- Efficacy of breathing:

- chest expansion/abdominal excursion,

- breath sounds – reduced or absent, and symmetry on auscultation, and

- SpO2 in air.

- chest expansion/abdominal excursion,

- Effects of respiratory failure on other physiology:

- heart rate,

- skin colour, and

- mental status.

- heart rate,

Circulation

- Heart rate: this is the defining observation for this presentation. An abnormal pulse rate is defined as one falling outside the normal range given in Chapter 2. In practice, most serious disease or injury states are associated with a sinus tachycardia. In infants this may be as high as 220 beats per minute (bpm) and in children up to 180 bpm. Rates over these figures are highly likely to be tachyarrhythmias, but in any case of significant tachycardia (i.e. 200 bpm in an infant and 150 bpm in a child) an electrocardiogram (ECG) rhythm strip should be examined and, if in doubt, a full 12-lead ECG performed. Very high rates may be impossible to count manually and the pulse oximeter is often unreliable in this regard. Again, a rhythm strip is advised.

An abnormally slow pulse rate is defined as one less than 60 bpm or a rapidly falling heart rate associated with poor systemic perfusion. This will almost always be in a child who requires major resuscitation.

- Pulse volume.

- Blood pressure.

- Capillary refill.

- Skin temperature.

Disability

- Mental status/conscious level.

- Posture.

- Pupils.

Exposure

- Rash or fever.

10.3 RESUSCITATION

Airway

If the airway is not open, use one of the following:

- An airway-opening manoeuvre.

- An airway adjunct.

- Urgent induction of anaesthesia followed by intubation to secure the airway.

Breathing

- Give high-flow oxygen through a face mask with a reservoir as soon as the airway has been shown to be adequate.

- If the child is hypoventilating or has bradycardia, respiration should be supported with oxygen via a bag–valve–mask device and consideration given to intubation and ventilation.

Circulation

- If there is shock and the heart rate is <60 bpm, start chest compressions.

- If there is shock and the ECG shows ventricular tachycardia (VT), give up to one or two synchronous electric shocks at 1 and 2 J/kg:

- the child who is responsive to pain should be anaesthetised or sedated first,

- if the synchronous shocks for VT are ineffectual (because the defibrillator cannot recognise the abnormally shaped QRS complex), then the shocks may have to be given asynchronously, recognising that this is a more risky procedure – because without conversion the rhythm may deteriorate to ventricular fibrillation (VF) or asystole, and

- synchronisation relies on the ability of the defibrillator to recognise the QRST complex, and is designed to avoid shock delivery at a point in the cardiac cycle likely to precipitate VF.

- the child who is responsive to pain should be anaesthetised or sedated first,

- Gain intravenous or intraosseous access.

- If the tachyarrhythmia is supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) then give intravenous/intraosseous adenosine, if this can be administered more quickly than a synchronous electric shock. Use 0.1 mg/kg IV, increase after 2 minutes if necessary to 0.2 mg/kg and then 0.3 mg/kg to a maximum single dose of 500 micrograms/kg (300 micrograms/kg if the baby is aged under 1 month).

- Take blood for full blood count, renal function, bedside glucose test and glucose laboratory test.

- Give a bolus of 20 mL/kg IV crystalloid to a patient with bradycardia who is in shock.

While the primary assessment and resuscitation are being carried out, a focused history of the child’s health and activity over the previous 24 hours should be gained. Certain key features that will be identified clinically in the primary assessment – from the focused history, from the initial blood tests and from the rhythm strip and 12-lead ECG – can point the clinician to the likeliest working diagnosis for emergency treatment.

From the ECG the arrhythmia can be categorised by the following simple questions:

Bradycardia

- Bradycardia is usually a pre-terminal rhythm. It is seen as the final response to profound hypoxia and ischaemia and its presence is ominous.

- Bradycardia is precipitated by vagal stimulation as occurs in tracheal intubation and suctioning and may be found in postoperative cardiac patients. The rhythm is usually irregular.

- Bradycardia may be seen in children with raised intracranial pressure. These patients will have presented with decreased conscious level and their management can be found in Chapters 11 and 16.

- Bradycardia can be a side effect of poisoning with digoxin or β-blockers and the management can be found in Appendix H.

Tachyarrhythmia

- Tachyarrhythmia with a narrow QRS complex on the ECG is usually SVT. The rhythm is usually regular.

- Tachyarrhythmia with a wide QRS complex on the ECG is usually VT; this can be provoked by:

- hyperkalaemia, or

- poisoning with tricyclic antidepressants. Additional details on the management of the poisoned child with VT can be found in Appendix H.

- hyperkalaemia, or

10.4 APPROACH TO THE CHILD WITH BRADYCARDIA

In paediatric practice bradycardia is almost always a pre-terminal finding in patients with respiratory or circulatory insufficiency. Airway, breathing and circulation should always be assessed and treated if needed before pharmacological management of bradycardia.

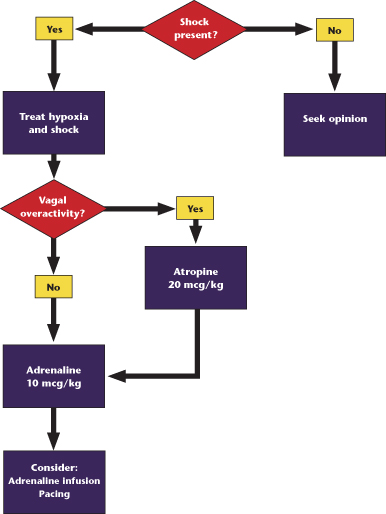

Emergency Treatment of Bradycardia (Figure 10.1)

- Reassess ABC.

- If there is hypoxia and shock, treat with:

- high-concentration oxygen, bag–mask ventilation, intubation and intermittent positive pressure ventilation, and

- volume expansion (20 mL/kg of 0.9% saline repeated as recommended in the treatment of shock).

- high-concentration oxygen, bag–mask ventilation, intubation and intermittent positive pressure ventilation, and

- If the above is ineffective give a bolus of adrenaline 10 micrograms/kg IV.

- If the above is ineffective try an infusion of adrenaline 10 nanograms/kg/min to 5 mcg/kg/min IV.

- If there has been vagal stimulation:

- treat with adequate ventilation,

- give atropine 20 micrograms/kg IV/IO (minimum dose 100 micrograms; maximum dose 600 micrograms),

- the dose may be repeated after 5 minutes (maximum total dose of 1.2 mg) and

- if IV/IO access is unavailable, atropine (0.04 mg/kg) may be administered tracheally, although absorption into the circulation may be unreliable.

- treat with adequate ventilation,

- If there has been poisoning, seek expert toxicology help.

Figure 10.1 Algorithm for the management of bradycardia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree