ISSVD 1976

ISSVD 1986

WHO 1994

ISSVD 2004

LASTa 2012

WHO 2014

Hyperplastic dystrophy with atypia, mild

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) I

Mild dysplasia (VIN 1)

–

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL)

LSIL

Hyperplastic dystrophy with atypia, moderate

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) II

Moderate dysplasia (VIN 2)

VIN, usual type (uVIN)

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL)

HSIL

Hyperplastic dystrophy with atypia, severe

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) III or VIN III, differentiated type

Severe dysplasia (VIN 3)

VIN, usual type (uVIN) or VIN, differentiated type (dVIN)

HSIL or differentiated-type VIN

Squamous carcinoma in situ (CIS)

CIS or CIS, differentiated type

The earliest description of intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva was published in France in 1922 [1]. As these lesions were increasingly recognized, they came to be known as “Bowen disease” due to their similarity to lesions described in the nonvulvar skin first described by Bowen in 1912 [2]. Similar terms such as “Bowen dermatosis” [3] were also used in reference to vulvar intraepithelial disease in the earliest pathologic literature. By the 1950s, terms such as “intraepithelial carcinoma” [4]) and “carcinoma in situ” [5], thought to better represent the biology of the lesions, were added to the repertoire. The first recognition that there seemed to be more than one type of intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva came in 1961, with the publication of two seminal papers by Abell and Gosling [6, 7] in which they described both a more common “Bowen’s type” and a less common “simplex” type of intraepithelial carcinoma. By the 1970s, all of these terms, in addition to a variety of other clinically derived terms such as “erythroplasia of Queyrat,” “leukoplakia,” “leukoplakic vulvitis,” and “bowenoid papulosis,” were all being used to describe intraepithelial lesions of the vulva. It was, at the same time, becoming increasingly clear that not all of these lesions exhibited the same biologic behavior.

By this time, it was also becoming evident that intraepithelial lesions of the vulva, as of the cervix, consisted of both full-thickness lesions with severe nuclear atypia and high proliferation and of lesser degrees of intraepithelial changes. In 1976, the ISSVD published the first of several reports on the nomenclature of vulvar diseases [8], with the intent to establish a more uniform and clinically relevant terminology. The report introduced the term “squamous carcinoma in situ” to refer to the most severe lesions with severe, full-thickness cellular abnormalities and classified less severe abnormalities under the heading of “hyperplastic dystrophy with atypia,” which were subdivided into mild, moderate, and severe categories.

Around the same time the ISSVD made this first attempt to standardize the diagnostic terminology of vulvar lesions, major advances were beginning in the understanding of cervical disease which would come to impact the understanding of vulvar disease. In the cervix, squamous lesions had long been categorized as either dysplasias, which were not considered malignant, or carcinoma in situ, which was malignant by definition. But during the 1960s, it became increasingly evident that carcinoma in situ was not, in fact, a distinct histopathologic and biologic entity. In 1973, Richart introduced a new terminology for cervical intraepithelial disease which eliminated the term. The precursors of cervical carcinoma, he argued, were better understood as a single disease process evolving through a spectrum of morphologic changes that he termed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) [9]. In 1982, Crum and Richart introduced the term “vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia” (VIN) for description of vulvar squamous lesions, reflecting the growing understanding that these lesions were pathogenetically similar to those of the cervix [10, 11]. The term was accepted by the ISSVD in 1986 [12] when it recommended that that term be used for all squamous intraepithelial lesions of the vulva, with lesions subcategorized into three tiers of severity, designated VIN I, VIN II, and VIN III. To incorporate those relatively uncommon vulvar intraepithelial lesions previously referred to predominantly as the “simplex” type, a subcategory termed VIN III, differentiated type, was included. This differentiated VIN lesion did not have a counterpart in the cervix.

For the next 18 years, aside from a revision in 1989 recommending the replacement of the roman numerals with Arabic ones [13], the ISSVD nomenclature remained stable; however, competing systems of nomenclature were introduced. In 1994, the World Health Organization (WHO), in the second edition of “Histologic Typing of Female Genital Tract Tumors” [14], addressing the issue of inconsistent terminology for vulvar lesions, accepted VIN 1–3 as an acceptable alternative for three of the four tiers in its preferred terminology of dysplasia/carcinoma in situ for intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. In this system, lesions were categorized as mild dysplasia (VIN 1), moderate dysplasia (VIN 2), severe dysplasia (VIN 3), and carcinoma in situ, the latter of which included a subset of “carcinoma in situ, simplex type.” This publication also introduced the overarching term “squamous intraepithelial lesion” into the mix as a general term to cover all of the described subcategories with the exception of “carcinoma in situ, simplex type.”

Up to this point, the evolution of nomenclature for intraepithelial neoplasia closely mirrored that of the uterine cervix. The majority of intraepithelial lesions of the vulva showed a morphology similar to those of the cervix, and especially as it became clear that lesions in both sites were strongly associated with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV), the carcinogenicity of which was becoming increasingly well understood, it was tempting to try to fit vulvar lesions into that new paradigm.

While there were certainly many important similarities between intraepithelial neoplasias of the vulva and cervix, significant differences prevented consideration of the two as completely analogous. To begin with, there was the mysterious entity of the “differentiated” or “simplex” lesions, which did not have a morphologic counterpart in the cervix and showed little association with HPV, suggesting an alternative etiology must exist for them. There was also the unexplained difference in the low-grade lesions of these different sites, with low-risk HPV-type-related exophytic condylomata appearing commonly on the vulva but rarely in the cervix, while flat low-grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasias were common on the cervix but rare on the vulva. By far the most significant and troubling issue, however, was that as research into the association of HPV with cervical and vulvar disease progressed, the association in vulvar lesions proved considerably weaker than that in the cervix. While almost all CIN 2 and 3 lesions, as well as associated cervical squamous carcinomas and even a significant portion of CIN 1, consistently demonstrated the presence of high-risk HPV viral subtypes [15–17], the findings in vulvar lesions were less consistent. Studies reported a wide range, from 53 % to 92 % [18–21], of VIN 2 and 3 lesions to contain high-risk HPV viral DNA, but the average HPV positivity rate was considerably lower than in the cervix. What was even more troublesome was that significantly fewer vulvar squamous cell carcinomas than VIN cases were HPV positive, with studies finding anywhere from 0 to 48 % [18, 21–26] and averaging on the lower side of this range.

The perplexing failure of oncogenic HPV to explain vulvar intraepithelial squamous lesions as well as it did for cervical intraepithelial lesions led some investigators to look more closely at vulvar cancers and their associated precursors. In so doing, it became evident that there was, in fact, a significant difference in morphology between HPV-positive and HPV-negative tumors, as there was for their associated intraepithelial lesions. HPV-negative tumors tended to be well-differentiated, keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas [19, 22, 23] and to be associated with adjacent non-neoplastic vulvar dermatoses like squamous hyperplasia or lichen sclerosus [27, 28], or the differentiated type of VIN as an associated intraepithelial component [28]. HPV-positive tumors tended to show a warty or basaloid pattern and to have associated VIN 3 with similar morphology in a large percentage of cases [18, 19, 22, 23, 25, 29]. Epidemiologic data also showed significant differences between women with HPV-positive tumors and those with HPV-negative ones, with the former presenting about 20 years earlier [22, 23, 29] and more often also affected by other HPV-related disease of the cervix, vagina, or vulva [20, 27, 30–32]. The evidence was building that squamous carcinoma of the vulva was less homogeneous than that of the cervix. Taken together, the morphologic, virologic, and epidemiologic data suggested that, unlike in the uterine cervix, there was not just one pathway to squamous carcinoma of the vulva, but two, with two distinct intraepithelial precursor lesions, only one of which was related to HPV [23, 25, 33], as summarized in Table 9.2.

Table 9.2

The two pathways to squamous carcinoma of the vulva

HPV-related squamous carcinoma of the vulva | Non-HPV-related squamous carcinoma of the vulva | |

|---|---|---|

Patient age | Younger (40s–50s) | Older (60s–70s) |

Associated diagnoses | Other HPV-related lesions of the lower anogenital tract (condyloma, cervical, vaginal and/or anal intraepithelial neoplasias) | Non-neoplastic dermatoses (lichen sclerosus, squamous hyperplasia, etc.) |

Associated in situ lesion | uVIN | dVIN |

Tumor morphology | Warty and/or basaloid | Well-differentiated keratinizing |

By this time, advances in the understanding of HPV pathogenesis in the cervix had led to further change in how cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions were viewed. The biologic evidence supported the existence of only two, rather than three, types of lesions. Thus began a shift, first in the reporting of cervical cytology specimens and subsequently in reporting tissue biopsies, to the classification of lesions into either “low-grade” (CIN 1) or “high-grade” (CIN 2–3) categories. This shift was justified not only on the grounds that it better reflected the biologic evidence, but also that it allowed for more reproducible diagnosis [34, 35] and was more practical, given that most clinicians already treated CIN 2 and CIN 3 lesions the same way.

The evolving understanding of how HPV influenced the development of cervical cancer , and that there were both HPV-dependent and non-HPV-dependent pathways to vulvar carcinoma , led to yet another revision in terminology for vulvar disease. In 2003, the WHO revised its terminology to favor the use of VIN over the synonyms of dysplasia and carcinoma in situ, defining both warty and basaloid types associated with HPV, which were further classified into VIN 1, 2, and 3, and maintaining the previous terminology of “carcinoma in situ, simplex type” for lesions with a differentiated morphology [36]. In 2004, the ISSVD undertook more drastic revisions, abandoning the category of VIN 1 altogether and combining VIN 2 and 3 into one category of simply “VIN” [37, 38]. In this system, VIN is subclassified into two categories, the usual type, abbreviated “uVIN,” and the differentiated type, abbreviated “dVIN,” and uVIN is further subclassifiable as warty, basaloid, or warty/basaloid if desired. The decision to abolish the category of VIN 1 has been controversial, but the justifications given were that the diagnosis is rare without an accompanying higher-grade lesion [39], that it is poorly reproducible [34, 40], and that, unlike in the cervix, evidence is lacking that it may progress to a higher-grade lesion [37, 41]. The same arguments which had been used to support the combination of CIN 2 and 3 into one category of “high-grade” lesions were found to be applicable to VIN 2 and VIN 3 [34, 39], at least the HPV-related types, and ultimately to all HPV-related lesions of the lower anogenital tract. It is for this reason that a recent proposal has been made to standardize the nomenclature for all HPV-related lesions of the lower anogenital tract ; the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization Project (LAST) proposes that a two-tier system of LSIL and HSIL be used to refer to all HPV-related squamous intraepithelial lesions of the vulva, vagina, cervix, anus, perianal area, and penis [42], rather than the organ-specific intraepithelial neoplasia nomenclatures, with the option to maintain that specific nomenclature in parentheses; thus, lesions formerly categorized as VIN 2 or 3 or uVIN in ISSVD terminology would be designated HSIL (VIN 2–3). This system pertains only to HPV-related lesions, so it makes no recommendation as to terminology for differentiated lesions of the vulva. Most recently, the WHO has adopted identical terminology, retaining the term “differentiated-type VIN” for those lesions not related to HPV [43].

As is evident from the terminology used and from their earliest descriptions, intraepithelial lesions have always been recognized as preinvasive lesions. This understanding was based initially on morphologic grounds, and later supported by the observation that these lesions were observed adjacent to invasive disease in 7–25 % of cases examined [4, 7, 44], and further supported by the observation that when followed over time a significant proportion of patients with these lesions developed squamous carcinoma [6, 44]. These observations continued to be made over the ensuing decades, and the strength of the association of VIN with carcinoma has even increased over time, as more attention has been paid to vulvar disease and interventions have been initiated earlier in the disease process, with later studies reporting the presence of intraepithelial disease adjacent to vulvar carcinoma in 20–100 % of cases [18, 27, 45–54]. This strong association remains compelling evidence that VIN is a precancerous lesion. But association does not prove causation, as the association of squamous hyperplasia, lichen sclerosis, and other non-neoplastic vulvar dermatoses with vulvar carcinoma has been noted to be as strong, if not stronger than that of VIN. It has not been until relatively recently that the underlying biology of VIN has begun to come to light, and there is a tremendous amount still to discover, but these investigations have continued to provide additional support to the long-held understanding of VIN as a precancerous lesion.

Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia, Usual Type

Epidemiology

The vast majority of in situ squamous lesions of the vulva, comprising 82.3–98 % of reported series, are uVIN [28, 51, 55, 56], and the increasing incidence of VIN since the 1970s [16, 57–63] as well as a decreasing age of diagnosis [29, 60, 64], has been largely attributed to the role of HPV in the pathogenesis of this disease. The factors known to increase the risk of developing uVIN are principally related to the risk of contracting HPV or to the presence of established infection in the lower anogenital tract. Thus, early age of first intercourse; a history of multiple sex partners, of genital warts, and of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; and immunosuppression are all associated with increased risk. The incidence has been shown to increase in women up to the fifth decade and then to decline gradually [16, 57].

The average age of patients with uVIN in recent studies ranges from 38 to 53 years [31, 32, 41, 47, 51, 58, 65–69]. Like those with cervical HPV-related disease, the majority of patients are smokers [70–72], and anywhere from 25 % to 75 % [20, 31, 32, 52, 58, 67, 71, 72] have been reported to have HPV-associated lesions elsewhere in the lower anogenital tract, depending on how many sites were examined and how disease was defined. Prior, synchronous or subsequent squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva is found in approximately one quarter of patients [41, 51, 73].

Morphology

Grossly, uVIN may appear as a white, erythematous, or pigmented plaque, papule, or polypoid area on the affected epithelium, dependent on the histomorphology of the particular lesion. Multiple synchronous lesions are reported to be present in 36–77.5 % [32, 67, 69, 74], a finding which is more common in younger women.

The precancerous nature of uVIN has never been doubted, largely because the morphology is so abnormal. Microscopically, two distinct and strikingly abnormal histologic patterns of uVIN have been described. They are not, however, mutually exclusive. Mixed forms are common and may be diagnosed as such, and, as there is no clinical difference between them, it is acceptable to abstain from designating either specific type as long as the distinction from dVIN is clear. It is also not uncommon for uVIN of either warty or basaloid type to be seen adjacent to or admixed with condyloma acuminatum, particularly in immunosuppressed patients [75]. As the clinical behavior will be dominated by the uVIN in these cases, it is imper ative that the uVIN be recognized and diagnosed correctly.

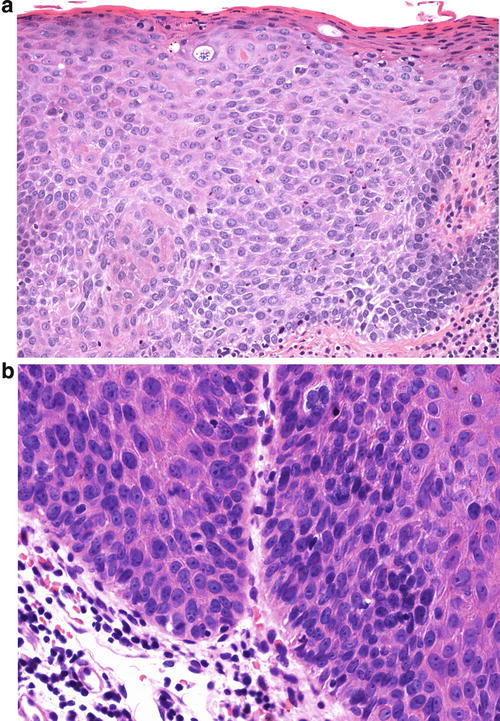

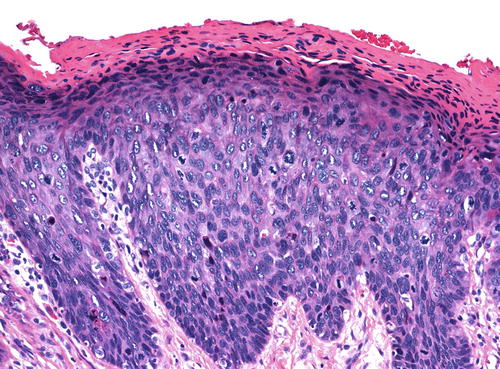

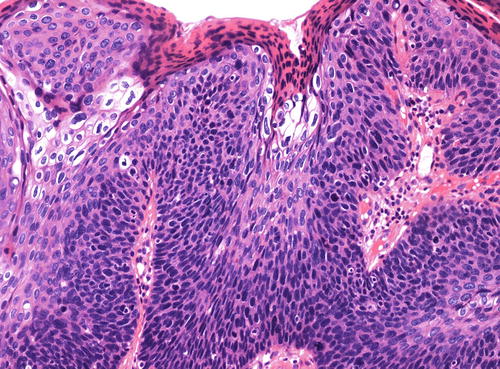

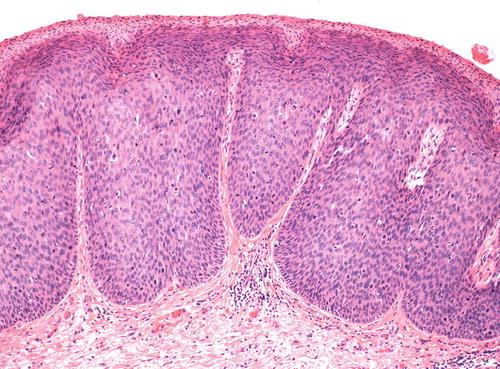

The warty type of uVIN is so named because of the spiky or undulating surface which lends them an exophytic gross appearance similar to condyloma. In this type of uVIN, there is usually striking acanthosis and hyperkeratosis, often accompanied by hypergranulosis and parakeratosis (Fig. 9.1). The thickened epithelium is disorganized and cellular maturation is markedly decreased, although the most superficial layers retain some degree of maturation and typically show at least focal koilocytic change (Fig. 9.2). Extreme cellular pleomorphism is characteristic, often with numerous multinucleated, apoptotic, and dyskeratotic forms (Fig. 9.3). There is usually moderate to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm in the more superficial layers, and intercellular bridges and cell borders are well defined (Fig. 9.4). Nuclear atypia is pronounced, with irregular nuclear membranes and coarsely granular, hyperchromatic chromatin (Fig. 9.5). Mitotic activity is readily apparent throughout all layers of the epithelium, including abnormal mitotic figures (Fig. 9.6).

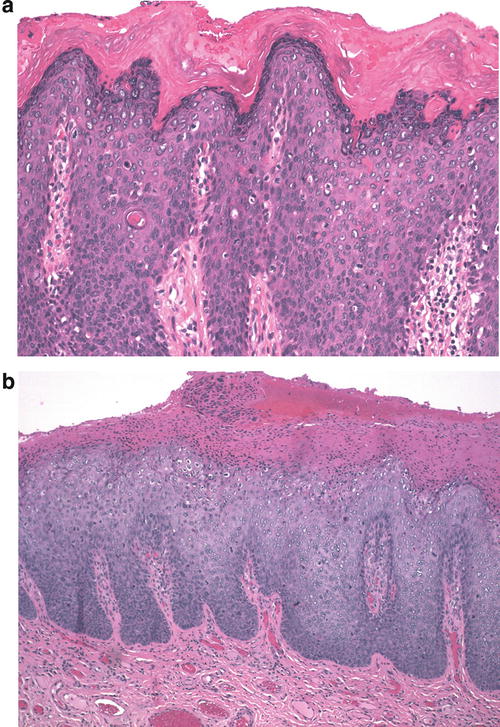

Fig. 9.1

(a) This case of uVIN, warty type, shows a thickened epithelium (acanthosis) with an undulating surface, hypergranulosis, and pronounced hyperkeratosis. (b) In this uVIN, the acanthotic epithelium is surfaced with a thick layer of parakeratosis

Fig. 9.2

Focal koilocytic change in the warty type of uVIN. Surface parakeratosis is also present

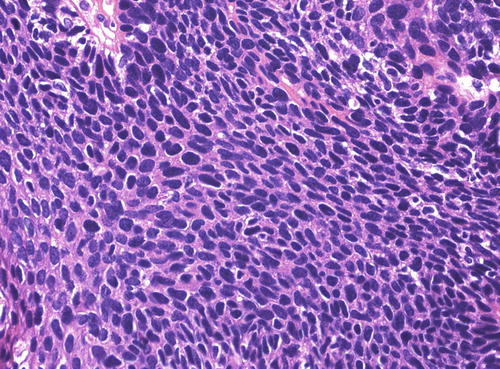

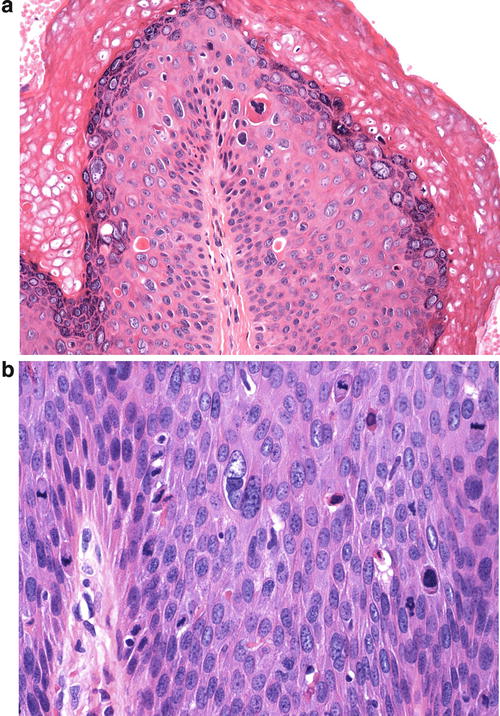

Fig. 9.3

(a) Extreme cellular pleomorphism , as seen here, is common in uVIN, warty type. Multinucleated cells, dyskeratotic cells, and apoptotic bodies are also present, along with surface hypergranulosis and hyperkeratosis. (b) Two large cells in the center of this field, one of which is multinucleated exemplify the cellular pleomorphism of uVIN, warty type. Again, small apoptotic bodies are also present. Several mitotic figures are also present in this field

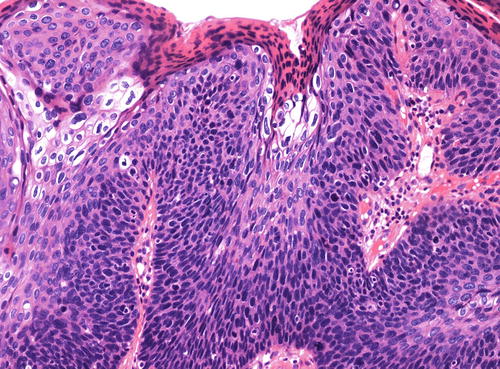

Fig. 9.4

(a) Prominent intercellular bridges account for the linear white spaces between many of the cells in this case of uVIN, emphasizing well-defined cell borders. The cells here show an appreciable amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. (b) Higher power shows the well-defined cell borders and hairlike extensions of intracellular bridges between the cells

Fig. 9.5

The nuclear features of uVIN, warty type, are evident here even at a relatively low power. In addition to the nuclear pleomorphism, there is coarsely granular, hyperchromatic chromatin with areas of nuclear clearing

Fig. 9.6

Numerous mitotic figures, including an abnormal, tripolar figure in the central part of the field

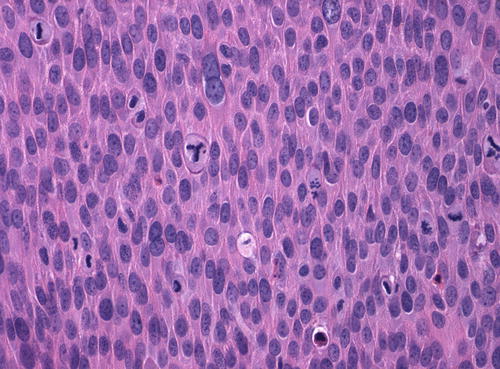

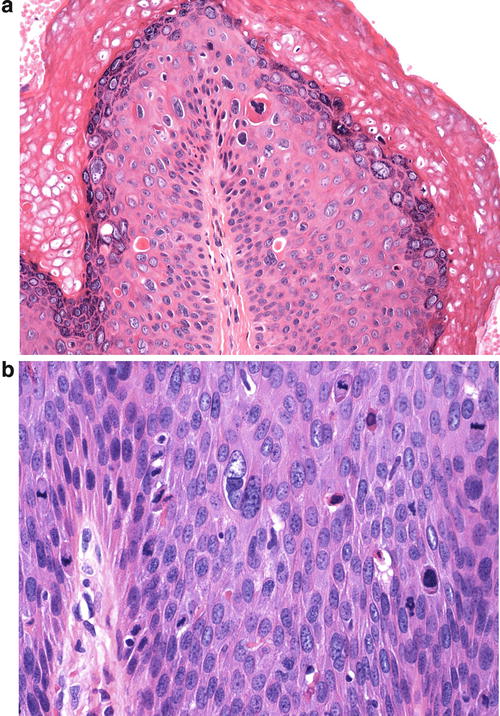

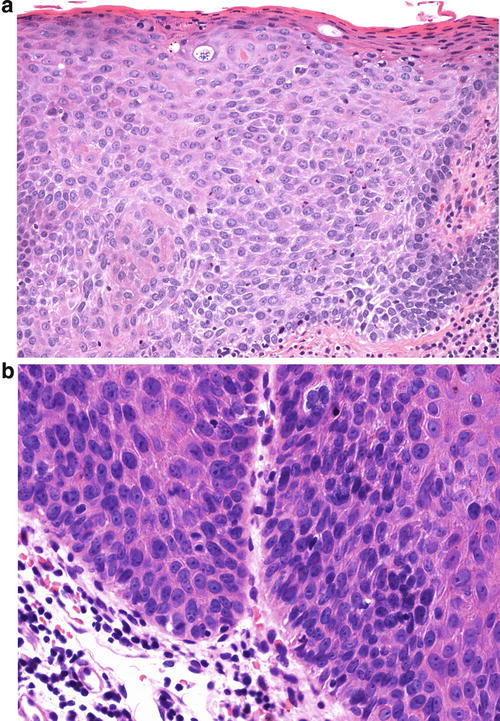

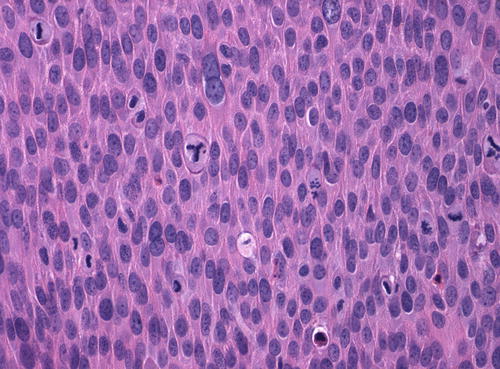

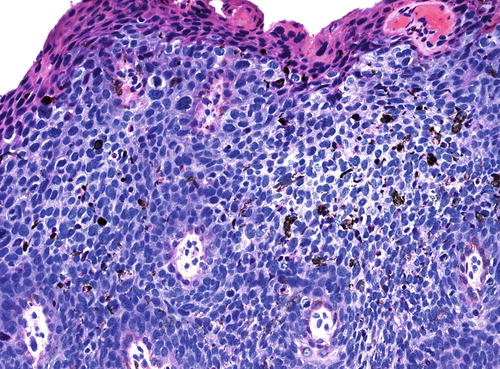

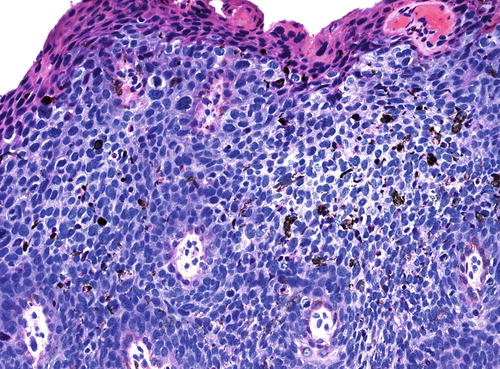

The basaloid type of uVIN has a relatively flat surface, and these lesions present grossly not as exophytic lesions but as macules or plaques. Like warty uVIN, the epithelium is thickened, and hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and koilocytosis may be present, but all of these features are seen to a lesser degree than in uVIN (Fig. 9.7). The lack of maturation in basaloid uVIN, however, is much more striking, and there is very little, if any, maturation even at the surface. Rather than the extreme pleomorphism seen in warty UVIN, in basaloid uVIN the cell population is quite uniform, comprised of small, immature cells with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm, with poorly defined cellular borders (Fig. 9.8). Mitotic activity is not significantly different from that seen in the warty type.

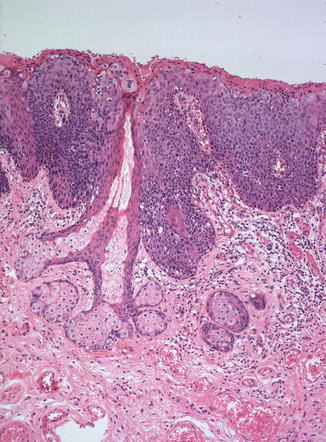

Fig. 9.7

Basaloid uVIN . The epithelium is acanthotic with a thin layer of surface parakeratosis, but the nuclei are more uniform and there is less cytoplasm than is typical of warty uVIN

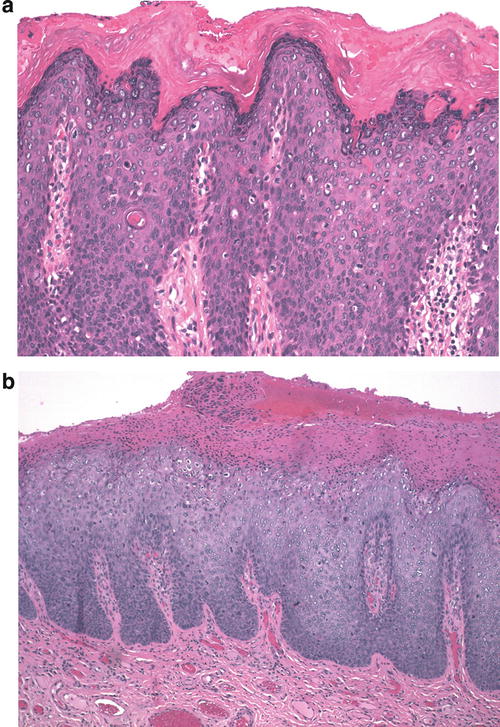

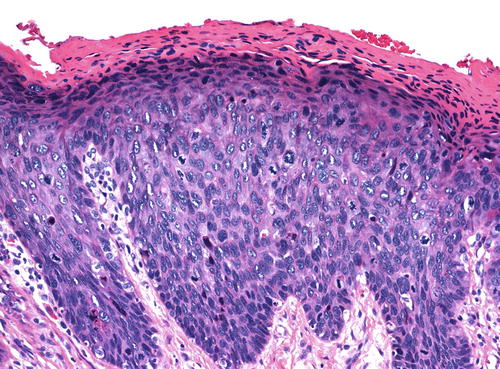

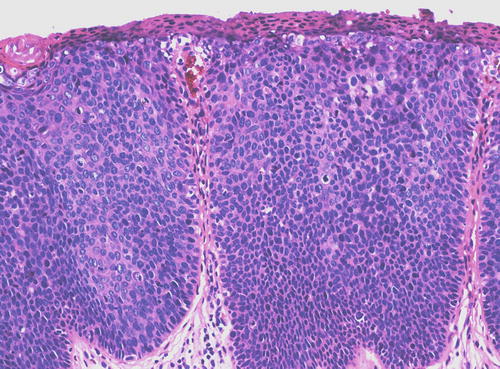

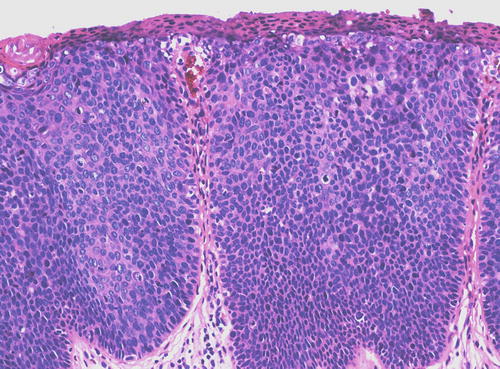

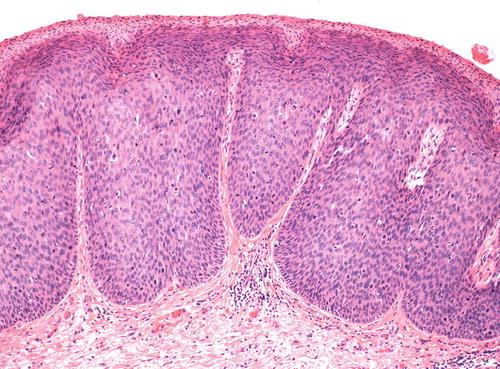

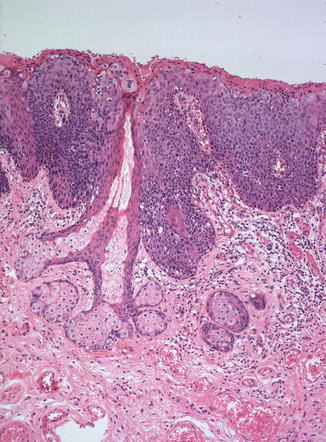

In both types of uVIN, the rete pegs are often widened and deepened while the dermal papillae are narrowed and extend more superficially than normal (Fig. 9.9). Both types of uVIN may contain intracellular and extracellular pigment, sometimes quite prominent (Fig. 9.10), which should not be taken as evidence of melanocytic differentiation. Both also commonly involve skin appendages (Fig. 9.11), which may be misconstrued as invasion, particularly in a superficial biopsy. At the same time that it is important to avoid making this mistake, it should be kept in mind that it is not uncommon for a lesion considered to be uVIN to be discovered to have focal invasion upon pathologic evaluation of the excised specimen. Such occult cancers, usually with only minimal invasion, have been reported in up to 22 % of cases [32, 67, 72, 74, 76–78], a finding which not only bolsters the concept of uVIN as a precancerous lesion but also demands careful evaluation of all excisions.

Fig. 9.9

Wide, deep rete pegs with narrow dermal papillae extending far superficially, a characteristic architecture seen in both types of uVIN

Fig. 9.10

Clusters of coarse pigment granules are scattered throughout the epithelium in this case of warty uVIN, which would have given the lesion a brown appearance grossly

Fig. 9.11

VIN extending down a sebaceous gland . Note how much deeper the lesion penetrates along this gland than does the adjacent lesion

Rare variants of VIN have been described with pagetoid or mucinous morphology. These are usually seen in association with concurrent invasive carcinoma and with associated intraepithelial squamous cell abnormalities with the more typical appearance of uVIN. Lesions with a pagetoid morphology , in which clusters and nests of atypical squamous cells are found scattered within an otherwise normal epithelium rather than replacing the full thickness, have been confirmed to express p16 and half have been found to have integrated HPV, consistent with the observed relationship to uVIN [79, 80]. Immunohistochemistry has provided further evidence that these cells represent an aberrant morphology of uVIN rather than Paget disease as they do not stain with mucin or CEA, a finding which may be useful in difficult cases [79, 80]. Another VIN variant in which cells with mucinous cytoplasm are admixed throughout the epithelium of an otherwise typical uVIN has been termed “VIN with mucinous differentiation” [81]. This variant has also been shown to be positive for p16 and to contain HPV 16, in keeping with the observed association with uVIN.

Immunophenotype

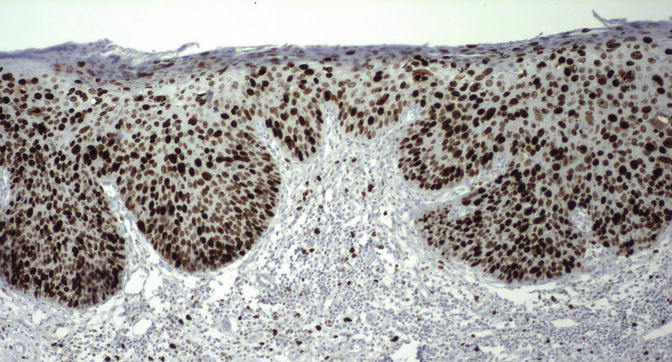

As p16 is overexpressed as a result of aberrant cell cycle activation by viral oncoproteins, its expression is extremely sensitive and specific for the presence of virus (124). Consequently, uVIN stains strongly for p16 in 95–100 % of cases [50, 65, 82–84], as do their associated carcinomas [85]. Even HPV-negative lesions with the histologic appearance of uVIN have been found to express p16 in the majority of cases [85], suggesting these cases represent failure of detection rather than true absence of the virus. The pattern of staining is either nuclear or nuclear and cytoplasmic, involving a continuous area or “block” of epithelium from the basal layer through at least the bottom third of the epithelial thickness (Fig. 9.12). A similar pattern may be seen with proExC, another marker of active HPV infection [86]. Ki-67/MIB1, also a marker of cell cycle activation, is likewise strongly expressed in uVIN, showing nuclear positivity in the majority, if not all, cells throughout the full thickness of the epithelium (Fig. 9.13). Studies of p53 expression in uVIN have been somewhat contradictory, with some studies reporting varying levels of overexpression [50, 87, 88] and some reporting no expres sion at all [65], but p53 does not appear to play a significant role in HPV-associated tumors, which show very low p53 expression [50, 87], and it does not appear to be useful marker in uVIN.

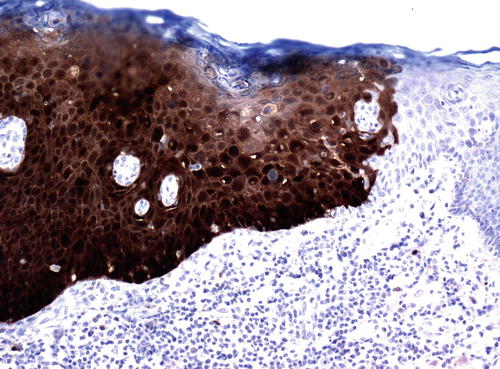

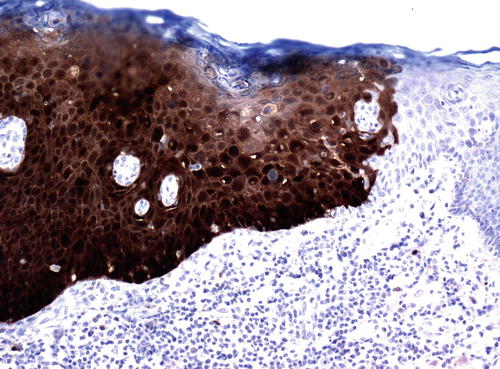

Fig. 9.12

The pattern of p16 staining in uVIN. There is intense nuclear and cytoplasmic staining through the entire epithelial thickness in this lesion. Note the clear distinction for the adjacent normal epithelium, which is p16 negative

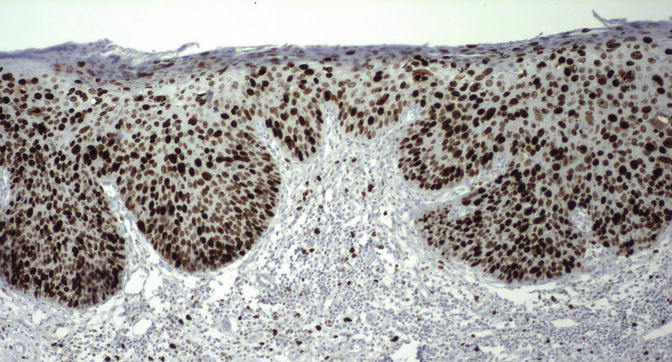

Fig. 9.13

The majority of the cells in uVIN show strong nuclear positivity for Ki/67/MIB- 1 through all layers of the epithelium

Molecular Findings

That tumors of basaloid and warty morphology have been show n to have adjacent uVIN in 53.8–100 % of cases [23, 29, 50, 56, 89, 90] has been taken as strong evidence that uVIN gives rise to these tumors. More significantly, over the past two decades or so there has been an increasing understanding of the molecular alterations underlying the profoundly altered epithelial morphology of uVIN, which has further clarified its relationship to invasive disease. The relationship of uVIN and vulvar cancer to HPV infection, with high-risk viral types identified in 57–97.1 % of uVIN [47, 56, 65, 68, 70, 71, 91–97] and from 69.4 % to 90 % [50, 52, 84, 89, 93] of basaloid/warty carcinoma, has provided some of the strongest evidence that uVIN is truly a precancerous entity. Over the last three decades, it has become firmly established that HPV is a causative agent of a variety of cancers, ultimately leading to official classification as a carcinogen by the WHO in 2005 [98]. The mechanisms by which the virus acts to induce neoplasia through the actions of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7, which have been shown to interfere with the normal cell cycle in such a way as to promote genetic instability and the continued proliferation of genetically altered cells [83, 98, 99], have become quite well understood, primarily through work done on cervical cancer and its precursors.

The natural history of HPV infection of the vulva remains less well understood than in the cervix. This is in part due to the fact that cervical disease is more common and that the asymptomatic cervix is routinely screened for the presence of HPV, while the vulva is not. This has provided an abundance of cervical material for study, allowing investigators to elucidate the course of HPV-induced disease in this site in great detail, while data involving vulvar lesions is relatively scant. The few studies that have looked for HPV on the vulva of asymptomatic patients have shown that nearly three quarters of women with HPV detected in the cervix will also have the virus detected on the vulva [70, 100]. In one prospective study of HPV-naïve women, of 1196 incident high-risk HPV infections of the vulva, only 11 uVIN developed [91] demonstrating that the vast majority of patients will clear the infection without ever developing VIN. For those few patients who do, the mean time from incident HPV infection to VIN was found to be 18.5 months [91]. The highest rates of detection of high-risk virus, not surprisingly, are seen in patients with current uVIN lesions, and in most cases, the detection is in multiple sites (27). The rate of virus detection drops by about half in patients with a history of treated VIN [70] consistent with the finding that half of vulvar infections have been found to persist after treatment [91].

The distribution of HPV subtypes is different in uVIN than in high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix. In both sites, HPV 16 is the most common subtype, but in the cervix, the second most common subtype is HPV 18, while in the vulva HPV 18 is only rarely detected and the second most common subtype is HPV 33 [20, 52, 56, 89, 91, 94, 96, 101–105]. Because many studies, following the lead established in cervical research, have limited their analysis to HPV types 16 band 18, this may account for some of the discrepancies between the rates of HPV positivity in the cervix compared to the vulva. Interestingly, there is evidence that it is a single infection that is responsible for the multiple lesions seen in patients with multifocal and multicentric disease. In the majority of cases analyzed, the same viral subtype was identified in both the vulvar and cervical lesions [52], or in multiple vulvar lesions of the same patient [106].

This integration of the viral genome is considered a critical step in viral carcinogenesis. Although it is not required for progression of disease, viral integration results in increased expression of viral oncogenes E6 and E7, and it makes sense that it would increase the likelihood of progression. Studies in vulvar disease support the significance of viral integration in the pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma and also support the idea that the disease evolves through a precursor VIN lesion. In one case of HPV 16-related carcinoma with adjacent uVIN, the virus was detected in both integrated and episomal form in both the uVIN and the tumor, but the integrated form was predominant in the tumor [97]. A later study on a single patient with multifocal uVIN and an associated carcinoma was shown to have only episomal HPV 16 in two loci of uVIN, but had integrated virus in two other uVIN sites and in the tumor [107]. In a large r study, integrated HPV was found in 24 of 25 uVIN adjacent to squamous cell carcinoma [104]. In another, viral integration was found in 38 % of HPV 16- or HPV 18-positive cases of uVIN, all of which were multifocal and multicentric and one of which progressed to invasive carcinoma [106]. In addition, this study found the same viral-type transcript pattern in all specimens from the same patient with multiple foci of disease in 83.3 % of cases, suggesting the multiple lesions are monoclonal. One study detected the same viral integration site in vulvar lesions as in previously diagnosed cervical lesions of the same patient, raising the possibility that a single clone might be responsible for disease in multiple sites [108].

Other genetic similarities have been found between uVIN and vulvar squamous cell carcinoma to support the evolution of the former to the latter. Clonal evolution of VIN lesions was first hypothesized in 1981, when studies by Fu and Wilkinson showed all of the cases of VIN they analyzed were aneuploid [109, 110]. Further studies confirmed a monoclonal origin in the majority of cases [97, 111, 112], and comparison of in situ lesions and the associated invasive tumors has shown the same clone in both lesions [112]. Allelic imbalance has been demonstrated in the majority of uVIN [113] and to be higher in VIN associated with cancer than in VIN alone, suggesting that increasing genetic instability drives the progression to invasive disease [114]. Further analysis has shown that the tumors associated with uVIN, as well as the uVIN in different sites, when multifocal lesions are present, may not be completely identical [112, 114], suggesting continued clonal evolution within the invasive tumor. Some specific genetic alterations have been described in uVIN, including loss on chromosome 17 and gains in the long arm of chromosome 3 [63, 65, 115]. The latter alteration, reported in up to 50 % of uVIN, is of particular interest as the same alteration is also commonly seen in squamous cell carcinomas of both vulva and cervix [65, 115, 116].

Patient Outcome

Recurrence of uVIN is common and has been reported in 28.7–72.5 % of cases [20, 31, 32, 66, 71, 72, 117–119]. Most recurrences have been reported within 4 years [117, 118], but patients remain at risk for life and close life-long follow-up is imperative. Multifocal infection sites are likely responsible for at least part o f the recurrence risk [70]. Recurrences consist of both treatment failures, where the lesion recurs in the same location treated previously and of new “field effect” lesions related to the progression of HPV infection at another site. Only one study has considered the two separately, finding an equal number of both, but that recurrence at the site of previous treatment appeared in a median time of 2.4 years as opposed to a median time of 13.5 years in the “field effect” lesions [64]. Most studies have found recurrence to be more likely if lesions are multifocal [31, 32, 69, 71, 77, 117, 119], but some have failed to find a correlation between recurrence and multifocality [67, 120]. Similarly, most studies have found recurrence to be more common if the initial excision margins are positive [31, 64, 66, 67, 77] and if the patient continues to smoke [19, 66, 72, 117], although one study has challenged both of these findings [120]. Immunosuppression [117], cryosurgical treatment [67], and larger lesion size [66] have all been associated with increased risk of recurrence. Whether surgical excision or laser treatment has a higher risk of recurrent disease remains controversial, with studies showing conflicting results [117, 118]. Not surprisingly, given its viral etiology, the immune microenvironment in uVIN has recently been shown to differ from normal controls [121] and the specific alteration of increased CD14-positive macrophages to correlate with recurrence and progression of disease [122].

Subsequent invasive squamous carcinoma of the vulva is reported in treated patients in 2.3–16 % of reported cases, with most studies finding progression to occur in less than 7 % of patients and in less than 8 years [20, 31, 32, 58, 64–67, 69, 71, 117, 118, 123]. Progression has been reported to occur more frequently and rapidly in patients who are immunosuppressed [71, 117], in multifocal disease [117], in women who continue to smoke [117], and in patients of advanced age [58] although not all studies have confirmed these findings [66]. The median time to progression of a uVIN lesion to invasive squamous cell carcinoma has been reported from 41.4 to 109 months [58, 66, 67, 117], and cases have been reported up to 18 years following initial treatment [123]. One study reported two peaks in progression, the first at 2–3 years and the second at 7–8 years post treatment [117]. For obvious reasons, fewer studies have been able to report on the progression rate in untreated disease, but a small number of patients who have refused initial treatments have been followed and most have been found, ultimately to progress to invasive disease within 1–8 years [64, 67, 123].

A small subset of patients with the histologic findings of uVIN will regress with no further treatment. This phenomenon was first reported as “reversible vulvar atypia” by Friedrich in 1972 [124]. The term “Bowenoid papulosis” was coined to describe the condition in 1979, a term that describes a subset of disease which is distinct clinically but not morphologically, and therefore no longer accepted as a pathologic diagnosis but remains in clinical use. The patients in this fortunate group are usually young and often pregnant, with multiple pigmented papular lesions [64, 67, 125]. In recent case series, they have comprised 1.2 % [67] and 12 % [64] of patients with VIN, and the median time to regression was reported as 9.5 months [64].

Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia, Differentiated Type

Epidemiology

Although the increasing incidence in VIN seen since the 1970s is predominantly due to uVIN in young women, as discussed above, the diagnosis of dVIN has also been seen with increasing frequency in recent years [58]. Nonetheless, it remains a minority of VIN, comprising only 2–18 % of cases [28, 41, 51, 55]. Unlike uVIN, however, the increasing frequency of diagnosis of dVIN is most likely due to increased recognition of the disease, rather than any true increase in its incidence. The reasons for the relative rarity of the diagnosis of dVIN as compared to uVIN are as yet incompletely understood. It may truly be an uncommon occurrence, although it seems likely that both misdiagnosis as benign reactive disease and its rapid progression to invasive disease contribute to its underrecognition an underreporting. Over the last decade and a half, as it has become clear that there are two different pathways to squamous carcinoma of the vulva, the awareness and acceptance of the diagnosis of dVIN appear to have increased, and it is likely to be diagnosed with greater frequency in the future.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree