Summary and recommendations for practice

- Marketing has a powerful influence on all our behaviors.

º It comprises consumer orientation, multi-faceted working and strategic planning.

º When harnessed to energy dense foods it has contributed to the obesity pandemic.

º It can also be a force for good in the form of social marketing.

- Experience from tobacco control suggests how this potential can be realized.

- The ultimate need is to significantly reduce the commercial marketing for food and beverages to children and to strategically increase the social marketing approaches to tackle childhood obesity.

Marketing is based on a very simple idea: putting the consumer—rather than production—at the heart of the business process. This simple but powerful concept underpins the effects marketing has had in encouraging childhood obesity; this chapter argues that, not only does this obesogenic marketing need to be reduced, but that the concepts as applied through social marketing can also guide efforts to combat childhood obesity.

Consumer focus is only part of the marketing story. Successful marketing begins with a critical analysis of the broad environmental factors that encourage individualized choices. The resulting insights guide the development of micro-level offers. Applying a marketing approach to the challenge of childhood obesity generates opportunities to make health-reinforcing behaviors desirable and accessible, and inform multi-sectoral, multi-disciplinary policy progress. To harness the power of marketing, however, its potential scope and force must first be recognized by the broad stake-holder community, and a marketing mindset applied from the beginning of the planning process.

This chapter begins by explaining the need for marketing thinking. It examines the evidence base on food promotion to children, which has not only established that there is an effect, but has also informed UK policy-makers in their decision to impose restrictions on unhealthy food marketing to children. This path has been well trodden by tobacco control, and the chapter goes on to identify significant learning points that emerge from this experience. Finally, drawing on tobacco control, commercial marketing and social marketing experiences, the chapter concludes with calls to reduce obesogenic marketing to children and to take social marketing-oriented strategic action. The necessary behavior changes to reverse the rising rates of childhood overweight and obesity will not be achieved by ad hoc, isolated interventions driven by the supply side (be that public policy or commercial interests). Comprehensive, large-scale interventions require strategic planning. Effective planning needs to be informed and shaped by the recognition that we are caught in both the firm grip of an obesogenic environment and a somewhat passive acceptance of the trend towards overweight and obesity as the norm, rather than the exception, by many lay persons, and indeed professionals. In this way marketing can indeed promote healthy weight.

Familiarity with customer desires and needs requires consistent and multi-method research. Marketers attempt to get inside our heads, see the world as we see it and adjust their offerings accordingly. Because people differ, this often means that a degree of customization is needed, so markets are segmented into homogenous subsets and target groups selected for bespoke attention. Customization also includes the choice of communication channels—and with the growing sophistication of electronic communication technologies the opportunities for segmentation even to individual level, becomes a reality. The only limits to innovation and the responsiveness of the commercial marketing mix are that shareholder value has to be enhanced. The key lesson is that meeting customer needs more accurately is good for business.

The need for this degree of sensitivity to the customer is quite simply because their behavior is voluntary. Marketers cannot force people to buy, so they have to engage, entice, persuade and seduce: the aim is to create motivational exchanges in which people will freely, indeed gladly, engage.

For marketers, children represent an important target group: their independent purchasing power makes them a valuable market in their own right; they also influence household purchase decisions and ultimately they represent tomorrow’s brand-loyal adult market.

It is challenging to put precise figures on these phenomena, but as a rough guide, the US Institute of Medicine Report on Food Marketing to Children and Youth1 suggested that one third of children’s annual $30 billion direct purchases were on food and beverages. In addition, the US Market for Kids’ Foods and Beverages, 2003 report estimated that children and adolescents influence $500 billion of purchase decisions at the household level.2 This represents more than half of the total US annual spending on food and beverages (estimated at $895.4 billion in the 2004 US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Food Expenditure Series).1

The public health community also has strong social and economic motivations to invest in influencing children’s purchase and consumption behaviors. The Foresight report projected a seven-fold increase in total societal costs for obesity in England to just under £50 billion by 2050.3 Many intervention campaigns want to ameliorate these projected trends by encouraging children and adults to accept added-value offerings—whether these are to eat more fruit and vegetables, cook or take exercise. And just as with breakfast cereals or soft drinks, individuals are free to accept or reject these offerings. The effectiveness of such public health initiatives is dependent on the voluntary action of the target audience. Public health therefore has to learn to be engaging, enticing, persuasive and seductive.

Sensitive research, customization and partnership working have to become second nature. The opportunities to intervene and encourage healthy diet and lifestyle choices using marketing theory and practice are only just beginning to be recognized and, therefore, the evidence on what works and what does not is still being amassed. There is however, much transferable experience and learning from other sectors that can be interpreted, adapted and applied in childhood obesity prevention. Two of the most valuable are current commercial marketing theory and practice, and retrospective analysis of tobacco control.

The power of marketing: the food business

In 2003, a systematic review of the literature on the extent, nature and effects of food promotion to children was commissioned by the Food Standards Agency.4 It concluded (see Box 15.1) that food was promoted to children more than any other product group, and that the types of food being advertised were consistently contrary to recommended dietary guidelines. Television was the dominant medium for this advertising, but the review noted the increasing importance other channels, including sponsorship, in-school marketing, point-of-sale materials and incentives, free gifts and samples, loyalty schemes, and new media in the communications mix.

The review also showed that this promotional activity does influence children’s food knowledge, preferences, behaviors and diet-related health status. It impacts on food categories (e.g., breakfast cereals) as well as specific branded items (e.g., particular pre-sweetened breakfast cereals). Furthermore, the influence is independent of other influencing variables such as parental behavior or pricing.

Box 15.1 The findings of reviews in relation to the extent and nature of food promotion

Source: Food Standards Agency, 20034

- Food dominates advertising to children.

- Five product categories dominate this advertising (soft drinks, pre-sugared cereals, confectionery, snacks and fast-food restaurants).

- The advertised diet contrasts dramatically with the recommended diet.

- Children engage with and enjoy this “unhealthy” advertising.

The findings in relation to the effects were that:

- Food promotion influences children’s nutritional knowledge, food preferences, purchasing and purchase-related behavior, consumption, and diet and health status.

- The extent of the influence is difficult to determine (though advertising is independent of other factors).

- Food promotion affects both total category sales and brand switching.

The review was updated for WHO in 20065 and 2009,6 taking in a global perspective. The updates showed that, while the more complex studies have all been undertaken in developed countries, children respond to advertising in much the same way across the globe. In fact, there is reason to believe that young people in poorer countries may be even more vulnerable to food promotion than their wealthier peers, because they are less advertising literate and associate developed countries’ brands with desirable attributes of life. They also provide a key entry point for multinationals because they are more flexible and responsive than their parents.

Following on from the first systematic review, research by the UK’s regulatory body for the communications industries, which includes broadcast advertising (Ofcom), also concluded that TV advertising influences children’s food behaviors and that restrictions on TV advertising were, therefore, warranted.7 These were phased in during 2007–8 and limited the advertising of high fat, salt, sugar (HFSS) foods (as defined by using the UK’s nutrient profiling system) on children’s TV programming and dedicated children’s channels.

Concerns were raised that the restrictions would accelerate the trend for marketing spend to shift from broadcast advertising to alternative (unregulated) marketing channels. There is evidence to support this in the initial Department of Health evaluation8 of the regulations, which show that a 41% decrease in HFSS television advertising to children is offset by a 42% increase in press advertising, and 11% increase in radio, cinema and internet advertising. In addition, a number of recent studies in the UK and internationally have analysed the content of food and beverage marketing in these other media, including children’s websites,9–11 children’s magazines,12 in-store promotions13 and direct mailings 14 and found that HFSS foods continue to predominate.

There has also been substantial research on parental responses to the influence of marketing on their children. There is a growing and consistent body of evidence that parents perceive food marketing as a driver of children’s food requests, and that it acts both as a barrier to their efforts to encourage healthy food choices and a source of parent–child conflict.15,16

In summary then, the power of marketing to encourage unhealthy behavior is well established. It is becoming clear, however, that it can also push in the opposite direction. Tobacco control provides some interesting insights into how restrictions on commercial marketing can be combined with proactive social marketing.

Tobacco control: ten marketing lessons

In 1954, when Richard Doll first published his research on British GPs showing the lethal qualities of tobacco, some 80% of UK men smoked and women were enthusiastically catching them up.17 Today cigarettes are used by fewer than a quarter of the UK population, and in other countries this proportion is well under a fifth.

Dietary behaviors and stakeholder responses are still in 1954. The full enormities of the pandemic of diet and inactivity-related non-communicable chronic diseases are just now being appreciated. Two things are already certain, however: the toll will continue to rise to at least match that from tobacco,18,19 and public health cannot afford to take fifty years to find an effective response. The purpose of learning lessons from tobacco is, therefore, to find short cuts to effective solutions.

Smoking, diet and physical activity are strongly influenced by a range of social, cultural and economic risk factors. In the case of less healthy eating patterns, such as excess consumption of fat, refined sugars and salt, there are also strong biological drivers. These biological drivers, although strongly embedded in our physiological “hard-wiring”, are nevertheless potentially responsive to interventions. Establishing the relative influences and how these interact is vital to our understanding of how to respond. However, we are unlikely ever to understand this perfectly, and, as Yach et al20 emphasize, we cannot delay taking action until we do. Good science can reduce uncertainty, it cannot produce certainty—nor can it make decisions for us. Rigorous, transparent reviews of the evidence and expert interpretation of the evidence base overall, however, does provide a substantial foundation from which to build well-informed policy response.

Restricting marketing, not just advertising

Several decades of research have shown beyond reasonable doubt that tobacco marketing is a significant causal factor in both the onset and continuance of young people’s smoking. Inevitably, this research focused initially on advertising and the other forms of marketing communications discussed above, but it has also looked at marketing more widely. This has resulted in controls on advertising being matched by controls on product design (through an EU Directive in tar levels), pricing (through taxation) and packaging (through mandated and increasingly prominent health warnings). There are also currently active debates about restricting the number of outlets and introducing generic packaging.21

Furthermore, this broader perspective shows that it is not just the impact of individual marketing tools that matters, but their cumulative effect. This is not surprising; marketing strategies are deliberately designed to be internally consistent and self-reinforcing. Typically, this effort is focused on developing and honing evocative brands, and recent research in the UK shows that these continue to drive youth smoking even after a complete ban on tobacco advertising.22

Lesson One: The power of marketing extends well beyond its most visible manifestations such as advertising. Controls on advertising in isolation will most likely move investment into the myriad of other marketing channels; regulatory controls and voluntary codes of conduct must take these realities into account.

Prevention and direct interventions

In recent years, tobacco control strategies have diverged. Australasia, North America and those parts of the developing world that are active in tobacco control have opted for population level strategies. The aim is to get the message out as widely as possible that smoking is a bad idea, that you should not take it up, and that if you have done, you should stop. In this way it harnesses social norms and Robert Cialdini’s notion that “most people will do the right thing if they believe it is the norm.”23

The UK has opted for a more intensive, clinically based approach of offering high quality smoking cessation services. However, they are labor intensive, so cannot reach large numbers of the population or have any significant impact on prevalence levels. They also soak up budgets: as Chapman points out, in the UK over recent years “five times more has been spent on assisting cessation than on trying to encourage more smokers to make quit attempts, and instil in them the confidence to do so” (Chapman, p. 141).24 He goes on to argue that this distortion of priorities has had a detrimental effect on outcomes: “in Australia and Canada two decades of quit campaigns see smoking prevalence today about 10 years ahead of where the UK is today”.

Lesson Two: Population level strategies are essential in the fight against obesity; they should never have to compete with clinical interventions for resources.

Working with industry

The potential for cooperation with the tobacco industry is extremely limited because there is so little common interest with public health. The tobacco control endgame is the elimination of tobacco use; no tobacco company is going to share this vision. Clive Bates, former CEO of the Action on Smoking and Health, took this thinking a step further advocating a “scream test” to check out any new policy option: if it makes the tobacco industry scream, it is probably worth doing.

Food, however, is not tobacco. It does not harm when used as intended, nor does anyone want to eliminate its consumption, so collaboration is, therefore, at least a theoretical possibility.

For joint working to succeed, public health needs to have clearly thought through its aims. What is the endgame? What should the food market to look like in 5, 25 and 50 years’ time? We also need to approach the task with our eyes open. The legally binding fiduciary responsibilities of corporations mean that they will only cooperate as long as it is in their shareholders’ interests. They cannot do otherwise. It is up to others to ensure that their actions genuinely benefit public health.

Therefore, unless we in obesity prevention and control have a clear set of aims to guide our thinking, collaboration with even well-intentioned partners in the corporate sector will, like a lump of metal too close to a compass, inadvertently drag us off course.

Lesson Three: Cooperation with industry is only productive if public health has clearly stated goals and monitors the public health impact of industry partners’ actions. Win-wins are possible but elusive.

A global response to a global problem

Those involved with tobacco control have long recognized the international dimensions of its task; global brands like Marlboro and Lucky Strike make it all too apparent. This has resulted in an established history of international working. Under the leadership of WHO this work has culminated in the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the world’s first public health treaty, which is in the process of laying down standards for effective tobacco control. The FCTC is also the world’s most successful treaty—with more signatories than any other.

Apart from its great geographical reach, the FCTC has the enormous advantage of bringing together experts from across the world to engage in a unified effort to tackle the tobacco pandemic. This ensures both collective learning and the capacity to assess and meet the varying needs of different parts of the world, especially those of low and middle income countries.

Obesity is equally insensitive to national boundaries, and Coca-Cola has the reach of Philip Morris International—so global solutions are also needed. The WHO review of the global impact of energy-dense food promotion5 shows that young people in low and middle income countries are also affected by it—and may indeed be particularly vulnerable. As countries develop and industrialize this problem is likely to get worse.

Lesson Four: there needs to be a “Framework Convention on Obesity Control” (or at least an International Code on Marketing to Children) to match the FCTC.

Know your customer

The success of the fast-food industry in purveying its products may be a cause for concern. However, it also presents a great opportunity. Public health can and should be analysing the success of Coke and taking lessons for their own campaigns and interventions. At base they are good at getting us to do things—influencing our voluntary consumer behavior; and public health is also in the voluntary behavior change business.

Unhealthy commercial marketing needs to be reduced, as noted above, but can also be counteracted by healthy social marketing.25

Lesson Five: the first step in successful social marketing is to listen to our customers and then devise offerings that genuinely meet their needs. If our efforts do not produce results, reach for the ear trumpet not the megaphone.

Emotion, branding and relationships

The power of branding is built on the recognition that human decision making is not just driven by rational logico-deductive reasoning. Emotions and heuristics (or short cuts) also play a big part: consuming chocolate is as much about sex as it is eating, and trips to the supermarket would be impossible if shoppers rationally weighed up the pros and cons of every choice.

Brands, which were initially devised to make the early corporations seem more human,26 provide a perfect vehicle for meeting these more subtle needs. They can make us feel happy as well as full, and cool as well as warmly clad. Public health can also use branding.27 The anti-tobacco Truth campaign offers a good example: it built up a degree of trust with young people in the USA and drove down smoking prevalence.28

Building brands takes time. Indeed as business has recognized for some decades, behavior change takes time and benefits greatly from continuity. There is much more money to be made if customers come back again and again. That is why supermarkets and airlines reward regulars with loyalty cards, special deals and chatty magazines. They have moved beyond mere exchanges and want to start building relationships with us. And all the evidence is that, despite their obvious mercenary motivations, it works. We do respond with brand loyalty and regular visits. This relational thinking can be applied equally well—if not better—in social marketing.29

Lesson Six: behavior change takes time—we should build brands and relationships.

The whole marketing mix

Behavior change takes more than communication. The importance of distinguishing between advertising and marketing when considering regulation has already been noted; it is equally important here. Eating and exercise behavior can be influenced by media campaigns—the evidence from tobacco control puts this beyond dispute 30–35—but it is equally clear that multi-faceted interventions are more powerful. A switch from burgers to carrots is more likely if the communications that boost the attractiveness of carrots are backed by pricing that reinforces this attraction and makes them affordable, distribution and packaging that makes them accessible, and a product that delivers satisfaction. Branding can then be used to confirm and enhance this satisfaction.

Lesson Seven: communications are only a small part of the game. Glossy advertising campaigns—especially isolated ones—are not the answer.

Context matters

The individual’s power to make decisions is limited by their social and environmental context. Visiting a fast-food outlet will partly reflect personal choice, but also the availability of alternatives, income, family circumstances and, harking back to social norms, the behavior of those around us. Marketers take careful note of this context and do their best to influence or adapt to it.

The tobacco industry, for instance, puts a great deal of effort and resource into liaising with policy-makers, and has had considerable success across Europe in ensuring that they make decisions that favor the industry.36 Similarly, the tobacco companies focus their efforts on retailers, stakeholders and potential allies (e.g., in the fight to fend off smoke-free laws) as well as final customers, to make sure the circumstances are as supportive as possible of their interests.

The importance of this debate for weight control is highlighted by the concept of the obesogenic environment. This is created by many actors—planners, the food industry, governments, other commercial operators—and all have to change their behaviors to deliver improvement in public health. The principles of bringing about these changes are the same as for ordinary citizens—listen to their needs and deliver.

Tobacco control has also managed to gain an extra degree of traction with policy-makers because of the collateral damage caused by second-hand smoke. Perhaps the nearest equivalent for obesity is the economic cost to everyone, which has begun to emerge as the external environment (from health service weighing scales to impact on post-operative complications) adapts to increases in size and excess weight among a section of the population.

Lesson Eight: good health is the product of many complex factors—including government policy, commercial marketing, education and wealth—as well as individual lifestyle choices, and progress will depend on action on all these fronts. Stakeholders are a key target group in social marketing.

Competitive analysis

In some instances, commercial stakeholders will not cooperate with public health, however seductive the approach. The tobacco industry has long resisted almost all attempts to control its marketing. The only solution in this case has been to legislate and, indeed, through the FCTC, to do so on a global basis. It remains to be seen whether obesity control will ultimately have to follow the same route as tobacco control, but nevertheless, studying the competition is a great way of learning how better to influence behavior.

Lesson Nine: competitive analysis is an invaluable tool. One of the principal reasons we have so many smokers and unhealthy eaters is that the commercial sector has been better at marketing than we have.

Research

Marketing depends on research: customer orientation; relationship building; stakeholder marketing and competitive analysis each needs to be informed by up-to-date intelligence about the people with whom we want to do business—or at least deal with—and the world that they and we inhabit. Research can also guide progress and help map the route to the final goal.

Thus marketing research acts as a navigational aid, to guide progress and aid decision making. It can and should transcend ad hoc interventions. Coca-Cola did not build its brand by conducting a randomized control trial, but gradually honed it by consistently delivering consumer satisfaction and developing its understanding of its customers and stakeholders. Public health should adopt a similarly long-term and flexible approach to research.

Lesson Ten: research is a navigational aid that will help us to understand our customers and stakeholder.

Marketing has a great deal to offer the fight against childhood obesity, and the lessons learned from tobacco control need to be applied to obesity. The first priority is to reduce the pressure of commercial marketing of HFSS foods and beverages on children. This should be matched with well-informed social marketing interventions at all levels of the interlocking obesogenic system to encourage healthy behaviors. These activities should be coherent, research led and strategic; Box 15.2 presents a planning tool for ensuring that they are.

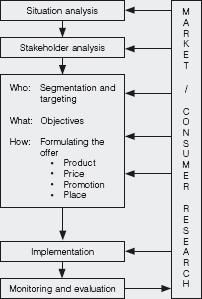

The diagram illustrates three key characteristics of marketing planning. The first reflects what might be called its gestalt. Seen as a whole, the plan becomes more than the sum of its parts. It provides a progressive process of learning about the market and its particular exchanges. This learning takes place within particular initiatives. For example, a systematically produced and carefully researched healthy eating initiative for school children will enable social marketers to improve their understanding of school children and their desires, and thereby to enhance the initiative. There are parallels here with building brand equity in a commercial context. Continuously refining and improving the product offered in response to target audience feedback can establish and deepen the relationship between parties. Deeper understanding enables marketers to reflect more closely the values and aspirations of their target population.

Box 15.2 A social marketing plan

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree