- Efficacy of breathing:

- chest expansion/abdominal excursion,

- breath sounds – reduced or absent, and symmetry on auscultation, and

- SpO2 in air.

- chest expansion/abdominal excursion,

- Effects of respiratory failure on other physiology:

- heart rate,

- skin colour, and

- mental status.

- heart rate,

Circulation

- Heart rate.

- Pulse volume.

- Capillary refill.

- Blood pressure.

- Skin temperature.

Disability

- Mental status/conscious level.

- Posture.

- Pupils.

Exposure

- Rash or fever.

- Cyanosis, not correcting with oxygen therapy

- Tachycardia out of proportion to respiratory difficulty

- Raised jugular venous pressure

- Gallop rhythm/murmur

- Enlarged liver

- Absent femoral pulses

8.5 RESUSCITATION OF THE CHILD WITH BREATHING DIFFICULTY

Airway

- A patent airway is the first requisite. If the airway is not patent, an airway-opening manoeuvre should be used.

- The airway should then be secured with a pharyngeal airway device or by intubation with experienced senior help.

Breathing

- All children with breathing difficulties should receive high-flow oxygen through a face mask as soon as the airway has been demonstrated to be adequate.

- Use a flow of 10–15 L/min via a face mask and reservoir bag to provide the child with 100% oxygen. If lower flows maintain adequate SpO2 (i.e. 94–98%), then nasal cannulae or nasopharyngeal catheters may be used (at rates of <2 L/min).

- If the child is hypoventilating with a slow respiratory rate or weak effort, respiration should be supported with oxygen via a bag–valve–mask device and experienced senior help summoned.

Circulation

Fluid intake may have been reduced, particularly in infants presenting with breathing difficulties. Consider a fluid bolus (20 mL/kg of 0.9% saline) if there are signs of circulatory failure and particularly when intubation and positive pressure ventilation is initiated. Be aware that respiratory illnesses can cause antidiuretic hormone secretion, leading to fluid retention, so maintenance fluids may need to be reduced to two-thirds normal. Although this strategy does not prevent the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), it reduces the risk from fluid administration. Sufficient fluid should be administered to remain euvolaemic.

8.6 SECONDARY ASSESSMENT AND LOOKING FOR KEY FEATURES OF THE CHILD WITH BREATHING DIFFICULTIES

While the primary assessment and resuscitation are being carried out, a focused history of the child’s health and activity over the previous 24 hours and any significant previous illness should be gained.

All children with breathing difficulties will have varying degrees of respiratory distress and cough, so these are not useful diagnostic discriminators.

Certain key features, which will be identified clinically in the above assessment and from the focused history, can point the clinician to the likeliest working diagnosis for emergency treatment.

| • Inspiratory noises, i.e. stridor, point to upper airway obstruction | Section 8.7 |

| • Expiratory noises, i.e. wheeze, point to lower airway obstruction | Section 8.8 |

| • Fever without stridor suggests pneumonia | Section 8.9 |

| • Signs of heart failure point to congenital or acquired heart disease | Section 8.10 |

| • Short history, exposure to allergen and urticarial rash point to anaphylaxis | Section 9.10 |

| • Suspicion of ingestion and absence of cardiorespiratory pathology point to poisoning | Section 8.12 |

8.7 APPROACH TO THE CHILD WITH STRIDOR

Obstruction of the upper airway (larynx and trachea) is potentially life-threatening. The small cross-sectional area of the upper airway renders the young child particularly vulnerable to obstruction by oedema, secretions or an inhaled foreign body (Table 8.2).

Table 8.2 Causes of stridor.

| Incidence | Diagnosis | Clinical features |

| Very common | Viral croup (laryngotracheobronchitis) | Coryzal, barking cough, mild fever, hoarse voice |

| Common | Spasmodic (recurrent) croup | Sudden onset, recurrent, history of atopy |

| Laryngomalacia | Systematically well with variable stridor | |

| Uncommon | Laryngeal foreign body | Sudden onset, history of choking |

| Rare | Epiglottitis | Drooling, muffled voice, septic appearance |

| Bacterial tracheitis | Harsh cough, chest pain, septic appearance | |

| Trauma | Neck swelling, crepitus, bruising | |

| Retropharyngeal abscess | Drooling, septic appearance | |

| Inhalation of hot gases | Facial burns, perioral soot | |

| Infectious mononucleosis | Sore throat, tonsillar enlargement | |

| Angioneurotic oedema | Itching, facial swelling, urticarial rash | |

| Diphtheria | Travel to endemic area, unimmunised |

Reassess Airway

Is the airway partially obstructed or narrowed and what is the likely cause? Note the presence of inspiratory noises.

- If ‘bubbly’ noises are heard, the airway may be full of secretions requiring clearance. This also suggests that the child is either very fatigued, or has a depressed conscious level and cannot clear the secretions him- or herself by coughing.

- If stertorous (snoring) respiratory noises are heard, consider partial obstruction of the airway due to a depressed conscious level.

- If there is a harsh stridor associated with a barking cough, upper airway obstruction due to croup should be suspected.

- If a quiet stridor in a sick-looking child is present, consider epiglottitis.

- With a very sudden onset, no prodromal symptoms and a history suggestive of inhalation, consider a laryngeal foreign body.

Airway Emergency Treatment

Reassess the breathing: what degree of effort is needed for breathing and what is its efficacy and effect? The answer to this question will inform the clinician as to the severity of the upper airway obstruction. A pulse oximeter should be attached and the oxygen saturation noted both on breathing air and high-flow oxygen.

Partial Obstruction From Secretions or a Depressed Conscious Level

- Use suction to clear an airway partially obstructed by secretions as long as there is no stridor.

- Support the airway with the chin lift or jaw thrust manoeuvre in a child with stertorous breathing due to a depressed conscious level or extreme fatigue and seek urgent help with advanced airway skills.

- Further maintenance of the airway can be accomplished with an oro- or nasopharyngeal airway, but the child may require intubation.

- Whilst help is summoned, support breathing with bag–mask ventilation and high-flow oxygen

Management of Stridor

The immediate management of stridor will depend on the severity of obstruction, degree of respiratory difficulty and the most likely cause. The specific management for each of these upper airway emergencies is listed below.

Croup

Background

Croup is defined as an acute clinical syndrome with stridor, a barking cough, hoarseness and variable degrees of respiratory distress. This definition embraces several distinct disorders. Acute viral laryngotracheobronchitis (viral croup) is the commonest form of croup and accounts for over 95% of laryngotracheal infections. Parainfluenza viruses are the commonest pathogens but other respiratory viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus and adenoviruses, produce a similar clinical picture. The peak incidence of viral croup is in the second year of life and most hospital admissions are in children aged between 6 months and 5 years.

The typical features of a barking cough, harsh stridor and hoarseness are usually preceded by fever and coryza for 1–3 days. The symptoms often start, and are worse, at night. Many children have stridor and a mild fever (<38.5°C), with little or no respiratory difficulty. If tracheal narrowing is minor, stridor will be present only when the child hyperventilates or is upset. As the narrowing progresses, the stridor becomes both inspiratory and expiratory, and is present even when the child is at rest. Some children, and particularly those below the age of 3 years, develop the features of increasing obstruction and hypoxia with marked sternal and subcostal recession, tachycardia, tachypnoea and agitation. If the infection extends distally to the bronchi, wheeze may also be audible.

Some children have repeated episodes of croup without preceding fever and coryza. The symptoms are often of sudden onset at night, and usually persist for only a few hours. This recurrent or spasmodic croup may be associated with atopic disease (asthma, eczema, hayfever). The episodes can be severe, but are more commonly self-limiting. They are difficult to distinguish clinically from infectious croup and appear to respond identically to treatment, so there is a case for considering both conditions as part of one spectrum of disease.

Emergency Management of Croup

- Children with croup who have stridor or difficulty breathing should receive a stat dose of oral dexamethasone (0.15 mg/kg). Although not quite as effective, prednisolone (1 mg/kg) is a reasonable alternative.

- Children with severe respiratory distress should receive nebulised adrenaline (0.5 mL/kg of 1 : 1000 up to a maximum of 5 mL) with oxygen through a face mask. This will produce produce an improvement beginning within minutes and lasting for up to 2 hours. It may need to be repeated, and if so, additional measures should be taken to ensure the airway is managed by senior staff.

- Children who have received adrenaline will appear improved for a short while only and need to be observed and monitored closely. They may later require tracheal intubation. A marked tachycardia is usually produced by the adrenaline, but other side effects are uncommon.

- Steroids modify the natural history of croup. They give rise to some clinical improvement within 30 minutes and may lead to a reduction in hospital stay, need for intubation, duration of intubation and need for re-intubation in children with severe croup. Generally, dexamethasone (0.15 mg/kg) is given. Higher doses of dexamethasone, administered systemically, are sometimes used if there is severe obstruction. Alternatives include nebulised budesonide 2 mg or prednisolone 1 mg/kg.

- Give oxygen through a face mask, and monitor the oxygen saturation.

- Inhalation of warm humidified air is of unproven benefit.

Fewer than 5% of children admitted to hospital with croup require tracheal intubation. The decision to intubate is a clinical one based on increasing tachycardia, tachypnoea and chest retraction, or the appearance of cyanosis, exhaustion or confusion. Ideally, the procedure should be performed under inhalational anaesthetic by an experienced paediatric anaesthetist, unless there has been a respiratory arrest. A much smaller gauge tracheal tube than usual is often required. If there is doubt about the diagnosis, or difficulty in intubation is anticipated, an ENT surgeon capable of performing a tracheotomy should be present. The median duration of intubation in croup is 3 days; the younger the child, the longer the intubation that is usually required. All intubated children must have continuous carbon dioxide and SpO2 monitoring.

Laryngomalacia

Background

Laryngomalacia is a congenital abnormality of the larynx, specifically the supraglottic structures, with collapse on inspiration causing stridor in infancy. Tracheomalacia refers to a similar collapse of a compliant trachea. Stridor is variable in intensity and intermittent in nature, but is often worse during upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). The stridor (‘noisy breathing’) is usually present from a young age; hoarseness is usually absent. The diagnosis is often suspected by history and examination, but proven by laryngo-bronchoscopy. In most infants the condition is mild and improves with growth. Concurrent gastro-oesophageal reflux should be treated. Review by an ENT specialist and investigation depends upon the severity of the symptoms. A small number of patients may require surgical intervention.

Emergency Management of Laryngomalacia

Most infants require no specific treatment. If there is severe distress then supplemental oxygen should be provided. Infants with an intercurrent URTI and severe distress may benefit from nebulised adrenaline. Mask continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) may also help if there is marked respiratory difficulty and recession.

Foreign Body

Background

The inquisitive and fearless toddler and the infant with toddler siblings are at risk of inhaling a foreign body. If an inhaled foreign body lodges in the larynx or trachea the outcome is often fatal at home, unless measures such as those discussed in Chapter 4 are performed.

Should a child present to hospital with very sudden onset of stridor and other signs of acute upper airway obstruction, especially during waking hours, and particularly if there is no fever or preceding illness, then a laryngeal foreign body is the likely diagnosis. A history of eating or of playing with small objects immediately prior to the onset of symptoms is strong supportive evidence. Foodstuffs (nuts, sweets, meat) are the commonest offending items.

In some instances, objects may compress the trachea from their position of lodgement in the upper oesophagus, producing a similar but less severe picture of airway obstruction. The object may pass through the larynx into the bronchial tree, where it produces a persistent cough of very acute onset, and unilateral wheezing.

Examination of the chest may reveal decreased air entry on one side or evidence of a collapsed lung. Inspiratory and expiratory chest radiographs may show a mediastinal shift on expiration due to gas trapping distal to the bronchial foreign body. Other radiographic techniques to demonstrate gas trapping are sometimes used as it may be difficult to catch inspiration and expiration with rapid respiration. Techniques include an anteroposterior (AP) decubitus film. This film is taken with the infant lying on the side, with the suspected side down, the X-ray plate behind and the X-ray beam traversing AP. The dependent lung would normally appear more radio-opaque (whiter) but if hyperinflated will be more radiolucent (blacker) than the other lung. The same technique can be used to identify small pneumothoraces, but with the suspected side up.

Emergency Management of an Airway Foreign Body

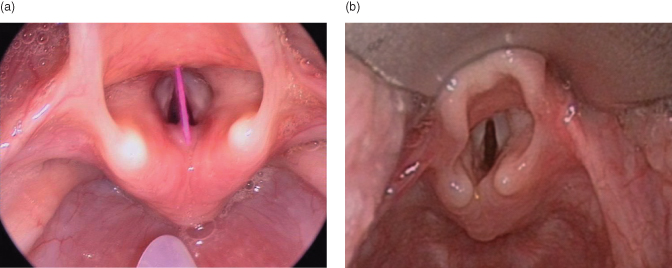

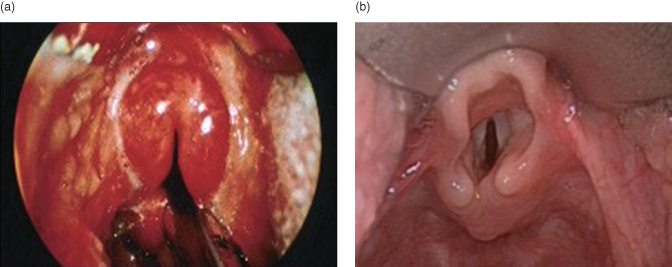

- In extreme cases of threat to life (complete obstruction and apnoea), immediate direct laryngoscopy with Magill forceps to remove a visible foreign body (Figure 8.1) may be necessary.

- Urgent laryngoscopy (generally in an operating theatre) will be needed for children with severe respiratory distress and a significant history of foreign body inhalation if the ‘choking child’ procedure (see Chapter 4) has been unsuccessful.

- Do not jeopardise the airway by unpleasant or frightening interventions, but contact a senior anaesthetist/ENT surgeon urgently.

Removal through a bronchoscope under general anaesthetic should be performed as soon as possible because there is a risk that coughing will move the object into the trachea and cause life-threatening obstruction. In the case of a stridulous child with a relatively stable airway and a strong suspicion of foreign body inhalation, general anaesthesia can be used, usually by gaseous induction by an experienced anaesthetist, with the presence of an ENT surgeon to perform a tracheotomy in case of deterioration. The foreign body can then be removed under controlled conditions. In some cases, prior to anaesthesia, it may be appropriate to perform a careful lateral neck radiograph in the emergency room (taking extreme care not to distress the child, which might provoke complete obstruction) to ascertain the position and nature of the object.

Epiglottitis

Background

Acute epiglottitis shares some clinical features with croup but it is a quite distinct entity. Although much less common than croup, its importance is that unless the diagnosis is made rapidly and appropriate treatment commenced, total obstruction and death are likely to ensue. This is far less commonly seen in countries where Haemophilus influenzae B (Hib) immunisation is routine, but may still occur in cases of vaccine failure and in unimmunised children.

Infection with Hib or other pathogens causes intense swelling of the epiglottis and the surrounding tissues and obstruction of the larynx. Epiglottitis is most common in children aged 1–6 years, but it can occur in infants and in adults.

The onset of the illness is usually acute with high fever, lethargy, a soft inspiratory stridor and rapidly increasing respiratory difficulty over 3–6 hours. In contrast to croup, cough is minimal or absent. Typically the child sits immobile, with the chin slightly raised and the mouth open, drooling saliva. They look very toxic and may be pale with poor peripheral circulation. There is usually a high fever (>39°C). Because the throat is so painful, the child is reluctant to speak and unable to swallow drinks or saliva.

Emergency Management of Epiglottitis

- Intubation is likely to be required. Contact a senior anaesthetist urgently, who will perform a careful gaseous induction of anaesthesia. When deeply anaesthetised, the child can be laid on his back to allow laryngoscopy and intubation. Tracheal intubation may be difficult because of the intense swelling and inflammation of the epiglottis (‘cherry red epiglottis’, Figure 8.2). A smaller tube than the one usually required for the child’s size will be necessary.

- Do not jeopardise the airway by unpleasant or frightening interventions. Do not lie the child down if he or she prefers sitting up.

- Interventions, such as lateral radiographs of the neck and venepuncture, should be avoided as they disturb the child and have precipitated fatal total airway obstruction.

- There is no evidence that nebulised adrenaline or steroids are beneficial.

Figure 8.2 (a) Larynx epiglottitis, and (b) normal larynx.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree