Efficacy of Breathing

Observations of the degree of chest expansion (or, in infants, abdominal excursion) provide an indication of the amount of air being inspired and expired. Similarly, important information is given by auscultation of the chest. Listen for reduced, asymmetrical or bronchial breath sounds. A silent chest is an extremely worrying sign.

Pulse oximetry can be used to measure the arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2). A good plethysmographic (pulse) wave form is important to help confirm the accuracy of measurements. In severe shock and hypothermia, there may be poor or absent pulse detection. Measurements are also less accurate when the SpO2 is less than 70%, with motion artefact, high levels of ambient light and in the presence of carboxyhaemoglobin. Oximetry in air gives a good indication of the efficacy of breathing, although to assess the adequacy of ventilation some measure of carbon dioxide would be required. Supplemental oxygen will mask low SpO2 due to ineffective breathing unless the hypoxia is severe. Normal SpO2 in an infant or child at sea level is 97–100%.

Effects of Respiratory Inadequacy on Other Organs

Heart Rate

Hypoxia produces tachycardia in the older infant and child. Anxiety and a fever will also contribute to tachycardia, making this a non-specific sign. Severe or prolonged hypoxia leads to bradycardia. This is a pre-terminal sign.

Skin Colour

Hypoxia (via catecholamine release) produces vasoconstriction and skin pallor. Cyanosis is a late and pre-terminal sign of hypoxia as it usually appears when SpO2 falls to <70%, and only in the absence of anaemia. By the time central cyanosis is visible in acute respiratory disease, the child is close to respiratory arrest. In the anaemic child, cyanosis may never be visible despite profound hypoxia. A few children will be cyanosed because of cyanotic heart disease, but may have adequate oxygen delivery. Their cyanosis will be largely unchanged by oxygen therapy.

Mental Status

The hypoxic or hypercapnic child will be agitated and/or drowsy. Gradually drowsiness increases and eventually consciousness is lost. These important signs are often more difficult to detect in small infants. The parents may say that the infant is just ‘not himself’. Assess the child’s state of alertness by gaining eye contact and noting the response to voice and, if necessary, to painful stimuli. A generalised muscular hypotonia also accompanies hypoxic cerebral depression.

7.3 PRIMARY ASSESSMENT OF CIRCULATION

Recognition of Potential Circulatory Failure

The cardiovascular status needs to be assessed bearing in mind the effects of circulatory inadequacy on other organs.

Cardiovascular Status

Heart Rate

Normal rates are shown in Table 7.2. The heart rate initially increases in shock due to catecholamine release and as compensation for decreased stroke volume. The rate, particularly in small infants, may be extremely high (up to 220 beats per minute).

Table 7.2 Heart rate at rest by age.

| Age (years) | Heart rate (beats/min) |

| <1 | 110–160 |

| 1–2 | 100–150 |

| 2–5 | 95–140 |

| 5–12 | 80–120 |

| >12 | 60–100 |

An abnormally slow pulse rate, or bradycardia, is defined as less than 60 beats per minute or a rapidly falling heart rate associated with poor systemic perfusion. This is a pre-terminal sign.

Pulse Volume

Although blood pressure is maintained until shock is severe, an indication of perfusion can be gained by comparative palpation of both the peripheral and central pulses. Absent peripheral pulses and weak central pulses are serious signs of advanced shock, and indicate that hypotension is already present. Bounding pulses may be caused by an increased cardiac output (e.g. septicaemia), arteriovenous systemic shunt (e.g. patent arterial duct) or hypercapnia.

Capillary Refill

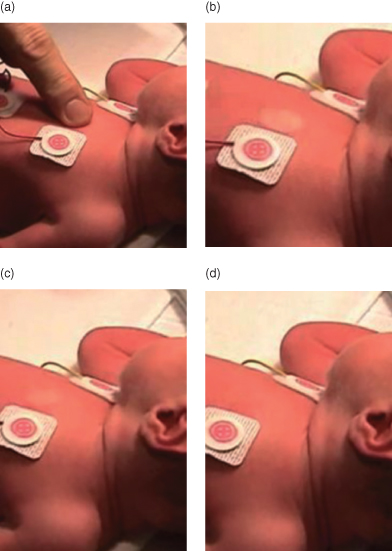

Following cutaneous pressure on the centre of the sternum or on a digit for 5 seconds, capillary refill should occur within 2 seconds (Figure 7.1). A slower refill time than this can indicate poor skin perfusion, a sign which may be helpful in early septic shock when the child may otherwise appear well, with warm peripheries.

Figure 7.1 (a–d) Capillary refill assessment: apply pressure for 5 seconds and then release. Count in seconds how long it takes for the skin colour to return to normal.

The presence of fever does not affect the sensitivity of delayed capillary refill in children with hypovolaemia but a low ambient temperature reduces its specificity, so the sign should be used with caution in trauma patients who have been in a cold environment. Poor capillary refill and differential pulse volumes are neither sensitive nor specific indicators of shock in infants and children, but are useful clinical signs when used in conjunction with the other signs described. They should not be used as the only indicators of shock nor as quantitative measures of the response to treatment.

Blood Pressure

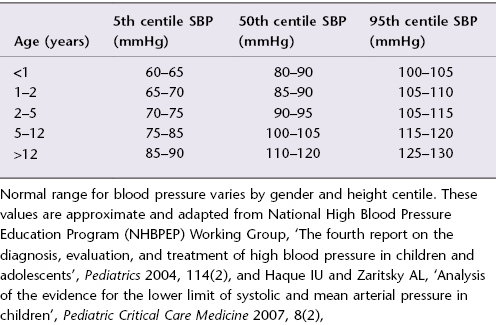

Normal systolic pressures are shown in Table 7.3. Expected systolic blood pressure (BP) for the 50th centile can be estimated by the following formula: BP = 85 + (age in years × 2). Use of the correct cuff size is crucial if an accurate blood pressure measurement is to be obtained. This caveat applies to both auscultatory and oscillometric devices. The widest cuff that will fit on the child’s upper arm should be used.

Table 7.3 Systolic blood pressure (SBP) at rest by age.

Hypotension is a late and pre-terminal sign of circulatory failure. Once a child’s blood pressure has fallen, cardiac arrest is imminent. Hypertension can be the cause or result of coma and raised intracranial pressure.

Effects of Circulatory Inadequacy on Other Organs

Respiratory System

A rapid respiratory rate with an increased tidal volume, but without recession, may be caused by the metabolic acidosis resulting from circulatory failure.

Skin

Mottled, cold, pale skin peripherally indicates poor perfusion. A line of coldness may move centrally as circulatory failure progresses.

Mental Status

Agitation and then drowsiness leading to unconsciousness are characteristic of circulatory failure. These signs are caused by poor cerebral perfusion. In an infant, parents may say that he is ‘not himself’.

Urinary Output

A urine output of less than 1 mL/kg/h in children and less than 2 mL/kg/h in infants indicates inadequate renal perfusion during shock. A history of oliguria or anuria should be sought.

Cardiac Failure

The following features suggest a cardiac cause of respiratory inadequacy:

- Cyanosis, not correcting with oxygen therapy.

- Tachycardia out of proportion to respiratory difficulty.

- Raised jugular venous pressure.

- Gallop rhythm/murmur.

- Enlarged liver.

- Absent femoral pulses.

7.4 PRIMARY ASSESSMENT OF DISABILITY

Recognition of Potential Central Neurological Failure

Neurological assessment should only be performed after airway (A), breathing (B) and circulation (C) have been assessed and treated. There are no neurological problems that take priority over ABC.

Both respiratory and circulatory failure will have central neurological effects. Conversely, some conditions with direct central neurological effects (such as meningitis, raised intracranial pressure from trauma, and status epilepticus) may also have respiratory and circulatory consequences.

Neurological Function

Conscious Level

A rapid assessment of conscious level can be made by assigning the child to one of the categories shown in the box.

If the child does not respond to voice, it is important that an assessment of the response to pain follows. The painful central stimulus can be delivered by sternal pressure, by supraorbital ridge pressure or by pulling frontal hair. A child who is unresponsive or who only responds to pain has a significant degree of coma, equivalent to 8 or less on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).

If the child responds to pain, it is best to note what the eyes and limbs did and what sounds or words were uttered, rather than simply categorising the child as ‘P’. Simple descriptions that will form the basis of a subsequent formal GCS assessment, such as ‘opening eyes to pain’ or ‘localising to pain’ are much more informative than ‘P’ alone. A child who does not open his eyes to pain, utters no sounds and extends his limbs has a GCS score of 4 and is likely to need prompt airway protection. A child who opens her eyes to pain, shouts recognisable words inappropriately and localises to the stimulus has a GCS score of 10 and is at much less immediate risk. Both are classified as ‘P’.

Posture

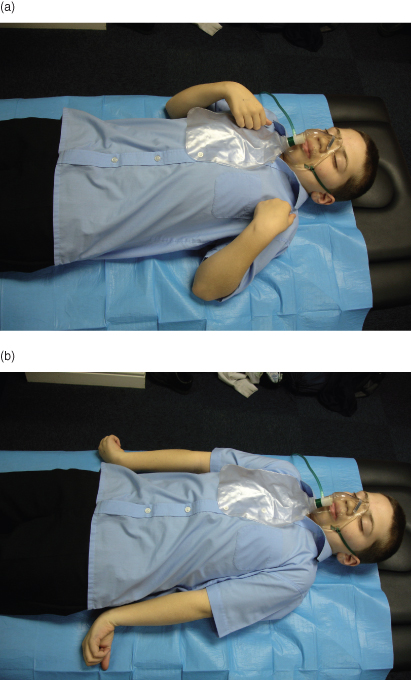

Many children who are suffering from a serious illness in any system are hypotonic. Stiff posturing such as that shown by decorticate (flexed arms, extended legs) or decerebrate (extended arms, extended legs) children is a sign of serious brain dysfunction (Figure 7.2). These postures can be mistaken for the tonic phase of a convulsion. Alternatively, a painful stimulus may be necessary to elicit these postures. Severe extension of the neck due to upper airway obstruction can mimic the opisthotonos that occurs with meningeal irritation. A stiff neck and full fontanelle in infants are signs that suggest meningitis.

Figure 7.2 (a) Decorticate posturing, and (b) decerebrate posturing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree