Summary and recommendations for research and practice

- Well-evaluated community-based obesity prevention programs are needed to provide the evidence of effectiveness of such approaches.

- Selection of priority communities for program implementation should take account of needs (e.g. level of disadvantage) as well as likelihood of success.

- A capacity building approach should underpin implementation of obesity prevention programs.

- Health promotion principles are applied to community engagement, program planning and implementation, and evaluation design, but these are inherently complex and contextual.

- Sustainability must be built in from the start, and means placing a higher priority on policies and capacity building than on events, awareness raising and education.

- Future challenges include securing sufficient investment in programs and evaluations, incorporating socio-cultural aspects, and moving from implementing individual projects to reorienting existing systems towards contributing to the obesity prevention efforts.

Community level action to promote healthy eating and physical activity is a central component of obesity prevention efforts. Ideally, these actions should complement wider state- or national-level action, particularly policy actions needed to make environments less obesogenic. 1 In practice, programs at the community level are being established much more rapidly than policies at a state or national level. At this stage, however, the evidence base for what works and what does not work at a community level is relatively narrow, 2,3 therefore there is an imperative to properly evaluate major programs that are being implemented. 4 Establishing well evaluated demonstration projects is critical for creating the evidence about what works for whom, why, and for “what cost?”

The planning, implementation and evaluation of community intervention programs takes several years. This is especially the case if the programs are large and multi-faceted, if the structures and organizational relationships need to be built from scratch, if the stakeholder groups are numerous or require substantial relationship building, or if the resources and leadership support are low. Sustainability issues are often not high on the agenda in the early stages as people are immersed in community consultations, hiring staff, setting up governance structures, developing action plans, and so forth. However, as the evidence of long-term effectiveness of interventions emerges, the focus of choosing more sustainable action should increase.

Basic health promotion principles for the implementation of any community programs include: the need for community engagement and capacity building; program design and planning, including governance and management structures; implementation and sustainability; and evaluation. This chapter briefly expands on each of these areas, beginning with the selection of communities. Two examples of how community-wide programs are being implemented, one from France (the EPODE program) and in Australia (the Sentinel Site for Obesity Prevention), are then presented.

A community’s context and their existing capacity to find their own solutions to the drivers of obesity will differ enormously between communities. Building the evidence for community-based approaches to obesity prevention is in its early stages in all countries and it is, therefore, important to strike the right balance between targeting communities of highest need versus those with the highest likelihood of success. Box 26.1 highlights the characteristics of communities with a high chance of success, and these could form part of the criteria for selecting communities for community-wide obesity prevention action.

Principles of community engagement and capacity building

The principles of community engagement and capacity building are fundamental to any health promotion process. Participation is essential to sustain efforts, and community members have to be at the centre of health promotion action and the decision-making process for them to be effective. 5 To achieve sustainable outcomes, capacity building processes are required whereby the development of knowledge, skills, commitment, leadership, resources, structures and systems occur. 6–8

Community engagement

The community engagement process for obesity prevention action in communities involves a process much like that which would occur in any health promotion process (Table 26.1). However, “obesity” is such a negative term and there is a real risk of increasing stigmatization, so obesity prevention efforts are usually framed within the community in a different manner, such as the promotion of healthy eating, physical activity and/or healthy weight.

Box 26.1 Characteristics of communities which influence the likely success of obesity prevention programs

- level of support and leadership to provide program champions and access to resources;

- amount of available resources, external and internal, within settings and organizations;

- access to target populations through sufficient settings;

- structures and partnerships of existing organizations which would provide the planning, management and implementation roles;

- ability to be evaluated (funding, access to evaluation team, meeting design criteria, sufficient numbers etc.);

- context of community interventions:

- ownership (research-initiated, service-initiated, community-initiated)

- stage (demonstration project, roll-out)

- size (single/few settings to whole large community)

- origins/aims (obesity prevention, nutrition promotion, community building, non-communicable disease prevention etc.).

The engagement process is critical for ensuring relevant organizations, settings leaders and other key stakeholders become committed to the proposed policies and programs and are able to work collaboratively around a common plan of action. Community members are usually able to provide information on

1. the needs of the community in relation to the issue;

2. the context of their community and key settings;

3. the socio-cultural dimensions; and

4. existing programs, networks and resources to support the project.

Ultimately, the stakeholders need to inform the action plan and are members of governance and management structures aligned to the implementation efforts. Establishing working coalitions and successful collaborations, with a lead agency taking the initiative and driving implementation from the grass roots, are fundamental to providing empowerment and sustainability. 8–10

This development of partnerships and inter-sectoral collaborations need to be recognized as formal relationships between different sectors or groups in the community. They are usually more effective, efficient and sustainable in achieving intended outcomes than are organizations working alone. 7 Community ownership comes about by engaging and committing to the process and the outcomes, working collaboratively to develop a plan of action and then taking the responsibility to implement it.

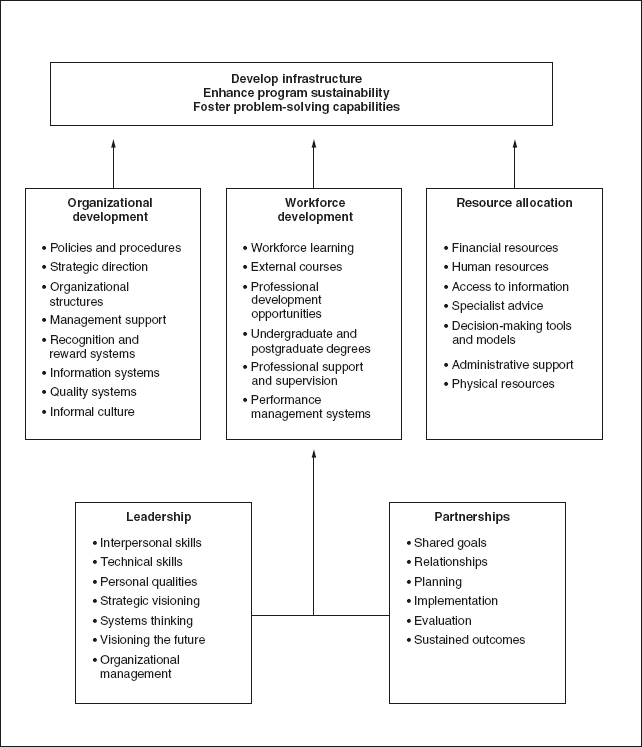

Capacity building

Capacity building processes are usually required from the outset to build the knowledge, skills, commitment, leadership, resources, structures and systems to initiate and sustain implementation efforts. Figure 26.1 provides one such framework, which can be applied to obesity prevention efforts. The intent of capacity building needs to be clear from the beginning. Usually, it is best employed systematically,to build the capacity of the community to develop infrastructure, enhance program sustainability or build capabilities of community members.11 Integrating such a framework into the action plan can assist in desired outcomes.

Principles of program design and planning

Program design

Program design begins with an assessment of contributing factors in the context of the community. Decisions can then be made about the focus and size of program, as well as about the barriers and facilitators to action.12 The Analysis Grids of Elements Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) framework and process was specifically designed for obesity prevention, and is a useful tool for assessing a community’s environment and for prioritizing information from the community to guide action.13,14 The overall approach needs to be framed to support the community’s view of the problem in order to minimize harm, stigmatization and blame.15

Program planning

Using a strategic plan for the program planning process can assist in attaining a balanced resource investment. The portfolio of interventions in the strategic (action) plan stems from the problem and contextual analysis of the community and should complement national, state and regional policies and plans. Essentially, the action plan guides implementation whereby objectives and strategies to achieve a stated goal are recorded, with accountability and timeframes assigned. The action plan needs to consider and build on the strengths of existing activities and partnerships in the community and use a mix of evidence-based and innovative approaches.16 Active change processes (theories of change) need to underpin the action plan to influence environments (settings), organizations, policies and individuals.

The use of program logic models can assist all key stakeholders to understand the components and outcomes to the planned program. The path between goals, objectives and strategies are defined and the fundamentals of the program design can be checked and deemed logical.17

Governance and management structures

Good program management is required to implement the action plan. Governance structures and lines of accountability are essential. A structured approach to project management ensures accountability, progress and quality, and implements risk management and problem-solving strategies among project staff and key stakeholders. Partnership and organizational relationships, and lines of communication need to be specified. Progress reports/updates to funding bodies and key stakeholders are also important communication tools.

Principles of implementation and sustainability

Sustainability needs to be built into the action plan from the outset. The natural tendency for actions to be dominated by awareness-raising activities, one-off events, and educational strategies needs to be countered by a conscious effort to implement the more sustainable strategies of capacity building strategies (above), creating supportive policies, environments and social norms. Attention to the quality of implementation is also critical.

Policies and environmental change

Policies are the “set of rules” that influence the environments, which in turn influence behaviors.1 Settings-based food service policies are a good example. School food policies that take junk food out of the school canteens, or a workplace cafeteria policy that makes low-fat milk the default choice (i.e. automatic option unless otherwise specified) for coffee, not only make the healthy choices easier but also signal what those healthy choices are. The policy influences the behavior indirectly by influencing obesogenic environments and sending health behavior signals. This is in contrast to seat belt or smoking policies and laws which directly mandate behaviors.

Social change

Social marketing is the application of marketing concepts, tools and techniques to any social issue.18 Social marketing not only targets individual behavior change, but also attempts to bring about changes in the social and structural factors that impinge on an individual and their opportunities, capacities and right to a healthy and fulfilling life. The emphasis of social marketing should target community leaders who have the power and influence to make major institutional policy and legislative changes rather than focusing on voluntary health behaviors to individuals in the general population. Changing cultural norms is often difficult and controversial, but norms have powerful, sustainable effects on behaviors. Using social marketing for obesity prevention requires an integrated approach in the project’s action plan and communication plan. The testing of approaches, resources, messages and images with or for the target group is imperative to ensure appropriateness, acceptability and comprehensibility.

Quality of implementation

Because little has been published on the implementation of obesity prevention efforts or the extent of effort required for change, principles for optimal implementation are still being developed. The use of process evaluation, to assess fidelity, completeness, exposure, satisfaction and reach of intervention activities, provides a good monitoring system.19 The review and adjustment of implementation can then be achieved. Implementation efforts also need to build the capacity of all key stakeholders to ensure actions/activities are ongoing and sustained.

Responding to opportunities, often unexpected ones (e.g. emerging community requests, linking with new programs or partners) can assist with sustainability. This is especially the case where initiatives are integrated into other systems and structures and build on other areas of the community’s capacity.6

Evaluation is covered in Chapter 19 in detail, but some principles as they apply to the planning stages are outlined here. It is very important that the approach and framework for evaluation are developed concurrently in the program planning phase. 12 The capacity to conduct the evaluation needs to match the size and scope of the evaluation intended. The framework or evaluation plan should contain options for measuring process, impact and outcomes of the implementation. Outcome and impact evaluation correspond to changes in the program’s aims and objectives. For well-evaluated demonstration projects, these would include changes in anthropometry, behaviors (skills, knowledge), environments and capacity.4 Ideally, an economic evaluation should be conducted to contribute to the evidence of cost–effectiveness and optimal implementation. The use of standard measures and tools will enable a com parison with other programs/projects. Documenting lessons learnt is valuable in dissemination and can contribute to the evidence of what does, or does not, work. The context for evaluation needs consideration as current organizational, policy, and community contextual factors can have a major impact on the outcomes.

Evaluation findings need to be disseminated within the community in the first instance and this should occur as the findings become available so that knowledge transfer can be applied back in the community. At the next level, translation of evidence from research into policy and practice is required for a continuous response to obesity at the public health policy level.

Key challenges in establishing and sustaining community interventions

The very nature of community-based interventions creates challenges because they are inevitably complex to implement and evaluate, they are always contextual, and are usually poorly resourced. However, a few particular challenges in existing and future community approaches to obesity prevention warrant special mention.

Sufficient investment in programs and evaluations

The time lag from the early signs of the obesity epidemic in the early 1980s to the first phase of community-based demonstration projects in a few countries in the mid-2000s was substantial and, even now, the funding investment to build the evidence base for effectiveness has remained very low. Government-funded programs traditionally provide little funding for evaluation (which may cost as much as the program itself if effectiveness and cost–effectiveness are to be measured) and research-funded programs tend to pay little attention to program sustainability and integration into existing services.

Complexity of program implementation and evaluation

There are many different approaches to program implementation but they all encounter the complexity of having to juggle multiple partners, agendas, funding constraints, and personal and organizational relationships. There is no simple formula for negotiating this complexity and the mix will be different for each context. Similarly, the evaluation of multi-sector intervention programs which are under community control are complex, especially when potential comparison populations are exposed to a variety of other local, state and national programs to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Quasi-experimental designs can be used for program evaluation but they all carry higher risks of arriving at false negative or false positive conclusions than the more rigorous controlled trials that randomize individuals or clusters (e.g. schools).

Incorporating socio-cultural components

There are significant differences in obesity prevalence rates across ethnic groups and this indicates that socio-cultural factors must be considered in any implementation program in those groups. 20,21 For example, if the over-provision and over-consumption of food is a fundamental expression of the underlying cultural values of showing care, respect and love between people, how can obesity prevention programs and messages be framed to reorient those obesogenic manifestations of positive cultural values? This is a challenge that few programs have embarked upon to date.

Moving from projects to systems

Demonstration projects have an important role to play in creating the evidence and experience about what works for whom, why, and for what cost. In the coming years, the findings, both positive and negative, will emerge from the community-based projects around the world. The next phase is not to establish more projects but to take these lessons and systematically incorporate them into the existing systems operating in schools, primary care, local government and the communities. Implementation research will be needed to work out how to ensure that existing knowledge and best practice gets converted into these systems. This knowledge exchange research and systems science are relatively new in health promotion but will need to be rapidly applied if the emerging evidence is to be converted into action.

Case study 1 the EPODE program, France

Introduction

Ensemble Prévenons l’ Obésité Des Enfants (EPODE —Together, let’s prevent childhood obesity) is a childhood obesity prevention community-based intervention, which was established in France in 2004. Its principles are to work with local stakeholders to influence the behavior of the whole family and to change the family’s daily environments and social norms in a sustainable manner, thus contributing to the stabilization then decrease in overweight and obesity prevalence in children.

The concept was successfully piloted in the Fleurbaix Laventie Ville Santé Study (FLVS) from 1992 to 2007.22 FLVS is now part of the EPODE program along about 200 towns across France. The program is also being adopted and implemented in Belgium, Spain, Greece, Australia and Canada.

Structure and implementation

A National Coordination team, supported by a scientific advisory board, strong political will, and public-private funding partnerships make up the four pillars to EPODE. The FLVS non-governmental organization, which initiated the FLVS Study, is fundamental to EPODE because it receives the funding from public and private partners (about 50:50) and contracts the coordination to a professional communication company (PROTEINES ®). The National Coordination/Social Marketing Team at PROTEINES ® is the hub of EPODE with specialties in project management, training, social marketing, communication and public relations. It also organizes sustainable funding. Its primary role is to support the implementation of the EPODE program in local communities, towns, cities, developed to meet contextual needs (cultural, sociological, economic and political). As a resource centre, it provides all social marketing materials, tools (including a methodology book for progressive implementation), guidelines, quarterly roadmaps and a dedicated toolbox to engage key stakeholders and professional development/training to the local community. The roadmaps utilize group dynamics, decision-making processes and social policy modification to foster sustainable change in educational schemes for nutrition and physical activity. The National Coordination is advised by a scientific committee of independent experts in education, psychology, sociology, exercise and nutrition sciences.

City mayors are the point of entry into a community. In France, councils have jurisdiction over kindergartens and primary schools (core target population). The mayors are required to submit an application to be an EPODE community, to dedicate a full-time project manager and to commit at least √1 per capita for the interventions each year for five years (many commit more). The mayors act as champions for EPODE and sign a charter outlining the involvement of the city and committing to some rules.

The mayor appoints a project manager to implement EPODE using the tools provided by the National Coordination team. Their role is to establish networks, coordinate a local multi-disciplinary steering committee, and disseminate the specific tools, road-maps and briefings to professional groups willing to be involved in the operational process.

To succeed in establishing committed local stake-holders, the project managers and their teams undertake four fundamental steps:

1. raising awareness of the obesity issue and its solutions (without stigmatization), and recruiting a large number of stakeholders/key opinion leaders (public, private) to participate on a voluntary basis;

2. training stakeholders to convey positive messages and creative solutions guided by international recommendations, behavioral change theory, and the experience of trained local experts;

3. implementing actions in schools and towns, using the developed tools and methodologies, guided by local initiatives in keeping with EPODE’s philosophy with materials being validated by the national scientific committee.

4. assessing effectiveness by measuring children’s BMI, the level of stakeholders ’ involvement and the quality of spontaneous actions undertaken.

Financing comes from public-private partnerships, established at the national and local level. Representatives from private business (e.g. food industry, insurance sector), academia, and local and national politicians are brought together. The private support is strictly financial and they sign an ethical charter confirming their intention (supporting a public health prevention project, independent of their own agendas).

Evaluation

All EPODE communities measure and weigh children annually at school and because participation is considered the norm, the response rates are 90–95%. The data are then a virtual census and statistical tests are not required to give confidence about what is occurring in participating communities. There are no comparison populations being measured and it is, therefore, difficult to assess the impact of the program compared to having no program. The costs of obtaining comparative data and the difficulty of evaluating the influences of a multi-factorial intervention on complex behaviors are major evaluation challenges.

The monitoring of actions is an important part of evaluation. Since its launch in 2004, there have been more than 1,000 actions per year by local stakeholders in the first ten EPODE towns. A detailed monitoring chart of these actions, filled by the project managers, enables a continuous process evaluation. Economic, media and sociological aspects are also evaluated.

Sustainability

A number of factors contribute to sustainability of the project. The strong philosophy of ensuring that no stigmatization occurs ensures that perceived risks are minimized. The structure of EPODE maximizes sustainability by ensuring leadership and commitment (mayors signing on), the ongoing funding (private: public, national: local), the program quality (consistency across all towns/cities through the National Coordination team), and the local relevance and engagement (local project manager and steering committee) are built into the design and processes.

The local stakeholders develop new skills and create strong partnerships and social ties in their work. This means that they feel valued and know they are part of a large positive program for the community. Families live in an “ecological niche” (village/town, neighborhood) where events of daily life occur (education, work, shopping, medical care, leisure transport, etc.). Local stakeholders can have a strong influence in these settings, supporting families and disseminating common messages. EPODE involves the whole community creating mobilization of local resources.

Since 2000, France has had a national strategy to promote healthy lifestyles and implement supportive policies such as restricting food advertising practices. This has created a positive national context, which has facilitated the implementation of EPODE.

Transferability

The initial ten EPODE towns have created a mayors ’ club to promote the concept among other local authorities, explore financial, physical and human resources, extend the network to foster operational partnerships, and develop political awareness around childhood obesity. Implementation is successful from small towns (80 inhabitants) to large cities (Paris, beginning in four districts). EPODE cuts across political differences and socio-economic status. The model has also been adopted and adapted in countries outside France. Further details can be found on: www.epode.fr.

Case study 2 Sentinel site for obesity prevention, Victoria, Australia

Introduction

The Sentinel Site for Obesity Prevention established three whole-of-community demonstration projects located in the Barwon-South Western region of Victoria, Australia. The projects were based on health promotion principles taking a community capacity building approach 23–25 and aimed to build actions, community skills and contribute to the evidence for obesity prevention.

Each project aimed to strengthen their community’s capacity to promote healthy eating and physical activity, and to prevent unhealthy weight gain in children.26 All action plans had three objectives around community capacity building, communications and evaluation, with a further 4–6 behavioral objectives and 1–2 innovative or pilot project objectives. All projects used quasi-experimental evaluation designs with parallel comparison groups and >1,000 children in each arm. 26 Funding came from multiple government and public research funding sources.

Sentinel site projects

“Romp & Chomp” targeted preschool children and their families within the City of Greater Geelong from 2005 to 2008 (~12,000 children under 5 years of age). Nineteen long day care facilities, 44 family day care centers and 38 kindergartens consented to being involved in the evaluation of the project. The project had a strong focus on developing sustainable changes in areas of policy, socio-cultural, physical and economic environments.27

“Be Active Eat Well” (BAEW) targeted children aged 4–12 years and their families in the rural town of Colac. Primary schools (n = 6) were the major setting for action but other settings such as kindergartens, neighborhoods and fast-food outlets were involved.28 Positive anthropometric changes have been reported in this project.29

“It’s your Move!” focused on secondary school students aged 13–17 years. All secondary schools (n = 5) from the East Geelong/Bellarine Peninsula area of Geelong were selected. Student ambassadors worked throughout the project as advocates and implementers. This project was part of the four-country Pacific intervention study: Obesity Prevention In Communities (OPIC). 30,31

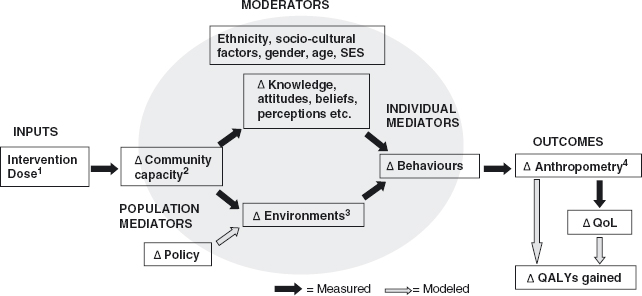

A research team for the Sentinel Site, based at Deakin University, supported the interventions, provided training, assisted with building capacity and, in particular, was responsible for the evaluation component of each project. The full logic model for the way the interventions were assumed to influence the outcomes and their associated measured and modeled components is shown in Figure 26.2.

Community engagement and establishing structures and roles

The projects began by engaging key stakeholders in the target settings and relevant government and non-government agencies. Champions (people visible and influential in the community) helped cement the engagement process.

Program management, organizational structures, coordination and strategic alliances were established to support implementation. An interim steering committee with membership from stakeholders established the project and employed a project coordinator. After 6–9 months this committee was structured into a two-tiered management system (Reference Committee and Local Steering Committee) to coincide with the implementation phase. The Reference Committee’s role was to provide higher-level strategic input and support and the Local Steering Committee was empowered to implement the project, including budgetary decisions. Members included project staff and those at the grass roots in the project’s key settings and terms of reference were established for each committee.

Developing an action plan

The ANGELO process was used to assist each community set priorities for action, culminating in an action plan.14 This was achieved mainly through a facilitated workshop with key stakeholders and, in the case of It’s Your Move!, with members of the target group (adolescents). The “elements” in the framework refer to a list of potential target behaviors, knowledge and skill gaps, and environmental barriers developed from the literature, local evidence and experience, and specific analyses or targeted research. 32,33

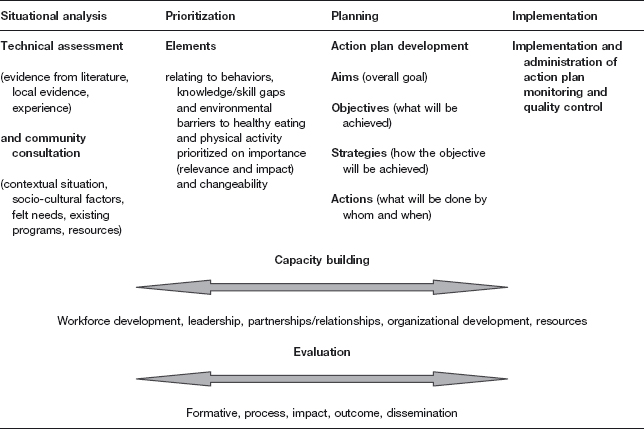

The ANGELO process had five stages as outlined in Figure 26.3, with steps 2–5 occurring within a two-day workshop.14

At the workshop, the situational analysis (stage 1) was presented including evidence from the literature on obesity and obesity prevention and other technical assessments, as well as information from the community engagement process (e.g. existing programs). A potential list of elements were scanned/altered by participants for appropriateness (stage 2) then priori-tized according to importance and changeability (stage 3). Within settings relevant to the community (e.g. homes, early child care settings, schools, neighborhoods), environmental barriers were prioritized. A scoring and ranking process determined priorities. The merge (stage 4) integrated the highest five to seven ranked behavioral, knowledge, skill and environmental elements as targets for action. These were discussed, and in the final step, the agreed priority elements were molded into a structured action plan (stage 5). The behaviors were generally used to create the objectives with the associated knowledge gaps and environmental barriers being used to identify strategies. It was important that objectives were written in Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound (SMART) format.34 The action plans were further refined with the community and timelines, processes and accountability added. The action plan became a “living” document, which guided implementation and evolved through several versions during the life of the project.

Figure 26.2 General logic model for the three demonstration projects of the Sentinel Site for Obesity Prevention.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree