Summary and recommendations for research and practice

- Knowledge translation and exchange (KTE) processes are intended to facilitate the creation and application of knowledge.

- To best support obesity prevention knowledge translation and exchange processes need to involve governments, communities (including children and their parents), practitioners and researchers who are holders of implicit and explicit knowledge.

- Tools and strategies are available to support the many purposes of KTE.

- Reflection on the application of KTE tools and strategies is necessary, in order to build the research evidence in this area and to support evidence-informed approaches to obesity prevention.

As discussed in previous chapters, the need for an evidence-informed approach to obesity prevention is challenging but essential. Using research evidence in decision-making processes is often termed “evidence-based practice”, stemming from the principles of evidence-based medicine (EBM). EBM typically involves the “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients”.1 In more recent times, and in domains such as public health where research evidence is more complex, the term “evidence-informed” has been favoured.2 Evidence-informed decisions should be “better matched to the context of application, more efficiently implemented, and more widely acceptable.”3 While EBM has an implied emphasis on research evidence forming the basis of decision making, “evidence-informed” decision making more clearly acknowledges that public health decisions are often informed by research evidence in combination with a range of alternative sources and influences.4

Obesity prevention is likely to be best supported with the use of multi-sectoral approaches across multiple disciplines. The challenge for obesity prevention is that interventions are facilitated through policies at the national, state/provincial, regional and local level. This necessarily involves the generation and synthesis of existing research evidence in combination with practitioner expertise, policy imperatives and community experiences. Given the number of key stake-holders involved in this trajectory between knowledge generation, synthesis and use, “knowledge translation and exchange” has become particularly important. The process of knowledge translation and exchange is thus, extremely complex. Initially it was believed that evidence-informed decision making could be achieved through the simple diffusion of information (e.g. development and dissemination of research reports). However, it is now acknowledged that, at a minimum, knowledge translation and exchange (KTE) must involve the building and maintenance of collaborative relationships between and among key stakeholders and researchers.5,6

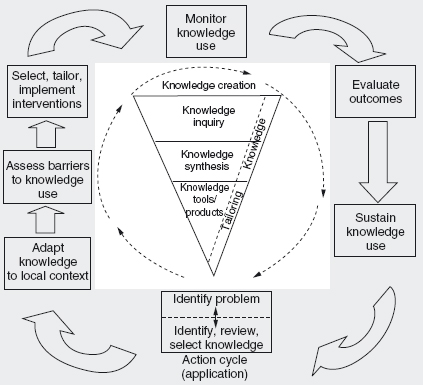

In a more traditional sense, knowledge translation (KT) has been defined as the “exchange, synthesis and ethically sound application of research findings within a complex set of interactions among researchers and knowledge users”.7 The processes and types of knowledge used in more contemporary KTE processes refer not only to research findings or research evidence.8 Knowledge can be viewed as either explicit or tacit. Explicit knowledge is information that can be explained in words or symbols and is often written down.9 It can, therefore, be easily shared or copied (e.g., a program evaluation that is published in a peer-reviewed journal). Tacit knowledge is generated through experience. It is, therefore, difficult to share without some level of interpersonal contact (e.g., sharing professional expertise in identifying options for working with refugee families to promote healthy eating).9 In obesity prevention, decision making requires the careful consideration of a number of forms of knowledge, which can be viewed as either tacit or explicit including theory, intervention research, community views, local context, policy evaluation and expert opinion. This process occurs in the “action cycle” outlined in Figure 22.1.

This chapter explores how to use research evidence within a KTE framework that considers different types of knowledge to address obesity prevention.

The characteristics of KTE needed to support obesity prevention

Interaction

It appears that an essential component of KTE is interaction between various constituents.11,12 This may involve researchers, decision makers, policy-makers, practitioners and communities. The communication of knowledge can be operationalized using a number of mechanisms, including websites, knowledge brokers, tailored or targeted messages, email, health messages, networks and formal and informal meetings.11,13

Multi-sectoral approach

As discussed widely in the evidence sections of this book, to be effective, action to address obesity needs to take a multi-sectoral approach. KTE processes must, therefore, acknowledge the influences (e.g. political, historical), types of knowledge and accountability requirements operating within each relevant sector. For example, some sectors may rely more heavily on types of knowledge (e.g., modeling is used within the transport sector) unfamiliar to individuals working in the health sector.14

The key to working across multiple sectors is communication and engagement. Part of the challenge is that those working outside the health sector may not view their work as health-related or relevant to obesity prevention. Exposure to new ideas (particular related to the determinants of health), concepts of evidence and different ways of working are essential to supporting evidence-informed decision making for obesity prevention. Those working in the health sector may begin to build these relationships by involving key partners (e.g., schools, early childhood services, transport, food supply) in health-related decision making. Other strategies may include offering to share advice in the development of policy related to the determinants of obesity prevention, sharing key publications with key contacts, summarizing research evidence likely to be of relevance or interest to these partners, and building formal networks with interested parties to support evidence synthesis and generation. It goes without saying that nurturing these relationships takes time and commitment.

Understanding context

Context refers to the “social, political and/or organizational setting in which an intervention was evaluated, or in which it is to be evaluated”.15 It must also capture the characteristics of those living and working within these settings (e.g., demographics). Understanding the context in which knowledge was originally created is as important as understanding the context where knowledge will ultimately be applied.15,16 For example, if you were planning the implementation of a school-based intervention, it would be important to understand why a particular school-based intervention worked in rural New Zealand as well as considering whether it could be applied in metropolitan Sydney.

Planning for and implementing KTE strategies is complex with many barriers and challenges to be overcome. A significant issue concerns the engagement of multiple stakeholders in the KTE process, each of whom brings their unique values, perspectives and attitudes with respect to evidence-informed decision making. The challenge lies in allowing for these differences to be part of the process while promoting an environment where a common goal is sought and is achievable. Additional barriers include absence of personal contact between researchers, policy-makers and practitioners, lack of timeliness of research, mutual mistrust, power and budget struggles, poor quality of research, research that does not answer questions relevant to decision makers, political instability and debates about what constitutes evidence.17–19 A number of models/frameworks have been developed to summarize and support these complex processes.6,16,20

Of particular relevance to obesity prevention is the framework developed by the Prevention Group of the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) to support the translation of research evidence into action.20 This framework is practically oriented and identifies processes to be undertaken in five key stages:

1. building a case for action;

2. identifying contributory factors and points of intervention;

3. defining opportunities for action;

4. evaluating potential interventions; and

5. selecting a portfolio of specific policies, programs and actions.

Each stage is cumulative and culminates in the development of a plan to support the combination of research evidence, theoretical perspectives and contextual factors into a plan for translation into action.20 It promotes KTE by encouraging those who use it to look not only at the research evidence but to explore the views and perspectives of decision makers and communities, to consider innovative approaches and to think outside the traditional health sector settings.

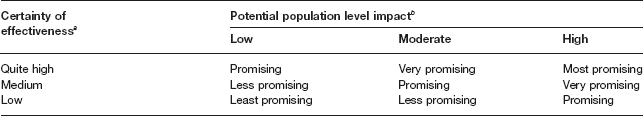

In acknowledging that there is limited research evidence to address obesity, the IOTF has suggested the development of a “promise table” as a way of helping to evaluate potential interventions.20 It supports the consideration of interventions at varying levels of certainty of effectiveness by mapping against potential population impact (see Table 22.1). In doing so, it allows decision makers to consider interventions with high levels of potential population impact where the certainty of effectiveness may be less clear.20

Table 22.1 Mapping the research evidence: a “promise” table.20

aThe certainty of effectiveness is judged by the quality of the evidence, the strength of the program logic, and the sensitivity and uncertainty parameters in the modeling of the population impact.

bPotential population impact takes into account efficacy (impact under ideal conditions), reach and uptake, and it can be measured in a number of ways such as effectiveness, cost–effectiveness, or cost–utility.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree