Each of the slices of cheese represents barriers which would, under ideal circumstances, prevent A leading to B. However, all checks and balances can fail at some stage. This is represented by the holes in the slices. For A to be followed by B, the holes need to line up through all the intervening slices. Simplistically viewed, the more checks that are put in place, the less likely an error is to occur. However, the increasing complexity of processes can be counterproductive as humans will avoid or modify one of more of the steps to make life easier.

Consider the following critical incident.

- The wrong dose of a drug has been administered to a patient by a clinician. Why? We know that the clinician should have checked the details of the prescription and confirmed the calculations to ensure that this all matched up with the formulation and strength of the medications to be administered. People do not deliberately make errors and therefore it is not unreasonable to conclude that the clinician thought they had checked and matched everything as described.

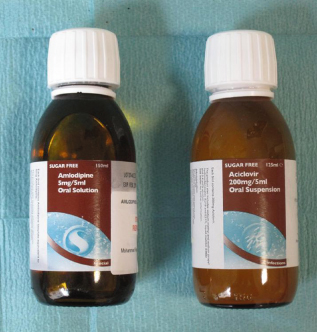

- So why did the error occur? Further information shows that two drugs had been replaced in one another’s normal positions in the ward trolley. The packaging of both was very similar (Figure 25.2).

Ideally, the clinician should have read all of the relevant text on the packaging. However familiar tasks can lead to complacency and subsequent inattention to detail. The clinician picked the medication from its usual place, thought they recognised the box and therefore did not actively review the name and concentration of the drug. Habit can blind us to what we are doing.

In the working environment we may be present at the right time to observe the breaching of a barrier that would normally prevent errors occurring. It is critical that we are vigilant for these breaches and draw the attention of our colleagues to them in order to prevent the progress and completion of an error chain. By convention, events or conditions that might be seen to be on the facilitative path to a critical incident are referred to as red flags. This approach is extremely useful. The more red flags that arise, the greater the risk of an adverse incident occurring and therefore the greater the need to alert the team to stop, review and if necessary resolve the situation.

25.4 COMMUNICATION

Problems with communication underpin a significant proportion of reported critical events. The fact that it is vital that clinicians communicate efficiently and unambiguously in their everyday clinical practice is undeniable. However, what steps do we take to ensure this happens?

When the speaker and listener do not share the same language, the communication issues are obvious and normal practice would be to look to using an interpreter to facilitate dialogue. Many recognise the limitations of discussions carried out through a third party. Even when all parties are using their native tongue, non-verbal signals carry a significant amount of information and meaning, in addition to the words themselves. With these facts in mind it is not difficult to understand why miscommunication is commonplace. This is particularly true in cross-cultural communications where both verbal and non-verbal elements can be completely misinterpreted by both parties.

Studies have shown that we understand around 61% of verbal communication and over 50% of written communication, with the remaining percentages being miscommunicated, misinterpreted or simply misunderstood (Beaty, 1995). The reason for this breakdown in communication is multifaceted and includes our use of non-verbal communication (outside the actual words we use), which has been shown to contribute up to 93% of what we understand (Barbour, 1976). Barbour’s study identified that 38% of communication relates to how words are said (volume, pitch, rhythm, etc.) and 55% to body language (facial expressions, posture, etc.).

These observations are largely based on work from the 1960s exploring the nature of therapeutic counselling conversations. Emerging data show this to be an oversimplification of that which occurs in clinical communications. However, the message remains the same – words spoken or written by one person, with an intent to convey a particular message, may be interpreted entirely differently by the listener or reader. This in itself provides a direct insight into why in a busy clinical environment within which multiple tasks are being undertaken, and without direct visual connections between all team members, miscommunication occurs so frequently. The process of communication can be described as three separate phases:

The resulting outcome in a noisy, highly pressured clinical arena is unsurprisingly one of poor information exchange. Multiple studies, including the document ‘Why mothers die, the confidential inquiry into maternal deaths’ (Lewis, 2007), have reached the same conclusion: poor and ineffective communication is central to clinical error.

The ‘feedback loop’ is an easily implemented technique that can be used to improve communication. It is a process within which the receiver repeats the message back to the sender to acknowledge and clarify that it has been correctly deciphered. It is quick and simple, easy to implement and shows an immediate benefit in busy clinical areas where requests and instructions are being passed on at breakneck speed.

In summary, the discussion above only begins to touch on the complexity of human communication. Beyond this there are many layers of subtlety in our interactions. To try and mitigate the risk of miscommunication, it is vital that both talkers and listeners actively engage in the process.

Teamwork

Teamwork is the cooperative effort of a team of people who have a shared goal and who have a leader with a defined role and the same goal. Good teamwork requires good relationships between team players, who are supportive of each other and can recognise problems amongst individuals within the team.

Body Language and Hierarchy

All parties should always be aware of their non-verbal signals. Those that say ‘I’m bored’, ‘I’m tired’ or ‘I don’t value you’ can all result in one person failing to pass on a key piece of information to another. The presence of a steep hierarchy can be particularly inhibitive as it embeds an attitude into the working culture where staff do not value one another’s input. A culture where junior staff do not feel empowered to speak directly to senior staff, or senior staff are dismissive about concerns raised by junior staff, is inherently unsafe. If a clinical assistant walks into theatre and sees an expanding pool of blood under the operating table, they should feel able to raise their concerns. Whether or not it proves to be clinically important, their input should be positively acknowledged, as next time they might be the first to identify a critical issue.

Speaking Up

| Stage | Level of concern |

| P robe | I think you need to know what is happening |

| A lert | I think something bad might happen |

| C hallenge | I know something bad will happen |

| E mergency | I will not let it happen |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree