Normal cerebral blood flow is 50 mL of blood per 100 g of brain tissue per minute. A fall in cerebral perfusion pressure decreases cerebral blood flow. A flow below 20 mL/100 g brain tissue/min will produce ischaemia. This in turn increases cerebral oedema, causing a further rise in ICP. A cerebral blood flow below 10 mL/100 g brain tissue/min leads to electrical dysfunction of the neurones and loss of intracellular homeostasis.

A generalised increase of ICP in the supratentorial compartment initially causes transtentorial (uncal) herniation, leading to transforaminal (central) herniation and death. In uncal herniation, the third nerve is nipped against the free border of the tentorium, causing ipsilateral pupillary dilatation secondary to loss of parasympathetic constrictor tone to the ciliary muscles. In central herniation, also known as coning, the cerebellar tonsils are forced through the foramen magnum.

In childhood, the most common cause of raised ICP following head injury is cerebral oedema. Children are especially prone to this problem. They may, of course, also have expanding extradural, subdural or intracerebral haematomas that require prompt surgical treatment.

Depending on the aetiology of the raised ICP, treatment is either aimed at preventing it rising further or at removing its cause (by surgical evacuation of haematomas).

There are special considerations in infants with head injuries. Unfused sutures allow the cranial volume to increase initially. Large extradural or subdural bleeds may occur before neurological signs or symptoms develop. Such infants may show a significant fall in haemoglobin concentration. In addition, the infant’s vascular scalp may bleed profusely, causing shock. In children aged over 1 year with shock associated with head injury, serious extracranial injury should be sought as the cause of the shock.

16.2 TRIAGE

Head injuries vary from the trivial to the fatal. Triage is necessary in order to give more seriously injured patients a higher priority. Factors indicating a potentially serious injury are shown in the box below.

- History of substantial trauma such as involvement in a road traffic accident or a fall from a height

- A history of loss of consciousness

- Children who are not fully conscious and responsive

- Any child with obvious neurological signs/symptoms such as headache, convulsions or limb weakness

- Evidence of penetrating injury

16.3 PRIMARY SURVEY

The first priority is to assess and stabilise the airway, breathing and circulation as discussed in Chapter 13. Head injury may be associated with cervical spine injury, and neck immobilisation must be achieved as previously described.

Pupil size and reactivity should be examined and a rapid assessment of conscious level should be made. In the first place, the AVPU classification may be used.

In a time-limited situation, it is not essential to work out the numerical Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score immediately, although the EMV (eye, motor, verbal) responses will have been noted. But it is important to note the response to voice, or pain (if not responding to voice), in more detail using the GCS before proceeding with neurological resuscitation. The assessment serves as a baseline for continuing care and as a key indicator of the need to intervene immediately.

16.4 RESUSCITATION

Immediate control of the airway, breathing and circulation should be carried out in response to the primary survey findings, according to the general approach in Chapter 13. This support will help to prevent secondary cerebral damage caused by hypoxia and shock arising from both the head injury and other coexistent injuries.

During the primary survey assessment of disability, any evidence of decompensating head injury will have been recognised. In the severely injured child, extra information from blood gas sampling will be obtained during the resuscitation phase or from ongoing monitoring. On the basis of simple clinical evaluation, supported when necessary by blood gas data, a set of indications for immediate intubation and ventilation in severe head injury have been recommended (in the UK, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has produced evidence-based guidelines for treatment, imaging and referral).

- Coma: not obeying commands, not speaking, not eye opening (equivalent to a GCS score of < 8)

- Loss of protective laryngeal reflexes

- Ventilatory insufficiency as judged by blood gases: hypoxaemia (PaO2 < 65 mmHg (9 kPa) on air or <100 mmHg (13 kPa) with supplimental oxygen) or hypercarbia (PaCO2 > 45 mmHg (6 kPa))

- Respiratory irregularity

16.5 SECONDARY SURVEY AND LOOKING FOR KEY FEATURES

History

The history of the injury itself and the child’s course since the injury should be established from bystanders and pre-hospital personnel. Other history should be obtained from parents or carers.

Examination

The head should be carefully observed and palpated for bruises and lacerations to the scalp and for evidence of a depressed skull fracture. Look for evidence of a basal skull fracture, such as blood or CSF from the nose or ear, haemotympanum, panda eyes or Battle sign (bruising behind the ear over the mastoid process).

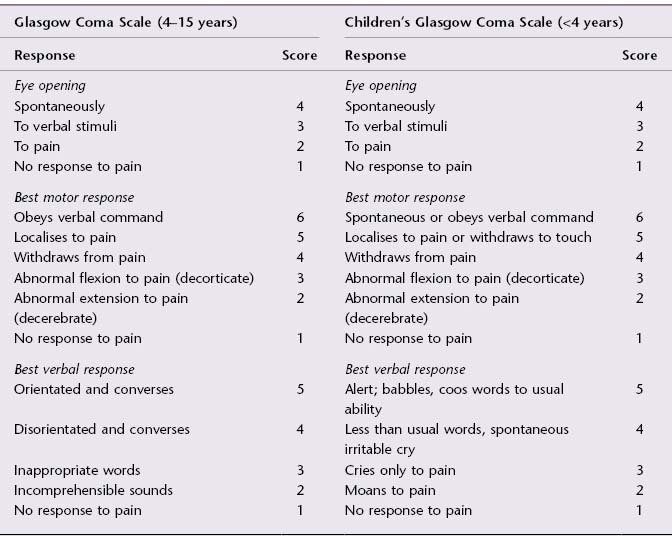

The conscious level should be reassessed using the modified Glasgow Coma Scale if the child is less than 4 years old, or the standard scale in older children. These scales are shown in Table 16.1. Coma scales reflect the degree of brain dysfunction at the time of the examination. Assessment should be repeated frequently – every few minutes if the level is changing. Communication with the child’s caregivers is required to establish the child’s best usual verbal response. A ‘grimace’ alternative to verbal responses should be used in pre-verbal or intubated patients (Table 16.2).

Table 16.1 Glasgow Coma Scale and Children’s Glasgow Coma Scale.

Table 16.2 The best grimace response.

| Grimace response | Score |

| Spontaneous normal facial/oromotor activity | 5 |

| Less than usual spontaneous ability or only response to touch stimuli | 4 |

| Vigorous grimace to pain | 3 |

| Mild grimace to pain | 2 |

| No response to pain | 1 |

The pupils should be re-examined for size and reactivity. A dilated, non-reactive pupil indicates third nerve dysfunction due to an ipsilateral intracranial haematoma until proven otherwise.

The fundi should be examined using an ophthalmoscope. Papilloedema will not be seen in acute raised intracranial pressure, but the presence of retinal haemorrhage may indicate non-accidental injury in a young infant.

Motor function should be assessed. This includes examination of extraocular muscle function and facial and limb movements. Limb tone, movement and reflexes should be assessed and any focal or lateralising signs noted.

Investigations

Blood Tests

Blood for full blood count, clotting, glucose, urea and electrolytes should already have been taken during the immediate care phase. Blood for cross-matching should have been sent off at the same time. Arterial blood gases should be taken in head-injured children to allow careful control of PaCO2 and PaO2, as well as to check pH and base excess or lactate.

Imaging

Plain radiographs of the chest and pelvis may have been taken during the primary survey and resuscitation phase, depending on the mechanism of injury and the current state of the child. If not, reconsider the need for them at this stage. The chest film will need to be repeated if the child is subsequently intubated.

In severe head injury, a CT scan is indicated. In non-accidental injury and in some cases of penetrating head trauma, plain skull films still have a useful role. For other head injuries, this once common investigation has been supplanted by CT scanning, on the basis of evidence in the literature. Indications for performing an urgent head CT scan are summarised below (UK NICE guidelines).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree