- Gestational age

- Causes and management of preterm labour

- Survival and outcome for the preterm infant

- Preterm delivery at the margins of viability

- Stabilization at birth and management in the ‘golden hour’

- Common problems to be expected in the preterm infant

- Supportive care on the NICU

- Preparation for discharge home

Introduction

About 7–8% of all births are born preterm (<37 weeks’ gestation). Preterm births account for the majority of work on most neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and preventing preterm birth has become the foremost challenge for obstetric practice today. The burden to society of preterm births is enormous – because of the expensive and lengthy intensive care required and the potential for long-term neurodisability in survivors. However, expert and careful intervention to support these infants in the immediate neonatal period also offers the opportunity to generate a lifetime of good-quality survival from what initially may be a life-threatening situation.

Gestational Age

Establishing the exact gestational age is sometimes difficult and so for many years, especially in the USA, classification and outcome studies have been based on birthweight, which is measureable. However, it is clear that survival and neurodevelopmental outcome are more strongly determined by the degree of prematurity than by birthweight. Most recent studies and treatment protocols therefore use gestational age. Degrees of prematurity are defined in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Gestational age bands and their incidence

| Gestational age (weeks after LMP) | Terminology | Approximate incidence (as % singleton live births)a |

| >42 weeks | Post term | 4 |

| 37–42 weeks | Term | 90 |

| <37 weeks | Preterm | 6–8 |

| 34–36 weeks | Mildly pretermb | 4.9 |

| 32–34 weeks | Moderately pretermb | 0.8 |

| 28–32 weeks | Very pretermb | |

| <28 weeks | Extreme preterm | 0.4 |

| ≤24 weeks | Threshold of viability | 0.14 |

a The frequency of preterm birth is much higher in multiples (twins, triplets, etc.).

b The definitions of these gestation bands vary between different countries and authors.

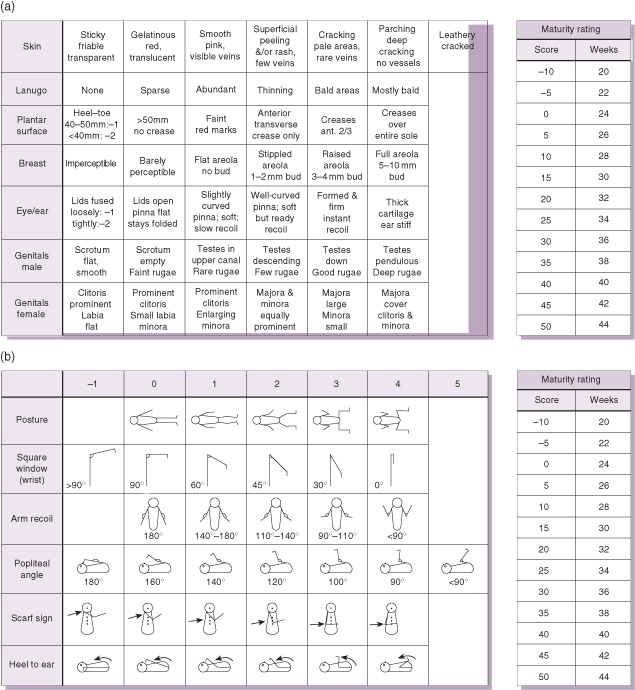

Gestational age can now be accurately determined by a first-trimester ultrasound ‘dating scan’. If there is a big discrepancy between this and the estimated date of delivery (EDD) calculated from the mother’s last menstrual period (LMP), or if there is an unbooked or concealed pregnancy, the gestation can be estimated by performing an objective examination of the newborn baby. The new Ballard examination (based on the original Dubowitz examination) is recommended. This quantifies six neurological and six physical parameters and should be performed with the baby fully exposed under a radiant heat warmer (see Fig. 11.1).

Figure 11.1 The expanded new Ballard score.

Reproduced with permission from Ballard JL, Khoury JC, Wedig K, et al. New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. J Pediatr 1991;119:417–423.

Causes and Management of Preterm Labour

Risk Factors for Preterm Labour

The risk factors for preterm labour are shown in Table 11.2. In some cases labour can be suppressed (see below), but in many preterm delivery becomes inevitable. The biggest global causes of prematurity are social deprivation and multiple pregnancy: 6% of singletons, 51% of twins and 91% of triplets are delivered preterm. Infection is strongly implicated in 25–40% of preterm labour – evidence of chorioamnionitis is found in more than 50% of deliveries at less than 25 weeks. In some cases the ‘cause’ of preterm labour cannot be established.

Table 11.2 Risk factors for preterm labour and prematurity

| Factor | Comment |

| Maternal age | Extremes of age (<18 yrs or >35 yrs) are associated with preterm labour |

| Maternal ethnicity | Afro-Caribbean mothers have a 15% incidence of preterm labour |

| Multiple pregnancy | The higher the multiple, the greater the chance of preterm delivery |

| Infection | Chorioamnionitis is strongly associated with extreme preterm labour |

| Hypertension, PET | Labour often induced early to maintain maternal health |

| Cervical weakening | Previous mid-trimester pregnancy loss or cervical surgery (e.g. cone biopsy) |

| Uterine malformation | Bicornuate uterus or massive fibroids |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | Abruption or placenta previa |

| Amniotic fluid volume | Polyhydramnios and oligohydramnios are both risk factors |

| Maternal substance abuse | Alcohol, cocaine and cigarette smoking all associated with preterm labour |

| Fetal abnormality | Congenital anomalies and trisomies associated with preterm delivery |

Predicting Preterm Delivery

Accurate prediction of imminent preterm delivery allows targeted intervention and transfer, but is not yet an exact science. The following may be useful:

- Ultrasound measurement of the length of the cervix – cervical shortening is associated with a high risk of delivery.

- Fetal fibronectin (a glycoprotein produced by the fetus and act as ‘biological glue’); its presence in vaginal/cervical secretions in mid-trimester is highly predictive of preterm labour, but is not valid in the presence of ruptured membranes.

- Frequency and duration of regular contractions.

Clinical Management of Preterm Labour

Although the high mortality and morbidity associated with preterm delivery have prompted a great deal of research into ways of predicting preterm birth, only limited benefits have resulted. Where possible, the woman in preterm labour at less than 32 weeks’ gestation should be transferred to a perinatal unit where optimal delivery, stabilization and subsequent management of her infant can be carried out. In utero transfer should only be attempted when the preterm labour is not advanced or can be safely and effectively suppressed with tocolytic agents (see Chapter 25).

When a patient is admitted with a diagnosis of possible ‘preterm labour’, the management plan depends on the criteria listed in Box 11.1.

- Is the patient in active preterm labour?

- Is there an underlying cause for the onset of labour?

- Should steroids be given to the mother to enhance fetal lung maturity?

- Should drugs be used to reduce uterine activity?

- Are the mother and fetus at risk of infection?

- Where is the baby to be delivered?

- How is the baby to be delivered?

- Is a suitable neonatal intensive care cot available?

Obstetric management of preterm labour is rarely clear-cut and is a balanced decision between the relative risks to mother and fetus of continuing the pregnancy versus those of early delivery. Suppression of preterm labour is sometimes possible using tocolytic agents such as beta-adrenergic agonists (e.g. ritodrin), calcium channel blockers (e.g. nifedipine), oxytocin receptor antagonists (e.g. atosiban) or COX-2 cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors (e.g. indometacin). These can delay preterm delivery by 2–7 days but have not been shown to reduce neonatal mortality or morbidity. Magnesium sulphate does not delay delivery but reduces the risk of cerebral palsy in the preterm infant.

Temporary suppression of labour may ‘buy time’ for in utero transport to a perinatal centre or for the acceleration of fetal lung maturity with two doses of corticosteroids. Betamethasone has been shown to be associated with fewer adverse effects than dexamethasone. Meta-analyses have consistently shown that corticosteroids given for 48 h before delivery significantly reduce the incidence and severity of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and the incidence of intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), and possibly improve neurodevelopmental outcome. Suppression of labour is contraindicated in the presence of intrauterine infection, congenital anomaly, signs of fetal compromise or significant antepartum haemorrhage.

Mode of Delivery in Preterm Labour

Caesarean Section or Vaginal Delivery

If delivery is inevitable then the best mode of delivery must be chosen. Where the mother’s life is in danger (e.g. pre-eclampsia) urgent caesarean section is indicated. Where delivery is elective (e.g. for severe intrauterine growth retardation, IUGR) a balance must be struck between the risks to the fetus of labour and vaginal delivery and the risk to the mother from a caesarean section. In very early gestations (<26 weeks) a lower segment caesarean section (LSCS) may not be possible and a classical (vertical incision) caesarean is needed. This carries a greater risk of uterine rupture in future pregnancies.

Preterm Breech Presentation

Many extreme preterm babies are still in the breech position when the mother enters labour. The preferred mode of delivery for the preterm breech fetus has been the subject of considerable controversy. The hazards to the fetus of vaginal breech delivery include difficulty with delivery of the head and, rarely, entrapment of the aftercoming head. Although caesarean section in the preterm breech may be associated with some difficulties, it is probably the preferred method of delivery beyond 25 weeks’ gestation.

Survival and Outcome for the Preterm Infant

Decision-making in the management of the extremely preterm delivery is influenced by the improved short- and long-term outcomes observed with advances in perinatal care. Aggressive obstetric management and intervention for fetal reasons in late second-trimester deliveries is now practised in many tertiary perinatal centres, and these attitudes are partly responsible for the improved outcomes obtained. Units should develop their own guidelines for the management of extremely preterm labour.

Short-Term Survival and Outcome

Published survival rates vary markedly from country to country and from centre to centre. Large geographically based population studies offer the least biased data. It is important to consider the following points:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree