13.2 PRIMARY SURVEY

During the primary survey life-threatening conditions are identified. Assessment follows the familiar ABC pattern with significant additions.

Catastrophic External Haemorrhage

In military trauma management <C> ABC has become the established approach for casualty care following blast or significant penetrating trauma. For children too, obvious external exsanguinating haemorrhage must be identified and managed immediately.

Airway and Cervical Spine

Airway assessment following trauma has the highest priority and should follow the standard technique discussed in Chapters 4 and 5.

LOOK

LISTEN

FEEL

If the child is unconscious, uncooperative or has had a significant mechanism of injury that makes it possible for there to be a spinal injury, the head and neck should be stabilised initially by manual immobilisation. A hard collar should be fitted and applied to all cooperative patients.

Some situations are particularly difficult. An injured child may be uncooperative for many reasons including fear, pain or hypoxia. Manual immobilisation should be maintained and the contributing factors addressed. Too rigid immobilisation of the head in such cases may increase leverage on the neck as the child struggles. The infant or baby who is too small for a hard collar should have manual immobilisation supported throughout.

Breathing

After dealing with any immediate airway problems, breathing should be assessed as the next priority. As discussed in earlier chapters, the adequacy of breathing is checked in three domains – the effort of breathing, the efficacy of breathing and the effects of inadequate respiration on other organ systems. These are summarised in the box. When examining the chest, the ‘look, listen and feel’ approach is again appropriate, but it is important to remember to percuss also to distinguish a tension pneumothorax from a massive haemothorax.

- Recession

- Respiratory rate

- Inspiratory or expiratory noises

- Grunting

- Accessory muscle use

- Flaring of the nostrils

- Breath sounds

- Chest expansion

- Abdominal excursion

- Check for pneumo/haemothorax

- Heart rate

- Skin colour

- Mental status

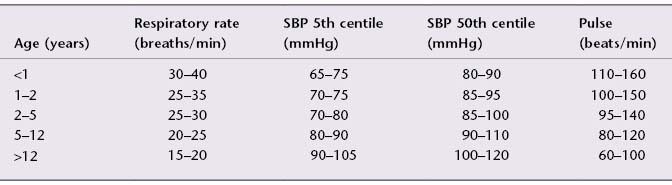

The normal resting respiratory rate changes with age. These changes are summarised in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 Vital signs: approximate range of normal respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and pulse at rest.

Circulation

Circulatory assessment in the primary survey involves the rapid assessment of heart rate and rhythm, pulse volume and peripheral perfusion (colour, temperature and capillary return, remembering that exposure to cold prolongs the capillary refill time in healthy people – test on the sternum). In addition, a rapid check should be made for significant external haemorrhage (and pressure applied if appropriate). Blood pressure takes too long to perform as part of the primary survey itself, but it should be measured as an adjunct (afterwards or in parallel by other personnel). An abnormal respiratory rate and altered mental status in the presence of circulatory compromise indicate the effect of shock on other organ systems. Using these measures, an estimate of the need for fluid replacement can be made (Table 13.2). Again, remember the caveats about heart rate, differential pulse volume and capillary refill time outlined in Chapter 7. It can be difficult to assess the circulatory state of an injured child: in blunt trauma large blood losses are the exception rather than the rule. A single abnormal sign is not predictive of shock, but more than two of the signs tending to the same conclusion is predictive of the requirement for fluid replacement (Table 13.2).

Table 13.2 Recognition of clinical signs indicating blood loss requiring urgent treatment.

| Sign | Indicator |

| Heart rate | Marked or increasing tachycardia or relative bradycardia |

| Systolic blood pressure | Falling (late sign) |

| Capillary refill time (normal <2 seconds) | Increased to >4–5 seconds |

| Respiratory rate | Tachypnoea unrelated to thoracic problem |

| Mental state | Altered conscious level unrelated to head injury |

Circulatory assessment must take into account the fact that resting heart rate, blood pressure and respiratory rate vary with age. The normal values are shown in Table 13.1. Note that the systolic blood pressure in children who have been injured is raised above normal, and that the degree of hypertension is unrelated to age or trauma severity. The clinician should therefore view with suspicion a systolic pressure in the lower part of the normal range in an injured child.

Disability

The assessment of disability during the primary survey consists of a brief neurological examination to determine the conscious level and to assess pupil size and reactivity. The conscious level is described by the child’s response to voice and (where necessary) to pain. The AVPU method describes the child as alert, responding to voice, responding to pain or unresponsive and is a rapid, if crude, assessment.

| A | ALERT |

| V | Responds to VOICE |

| P | Responds only to PAIN |

| U | UNRESPONSIVE to all stimuli |

If the child does not respond to voice, then a painful stimulus is needed. If the child responds to pain, it is best to note what the eyes and limbs did and what sounds or words were uttered, rather than simply categorising the child as ‘P’. Simple descriptions that will form the basis of a subsequent formal Glasgow Coma Score assessment, such as ‘opening eyes to pain’ or ‘localising to pain’, are much more informative than ‘P’ alone (pp. 176 and 177). The score will identify whether or not there is an abnormality of the child’s conscious level and alert the clinician to the possible need for airway protection if the level is ‘P’ or ‘U’.

Exposure

In order to assess a seriously injured child fully, it is necessary to remove his or her clothes. Children become cold very quickly, and may be acutely embarrassed when undressed in front of strangers. Although exposure is necessary the duration should be minimised, and a blanket provided at all other times.

Conditions Identified

By the end of the primary survey, the following conditions may have been recognised and should be treated as soon as they are found:

- Airway obstruction.

- Tension pneumothorax.

- Open pneumothorax.

- Massive haemothorax.

- Flail chest.

- Cardiac tamponade.

- Shock (haemorrhagic or otherwise).

- Decompensating head injury.

13.3 RESUSCITATION

Catastrophic External Haemorrhage

Catastrophic external haemorrhage must be managed immediately. In this situation, applying direct pressure with a dressing pad, applying a tourniquet to a limb, or packing an open wound with a haemostatic substance must be done instantly.

Airway and Cervical Spine

Airway

The airway may be compromised by material in the lumen (blood, vomit, teeth, a foreign body), by damage to or loss of control of the structures in the wall (mouth, tongue, pharynx, larynx, trachea) or by external compression or distortion from outside the wall (e.g. compression from a pre-vertebral haematoma in the neck or distortion from a displaced maxillary fracture). The commonest cause is from occlusion by the tongue in an unconscious, head-injured child. Whatever the cause, airway management should follow the sequence described in Chapters 4 and 5 bearing in mind the need to protect the cervical spine. This is summarised in the box.

- Jaw thrust (avoid chin lift)

- Suction/removal of foreign body under direct vision

- Oropharyngeal airways

- Tracheal intubation

- Surgical airway

Head tilt/chin lift is not recommended following trauma, because cervical spine injuries may be made worse.

Cervical Spine

For any mechanism of injury capable of causing spinal injury (or in cases with an uncertain history), the cervical spine is presumed to be at risk until it can be cleared. Children (and adults) can suffer spinal cord injury despite normal plain radiographs. If ignored, ligamentous instability without radiographic evidence of a fracture can have devastating consequences.

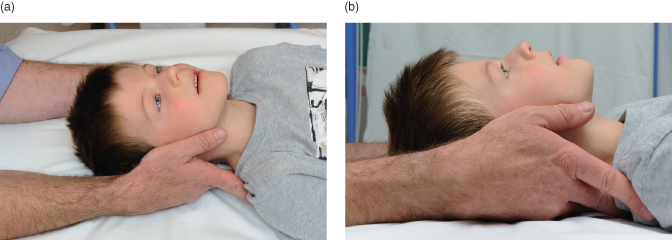

If a cervical spine injury is suspected the child should be immobilised initially by manual in-line stabilisation (Figure 13.2) and then by using an appropriately sized hard collar if tolerated (Figure 13.3). Too rigid immobilisation of the head may increase leverage on the neck as the child struggles (see further details in Sections 17.7–17.12). It is imperative that the child is treated from the outset in a gentle, supportive atmosphere in a way that is appropriate for their age, and that parents remain at the bedside, so that anxiety is minimised and unnecessary interventions are avoided.

Vomiting poses an obvious threat to the unprotected airway, especially if there is also a risk of spinal injury. Positioning the child safely and providing airway suction are the key interventions if the child vomits. If the child has only just arrived and the head, chest, pelvis and legs are still strapped securely to a spine board, then it is feasible to tilt the board temporarily while clearing the airway. Once the body straps have been removed, turning the child into the lateral position puts the spine at risk, unless it can be carried out immediately by three or four carers as a properly coordinated log-roll (Figure 13.4). It is generally much simpler and more effective to tip the trolley head-down (so that the trachea runs ‘uphill’) and provide suction to the mouth and pharynx.

If the spine has not been cleared, manual in-line immobilisation will be needed for intubation if indicated. Intubation is significantly harder with the collar left on, as jaw opening is hindered. Having weighed up the risk of failed intubation against any benefit of the collar being left in place, it is generally accepted that manual in-line immobilisation with the collar off is by far the best option. Immobilisation with the collar reapplied is necessary after securing the endotracheal tube. The cervical collar may only be removed when radiographs are normal, the child has no neck pain and the neurological examination is normal.

Clearly, if the child is paralysed, sedated and ventilated, the neurological examination cannot be done and spinal immobilisation may need to be maintained for prolonged periods. In such cases, a two piece collar such as a Philadelphia or an Aspen collar should be used for prolonged immobilisation. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be necessary to assess the risk to the spinal cord in this event.

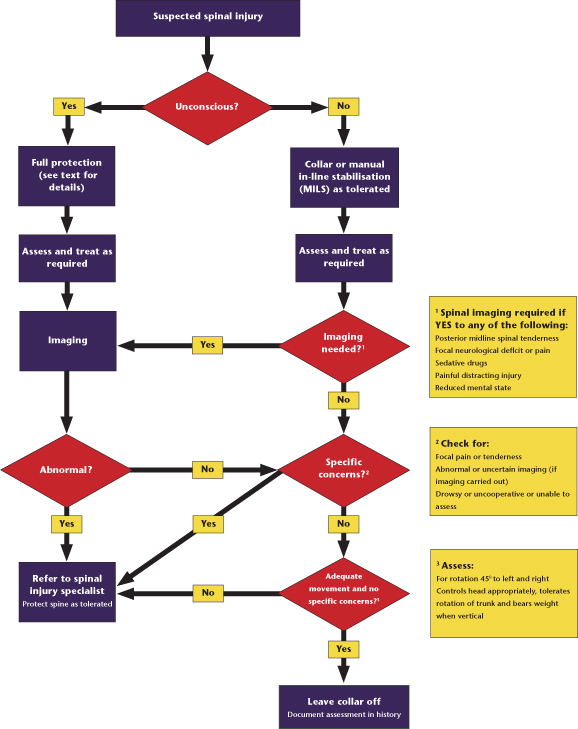

It is important to ensure that the cervical collar does not restrict venous outflow in the neck as this may increase intracranial pressure. See Figure 13.5 for the management and clearance of the cervical spine. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 17.

Breathing

If breathing is inadequate, ventilation must be commenced. Initially, bag–mask ventilation should be performed. Generally speaking, a child who requires bag–mask ventilation initially following trauma will subsequently require intubation to control the airway. Following intubation, mechanical ventilation can be commenced.

The indications for intubation and mechanical ventilation are summarised in the box below.

- Persistent airway obstruction

- Predicted airway obstruction, e.g. inhalational burn

- Loss of airway reflexes

- Inadequate ventilatory effort or increasing fatigue

- Disrupted ventilatory mechanism, e.g. severe flail chest

- Persistent hypoxia despite supplemental oxygen

- Controlled ventilation as part of the management of raised intracranial pressure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree