A key requirement in diagnosing female sexual dysfunction is that it creates personal distress for the woman, and many studies do not consider this nor do

they include women who are not in sexual relationships. One exception is the largest U.S. study of female sexual dysfunction, the Prevalence of Female Sexual Problems Associated with Distress and Determinants of Treatment Seeking survey (PRESIDE) that included over 30,000 women who responded to validated questionnaires and it included women who were not currently in a sexual relationship.

19 This study found that with or without personal distress, 43% of women reported at least one problem with sexual desire, arousal, or problems with orgasm. However, when asked about personal distress associated with the condition(s), only 22% of women reported personal distress and 12% attributed the distress to a specific type of sexual problem. Low levels of sexual desire was the most common sexual problem in respondents (39%), with orgasm difficulties only slightly less prevalent (21%); both were associated with distress in 5% of women.

19 The survey found that a poor self-assessment of health significantly correlated with distressing sexual problems for the participants.

The Challenge of Treatment

Female sexual disorders are often challenging to treat— even for practitioners specialized in the treatment of sexual dysfunction. Few medications exist that help to alleviate sexual dysfunctions, which can be frustrating for physicians as well as patients. In contrast, there are many medications that can interfere with sexual functioning. For example, approximately 30 million people are taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and it is estimated that about half of them experience alterations in their sexual behavior. Further, it is estimated that approximately half of this group will have persistent sexual issues even after they discontinue the medication.

22 Nonetheless, sexuality—including the lack of it—plays a profound role in many people’s experience of life and their relationships.

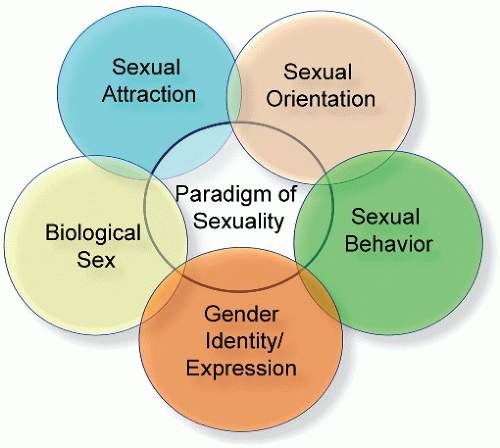

For many women, the three major determinants of sexual dysfunction include relationship factors, medical issues, and life phases. Relationship factors, such as stress, financial issues, communication issues, etc., all impact sexuality. Physiologic issues or medical conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, cancer, or medication side effects, to name a few, need to be considered as well. Mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety, and often, the medications used to treat them may create or significantly contribute to sexual problems. Life phases that affect sexual functioning include pregnancy, child rearing, and menopause. These three general areas do not occur in a vacuum, which is why a biopsychosocial treatment model is imperative. “The biopsychosocial model provides a compelling reason for skepticism that any single intervention (i.e., a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, supraphysiological doses of a hormone, processing of childhood victimization, marital therapy, pharmacotherapy of depression) will be sufficient for most patients or couples experiencing sexual dysfunction.”

23Many of the ways people cope and relieve stress have a negative impact on their sexual functioning, such as the following:

Overreliance on substances including food, nicotine, and alcohol

Overreliance on sedentary activity

Avoidance of deeper emotions which include depression, anger, and passion

Avoidance of vulnerability, maintaining tight control of mind and body

Use of biopsychosocial treatment approaches can help providers in their counseling of patients. These include sympathy and efforts to “normalize” the woman’s concerns by letting her know how common sexual problems are. General health issues such as nutrition, exercise, sleep, and chemical dependence are always an aspect of sexual dysfunction treatment. Psychosocial issues such as mood and stress must be addressed because they are a huge contributing factor to any woman’s sexual experience. The involvement of mental health professionals with expertise in sexuality and/or sex therapy is often helpful as well (

Table 9.4).

Other more concrete steps include the recommendation of books specific to the woman’s concerns (individual recommendations are offered in an appendix to this chapter), encouraging her focus on enjoyment of the process of making love versus the goal of penile-vaginal intercourse or orgasm, and encouraging novel sexual activities both partners are willing to participate in as well as doing new activities with their partners as a means of sparking renewed interest in each other.

Similar to what is seen in men, female sexual dysfunction is related to the same risk factors as cardiovascular disease: smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and endothelial damage.

24 Women with hypertension may have decreased lubrication, orgasm, and increased sexual pain, whether the hypertension is treated or not; unfortunately, some antihypertensive drugs used for treatment may induce sexual dysfunctions in women as well.

25 Although studies are not consistent, there is some evidence that diabetes may also significantly impact the sexual health of women through neuropathy, endocrine changes, and vascular compromise.

26,27Depression, anxiety, and psychotic disorders are recognized risk factors for sexual disorders even without treatment.

28,29 Treatment for these conditions may exacerbate or induce sexual dysfunction, particularly antidepressants, which may cause low libido and difficulty with orgasm. Benzodiazepines, antipsychotic medications, and atypical antipsychotic medications may impact sexual function adversely.

Sexual complaints are common during the postpartum period although there is no evidence of long-term differences in sexual dysfunction between women who delivered vaginally and those who had a cesarean section.

30 There is no evidence that parous women have more sexual dysfunction than nonparous women.

19Pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence are associated with sexual health issues, with 26 to 47% of women with urinary incontinence reporting sexual dysfunction.

31 In some reports, 11 to 45% of women experience urinary incontinence during intercourse, often with penetration or orgasm.

32,33 It is not surprising then, that in the PRESIDE study, urinary incontinence significantly correlated with distressing sexual problems.

19 The impact of surgical repair of pelvic floor disorders and sexual functioning is mixed, with some women reporting improvement and others reporting no change or new onset dyspareunia.

34,35In discussing sexual concerns with a woman, it is important to note any and all medications she may be taking; in some instances, it may be necessary to adjust or even change medication regimens to reduce sexual side effects—particularly antidepressants—because they are such a common contributor to sexual dysfunction. Other common medications that may interfere with sexual function include antihistamines, cardiovascular agents, antihypertensives, anxiolytics, and chemotherapy. Antihypertensives including thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors may interfere with normal vasocongestion of the genitals; out of these, thiazides are the most commonly implicated.

36 Anticholinergic drugs may decrease vaginal lubrication, whereas SSRIs may lead to diminished desire and problems with orgasm.

Progestin-only contraceptives do not appear to be associated with sexual dysfunction, whereas the effect of combined hormonal contraceptives on sexual health is controversial.

37 Although combined hormonal contraception suppresses testosterone levels through pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion, suppression, and an increase in sex hormone binding globulin, the correlation between this decrease in androgen activity and the sexual function of women using combined hormonal contraception is not clear cut. In fact, the use of exogenous androgens in oral contraceptive users does not appear to improve desire.

Substance use/abuse may also impede normal sexual functioning; alcohol is the most common agent. Other substances such as marijuana, cocaine, and heroine may also result in sexual dysfunction.

In order to establish the diagnosis of female sexual dysfunction, the sexual problem must not only be recurrent or persistent, it must also cause personal distress or interpersonal difficulty.

18 Sexual dysfunctions are categorized by the specific phase of the sexual response cycle they occur in, although in practice, many of the disorders are not limited to just one phase and more than one disorder may occur within the same patient. Because many of the female sexual dysfunctions will overlap, it is important to determine the primary disorder, that is, ask the patient what she believes is her primary sexual concern, and then note how any comorbid dysfunctions developed over time. For example, a patient may be concerned about her lack of desire to have sex, but further history taking reveals that she began to develop pain during sex and subsequently, her desire for it declined. In this instance, dyspareunia is the most likely primary dysfunction.

The American Psychiatric Association classification of female sexual disorders has six categories:

When speaking with a woman who may have sexual dysfunction, it is clear that a complete medical and medication history must be obtained. The sexual history should include current sexual health problems, the nature of the problems, whether it is she or her partner who is having problems (or both), and whether they cause the patient any personal distress or interpersonal problems. Although a pelvic examination is strongly

recommended for patients with sexual pain, it should also be performed in patients with other sexual health complaints as well to confirm normal anatomy; evaluate for tenderness, masses, or lesions; look for prolapse or atrophy; and evaluate any concomitant gynecologic complaints that may, or may not, be related to the sexual dysfunction (

Table 9.5).

Depending on the results of the history taking and/or physical examination, further laboratory testing may be warranted, for example, pelvic ultrasound, cervical cultures, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), complete blood count (CBC), or prolactin levels. Androgen levels should not be measured as a means of determining the cause of a sexual problem because they are not an independent predictor of sexual function in women and the available assays for serum androgen levels in women are unreliable. The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline supports this approach and does not recommend diagnosing androgen deficiency in women because there is no well-defined clinical syndrome associated with this diagnosis, and there are no age-based normative data for serum testosterone and free testosterone concentrations in women.

38 Testing for estradiol or other estrogen levels or other sex steroids has no use in evaluating sexual complaints.

Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder

While acknowledging that there is no consensus about what is “normal” desire and that each woman will have her own definition based on her culture, background, sexual experience(s), and her own biologic drive, hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) is the most common sexual dysfunction among women, with a prevalence rate of approximately 22%.1 HSDD is currently defined in the

DSM-5 as persistently or recurrently deficient (or absent) sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity.

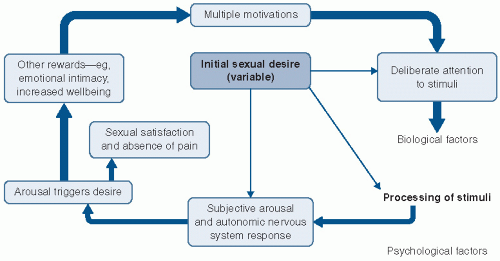

18 Criticisms of this definition note that it considers sexual thoughts or fantasies to be a primary trigger for sexual behavior, but for women, the desire for sexual activity may be prompted by factors not addressed in the current definition, for example, wanting to experience tenderness, appreciation, or the feeling of desirability. Furthermore, the lack of sexual desire at the start of a sexual encounter does not necessarily indicate HSDD because some women may not feel a desire for sex initially but with sexual stimulation develop the desire. HSDD can be subdivided into a general lack of sexual desire or a situational one where the woman lacks desire for her current partner but still has desire for sexual stimulation either alone or with someone else. HSDD may be acquired, that is, it starts after a period of normal sexual function or it may be lifelong— the woman had always had low or no sexual desire.

The third International Consultation on Sexual Medicine (ICSM) recommended refining HSDD to directly reflect the fact that absence of desire in a woman does not necessarily equate with dysfunction.

39 It has been suggested that a lack of female desire is “inevitable” in long-term relationships and even in those partnerships considered healthy.

40,41 Research does demonstrate that women with low desire are frequently happy with their romantic relationship and not distressed about their low libido.

42 When the criteria of personal distress is taken into account, the prevalence of HSDD drops by about half.

43 It is possible that the lack of distress in some of these women is because they feel their situation is hopeless and they have essentially “given up” on their sex lives. It is not known if these women would admit distress if they believed their situation was able to be improved and they could feel sexual excitement again.

Because of its complex etiology, HSDD is perhaps the most difficult sexual concern to treat. Common concerns

expressed by a woman with low desire include loss of pleasure in feeling feminine, a loss of physical and emotional intimacy with her partner, fear of her partner’s infidelity, feelings of disconnection from her body, and feeling detached from sensual physical sensations. Many dynamics contribute to low desire in women, including physical, hormonal, emotional, spiritual, and partner variables (

Table 9.6).

From a physical perspective, medications—such as antidepressants, oral contraceptives, antihistamines, antihypertensives, and diuretics—can negatively impact libido for some women. A woman who is tired and overworked may lose her interest in sex. A woman’s disconnection from her physical self is an additional variable. In a fastpaced culture, people spend most of their time thinking rather than feeling. Tuning into sexual desire requires tuning into the body more generally and learning to feel pleasure in the body more generally as well. Lifestyle issues, such as poor sleep or inadequate nutrition, are also potential culprits. Emotions such as depression, anxiety, and stress are additional factors in HSDD.

43 Poor body image may cause diminished desire. When evaluating women with HSDD, interpersonal issues often need to be addressed as well. If a woman’s lover is unskilled, or if her partner is a man with erectile dysfunction (ED) or premature ejaculation, or if the woman believes her sex life is rote and boring, a woman may lose her desire for sex. These issues are troubling for many women who do not want to hurt a partner’s feelings with negative feedback about their sexual skills. Relationship conflicts and power struggles can also significantly weaken a woman’s receptivity to sex. Relatedly, if she feels a spiritual void with her partner, she may be reluctant to open up to him sexually.

Regardless of how or why a woman’s sex drive initially declines, both her mind and her body tend to be impacted over time. The Women’s International Study of Health and Sexuality (WISHeS) study found that women with HSDD had large and statistically significant declines in health status, particularly in mental health, social functioning, vitality, and emotional role fulfillment.

44 Others have found that women with HSDD have more comorbid medical conditions and are twice as likely to report fatigue, depression, issues with memory, back pain, and a lower quality of life.

45A woman’s medical conditions may influence her risk for HSDD, but assuming that a biomedical approach alone will best serve the patient for treatment purposes is not recommended. The biopsychosocial treatment model includes biological, psychological, and social/interpersonal components in its approach and places less pressure on the physician to offer a single solution to such a complex problem. It is imperative that a woman expects to play a significant role in her own treatment rather than waiting for her physician to “heal” her because the patient will probably be disappointed by the latter option. “It is up to the patient to take the risks involved in deepening her sense of connection to her own body and to her partner. The patient must be willing to experiment with her sensual expression, open to feelings of joy and vulnerability with her partner, and let go of control to her partner. She must get adequate sleep and proper nutrition for her body to respond sexually.”

46 Thus, HSDD treatment involves a cooperative effort between physician and patient. Many clinicians believe they do not have the tools or the skills to screen or assess patients for HSDD. There are several screening tools available that are easy to use. One example is the Decreased Sexual Desire Screener (DSDS) that is done with the patient. It starts with four questions and if the patient answers “yes” to all of the questions, they continue to the fifth question that has seven parts

(

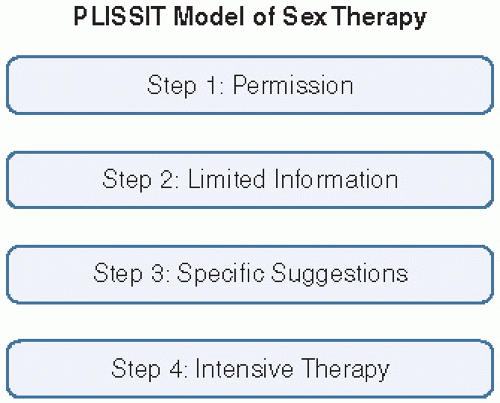

Table 9.7). If the patient is identified as having HSDD, the clinician may choose to employ the PLISSIT model (

Fig. 9.3). This model has four steps: permission, limited information, specific suggestions, and intensive therapy. The first step validates the patient’s concerns and makes clear that sexual problems such as HSDD are real and very prevalent. The second step provides basic education to the patient about the sexual response cycle, the components of desire, and possible resources and tools that further discuss the patient’s sexual concerns. In the third step, the clinician may offer suggestions to help improve her desire levels. The final step is often beyond the scope of most clinician’s expertise and involves referral to a specialist in sexual medicine. Sex therapy is brief cognitive behavioral psychotherapy that specifically focuses on sexual concerns; it tends to be short term (5 to 20 visits) and is solution focused. In some instances, referral to a mental health specialist to address other issues or concerns not specifically related to sex may also be helpful for the patient.

There are no FDA-approved pharmacologic treatments for women’s sexual dysfunction at this writing. Nonetheless, some women find benefit from testosterone supplementation in the treatment of low desire.

47 Challenges to the use of testosterone therapy involve the fact that testosterone assays in this country are male-based and not sensitive enough for women who occupy the lower 10% of those levels. Obviously, it is also challenging to use supplementation intended for men on females. Practitioners are thus forced to use off-label or compounded products, often as an empiric trial after ruling out other causes for low desire. Off-label treatment with testosterone supplementation is controversial, particularly for premenopausal patients. There is a lack of agreement regarding normative ranges for women, as well as no standard formulation for systemic androgen replacement.

48,49 Some practitioners, as well as the Endocrine Society, do not recommend testosterone therapy because of the lack of diagnostic levels indicating testosterone insufficiency and the lack of long-term safety data,

50 especially with respect to heart disease and breast cancer. Studies have shown mixed results with regards to testosterone in vivo decreasing or increasing breast cell proliferation.

51,52 In one study, testosterone in vitro was shown to decrease breast cell proliferation.

53 However, many questions remain, for example, does testosterone directly improve libido or is it aromatization to estrogen, and does testosterone work on sex drive directly or indirectly via mood?

Conservative guidelines for practitioners who administer off-label testosterone therapy have made some general, conservative recommendations during testosterone use. For example, according to Basson et al.,

54

… the testosterone patch appears to be effective in the short term in postmenopausal women with

HSDD. Achieving physiological testosterone levels by transdermal delivery minimizes adverse effects. Relative contraindications include androgenic alopecia, acne, hirsutism hyperlipidemia, and liver dysfunction. Absolute contraindications include presence or high risk breast cancer, endometrial cancer, venothrombotic episodes, cardiovascular disease. Monitoring should include annual breast and pelvic examinations, annual mammography, evaluation of abnormal bleeding, evaluation for acne, hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia. Monitor testosterone by mass spectrometry (sex hormone binding globulin, calculated free T) with goal of not exceeding normal values. Consider lipid profile, liver function tests, complete blood count. Use for more than 6 months is contingent on clear improvement and absence of adverse effects.

Any discussion about the use of androgen therapy, in any form, must include a full explanation of all potential benefits and risks. Women considering androgen therapy must understand that the data on safety and efficacy is very limited, and this includes data on long-term use, either with or without estrogen therapy (ET). They should also be aware that none of the commonly used androgen therapies are approved by the FDA for treating HSDD because of the limited clinical trial data as well as the concerns about long-term safety. This discussion should be carefully documented in the patient’s records.

Testosterone is the most commonly used androgen treatment for female sexual dysfunction, particularly HSDD. In randomized trials and systematic reviews where it was used with estrogen (with or without progestin)—it has been in postmenopausal women—it did show an improvement in sexual function.

55,

56,

57,

58 The formulations and delivery methods vary across studies, although the largest series of controlled clinical trials used a transdermal testosterone patch that delivered 300 mcg/day of testosterone in postmenopausal women with HSDD.

56,58 Most of the studies included postmenopausal women who were on concurrent ET, although one large trial found similar results in women not using estrogen/progestin treatment.

59 Data on the use of androgen treatment in premenopausal women are scant and inconclusive, and the inadvertent exposure of a developing fetus is a significant potential risk to be considered.

60,61In Europe, the Intrinsa 300 mcg testosterone patch is approved for use in female sexual dysfunction; it is applied twice weekly. Despite the lack of FDA-approved androgen therapies in the United States, products that are used include methyltestosterone, compounded micronized testosterone, compounded testosterone ointments or creams (1 or 2%, use 0.5 g every day applied to the skin on the arms, legs, or abdomen), and testosterone patches or gels formulated for hypogonadal men. Cutting patches is not advised because there is no data available on product stability or the resulting testosterone levels. Gels are difficult to use because the amount needed would be approximately 1/10th the dose prescribed for men, and this is very hard to accurately gauge with gels in pumps or packets. There have been FDA reports of adverse events due to secondary exposure of children to the skin of adults who recently applied topical testosterone. Use of oral formulations may result in adverse changes in liver enzymes or lipid levels because of the first-pass hepatic metabolism.

Flibanserin is a 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)1A agonist and 5-HT2A antagonist, which reduces the inhibitory effect of serotonin on dopamine and norepinephrine. It is a nonhormonal, centrally acting agent, which went before FDA review after completion of its phase III clinical trials in 2010, but it was not approved, in large part because the absence of long-term treatment data made it difficult to evaluate effectively.

Although there was hope initially that phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil would be beneficial in women with female sexual dysfunction, studies reported inconsistent results.

62,

63,

64 There is some evidence that sildenafil may have good results on sexual arousal and orgasm in premenopausal women with SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction.

65 However, there was no change in sexual desire for women in this study.

There is some evidence that bupropion, 150 mg twice a day or sustained release 300 mg/day, may increase sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm compared to placebo, but more trials are clearly needed.

66,67