Fetal Lie

The relation of the fetal long axis to that of the mother is termed fetal lie and is either longitudinal or transverse. Occasionally, the fetal and the maternal axes may cross at a 45-degree angle, forming an oblique lie. This lie is unstable and becomes longitudinal or transverse during labor. A longitudinal lie is present in more than 99 percent of labors at term. Predisposing factors for transverse fetal position include multiparity, placenta previa, hydramnios, and uterine anomalies (Chap. 23, p. 468).

Fetal Presentation

Fetal Presentation

The presenting part is that portion of the fetal body that is either foremost within the birth canal or in closest proximity to it. It typically can be felt through the cervix on vaginal examination. Accordingly, in longitudinal lies, the presenting part is either the fetal head or breech, creating cephalic and breech presentations, respectively. When the fetus lies with the long axis transversely, the shoulder is the presenting part. Table 22-1 describes the incidences of the various fetal presentations.

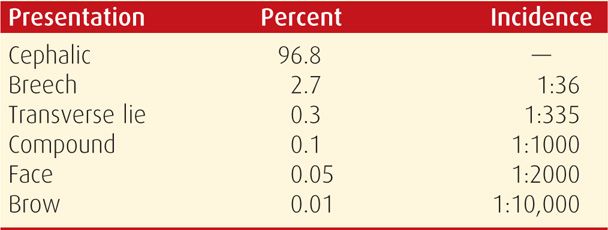

TABLE 22-1. Fetal Presentation in 68,097 Singleton Pregnancies at Parkland Hospital

Cephalic Presentation

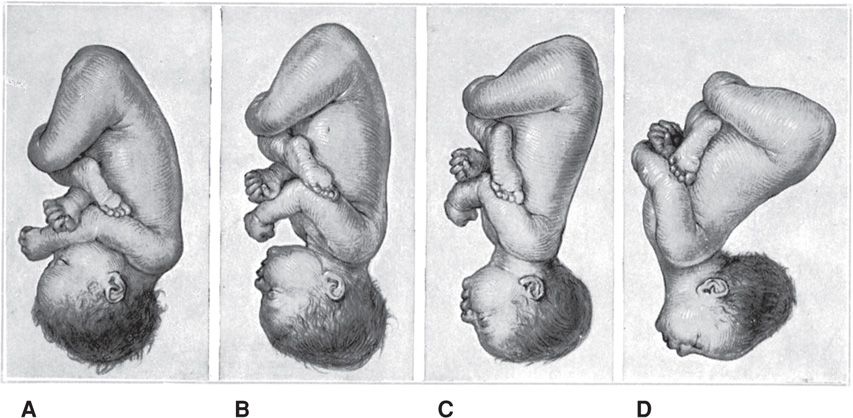

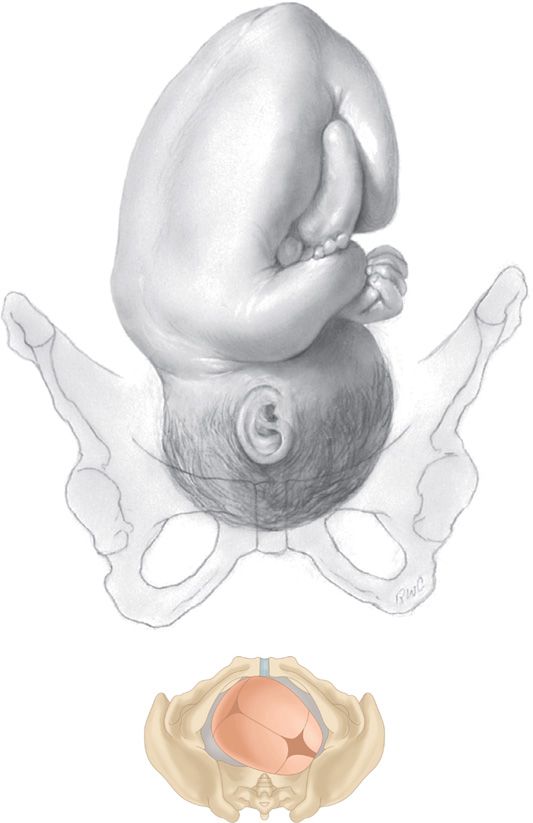

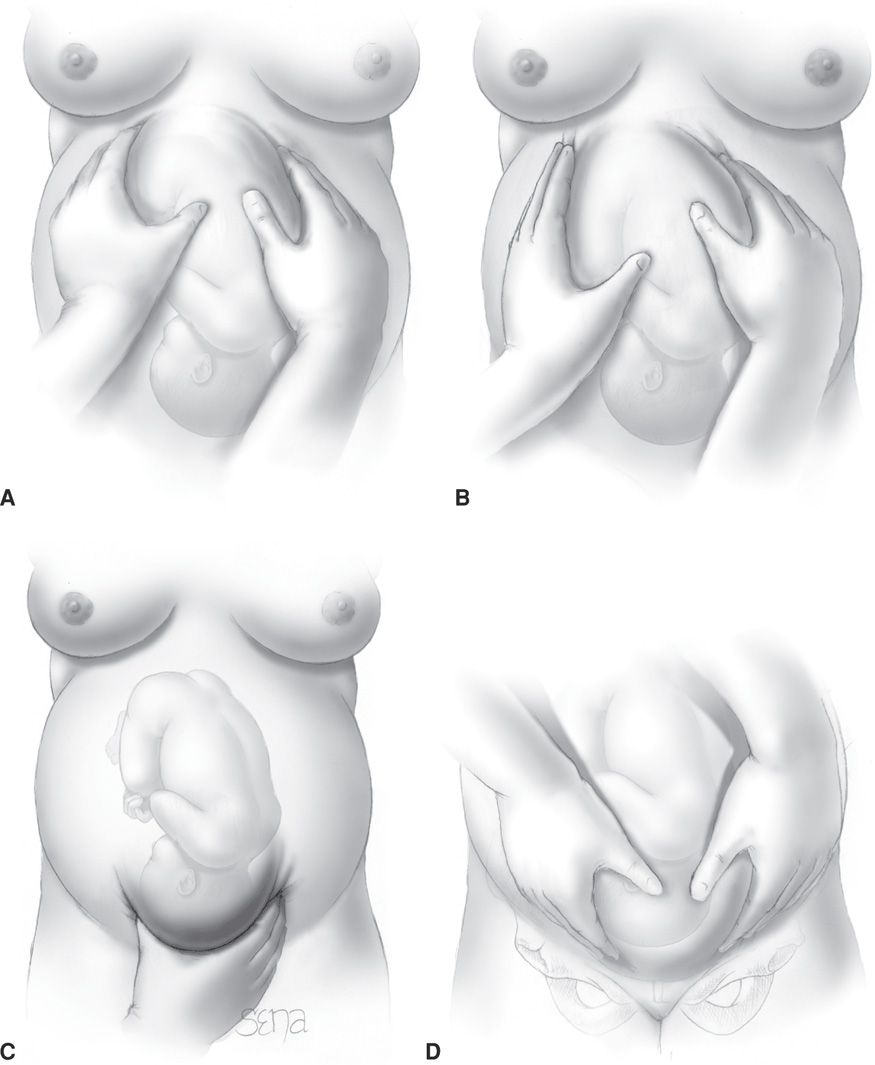

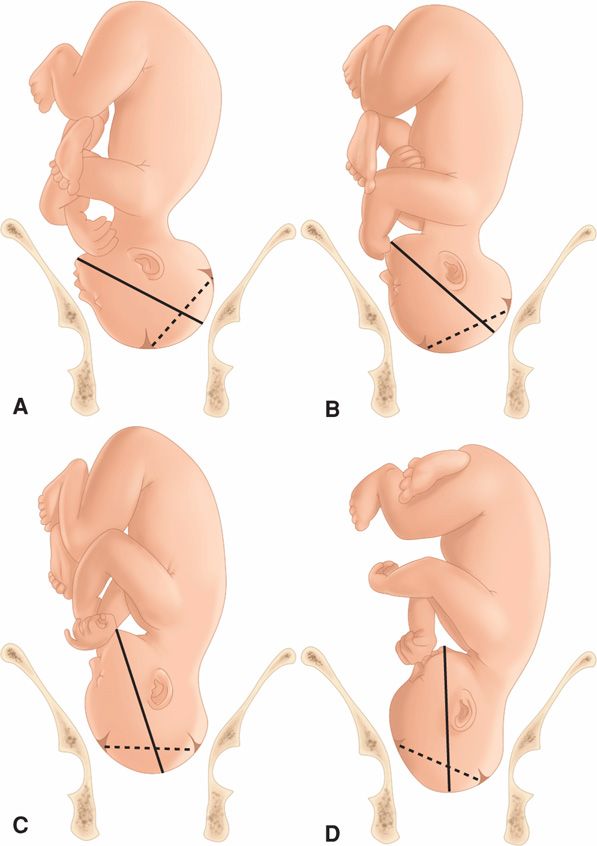

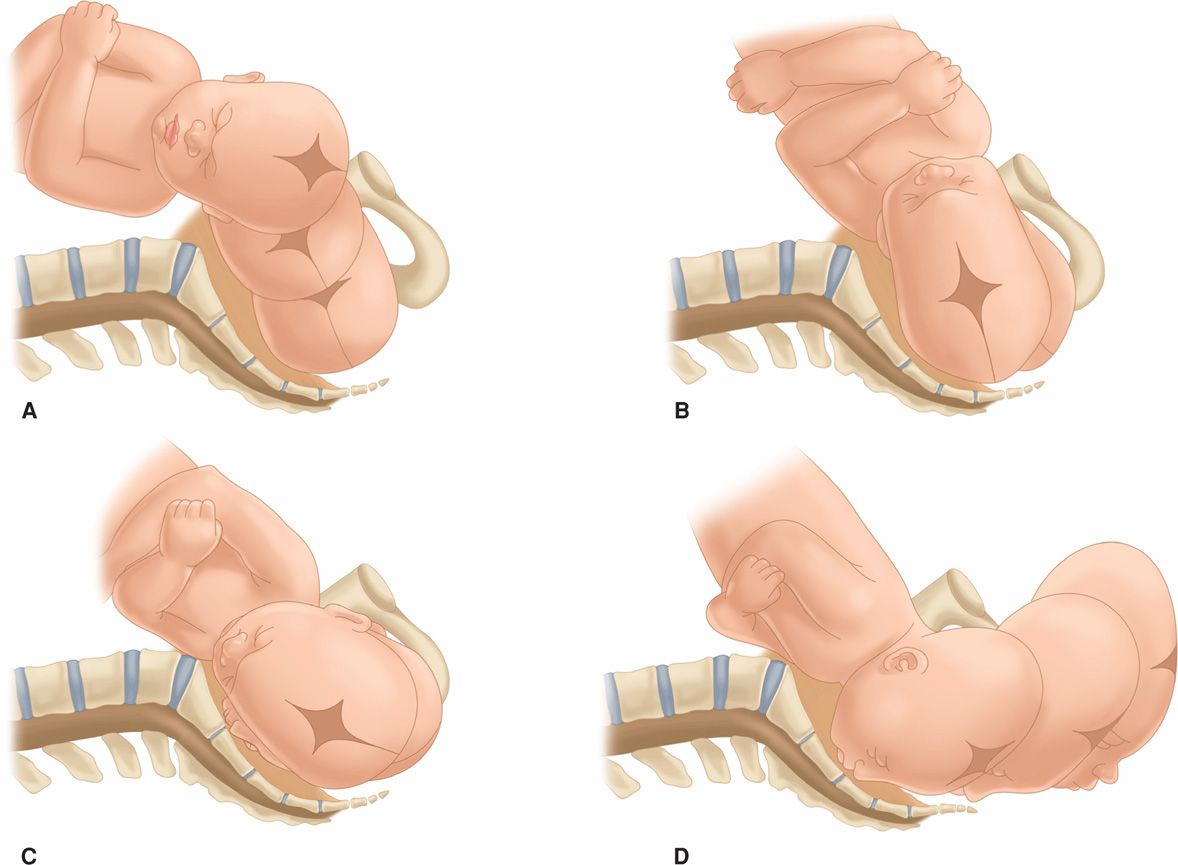

Such presentations are classified according to the relationship between the head and body of the fetus (Fig. 22-1). Ordinarily, the head is flexed sharply so that the chin is in contact with the thorax. The occipital fontanel is the presenting part, and this presentation is referred to as a vertex or occiput presentation. Much less commonly, the fetal neck may be sharply extended so that the occiput and back come in contact, and the face is foremost in the birth canal—face presentation (Fig. 23-6, p. 466). The fetal head may assume a position between these extremes, partially flexed in some cases, with the anterior (large) fontanel, or bregma, presenting—sinciput presentation—or partially extended in other cases, to have a brow presentation (Fig. 23-8, p. 468). These latter two presentations are usually transient. As labor progresses, sinciput and brow presentations almost always convert into vertex or face presentations by neck flexion or extension, respectively. Failure to do so can lead to dystocia, as discussed in Chapter 23 (p. 455).

Figure 22-1 Longitudinal lie. Cephalic presentation. Differences in attitude of the fetal body in (A) vertex, (B) sinciput, (C) brow, and (D) face presentations. Note changes in fetal attitude in relation to fetal vertex as the fetal head becomes less flexed.

The term fetus usually presents with the vertex, most logically because the uterus is piriform or pear shaped. Although the fetal head at term is slightly larger than the breech, the entire podalic pole of the fetus—that is, the breech and its flexed extremities—is bulkier and more mobile than the cephalic pole. The cephalic pole is composed of the fetal head only. Until approximately 32 weeks, the amnionic cavity is large compared with the fetal mass, and the fetus is not crowded by the uterine walls. Subsequently, however, the ratio of amnionic fluid volume decreases relative to the increasing fetal mass. As a result, the uterine walls are apposed more closely to the fetal parts.

If presenting by the breech, the fetus often changes polarity to make use of the roomier fundus for its bulkier and more mobile podalic pole. As discussed in Chapter 28 (p. 559), the incidence of breech presentation decreases with gestational age. It approximates 25 percent at 28 weeks, 17 percent at 30 weeks, 11 percent at 32 weeks, and then decreases to approximately 3 percent at term. The high incidence of breech presentation in hydrocephalic fetuses is in accord with this theory, as the larger fetal cephalic pole requires more room than its podalic pole.

Breech Presentation

When the fetus presents as a breech, the three general configurations are frank, complete, and footling presentations and are described in Chapter 28 (p. 559). Breech presentation may result from circumstances that prevent normal version from taking place. One example is a septum that protrudes into the uterine cavity (Chap. 3, p. 42). A peculiarity of fetal attitude, particularly extension of the vertebral column as seen in frank breeches, also may prevent the fetus from turning. If the placenta is implanted in the lower uterine segment, it may distort normal intrauterine anatomy and result in a breech presentation.

Fetal Attitude or Posture

Fetal Attitude or Posture

In the later months of pregnancy, the fetus assumes a characteristic posture described as attitude or habitus as shown in Figure 22-1. As a rule, the fetus forms an ovoid mass that corresponds roughly to the shape of the uterine cavity. The fetus becomes folded or bent upon itself in such a manner that the back becomes markedly convex; the head is sharply flexed so that the chin is almost in contact with the chest; the thighs are flexed over the abdomen; and the legs are bent at the knees. In all cephalic presentations, the arms are usually crossed over the thorax or become parallel to the sides. The umbilical cord lies in the space between them and the lower extremities. This characteristic posture results from the mode of fetal growth and its accommodation to the uterine cavity.

Abnormal exceptions to this attitude occur as the fetal head becomes progressively more extended from the vertex to the face presentation (see Fig. 22-1). This results in a progressive change in fetal attitude from a convex (flexed) to a concave (extended) contour of the vertebral column.

Fetal Position

Fetal Position

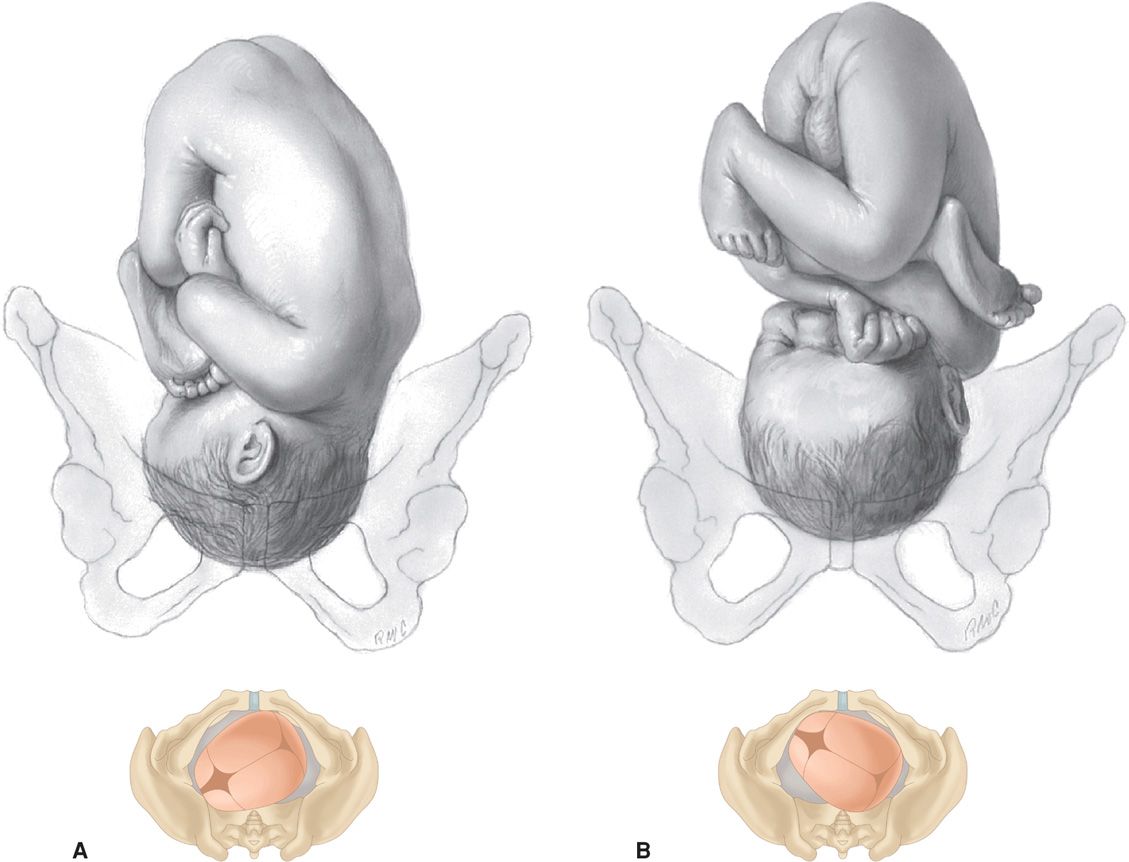

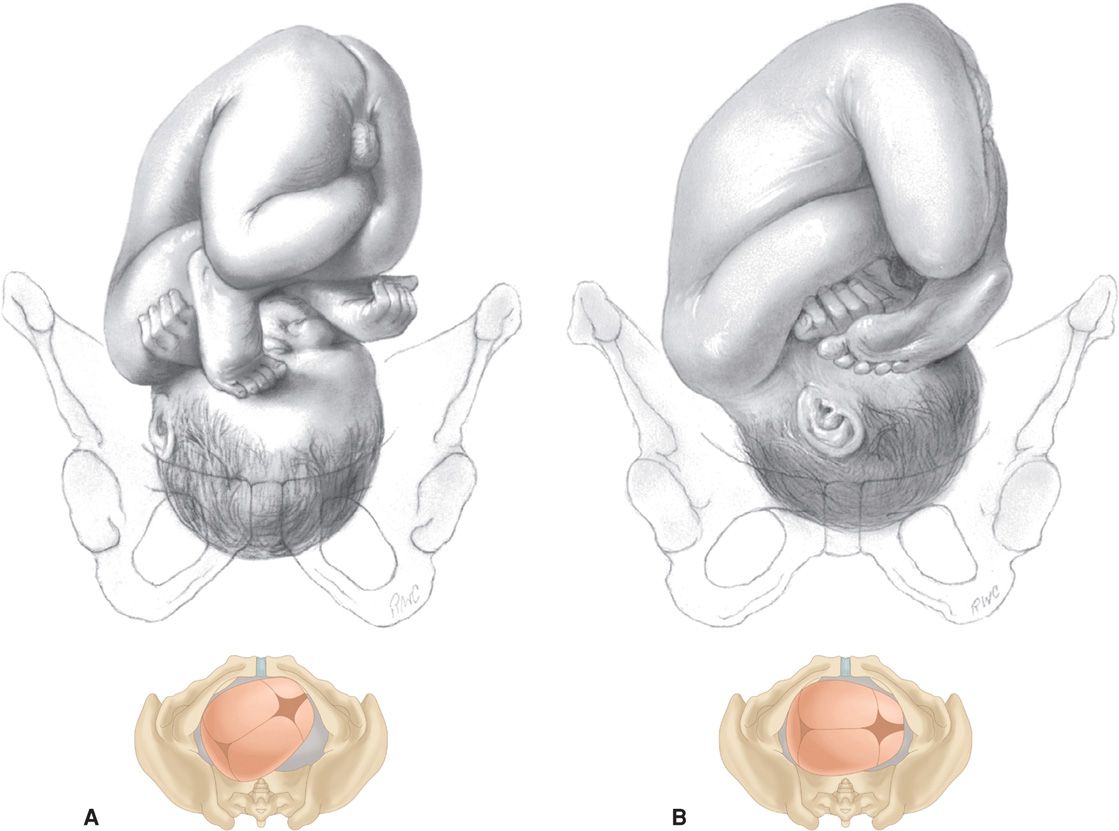

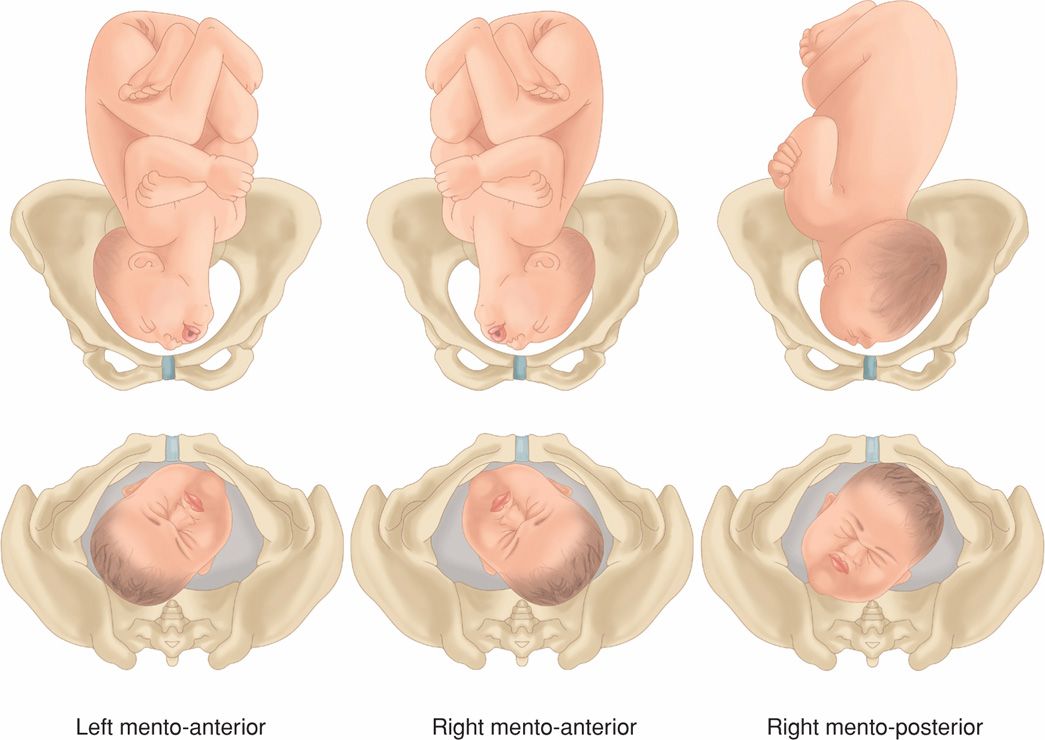

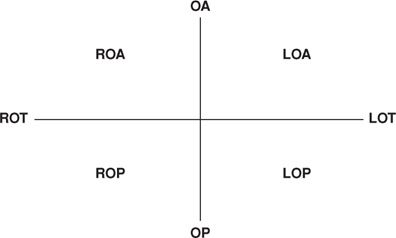

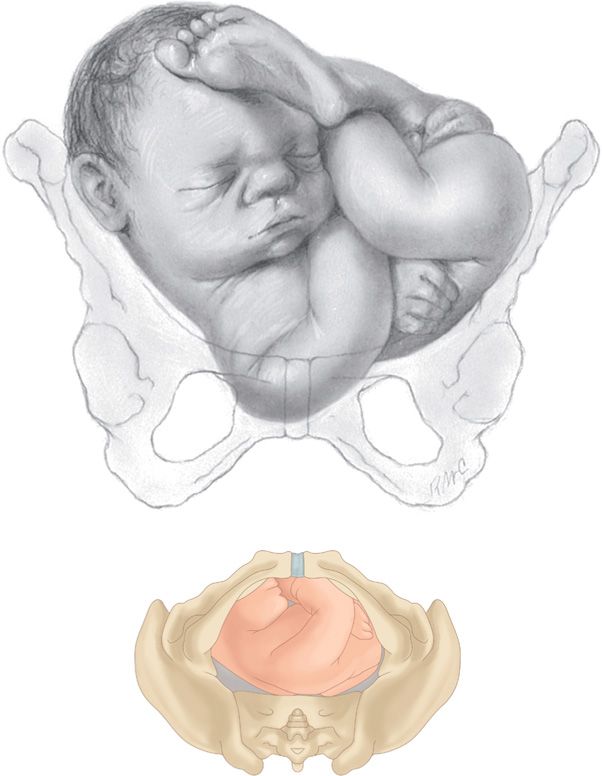

Position refers to the relationship of an arbitrarily chosen portion of the fetal presenting part to the right or left side of the birth canal. Accordingly, with each presentation there may be two positions—right or left. The fetal occiput, chin (mentum), and sacrum are the determining points in vertex, face, and breech presentations, respectively (Figs. 22-2 to 22-6). Because the presenting part may be in either the left or right position, there are left and right occipital, left and right mental, and left and right sacral presentations. These are abbreviated as LO and RO, LM and RM, and LS and RS, respectively.

FIGURE 22-2 Longitudinal lie. Vertex presentation. A. Left occiput anterior (LOA). B. Left occiput posterior (LOP).

FIGURE 22-3 Longitudinal lie. Vertex presentation. A. Right occiput posterior (ROP). B. Right occiput transverse (ROT).

FIGURE 22-4 Longitudinal lie. Vertex presentation. Right occiput anterior (ROA).

FIGURE 22-5 Longitudinal lie. Face presentation. Left and right mentum anterior and right mentum posterior positions.

FIGURE 22-6 Longitudinal lie. Breech presentation. Left sacrum posterior (LSP).

Varieties of Presentations and Positions

Varieties of Presentations and Positions

For still more accurate orientation, the relationship of a given portion of the presenting part to the anterior, transverse, or posterior portion of the maternal pelvis is considered. Because the presenting part in right or left positions may be directed anteriorly (A), transversely (T), or posteriorly (P), there are six varieties of each of the three presentations as shown in Figures 22-2 to 22-6. Thus, in an occiput presentation, the presentation, position, and variety may be abbreviated in clockwise fashion as:

Approximately two thirds of all vertex presentations are in the left occiput position, and one third in the right.

In shoulder presentations, the acromion (scapula) is the portion of the fetus arbitrarily chosen for orientation with the maternal pelvis. One example of the terminology sometimes employed for this purpose is illustrated in Figure 22-7. The acromion or back of the fetus may be directed either posteriorly or anteriorly and superiorly or inferiorly. Because it is impossible to differentiate exactly the several varieties of shoulder presentation by clinical examination and because such specific differentiation serves no practical purpose, it is customary to refer to all transverse lies simply as shoulder presentations. Another term used is transverse lie, with back up or back down, which is clinically important when deciding incision type for cesarean delivery (Chap. 23, p. 468).

FIGURE 22-7 Transverse lie. Right acromiodorsoposterior (RADP). The shoulder of the fetus is to the mother’s right, and the back is posterior.

Diagnosis of Fetal Presentation and Position

Diagnosis of Fetal Presentation and Position

Several methods can be used to diagnose fetal presentation and position. These include abdominal palpation, vaginal examination, auscultation, and, in certain doubtful cases, sonography. Rarely, plain radiographs, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be used.

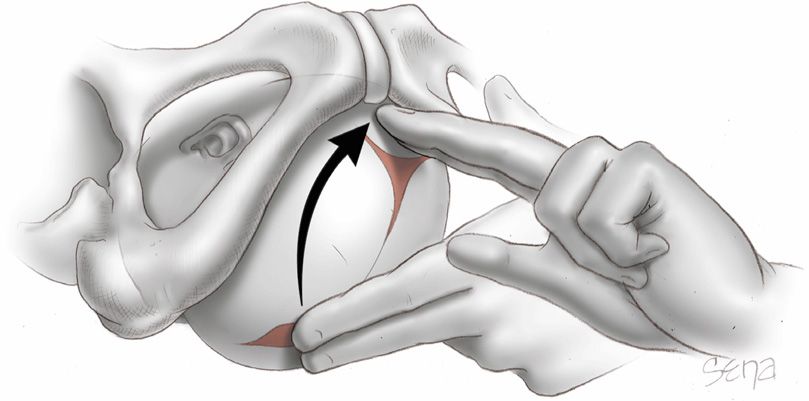

Abdominal Palpation—Leopold Maneuvers

Abdominal examination can be conducted systematically employing the four maneuvers described by Leopold in 1894 and shown in Figure 22-8. The mother lies supine and comfortably positioned with her abdomen bared. These maneuvers may be difficult if not impossible to perform and interpret if the patient is obese, if there is excessive amnionic fluid, or if the placenta is anteriorly implanted.

FIGURE 22-8 Leopold maneuvers (A–D) performed in a fetus with a longitudinal lie in the left occiput anterior position (LOA).

The first maneuver permits identification of which fetal pole—that is, cephalic or podalic—occupies the uterine fundus. The breech gives the sensation of a large, nodular mass, whereas the head feels hard and round and is more mobile and ballottable.

Performed after determination of fetal lie, the second maneuver is accomplished as the palms are placed on either side of the maternal abdomen, and gentle but deep pressure is exerted. On one side, a hard, resistant structure is felt—the back. On the other, numerous small, irregular, mobile parts are felt—the fetal extremities. By noting whether the back is directed anteriorly, transversely, or posteriorly, fetal orientation can be determined.

The third maneuver is performed by grasping with the thumb and fingers of one hand the lower portion of the maternal abdomen just above the symphysis pubis. If the presenting part is not engaged, a movable mass will be felt, usually the head. The differentiation between head and breech is made as in the first maneuver. If the presenting part is deeply engaged, however, the findings from this maneuver are simply indicative that the lower fetal pole is in the pelvis, and details are then defined by the fourth maneuver.

To perform the fourth maneuver, the examiner faces the mother’s feet and, with the tips of the first three fingers of each hand, exerts deep pressure in the direction of the axis of the pelvic inlet. In many instances, when the head has descended into the pelvis, the anterior shoulder may be differentiated readily by the third maneuver.

Abdominal palpation can be performed throughout the latter months of pregnancy and during and between the contractions of labor. With experience, it is possible to estimate the size of the fetus. According to Lydon-Rochelle and colleagues (1993), experienced clinicians accurately identify fetal malpresentation using Leopold maneuvers with a high sensitivity—88 percent, specificity—94 percent, positive-predictive value—74 percent, and negative-predictive value—97 percent.

Vaginal Examination

Before labor, the diagnosis of fetal presentation and position by vaginal examination is often inconclusive because the presenting part must be palpated through a closed cervix and lower uterine segment. With the onset of labor and after cervical dilatation, vertex presentations and their positions are recognized by palpation of the various fetal sutures and fontanels. Face and breech presentations are identified by palpation of facial features and fetal sacrum, respectively.

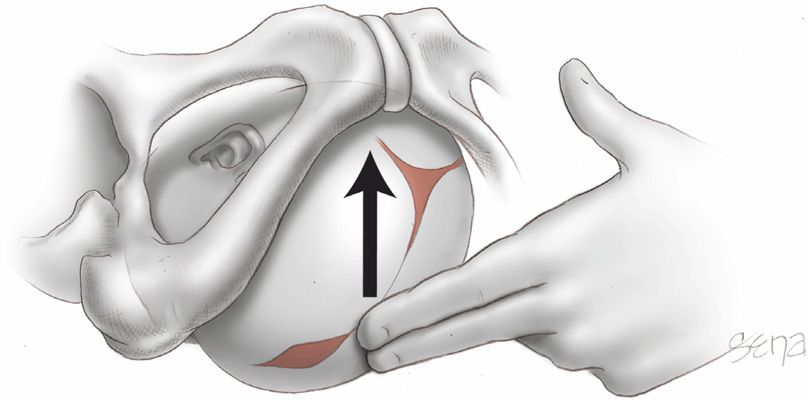

In attempting to determine presentation and position by vaginal examination, it is advisable to pursue a definite routine, comprising four movements. First, the examiner inserts two fingers into the vagina and the presenting part is found. Differentiation of vertex, face, and breech is then accomplished readily. Second, if the vertex is presenting, the fingers are directed posteriorly and then swept forward over the fetal head toward the maternal symphysis (Fig. 22-9). During this movement, the fingers necessarily cross the sagittal suture and its linear course is delineated. Next, the positions of the two fontanels are ascertained. For this, fingers are passed to the most anterior extension of the sagittal suture, and the fontanel encountered there is examined and identified. Then, with a sweeping motion, the fingers pass along the suture to the other end of the head until the other fontanel is felt and differentiated (Fig. 22-10). Last, the station, or extent to which the presenting part has descended into the pelvis, can also be established at this time (p. 449). Using these maneuvers, the various sutures and fontanels are located readily (Fig. 7-11, p. 139).

FIGURE 22-9 Locating the sagittal suture by vaginal examination.

FIGURE 22-10 Differentiating the fontanels by vaginal examination.

Sonography and Radiography

Sonographic techniques can aid fetal position identification, especially in obese women or in women with rigid abdominal walls. Zahalka and associates (2005) compared digital examinations with transvaginal and transabdominal sonography for fetal head position determination during second-stage labor and reported that transvaginal sonography was superior.

Occiput Anterior Presentation

Occiput Anterior Presentation

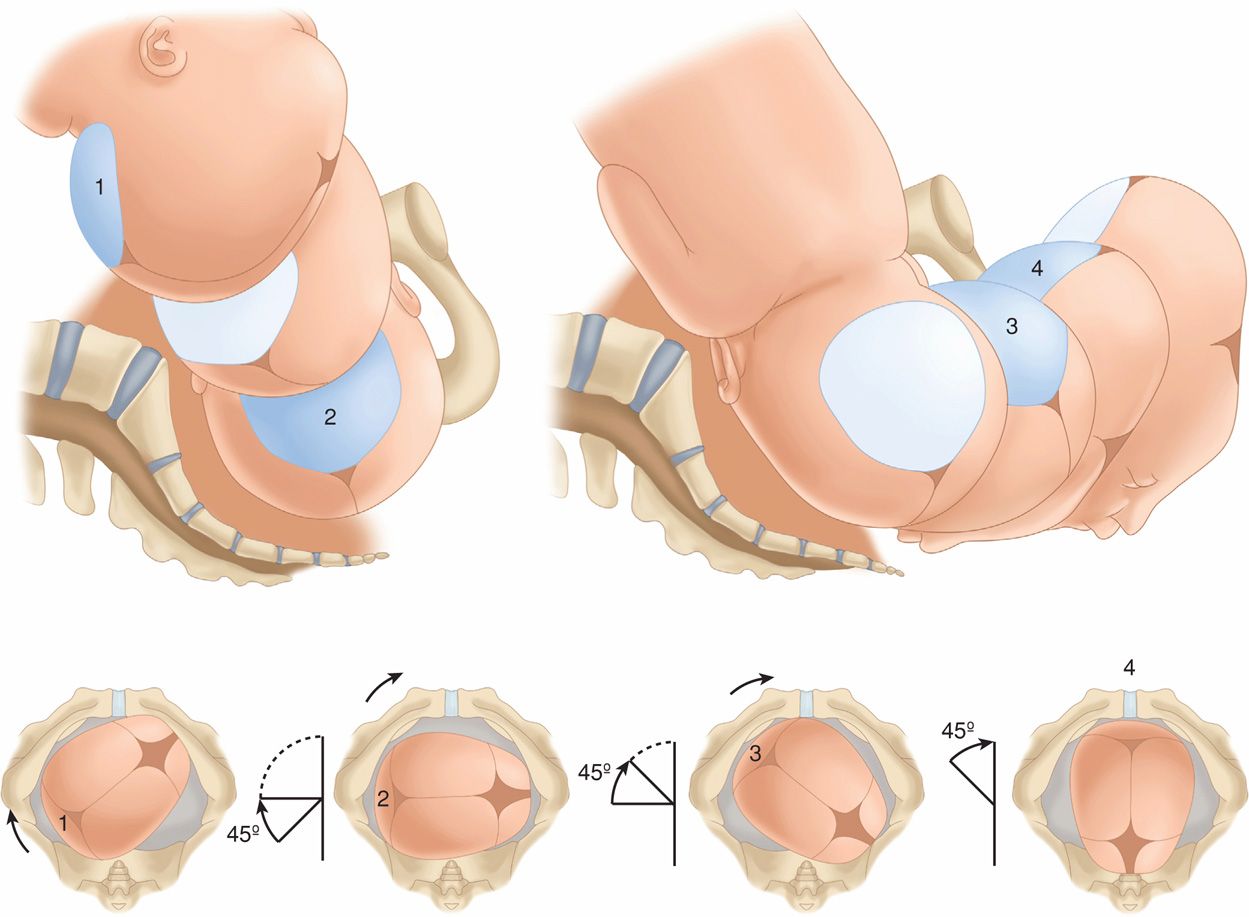

In most cases, the vertex enters the pelvis with the sagittal suture lying in the transverse pelvic diameter. The fetus enters the pelvis in the left occiput transverse (LOT) position in 40 percent of labors and in the right occiput transverse (ROT) position in 20 percent (Caldwell, 1934). In occiput anterior positions—LOA or ROA—the head either enters the pelvis with the occiput rotated 45 degrees anteriorly from the transverse position, or this rotation occurs subsequently. The mechanism of labor in all these presentations is usually similar.

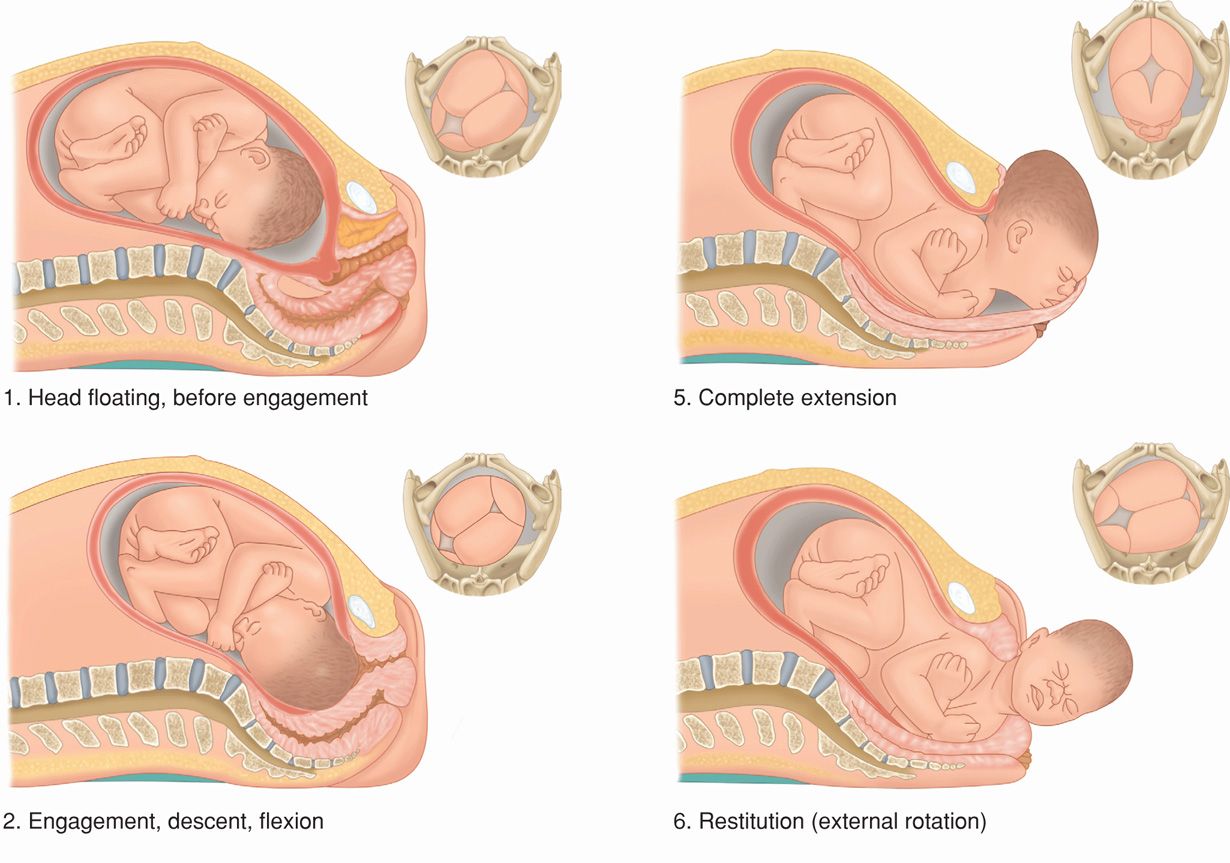

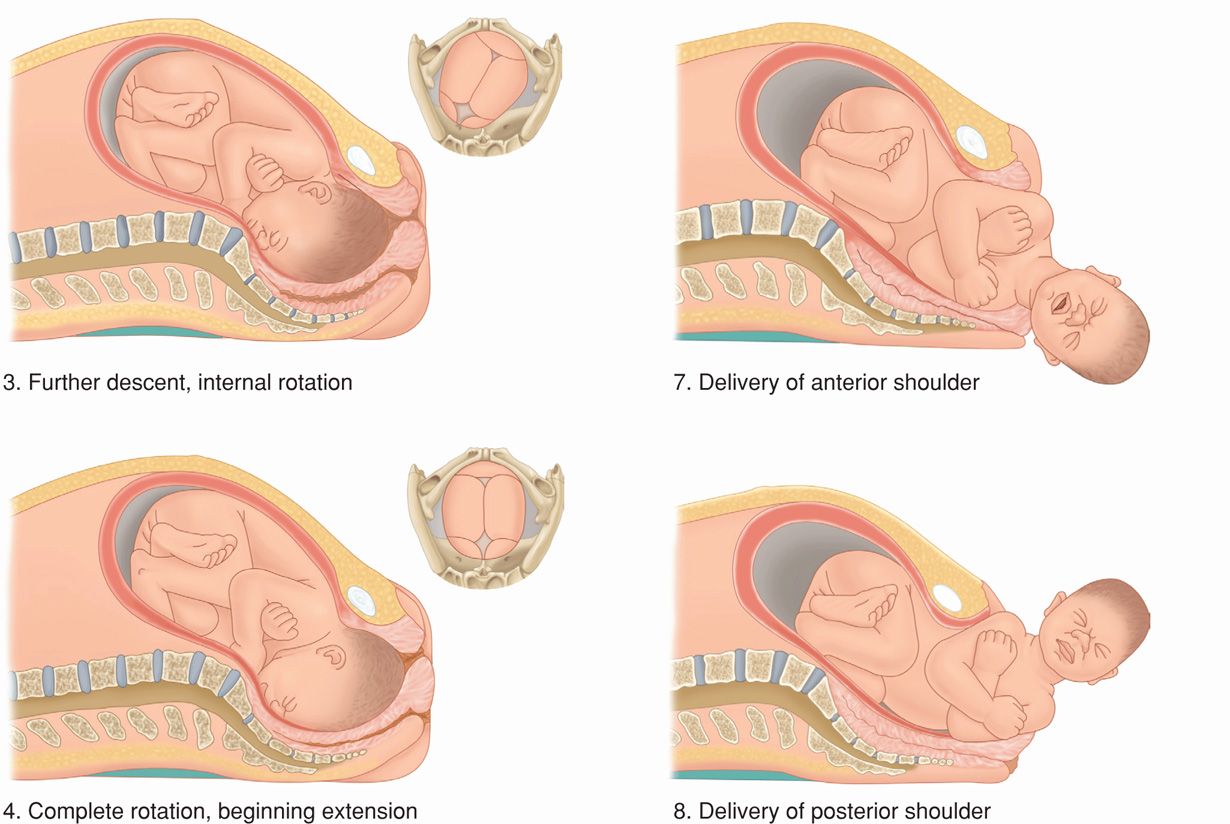

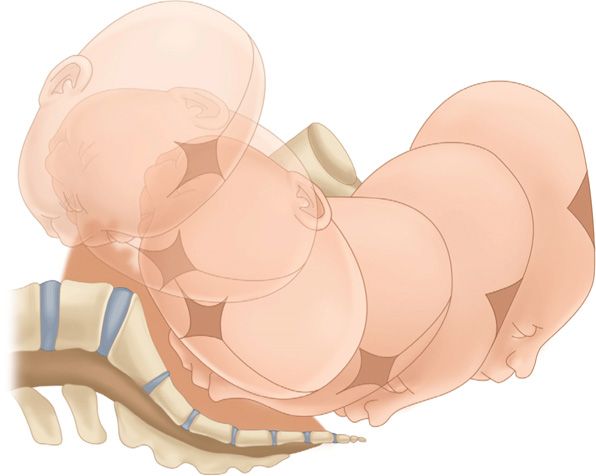

The positional changes of the presenting part required to navigate the pelvic canal constitute the mechanisms of labor. The cardinal movements of labor are engagement, descent, flexion, internal rotation, extension, external rotation, and expulsion (Fig. 22-11). During labor, these movements not only are sequential but also show great temporal overlap. For example, as part of engagement, there is both flexion and descent of the head. It is impossible for the movements to be completed unless the presenting part descends simultaneously. Concomitantly, uterine contractions effect important modifications in fetal attitude, or habitus, especially after the head has descended into the pelvis. These changes consist principally of fetal straightening, with loss of dorsal convexity and closer application of the extremities to the body. As a result, the fetal ovoid is transformed into a cylinder, with the smallest possible cross section typically passing through the birth canal.

Figure 22-11 Cardinal movements of labor and delivery from a left occiput anterior position.

Engagement

The mechanism by which the biparietal diameter—the greatest transverse diameter in an occiput presentation—passes through the pelvic inlet is designated engagement. The fetal head may engage during the last few weeks of pregnancy or not until after labor commencement. In many multiparous and some nulliparous women, the fetal head is freely movable above the pelvic inlet at labor onset. In this circumstance, the head is sometimes referred to as “floating.” A normal-sized head usually does not engage with its sagittal suture directed anteroposteriorly. Instead, the fetal head usually enters the pelvic inlet either transversely or obliquely. Segel and coworkers (2012) analyzed labor in 5341 nulliparous women and found that fetal head engagement before labor onset did not affect vaginal delivery rates in either spontaneous or induced labor.

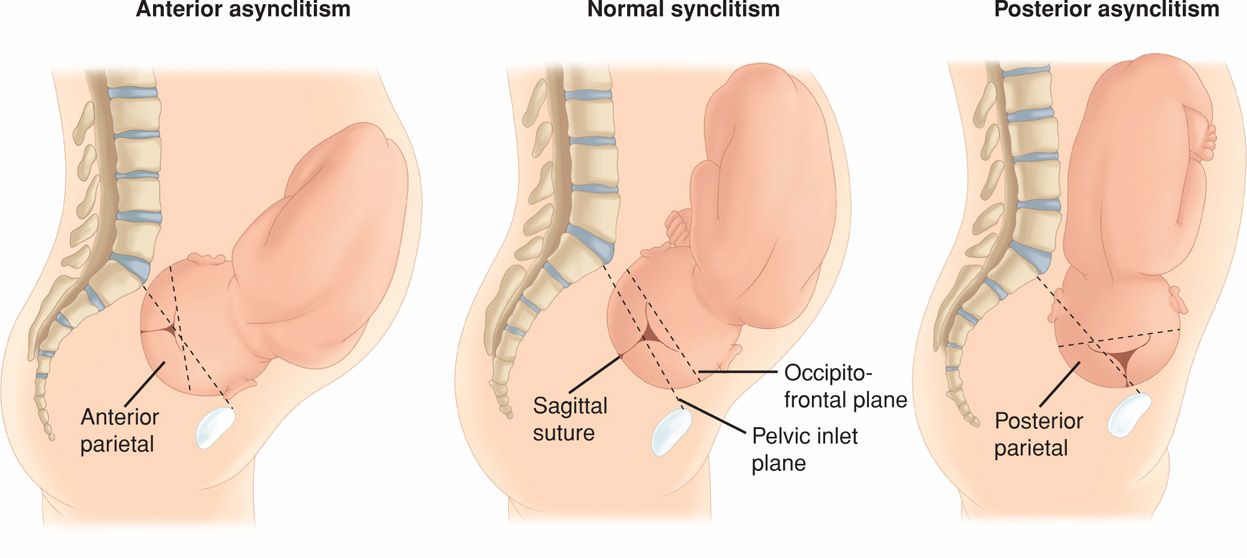

Asynclitism. The fetal head tends to accommodate to the transverse axis of the pelvic inlet, whereas the sagittal suture, while remaining parallel to that axis, may not lie exactly midway between the symphysis and the sacral promontory. The sagittal suture frequently is deflected either posteriorly toward the promontory or anteriorly toward the symphysis (Fig. 22-12). Such lateral deflection to a more anterior or posterior position in the pelvis is called asynclitism. If the sagittal suture approaches the sacral promontory, more of the anterior parietal bone presents itself to the examining fingers, and the condition is called anterior asynclitism. If, however, the sagittal suture lies close to the symphysis, more of the posterior parietal bone will present, and the condition is called posterior asynclitism. With extreme posterior asynclitism, the posterior ear may be easily palpated.

FIGURE 22-12 Synclitism and asynclitism.

Moderate degrees of asynclitism are the rule in normal labor. However, if severe, the condition is a common reason for cephalopelvic disproportion even with an otherwise normal-sized pelvis. Successive shifting from posterior to anterior asynclitism aids descent.

Descent

This movement is the first requisite for birth of the newborn. In nulliparas, engagement may take place before the onset of labor, and further descent may not follow until the onset of the second stage. In multiparas, descent usually begins with engagement. Descent is brought about by one or more of four forces: (1) pressure of the amnionic fluid, (2) direct pressure of the fundus upon the breech with contractions, (3) bearing-down efforts of maternal abdominal muscles, and (4) extension and straightening of the fetal body.

Flexion

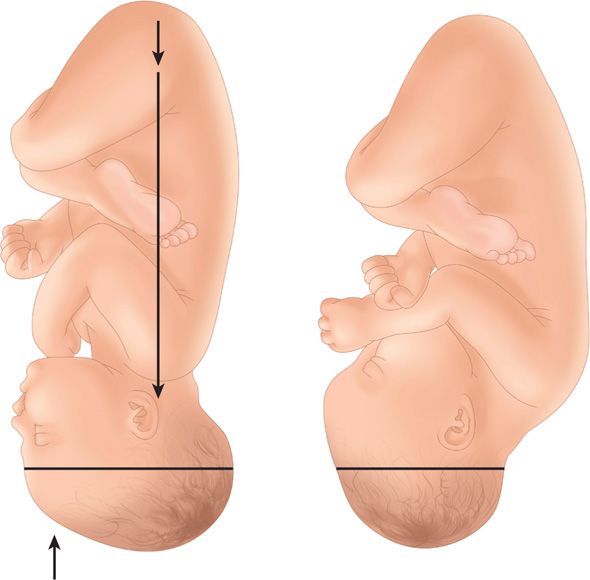

As soon as the descending head meets resistance, whether from the cervix, pelvic walls, or pelvic floor, it normally flexes. With this movement, the chin is brought into more intimate contact with the fetal thorax, and the appreciably shorter suboccipitobregmatic diameter is substituted for the longer occipitofrontal diameter (Figs. 22-13 and 22-14).

FIGURE 22-13 Lever action produces flexion of the head. Conversion from occipitofrontal to suboccipitobregmatic diameter typically reduces the anteroposterior diameter from nearly 12 to 9.5 cm.

FIGURE 22-14 Four degrees of head flexion. The solid line represents the occipitomental diameter, whereas the broken line connects the center of the anterior fontanel with the posterior fontanel. A. Flexion poor. B. Flexion moderate. C. Flexion advanced. D. Flexion complete. Note that with complete flexion, the chin is on the chest. The suboccipitobregmatic diameter, the shortest anteroposterior diameter of the fetal head, is passing through the pelvic inlet.

Internal Rotation

This movement consists of a turning of the head in such a manner that the occiput gradually moves toward the symphysis pubis anteriorly from its original position or, less commonly, posteriorly toward the hollow of the sacrum (Figs. 22-15 to 22-17). Internal rotation is essential for completion of labor, except when the fetus is unusually small.

FIGURE 22-15 Mechanism of labor for the left occiput transverse position, lateral view. A. Engagement. B. After engagement, further descent. C. Descent and initial internal rotation. D. Rotation and extension.

FIGURE 22-16 Mechanism of labor for left occiput anterior position.

FIGURE 22-17 Mechanism of labor for right occiput posterior position showing anterior rotation.

Calkins (1939) studied more than 5000 women in labor to ascertain the time of internal rotation. He concluded that in approximately two thirds, internal rotation is completed by the time the head reaches the pelvic floor; in about another fourth, internal rotation is completed shortly after the head reaches the pelvic floor; and in the remaining 5 percent, rotation does not take place. When the head fails to turn until reaching the pelvic floor, it typically rotates during the next one or two contractions in multiparas. In nulliparas, rotation usually occurs during the next three to five contractions.

Extension

After internal rotation, the sharply flexed head reaches the vulva and undergoes extension. If the sharply flexed head, on reaching the pelvic floor, did not extend but was driven farther downward, it would impinge on the posterior portion of the perineum and would eventually be forced through the perineal tissues. When the head presses on the pelvic floor, however, two forces come into play. The first force, exerted by the uterus, acts more posteriorly, and the second, supplied by the resistant pelvic floor and the symphysis, acts more anteriorly. The resultant vector is in the direction of the vulvar opening, thereby causing head extension. This brings the base of the occiput into direct contact with the inferior margin of the symphysis pubis (see Fig. 22-16).

With progressive distention of the perineum and vaginal opening, an increasingly larger portion of the occiput gradually appears. The head is born as the occiput, bregma, forehead, nose, mouth, and finally the chin pass successively over the anterior margin of the perineum (see Fig. 22-17). Immediately after its delivery, the head drops downward so that the chin lies over the maternal anus.

External Rotation

The delivered head next undergoes restitution (see Fig. 22-11). If the occiput was originally directed toward the left, it rotates toward the left ischial tuberosity. If it was originally directed toward the right, the occiput rotates to the right. Restitution of the head to the oblique position is followed by external rotation completion to the transverse position. This movement corresponds to rotation of the fetal body and serves to bring its bisacromial diameter into relation with the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet. Thus, one shoulder is anterior behind the symphysis and the other is posterior. This movement apparently is brought about by the same pelvic factors that produced internal rotation of the head.

Expulsion

Almost immediately after external rotation, the anterior shoulder appears under the symphysis pubis, and the perineum soon becomes distended by the posterior shoulder. After delivery of the shoulders, the rest of the body quickly passes.

Occiput Posterior Presentation

Occiput Posterior Presentation

In approximately 20 percent of labors, the fetus enters the pelvis in an occiput posterior (OP) position (Caldwell, 1934). The right occiput posterior (ROP) is slightly more common than the left (LOP). It appears likely from radiographic evidence that posterior positions are more often associated with a narrow forepelvis. They also are more commonly seen in association with anterior placentation (Gardberg, 1994a).

In most occiput posterior presentations, the mechanism of labor is identical to that observed in the transverse and anterior varieties, except that the occiput has to internally rotate to the symphysis pubis through 135 degrees, instead of 90 and 45 degrees, respectively (see Fig. 22-17).

Effective contractions, adequate head flexion, and average fetal size together permit most posteriorly positioned occiputs to rotate promptly as soon as they reach the pelvic floor, and labor is not lengthened appreciably. In perhaps 5 to 10 percent of cases, however, rotation may be incomplete or may not take place at all, especially if the fetus is large (Gardberg, 1994b). Poor contractions, faulty head flexion, or epidural analgesia, which diminishes abdominal muscular pushing and relaxes pelvic floor muscles, may predispose to incomplete rotation. If rotation is incomplete, transverse arrest may result. If no rotation toward the symphysis takes place, the occiput may remain in the direct occiput posterior position, a condition known as persistent occiput posterior. Both persistent occiput posterior and transverse arrest represent deviations from the normal mechanisms of labor and are considered further in Chapter 23.

Fetal Head Shape Changes

Fetal Head Shape Changes

Caput Succedaneum

In vertex presentations, labor forces alter fetal head shape. In prolonged labors before complete cervical dilatation, the portion of the fetal scalp immediately over the cervical os becomes edematous (Fig. 33-1, p. 647). This swelling, known as the caput succedaneum, is shown in Figures 22-18 and 22-19. It usually attains a thickness of only a few millimeters, but in prolonged labors it may be sufficiently extensive to prevent differentiation of the various sutures and fontanels. More commonly, the caput is formed when the head is in the lower portion of the birth canal and frequently only after the resistance of a rigid vaginal outlet is encountered. Because it develops over the most dependent area of the head, one may deduce the original fetal head position by noting the location of the caput succedaneum.

FIGURE 22-18 Formation of caput succedaneum and head molding.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree