Fig. 14.1

The different anatomic variants of EA/TEF

Type c (EA with distal TEF) is the commonest type making up to 86 % of the cases. This is followed by pure EA which forms about 8 %. The H-type TEF makes about 4–5 % of the cases.

Clinical Features

EA is usually detected shortly after birth and should be suspected in an infant with drooling (excessive salivation) that is frequently accompanied by choking, coughing, and sneezing.

The infant may become cyanotic and may stop breathing as the overflow of fluid from the blind pouch is aspirated into the trachea.

These patients should not be fed but when feeding is attempted the infant coughs, chokes, and becomes cyanotic.

Prompt recognition, appropriate clinical management to prevent aspiration, and urgent referral to an appropriate tertiary care center have resulted in a significant improvement in the rates of morbidity and mortality in these infants.

The presentation of those with H-type TEF is variable and nonspecific and a high index of suspicion is important in this regard.

Commonly, these patients present with recurrent chest infection, cyanosis, and choking during feeds.

Any newborn, infant, or child who presents with repeated attacks of choking and coughing during feeding, abdominal distension, and recurrent attacks of chest infection should raise suspicion of congenital H-type TEF and must be investigated accordingly.

In many of these patients, the diagnosis is difficult and occasionally delayed until late childhood or even up to adulthood.

Diagnosis

Prenatally, ultrasonographic findings of polyhydramnios, proximal dilated upper pouch, and a small or absent gastric bubble is suggestive but not confirmatory sign of isolated EA or EA and TEF as many other conditions are associated with polyhydramnios. This however must be confirmed postnatally.

The diagnosis can easily be confirmed by simply passing a nasogastric tube. Failure to pass the nasogastric tube and coiling of the tube in the upper pouch confirms the diagnosis of EA. A plain chest and abdominal x-ray will confirm this (Fig. 14.2).

Fig. 14.2

Chest x-ray showing an N/G coiled in the upper esophageal pouch. Note the gas in the stomach and intestines denoting an associated tracheoesophageal fistula in the first and absence of gas denoting an isolated esophageal atresia in the second

The presence of gas in the stomach and intestines with a coiled nasogastric tube in the proximal pouch confirms the diagnosis of EA with distal TEF. The level of nasogastric tube in relation to the vertebra can be used to determine the height of the upper pouch. This is important to plan the surgical repair (Fig. 14.2b).

The use of contrast esophagogram to confirm the diagnosis should be abandoned as this will not only delay their transfers but also increase the risk of hypothermia and aspiration pneumonia (Figs. 14.3 and 14.4).

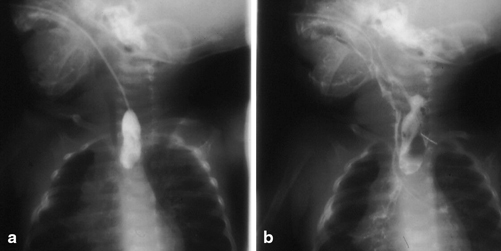

Fig. 14.3

a and b Chest x-rays showing esophageal atresia and aspiration pneumonia

Fig. 14.4

Upper pouch esophagogram showing esophageal atresia (a). Note the spillage of contrast into the tracheobronchial tree (b)

An echocardiogram is important to establish associated cardiac anomalies and a normal left-sided aortic arch.

Contrast-enhanced studies are necessary to identify or locate an H-type TEF (Fig. 14.5).

Fig. 14.5

a and b Esophagogram showing H-type tracheoesophageal fistula (arrows)

This requires an experienced radiologist who should perform contrast-enhanced studies (pull out esophagogram) with fluoroscopic control.

The study may have to be performed more than once to establish the diagnosis. Endoscopy and/or bronchoscopy may be performed to locate or rule out H-type TEF.

Associated Anomalies

Associated anomalies are frequent with EA, occurring in more than 50 % of patients (Table 14.1) .

Table 14.1

Associated anomalies in esophageal atresia

System

Potential anomalies

%

Cardiovascular

Ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, Fallot tetralogy, right-sided aortic arch, atrial septal defect, coarctation of the aorta

30–35

Musculoskeletal

Multiple or single hemi vertebrae, scoliosis, rib deformities, radial dysplasia, absent radius, radial-ray deformities, syndactyly, polydactyly, lower-limb tibial deformities

10–15

Gastrointestinal

Imperforate anus, duodenal atresia, malrotation, intestinal malformations, Meckel’s diverticulum, annular pancreas

14–20

Genitourinary

Renal agenesis or dysplasia, horseshoe kidney, polycystic kidney, ureteral and urethral malformations, hypospadias, undescended testicles

14–20

Chromosomal abnormalities

Trisomies 13, 21, or 18

4–5

Multiple

VATER/VACTERL

10

Most infants have more than one malformation. Infants with isolated EA have a higher incidence of other malformations than EA with TEF while the associated anomalies are less often in those with pure H-type TEF.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree