Grunting may be caused by the convulsion and not be a sign of respiratory distress in this instance.

- Efficacy of breathing:

- chest expansion/abdominal excursion,

- breath sounds – reduced or absent, and symmetry on auscultation, and

- SpO2 in air.

- chest expansion/abdominal excursion,

- Effects of respiratory failure on other physiology:

- heart rate,

- skin colour, and

- mental status.

- heart rate,

Circulation

- Heart rate: the presence of an inappropriate bradycardia suggests raised intracranial pressure.

- Pulse volume.

- Blood pressure: significant hypertension indicates a possible cause for the convulsion or more likely is a result of it.

- Capillary refill time.

- Skin temperature and colour.

- Effects on breathing and mental status.

- Monitor heart rate/rhythm, blood pressure and oximetry.

Disability

- Mental status/conscious level (AVPU score).

- Pupillary size and reaction (see Table 11.2).

- Posture: decorticate or decerebrate posturing in a previously normal child should suggest raised intracranial pressure. These postures can be mistaken for the tonic phase of a convulsion. Consider also the possibility of a drug-induced dystonic reaction or psychogenic pseudoseizures.

- Look for neck stiffness in a child and a full fontanelle in an infant, which suggest meningitis.

Exposure

- Rash: if one is present, ascertain if it is purpuric as an indicator of meningococcal disease or non-accidental injury.

- Fever: a fever is suggestive evidence of an infectious cause (but its absence does not suggest the opposite) or poisoning with ecstasy, cocaine or salicylates. Hypothermia suggests poisoning with barbiturates or ethanol.

- Consider the evidence for poisoning: history or characteristic smell (see Appendix H).

12.4 RESUSCITATION

Airway

- A patent airway is the first requisite. If the airway is not patent it should be opened and maintained with an airway manoeuvre or an airway adjunct.

- Even if the airway is open, the oropharynx may need secretion clearance by gentle suction.

- If the child is breathing satisfactorily, the recovery position should be adopted to minimise the risk of aspiration of vomit.

Breathing

- All convulsing children should receive high-flow oxygen through a face mask with a reservoir as soon as the airway has been demonstrated to be adequate.

- If the child is hypoventilating, respiration should be supported with oxygen via a bag–valve–mask device and consideration given to intubation and ventilation.

Circulation

- Gain intravenous or intraosseous access.

- Take blood for a bedside glucose and laboratory test. If in doubt or a test is unavailable, it is safer to treat as if hypoglycaemia (<3 mmol/L) is present: give a bolus intravenously of 2 mL/kg 10% glucose, followed by an infusion containing glucose, e.g. 5 mL/kg/h of 10% glucose with 0.45% saline. Without the follow-on infusion there is a risk of rebound hypoglycaemia, which may also occur with larger bolus doses of glucose.

- If hypoglycaemia is a new condition for the child additional blood and urine samples will be required to investigate the cause. Ideally, the blood sample should be taken before treating with glucose. This will allow later investigation of the cause of the hypoglycaemic state.

- Give a 20 mL/kg rapid bolus of crystalloid to any child with signs of shock. Start an antibiotic such as cefotaxime for those in whom a diagnosis of septicaemia is suggested by the presence of a purpuric rash after blood has been taken for culture.

- Give an antibiotic such as cefotaxime or ceftriaxone to any child in whom a diagnosis of meningitis is suggested by a stiff neck or bulging fontanelle after blood has been taken for culture.

12.5 SECONDARY ASSESSMENT AND LOOKING FOR KEY FEATURES

While the primary assessment and resuscitation are being carried out, a focused history of the child’s health and activity over the previous 24 hours and any significant previous illness should be gained. Specific points for history taking include:

- Current febrile illness.

- Recent trauma.

- History of epilepsy.

- Poison ingestion.

- Last meal.

- Known illnesses.

The immediate emergency treatment requirement, after ABC stabilisation and exclusion or treatment of hypoglycaemia is to stop the convulsion.

12.6 EMERGENCY TREATMENT OF THE CONVULSION

This evidence-based consensus guideline is not intended to cover all circumstances. There are patients with recurrent convulsive status whose physicians recognise that they respond to certain drugs and not to others and for these children an individual protocol is more appropriate. In addition, seizures in neonates are managed differently to those of infants and children.

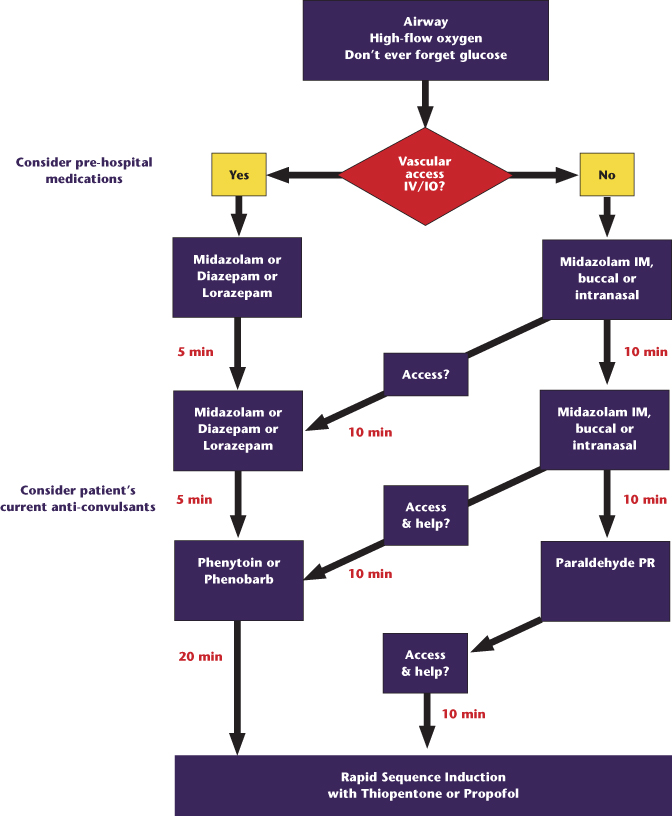

The algorithm shown in Figure 12.1 (overleaf) is for the majority of children in CSE who present acutely on wards or in an emergency department. It is not applicable to non-convulsive status epilepticus.

Figure 12.1 Status epilepticus algorithm. IM, intramuscular; IO, intraosseous; IV, intravenous; PR, per rectum.

Step 1 is undertaken 5 minutes after the seizure has started.

Step 1

- Reassess ABC.

- Bedside glucose should be checked immediately.

- If in a pre-hospital setting or intravenous access is not established and if the seizure has lasted longer than 5 minutes, give intramuscular midazolam; alternatives include buccal/intranasal midazolam or rectal diazepam.

- If intravenous access is already established or can be established quickly, give intravenous midazolam or diazepam or lorazepam.

Step 2

- If the convulsion continues, follow the algorithm (Figure 12.1), give a second dose of benzodiazepine and call for senior help.

- Continue to attempt to obtain vascular access.

- Start to prepare phenytoin or phenobarbitone for step 3.

- Reconfirm it is an epileptic seizure.

In the majority of children, the treatment in steps 1 and 2 will be effective.

Step 3

At this stage senior help is needed to reassess the child and advise on management. It is also wise to seek anaesthetic or intensive care advice as the child will need anaesthetising and intubating if this step is unsuccessful.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree