as effect on blood pressure (hypertension) insulin resistance (diabetes), tendency to obesity, allergies and neurodevelopmental outcomes including cognitive function. Thus it makes sense that these findings are factored into the design of modern nutritional strategies.

The ideal food for healthy full-term infants is breast milk. If the baby is born growth restricted, the volume of milk required is higher than for a normally grown baby of the same age (see below). Premature infants have different nutritional requirements from full-term infants and need to be fed either directly into the bowel (enteral feeding) or intravenously (parenteral nutrition).

Specific Nutritional Requirements

Fluids

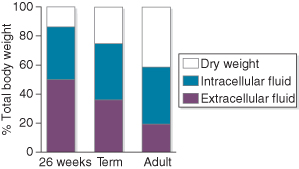

Water is the major constituent of infants, but its proportion varies with maturity (Fig. 9.1). Newborn infants, especially preterm ones, have a higher percentage of total body water than children and adults, but the proportion decreases with age as ability to conserve water increases. For this reason, the daily requirement of the newborn is relatively higher than that of older children, and that of the premature infant is higher still. Mechanisms for conserving water are often poorly developed in immature infants, and their requirements depend on conceptual age, postnatal age and environment.

Figure 9.1 Total body water and extracellular fluid expressed as percentages of body weight.

Redrawn from Dear (1984), with permission from Reed Business Publishing.

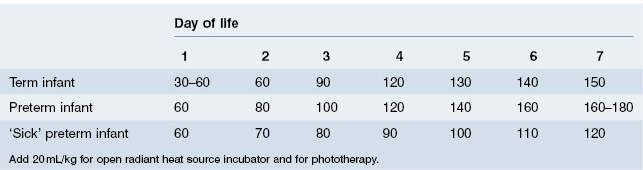

A healthy breastfed infant will consume as much fluid as is required, given ready access to the breast. Healthy bottle-fed infants will also ‘know’ how much fluid they need and should be allowed to consume milk when they want it, to the volume that satisfies them. Unfortunately, many mothers feel that their baby should take all the milk at every feed, and overfeeding may become a problem. In addition, ill or premature babies need to be given their requirements as they cannot be relied upon to take what they need. For these reasons, recommended feeding schedules have been devised (Table 9.1). These fluid requirements will be maintained up to 3 months of age, and then slowly reduced to 100 mL/kg/day by the age of 1 year.

Table 9.1 Recommended feeding schedules (fluid volume mL/kg according to day of life)

Infants who have suffered intrauterine growth restriction should be fed to an expected weight as if they had grown normally in utero. Ill preterm infants, particularly those with lung disease, may tolerate fluids poorly and develop worsening lung disease, patency of ductus arteriosus and oedema. Some very immature infants may lose large amounts of water through their kidneys or skin. In such cases a significantly higher fluid intake may be required.

For these reasons, recommended feeding schedules are of little value in sick infants: the fluid intake must be tailored to the infant’s requirements and state of hydration. Clinical assessment of hydration is made by skin turgor, fontanelle tension, moistness of the mucous membranes and urine output. In practice, clinical methods for assessing fluid requirements are unreliable: laboratory investigations are more helpful. Serum sodium, potassium, creatinine, osmolality and haemoglobin (haematocrit) should be measured. In addition, urinary osmolality or specific gravity (SG) is an important measurement. Daily weighing is a most valuable assessment of hydration and growth.

Serum osmolality may be affected by hyponatraemia, hyperglycaemia or uraemia, and may be unreliable under these circumstances. Similarly, glycosuria or proteinuria may affect urinary SG. In practice we aim to keep the urinary SG between 1005 and 1010, increasing the fluid volume if the urine becomes more concentrated, and consider fluid reduction in the presence of very dilute urine.

Inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (IADH) secretion is a relatively common condition in both premature and full-term infants with severe lung or cerebral disorders. It may also be seen following neonatal surgery. The hallmark is dilute serum (low serum sodium and osmolality) with concentrated urine. Peripheral oedema is often present. The treatment is fluid restriction until the serum osmolality returns to the normal range (270–285 mmol/L). If serum sodium is dangerously low (<118 mmol/L), careful correction with hypertonic saline infusion may be needed to avoid complications such as cerebral oedema (water intoxication)

Energy and Macronutrients

Energy requirements for optimal growth depend on the baby’s birthweight, gestational age and state of health. Ill babies are likely to be more catabolic and will have greater energy requirements. In addition, the smaller the infant the greater are the requirements per kilogram, and this is particularly so in infants who have suffered intrauterine growth restriction. Table 9.2 gives the energy requirements of various groups of infants for optimal growth. Of the recommended 120 kcal/kg per day of energy for the preterm infant, only 25 kcal/kg per day are for energy storage for growth.

Table 9.2 Energy requirements for optimal growth at the end of the first week of life

| Daily energy requirement | ||

| (kcal/kg) | (kJ/kg) | |

| Premature infant | 120 | 516 |

| Small for gestational age | 140+ | 602 |

| Term infant | 100 | 403 |

Carbohydrate

The carbohydrate of human milk is predominantly lactose (90–95%) with small amounts of oligosaccharides (5–10%). Lactose (a disaccharide made up of glucose and galactose) must be metabolized to glucose for energy utilization in the brain and other organs. Approximately 40% of the infant’s total energy requirement comes from the carbohydrate in milk.

Fat

Fat in milk provides approximately half of the infant’s energy requirements. Human milk fat is better absorbed than cows’ milk fat. The mature infant absorbs about 90% of the fat in human milk, but infants weighing less than 1500 g absorb only 75–80% of fat from human milk, and less from artificial milk. Unsaturated fatty acids are better absorbed than saturated fatty acids, and medium-chain triglyceride better than long-chain triglyceride. Infants require 4–6 g fat/kg per day.

Considerable interest has developed in the role of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs) in milk and their role in brain development. LC-PUFAs are present in human but not bovine milk. As accumulation of fetal LC-PUFAs is increased up to five times in the last trimester, prematurely born infants are thought to be particularly at risk of deficiency. All ready-to-feed preterm formulas are supplemented with LC-PUFAs. The predominant polyunsaturated fats are omega-6 (linoleic acid) and omega-3 (alpha-linolenic acid [ALA]), which are required for production of arachidonic acid and docosahexanoic acid respectively.

Protein

Approximately 10% of the infant’s energy requirements is provided by protein. The recommended daily intake is 2.5–3.5 g/kg per day for full-term infants and 3.0–3.8 g/kg per day for very premature infants; ESPGHAN now recommend 4–4.5/kg per day for infants less than 1000 g. Milk protein is divided into curd (mainly casein) and whey (predominantly lactalbumin). Human milk contains more whey, and cows’ milk considerably more curd. There are also important differences in the amino acid profile of human and cows’ milk.

Minerals

The recommended minimal mineral requirements for optimal nutrition are shown in Table 9.3. In sick infants, particularly those receiving intravenous nutrition, it is important to monitor serum levels of these minerals and adjust intakes accordingly. Extra sodium may be required by the very-low-birthweight (VLBW) infant, as there may be a high urinary loss for the first weeks of life. Potassium should not be given until adequate renal function has been established.

Table 9.3 Recommended enteral intake of minerals for term and VLBW infants

Source: Koo and Tsang (1993).

| Enteral mineral intake (mmol/kg per day) | ||

| Term infant | VLBW infant | |

| Sodium | 2.5–3.5 | 3.0–4.0 |

| Potassium | 2.5–3.5 | 2.0–3.0 |

| Chloride | 5.0 | 1.5–4.5 |

| Phosphorus | 1.0–1.5 | 1.9–4.5 |

| Calcium | 1.2–1.5 | 3–5.5 |

| Magnesium | 0.6 | 0.3–0.6 |

Trace Elements

Recommended enteral requirements of trace elements are shown in Table 9.4. Copper and zinc have been shown to be essential trace elements for newborn infants. Other trace elements thought to be essential are chromium, manganese, iodine, cobalt and selenium. Breast milk and modern formula feeds contain some of these elements.

Table 9.4 Recommended daily enteral intake of some trace minerals

Source: Ehrenkranz (1993).

| Daily requirement | ||

| (mmol/kg) | (µg/kg) | |

| Zinc | 7.7–12.3 | 500–800 |

| Copper | 1.9 | 120 |

| Manganese | 0.01 | 0.75 |

| Chromium | 0.001 | 0.05 |

Iron

Both preterm and term infants born to healthy mothers have sufficient iron stores at birth to double their haemoglobin mass. Depletion of these stores occurs at 3 months in premature and 5 months in term infants. If the baby is not receiving adequate iron in the diet by this age, iron deficiency anaemia will develop. Although the iron content of breast milk declines from 0.6 mg/L at 2 weeks to 0.3 mg/L at 5 months, breast milk provides sufficient iron for a term infant up to 6 months of age. Preterm infants (irrespective of which milk they receive) should be monitored for iron deficiency anaemia and supplemented with oral iron if needed. Some units routinely provide iron supplement without the need for blood tests.

Vitamins

The daily vitamin requirements for the newborn and young infant are shown in Table 9.5. The fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K are stored in the body and large doses may result in toxicity. Excess doses of water-soluble vitamins are readily excreted. The preterm infant probably requires more vitamin D (1000 IU/day). This is discussed in the section on rickets of prematurity (see Chapter 20). There is no good evidence that routine supplementation with vitamin E prevents late anaemia, or bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Vitamin K is the only vitamin in which the normal breastfed infant may become seriously deficient; deficiency of this vitamin may cause haemorrhagic disease of the newborn (see Chapter 20). Despite controversies regarding the best dose and route of administration, all breastfed babies should be given vitamin K supplementation except for those who have already received intramuscular injection of vitamin K because of either their prematurity or sickness.

Table 9.5 Recommended daily dosage for vitamin supplementation

| Vitamin A | 500–1500 IU |

| Vitamin D | 400 IU |

| Vitamin E | 5 IU |

| Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) | 35 mg |

| Folate | 50 µg |

| Niacin | 5 mg |

| Riboflavin | 0.4 mg |

| Thiamine | 0.2 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.2 mg |

| Vitamin B12 | 1 µg |

| Vitamin K | 15 µg |

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding brings many benefits to both mother and baby (see Box 9.1).

- It provides a source of nutrition that changes with the baby’s changing metabolic needs

- It confers an advantage in intellectual attainment (see below)

- It is anti-infective (see below)

- It is antiallergic. The avoidance of foreign proteins in formula feeds reduces the risk of asthma and eczema in infants predisposed to these conditions

- It provides protection against various illnesses (e.g. gastroenteritis), although apparent protection against SIDS probably relates to maternal education, socioeconomic status and birthweight, rather than to breastfeeding per se

- Reduced likelihood and severity of cows’ milk protein allergy

- Decreased incidence of infant obesity and subsequently type 2 diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia

- Successful breastfeeding brings a sense of personal pride and achievement

- It promotes a close mother–baby relationship, which provides security, warmth and comfort to baby

- Lactation helps the mother lose weight acquired in pregnancy

- Convenience – there is no preparation of formula. Breast milk can also be simply expressed, stored and given to the baby by others

- Lactational amenorrhoea remains the world’s most important contraceptive by delaying the return of ovulation

- Oxytocin release during breastfeeding contracts the uterus and helps its involution

- Financial benefit, as breastfeeding does not cost

- It is possible to continue breastfeeding if a mother needs to return to paid work

- Breastfeeding confers some health advantages on the mother, as there appears to be some protection against ovarian and premenopausal breast cancer and osteoporosis

In 1991 UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the global baby-friendly hospital initiative to improve breastfeeding programmes. The ‘10 steps’ to successful breastfeeding are intended as a standard of good practice (Box 9.2).

Physiology of Lactation

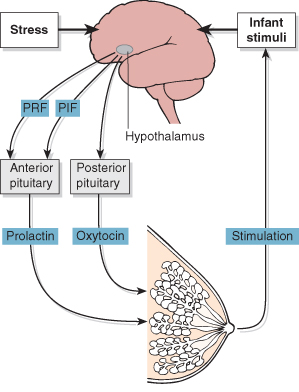

During pregnancy there is a marked increase in the number of ducts and alveoli within the breast in response to oestrogens, progesterone and placental lactogen. In the third trimester, prolactin secreted by the anterior pituitary sensitizes the glandular tissue with the secretion of small amounts of colostrum. The flow of milk after birth is under the control of the let-down reflex. The baby rooting at the nipple causes afferent impulses to pass to the posterior pituitary, which secretes oxytocin. This stimulates the smooth muscle fibres surrounding the alveoli to force the milk into the large ducts. After birth there is an increase in prolactin levels, which maintains milk production. The hormonal maintenance of lactation is summarized in Fig. 9.2.

Figure 9.2 Hormonal maintenance of lactation. PIF, prolactin inhibiting factor; PRF, prolactin releasing factor.

Stress inhibits oxytocin release and may reduce milk production. This may cause the baby to cry more, thereby heightening maternal stress and further inhibiting milk production. This may be an important factor in the failure of long-term lactation (see below).

Milk production is controlled by endogenous and exogenous factors:

- Endogenous (maternal) factors. In the first weeks of lactation, prolactin secretion occurs in response to feeding and controls milk production.

- Exogenous (baby) factors. After a few weeks of successful breastfeeding the baby exerts the major control on breast milk production. The amount of milk produced is related to effective and frequent removal of milk from the breast by the baby.

Nutritional Aspects

Human milk is uniquely adapted to the requirements of babies, with low levels of protein and minerals compared with the milks of other species. The energy content of human milk (67 kcal/100 mL) is provided by fat (54%), carbohydrate (40%) and protein (6%). Human milk has a very low protein content of only 0.9 g/100 mL, with a whey:casein ratio of 0.7. A larger proportion of the nitrogen in human milk is derived from non-protein sources compared with cows’ milk. Human milk contains twice as much lactalbumin as cows’ milk (and is immunologically different), but no lactoglobulin, which is a significant component of the protein constitution of cows’ milk. The levels of amino acids such as taurine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid and asparagine are especially high. Human milk fat is better absorbed than cows’ milk fat because of the smaller size of the emulsified fat globules and the presence of lipase in human milk

The main differences between human and cows’ milk are shown in Table 9.6. There is a higher proportion of unsaturated fatty acids and a lower proportion of saturated fatty acids in human milk than in cows’ milk. Human milk contains more vitamins A, C and E and nicotinic acid than does cows’ milk, but less vitamin B1, B2, B6, B12 and K. The low mineral level in human milk results in a low renal solute load for the immature kidney. Although calcium and phosphate levels in cows’ milk are higher than in human milk, their absorption from cows’ milk is much lower.

Table 9.6 Proteins in human milk and cows’ milk

Source: Reproduced from Hambraeus et al. (1984).

| Protein content (g/100 mL) | ||

| Human milk | Cows’ milk | |

| Total protein | ||