In children, coma is caused by a diffuse metabolic insult (including cerebral hypoxia and ischaemia) in 95% of cases, and by structural lesions in the remaining 5%. Metabolic disturbances can produce diffuse, incomplete and asymmetrical neurological signs falsely suggestive of a localised lesion. Early signs of metabolic encephalopathy may be subtle, with reduced attention and blunted affect. The conscious level in metabolic encephalopathies is often quite variable from minute to minute. The most common causes of coma are summarised in the box overleaf.

- Hypoxic ischaemic brain injury following respiratory or circulatory failure

- Epileptic seizures

- Trauma:

- intracranial haemorrhage

- cerebral oedema

- intracranial haemorrhage

- Infections:

- meningitis

- encephalitis

- cerebral and extracerebral abscesses

- malaria

- meningitis

- Intoxication

- Metabolic:

- renal or hepatic failure

- hypo- or hypernatraemia

- hypoglycaemia

- hypothermia

- hypercapnia

- inherited metabolic disease

- renal or hepatic failure

- Cerebrovascular event, secondary to arteriovascular malformation or tumour

- Cerebral tumour

- Hydrocephalus, including blocked intraventricular shunts

11.2 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

In very young children, before the cranial sutures are closed, considerable intracranial volume expansion may occur if the process is slow (i.e. hydrocephalus). However, if the process is rapid and in children with a fixed volume cranium, increase in volume due to brain swelling, haematoma or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) blockage will cause raised intracranial pressure (ICP). Initially CSF and venous blood within the cranium decrease in volume. Soon, this compensating mechanism fails and as the ICP continues to rise the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) falls and cerebral arterial blood flow is reduced.

where MAP is mean arterial pressure. Reduced CPP reduces cerebral blood flow (CBF). Normal CBF is over 50 mL/100 g brain tissue/min. If the CBF falls below 20 mL/100 g brain tissue/min, the brain suffers ischaemia. The aim is to keep CPP above 50–60 mmHg (6.5–8 kPa) depending on age.

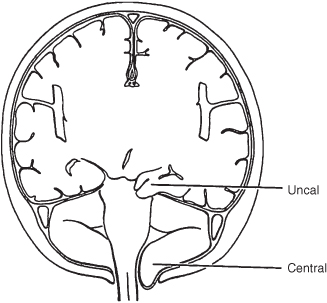

Increasing ICP will push brain tissue against more rigid intracranial structures. Two clinical syndromes are recognisable by the site of localised brain compression (Figure 11.1).

Central Syndrome

The whole brain is pressed down towards the foramen magnum and the cerebellar tonsils herniate through it (‘coning’). Neck stiffness may be noted. A slow pulse, raised blood pressure and irregular respiration leading to apnoea are seen terminally, usually preceded by significant tachycardia.

Uncal Syndrome

The intracranial volume increase is mainly in the supratentorial part of the intracranial space. The uncus, which is part of the hippocampal gyrus, is forced through the tentorial opening and compressed against the fixed free edge of the tentorium. If the pressure is unilateral (e.g. from a subdural or extradural haematoma), this leads to third nerve compression and an ipsilateral dilated pupil. Next, an external oculomotor palsy appears, so the eye cannot move laterally. Hemiplegia may then develop on either or both sides of the body, depending on the progression of the herniation.

11.3 PRIMARY ASSESSMENT OF THE CHILD WITH DECREASED CONSCIOUS LEVEL

The first steps in the management of the child with decreased conscious level are to assess and if necessary support the airway, breathing and circulation. This will ensure that the diminished conscious level is not secondary to hypoxia and/or ischaemia and that whatever the cerebral pathology it will not be worsened by lack of oxygenated blood supply to the brain. This is dealt with in Chapter 7. Below is a summary.

Airway

- Assess vocalisations: crying or talking indicate ventilation and some degree of airway patency.

- Assess airway patency by:

- looking for chest and/or abdominal movement, symmetry and recession,

- listening for breath sounds and stridor, and

- feeling for expired air.

- looking for chest and/or abdominal movement, symmetry and recession,

- Reassess after any airway-opening manoeuvres. If there is still no evidence of air movement, then airway patency can be assessed by giving rescue breaths (see Chapter 4).

Breathing

- Effort of breathing:

- Efficacy of breathing:

- chest expansion/abdominal excursion,

- breath sounds – reduced or absent, and symmetry on auscultation, and

- SpO2 in air.

- chest expansion/abdominal excursion,

- Effects of respiratory failure on other physiology:

- heart rate,

- skin colour, and

- mental status.

- heart rate,

Circulation

- Heart rate: the presence of an inappropriate bradycardia will suggest raised ICP.

- Pulse volume.

- Blood pressure: significant hypertension indicates a possible cause for the coma or may be a result of it.

- Capillary refill time.

- Skin temperature and colour.

- Effects on breathing and mental status: acidotic sighing respirations may suggest metabolic acidosis from diabetes, an inborn error of metabolism, or salicylate or ethylene glycol poisoning as a cause for the coma.

Disability

- Mental status/conscious level (AVPU score).

- Pupillary size and reaction (Table 11.2).

- Posture: decorticate or decerebrate posturing in a previously normal child should suggest raised ICP.

- Look for neck stiffness in a child and a full fontanelle in an infant, which suggest meningitis.

- The presence of convulsive movements should be sought; these may be subtle.

- There should be a specific assessment for raised ICP. There are very few absolute signs of raised ICP, these being papilloedema, a bulging fontanelle and the absence of venous pulsation in retinal vessels. All three signs are often absent in acutely raised ICP.

- In a previously well, unconscious child (Glasgow Coma Scale score <9) who is not in a postictal state, the signs in the box below are suggestive of raised ICP.

Table 11.2 Summary of pupillary changes.

| Pupil size and reactivity | Cause |

| Small reactive pupils | Metabolic disorders |

| Medullary lesion | |

| Pinpoint pupils | Metabolic disorders |

| Narcotic/organophosphate ingestions | |

| Fixed midsize pupils | Midbrain lesion |

| Fixed dilated pupils | Hypothermia |

| Severe hypoxia | |

| Barbiturates (late sign) | |

| During and post seizure | |

| Anticholinergic drugs | |

| Unilateral dilated pupil | Rapidly expanding ipsilateral lesion |

| Tentorial herniation | |

| Third nerve lesion | |

| Epileptic seizures |

- When the head is turned to the left or right a normal response is for the eyes to move away from the head movement; an abnormal response is no (or random) movement

- When the head is flexed, a normal response is deviation of the eyes upward; a loss of conjugate upward gaze is a sign suggestive of raised ICP

- Decorticate (flexed arms, extended legs)

- Decerebrate (extended arms, extended legs)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree