Summary and recommendations for research and practice

- Developing countries are faced with the double burden of malnutrition. However, as income rises, the problem of obesity becomes progressively more important.

- In most developing countries there is no net food energy shortage, but limited access to healthier foods, which are more expensive, and this defines consumption patterns.

- Poverty is often associated with obesity; increased consumption of low-cost energy-dense foods and decreased physical activity are the main causes.

- In transitional societies, foods provided by government feeding programs to stunted children may contribute to rising obesity rates.

- Micronutrient-rich foods with no excess of energy should be provided to stunted children early on, to promote linear growth, lean body mass gain and prevent later obesity.

The double burden of malnutrition

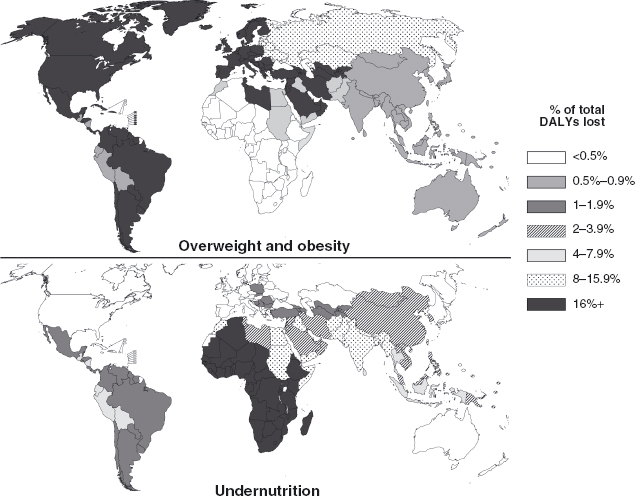

Undernutrition is no longer the dominant form of human malnutrition from the standpoint of population public health relevance. The coexistence of the dual expressions of under- and overnutrition are now apparent globally: in 2001, the estimated number of people worldwide suffering from overweight equaled those with undernutrition. Close to a billion people were estimated to be overweight or obese and an equal number who were underweight, with the former being predominantly adults in developed countries and the latter being predominantly children in developing countries.1–6 Figure 33.1 shows how overweight and obesity coexist with underweight; the global geographic distribution maps show the proportion of healthy life years lost from conditions related to excess and insufficient energy intake relative to expenditure.

Figure 33.1 Global geographic distribution maps of the proportion of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) burden from conditions related to excess energy (overweight and obesity) in the upper panel and DALYs burden related to undernutrition (underweight) in the lower panel. (Adapted from R Uauy, The role of the international community forging a common agenda in tackling the double burden of malnutrition. SCN News #32, 2006).

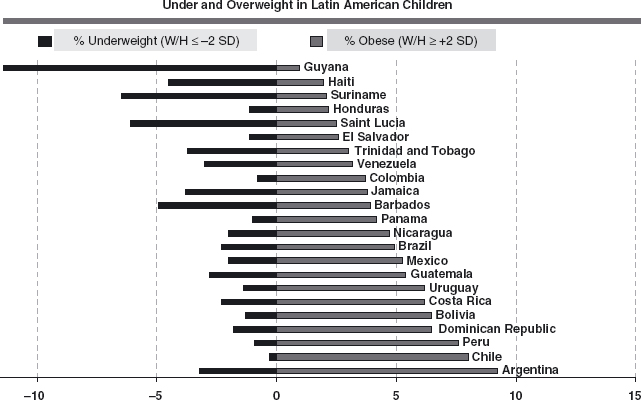

There is clearly a need for a common agenda to address the double burden as in some regions, such as Northern Africa and the Middle East, most of South, Southeast and East Asia, there is an appreciable loss of disability-adjusted life year s (DALY s) from both conditions. In Europe and most of the Americas the problem is largely related to obesity. The double burden existing within the same nation is the next level of aggregation in a descending hierarchy. De Onis4,7,8 has provided a perspective on how under- and overnutrition operate within the same countries, specifically with reference to children. The percentages of children in different Latin American nations who are underweight and overweight relative to the international reference median are shown in Figure 33.2. However, this graph needs to be interpreted in the light of the cut-off standards used. At each end of a Gaussian distribution, 2.5% of any reference population would, itself, have values beyond 2 standard deviations. In this respect, the burden is only dual on a population basis where the prevalence in both directions exceeds >2.5% on the horizontal axis. Guyana and Haiti are the countries with a single burden of undernutrition. For most of the other nations a greater burden is caused by energy excess, indicating that overweight has emerged as the dominant malnutrition problem even in this young age group.9,10

Figure 33.2 The percentage of children in Latin American nations with weight-for-height Z-scores either below (underweight) or above (obese) 2 standard deviations of the international reference WHO standard. The obesity figures are likely underestimates considering the present WHO 2006 reference in terms of obesity. (Adapted from De Onis 8).

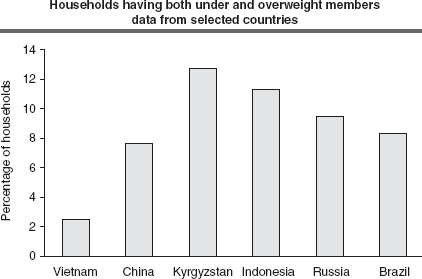

De Onis and Blossner4 conclude that, “attention should be paid to monitoring levels and trends of overweight in children. This, however, should not be done at the expense of decreasing international commitments to alleviating undernutrition.” Within the same community or even within a given household, the presence of both over- and undernutrition takes on some interesting dimensions. Caballero11 has scrutinized the phenomenon of persons with high and low body weights living in the same household; the findings are summarized in Figure 33.3. On a continuum of gross national product, only the poorest countries have a low rate of the intra-household dual burdens; this is partly explained by the low prevalence of obesity limiting the opportunity for association. However, as incomes rise, one can observe the curious occurrence of a mixture of the extremes of body composition status existing within the same family unit.

Figure 33.3 Percent of households having individuals with high- and low-body weights in the same household. As gross national product increases the intra-household dual burdens also increases. (Adapted from Caballero11).

Finally, within a given individual, namely a mal-nourished young child, there can be a quick transition, over a few years or even months, from being wasted (underweight for height) to being overweight or even obese (excess weight for height). Moreover, in many cases, these children remain stunted (low height for age), making them more vulnerable in an urban setting to obesity and diabetes, both of which are linked to excess body fat resulting from sedentary lifestyles and consumption of high-energy density diets. In fact, the model of the malnourished child during recovery serves to illustrate many of the features of the nutrition transition mirroring the rapid shift in diet from low- to high-energy density food, as well as a progressively sedentary life style, that moves stunted populations from underweight to overweight and obesity.12

More recently, the influence of postnatal growth on later development of obesity and nutrition-related chronic disease has been documented. Postnatal growth is clearly related to prenatal growth with some of the metabolic changes associated with prenatal nutritional sufficiency affecting postnatal physiology and behavior which, in turn, affect growth.13–15 In 2005, Stein et al reviewed the evidence linking child growth and chronic diseases in five cohorts from transitional countries (China, India, Guatemala, Brazil and the Philippines) concluding that growth failure in early childhood and increased weight gain in later childhood were associated with increased prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease (i.e. body composition, blood pressure, glucose metabolism).16 These results correspond to studies from cohorts that originated in the 1970s and early 1980s. The clear progression of the obesogenic environment in most countries around the world suggests that the present impact of these early life factors in determining the rise in adult chronic diseases is likely to be underestimated.

Postnatal growth, on the other hand, is also associated with later adult disease independent of prenatal growth. Studies from developed countries show a consistent positive association between infant size and later body size but inconsistent associations with later disease.17 In transitional countries, it is important to clarify the relative importance of growth in different postnatal periods in order to implement interventions. In Brazil, India and Guatemala, growth in infancy (0–1 years) and late childhood (over 2 years) were described as critical periods predicting adult body composition. Weight gain in infancy was related to higher fat-free mass in adulthood, while rapid weight gain in late childhood was associated with a higher acquisition of fat mass. In India, greater increases in body mass index (BMI) between 2 and 12 years were strongly associated with glucose intolerance and Type 2 diabetes in adulthood.15

Access to food, poverty and childhood obesity

Income level is the main determinant of access to food. The proportion of family income that is spent on food serves to define the population income categories in most developing countries. If family income is less than the cost of one basic food basket the family is defined as indigent; those with income below the cost of two food baskets are classified as poor, in this case they actually spend more than 50% of their income on basic foods.18

Food security depends on the households’ access to food rather than overall availability of food. In rural areas, household food security depends mainly on access to land and other agricultural resources which facilitate domestic production. In urban areas, however, food is mainly purchased in the market. A variety of foods, therefore, needs to be available and affordable in urban markets for adequate food security. In most developing regions there is plenty of food in the stores, yet families living under poverty conditions are unable to buy food of sufficient quantity and/or quality and thus will be food insecure.19,20

Poverty and food insecurity go hand in hand. Food security in poor households often fluctuates dramatically, depending on changes in agricultural production in response to seasonal and environmental conditions. Fluctuating market prices affect poor producers as well as the urban or rural poor. In an open market economy, farmers and their families are also affected by falling global market prices for food commodities. In most cases, they depend on products they place in the market and this means that their income will vary with commodity prices which are beyond their control. In the urban setting, the poor rely on food purchases that are commonly affected by rampant inflation. This income instability means that families may be able to cope with their food bills for one week, but are unsure of what will happen the following week as they are not able to build up food reserves. In practice, the lesson is that they eat as much as they can since they do not know when they will fall below the food sufficiency line.20,21

Household food insecurity is defined as limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, and limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways.18,22 The possible paradoxical association of hunger and food insecurity with childhood obesity was first raised in a case report in 1995.23 The author speculated that this association may be because of “an adaptive process to food shortages whereby increasing the consumption of inexpensive energy dense foods results in increasing body mass”. Plausible mechanisms that may explain this association include cheaper cost and over-consumption of energy-dense foods, overeating when foods become available, metabolic changes that may permit more efficient use of energy, fear of food restriction, and higher susceptibility to hunger, disinhibition and environmental cues.24,25

Socio-economic disadvantage in childhood is positively associated with an increased risk of obesity in adulthood. Lissau and Sorensen26 showed that 9–10-year-old children in Copenhagen rated as dirty and neglected by school personnel were 9.8 times more likely to be obese 10 years later. Olson et al in 200727 attempted to explain why food insecurity as it is experienced in rich countries such as the USA results in adult obesity. After following 30 rural women with at least one child, their most important conclusion was that growing up in a poor household appeared to “super-motivate some women to actively avoid food insecurity in adulthood by using food to meet emotional needs after deprivation”. As the authors point out, this behaviour towards food may be a possible mechanism for explaining the association between childhood poverty and adult obesity.

Drewnowski, in 2007,28 demonstrated that much of the past epidemiologic research is consistent with a single parsimonious explanation: obesity has been linked repeatedly to consumption of low-cost foods. Refined grains, added sugars, and added fats are inexpensive, tasty and convenient. The fact that energy-dense foods cost less per megajoule than nutrient-dense foods, means that energy-dense diets provide not only cheaper energy, but may be preferentially selected by the lower-income consumer. In other words, the low cost of dietary energy (dollars/megajoule), rather than specific food, beverage, or macronutrient choices, may be an important predictor of weight gain amongst poorer populations.

In examining the childhood obesity epidemic from the perspective of economics, Cawley29 reports that the market has contributed to the recent increase in childhood overweight in three main ways. First, the real price of food fell, particularly energy-dense foods; second, rising wages increased the “opportunity costs” of food preparation for people in the work-force, encouraging them to spend less time preparing meals; and third, technological changes created incentives to use prepackaged food rather than to prepare foods.

Several economic rationales justify government intervention in markets to address these problems. First, because free markets generally under-provide information, governments may intervene to provide consumers with nutrition information they need. Second, because society bears the soaring costs of obesity, the government may intervene to lower the costs to taxpayers. Third, because children are not what economists call “rational consumers”—they cannot evaluate information critically and weigh the future consequences of their actions—the government may step in to help them make better choices. The government could disseminate information to consumers directly, it could protect children from the marketing of unhealthy foods and could also apply taxes and subsidies that discourage the consumption of these or encourage physical activity. It could also require schools to remove vending machines for soft drinks and candy. From the economic perspective, policy-makers should evaluate these options on the basis of cost–effectiveness studies.

Until recently, it was commonly thought that nutrition-related chronic diseases were associated with wealthy societies, but it has been shown in almost all categories of developing countries that nutrition imbalances are most frequent among the poor.30 This is especially evident in migrant populations; for example, in northern Mexico, there has been a dramatic increase in obesity and diabetes among indigenous populations who have become progressively urbanized and have abandoned their traditional diets in favor of a Western pattern of consumption and decreased physical activity with serious consequences for health.31 The availability of foods, income and advertising are the main determinants of the demand for certain foods among the poor, particularly sugary drinks and high fat salty and sweet snacks.28

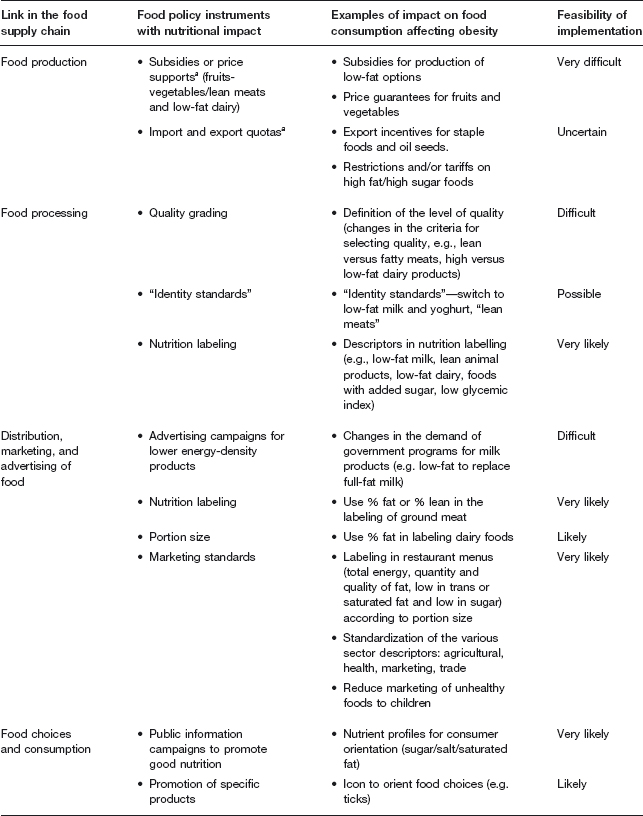

Table 33.1 illustrates policy instruments and activities that can be applied at different stages of the food supply chain to reduce obesity, as well as the feasibility of implementing them. As this table demonstrates, most policy instruments are feasible to implement if the different actors involved (government, food companies, marketers, consumers, the public, scientific community, etc.) place the health of the population as a high priority. These policy options are pertinent to countries in the epidemiological transition as well as to industrialized countries. As shown in the table, we considered that price control and export quotas may be more likely applicable in developing countries since governments play a stronger role in trade policies.

Table 33.1 Potential supply-side and demand-side interventions in the food supply chain to modify food consumption, for example, in this case to reduce obesity.

aThe likelihood of applying these policy instruments is greater in developing countries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree