JOHN W. MORONEY  CHARLES KUNOS

CHARLES KUNOS  EDWARD J. WILKINSON

EDWARD J. WILKINSON  CHARLES F. LEVENBACK

CHARLES F. LEVENBACK

INTRODUCTION

Malignant tumors of the vulva are rare and account for less than 5% of all cancers of the female genital tract. In 2012, there will be an estimated 4,490 new cases of, and 950 deaths from, invasive vulvar carcinoma in the United States (1). Because of its low incidence, most primary care providers will never encounter a patient with vulvar cancer. Although a rare patient with vulvar cancer will present without symptoms, the vast majority of women with vulvar cancer initially present with complaints such as vulvar irritation, pruritis, pain, or a mass that does not resolve. The interval between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of cancer can be protracted when a woman who is embarrassed by new vulvar symptoms delays seeking care, or a physician prescribes empiric topical therapies without a proper physical examination or tissue biopsy confirmation. Jones and Joura evaluated the clinical events preceding the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and found that 88% of patients had experienced symptoms for more than 6 months, 31% of women had 3 or more medical consultations prior to the diagnosis of vulvar carcinoma, and 27% had applied topical estrogen or corticosteroids to the vulva (2).

The vulva is covered by keratinized squamous epithelium; accordingly, the majority of malignant vulvar tumors are squamous cell carcinomas. Consequently, our current understanding of the epidemiology, spread patterns, prognostic factors, and survival data for vulvar cancer is largely derived from experience with squamous cell carcinomas. Malignant melanoma is the second most common cancer of the vulva. Although there is some consensus regarding the behavior and treatment of vulvar melanoma, its rarity has thus far precluded the conduct of robust, prospective clinical trials. A number of other malignant tumors, both epithelial and stromal in origin, arise from normal vulvar tissue and are discussed in detail later in this chapter. Finally, the vulva may be secondarily involved with malignant disease originating in the cervix, bladder, anorectum, colon, breast, or other organs.

The traditional therapeutic approach to vulvar cancer has been radical surgical excision of the primary tumor and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. Experience has shown that survival is improved with the administration of postoperative radiation therapy to selected patients deemed to be at high risk for locoregional failure. More recently, the use of neo-adjuvant radiotherapy with concomitant radio-sensitizing chemotherapy has proven to be effective in treating vulvar cancer patients for whom radical surgery would be either too morbid or technically not feasible. New surgical techniques, including sentinel lymph node biopsy, hold the promise of better outcomes for patients with early disease. An individualized approach to vulvar cancer management, often employing multiple modalities in an effort to achieve disease control with better cosmetic results and sexual function, is now the norm. These and other topics pertinent to the principles of management of women with vulvar cancer are the subjects of this chapter.

ANATOMY

The vulva consists of the external genital organs—including the mons pubis, labia minora and majora, clitoris, vaginal vestibule, and perineal body—and their supporting subcutaneous tissues. The vulva is bordered superiorly by the anterior abdominal wall, laterally by the labiocrural fold at the medial thigh, and inferiorly by the anus. The vagina and urethra open onto the vulva. The mons pubis is a prominent mound of hair-bearing skin and subcutaneous adipose and connective tissue that is located anterior to the pubic symphysis. The labia majora are two elongated skin folds that course posterior from the mons pubis and blend into the perineal body. The labia minora are a smaller pair of skin folds medial and parallel to the labia majora that extend inferiorly to form the margin of the vaginal vestibule. Superiorly, the labia minora separate into 2 components that course above and below the clitoris, fusing with those of the opposite side to form the prepuce and frenulum, respectively. The skin of the labia minora contains sebaceous glands near its junction with the labia majora, but it is not hair-bearing and it has little or no underlying adipose tissue. The clitoris is supported externally by the fusion of the labia minora (prepuce and frenulum) and is approximately 2 to 3 cm anterior to the urethral meatus. It is composed of erectile tissue organized into the glans, body, and two crura. Two loosely fused corpora cavernosa form the body of the clitoris and extend superiorly from the glans, ultimately dividing into the two crura. The crura course laterally beneath the ischiocavernosus muscles and attach to the ischial rami.

The vaginal vestibule is situated in the center of the vulva and is homologous to the male distal urethra. It has squamous mucosal epithelium that is demarcated bilaterally and posteriorly by the junction with the keratinized epithelium at Hart’s line, located on the medial labia minora and inferiorly on the perineal body. The vagina, urethra, periurethral glands, minor vestibular glands, and the Bartholin’s glands open onto the vestibule. Anteriorly, the minor small vestibular glands are located beneath the vestibular mucosa and open onto its surface predominantly on the more anterior vestibule. The vestibular bulbs, a loose collection of bilateral erectile tissue covered superficially by the bulbocavernosus muscle, are located laterally. The Bartholin’s glands, two small, mucus-secreting glands situated within the subcutaneous tissue of the posterior labia majora, have ducts opening onto the posterolateral portion of the vestibule. The perineal body is a 3 to 4 cm band of skin and subcutaneous tissue located between the posterior extensions of the labia majora. It separates the vaginal vestibule from the anus and forms the posterior margin of the vulva.

Vascular Anatomy and Neurologic Innervation

The vulva has a rich blood supply derived primarily from the internal pudendal artery, which arises from the anterior division of the internal iliac (hypogastric) artery, and the superficial and deep external pudendal arteries, which arise from the femoral artery. The internal pudendal artery exits the pelvis and passes behind the ischial spine to reach the posterolateral vulva, where it divides into several small branches to the ischiocavernosus and bulbocavernosus muscles, the perineal artery, artery of the bulb, urethral artery, and dorsal and deep arteries of the clitoris. Both external pudendal arteries travel medially to supply the labia majora and their deep structures. These vessels anastomose freely with branches from the internal pudendal artery. Innervation of the vulva is derived from multiple sources and spinal cord levels. The mons pubis and upper labia majora are innervated by the ilioinguinal nerve (L1) and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (L1–2). Either of these nerves may be easily injured during pelvic lymph node dissection, with resulting paresthesias. The pudendal nerve (S2–4) enters the vulva in parallel with the internal pudendal artery and gives rise to several branches that innervate the lower vagina, labia, clitoris, perineal body, and their supporting structures.

Groin Anatomy and Lymphatic Drainage

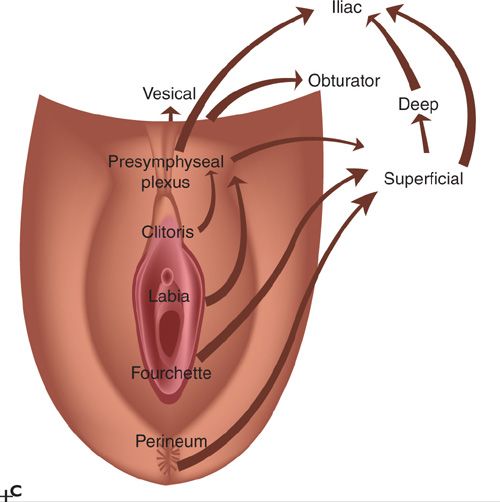

Vulvar lymphatics run anteriorly through the labia majora, turn laterally at the mons pubis, and drain primarily into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Dye studies by Parry-Jones demonstrated that vulvar lymphatic channels do not extend laterally to the labiocrural folds and do not cross the midline, unless the site of dye injection is at the clitoris or perineal body (3).

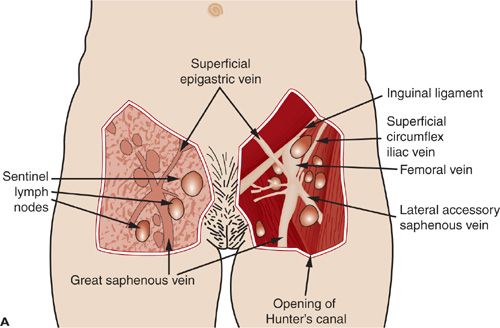

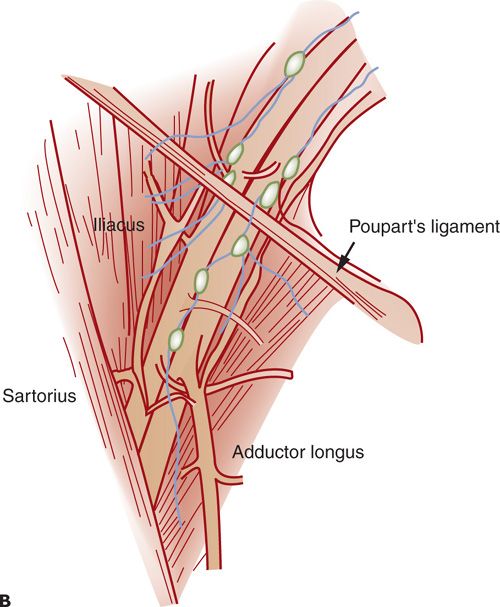

The vulvar lymphatics drain to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes located within the femoral triangle formed by the inguinal ligament superiorly, the border of the sartorius muscle laterally, and the border of the adductor longus muscle medially. There are 8 to 10 inguinal lymph nodes lying along the saphenous vein and its branches between Camper’s fascia and fascia overlying the femoral vessels (Fig. 19.1 A–C) (4). The first draining lymph node is termed the sentinel lymph node (SLN) and can be identified only by the use of various lymphatic mapping techniques. The SLN is frequently found medial to the femoral vein just above the adductor muscle. Second echelon lymph nodes may be in the groin or pelvis. Cloquet’s node, or the most superior inguinal lymph node, is located under the inguinal ligament. Lymphatic drainage from the SLN is sequentially to the external iliac, common iliac, and aortic lymph nodes (Fig. 19.1 A–C).

The fossa ovalis is a crescent-shaped terminus of the fascia lata and the site where vascular and lymphatic structures meet with the femoral vessels. The cribriform fascia is a term widely used in the literature describing the anatomy of the groin and is said to cover the fossa ovalis. The cribriform fascia is hard to identify and is more of a “lamina” than an actual fascia. SLN biopsy with lymphatic mapping deemphasizes the need to identify the cribriform structure and focuses the surgeon’s attention on functional in vivo surgical anatomy rather than textbook descriptions of lymph node locations.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

An estimated 4,490 women were diagnosed with vulvar cancer in the United States in 2012, and approximately 950 will die of the disease (1). Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 3% to 5% of all gynecologic malignancies and 1% of all carcinomas in women, with an incidence rate of 1 to 2 per 100,000 women (1). Most vulvar cancers occur in postmenopausal women in the seventh decade, although more recent reports have identified a trend toward younger age at diagnosis (5, 6). Earlier observational studies suggested associations between hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity and vulvar carcinoma; however, subsequent analyses have not confirmed the prognostic significance of these diagnoses (7).

Several infectious agents have been proposed as possible etiologic agents in vulvar carcinoma, including granulomatous infections, herpes simplex virus, and, most notably, human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV infection is present in virtually 100% of women with cervical cancer. The relationship between HPV infection and vulvar cancer is much less straightforward. This is likely due to the different etiologic pathways that are believed to be responsible for vulvar cancer. These different etiologic pathways are discussed in detail in the chapter on preinvasive disease; however, because of subject matter overlap, some of the data related to HPV and invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva are discussed here.

Vulvar condylomas have a well-described relationship to HPV, and strong associations between vulvar condylomas and the later development of vulvar cancer have been identified (8). The role of HPV in the development of premalignant and malignant lesions of the vulva has become clearer as molecular techniques for HPV detection and mutational analyses have improved (9). Earlier studies identified HPV DNA in both invasive and carcinoma in situ lesions via immunohistochemistry. More recent studies have used DNA detection methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and in situ hybridization to detect high-risk serotypes (9). Among HPV serotypes, 16 is the most common; however, many other serotypes, including 18, 31, 33, and others, have been implicated (9). HPV DNA can be identified in approximately 85% of intraepithelial lesions (range, 42% to 100%), but is seen in only 10% to 50% of invasive lesions (9). The reason such a wide range of associated HPV is seen associated with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) and vulvar cancer has to do with differences between studies regarding which VIN subtypes (usual or differentiated) are being studied, different DNA detection methods with different sensitivity, and differences between studies regarding which HPV serotypes are being assayed.

Although HPV DNA is associated with the vast majority of intraepithelial lesions (~85%), it is much less commonly seen in association with invasive lesions (~40%) (9). Marked differences between HPV positivity in VIN and vulvar cancers are also seen with respect to age. Basta et al. conducted a retrospective case control study examining the coexistence of HPV and the incidence of both VIN and stage I vulvar cancer. HPV infection was present in 61.5% of cases of VIN and vulvar cancer in women aged less than or equal to 45 years, and in 17.5% or women older than 45 years (10).

FIGURE 19.1. These historic figures illustrate some of the problems depicting the lymphatic anatomy of the groin. A and B illustrate vessels, muscles, and nerves accurately. A refers to sentinel nodes; however, this is based on location rather than a mapping procedure, which is misleading. B shows nodes between the femoral artery and vein. Lymph nodes between the vessels are common in the pelvis but not in the groin. C: shows direct drainage from the clitoral area of the vulva to pelvic lymph nodes. This drainage pattern is not observed with preoperative or intraoperative lymphatic mapping studies.

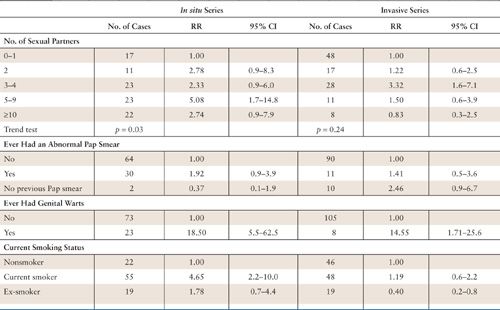

Chronic immunosuppression and tobacco smoking have also been linked as cofactors for the development of invasive vulvar cancer (11,12). Vulvar cancer incidence is increased in female renal transplant patients as well as women with HIV and AIDS (11,13). Smoking is an independent risk factor for the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, although the reason for this is unclear. One hypothesis is that genetic variations in T-cell-mediated IL-2 responses among smokers may explain differential susceptibility to the development of squamous vulvar carcinomas (12). Significant correlations between smoking status, historical number of sexual partners, history of genital warts, and a history of an abnormal Pap smear have been detailed by Brinton et al. (Table 19.1) (7).

Chronic vulvar inflammatory lesions, such as vulvar dystrophies, including lichen sclerosus (LS), lichen planus, lichen simplex chronicus, squamous cell hyperplasia, and vulvar intra-epithelial neoplasia II/III (usual as well as differentiated types), particularly differentiated VIN (dVIN), have been suggested as precursors of invasive squamous cancers (14, 15). Carli et al. suggested a possible role of LS as a precursor to vulvar cancer based on their observation that 32% of vulvar cancer cases not related to HPV were associated with LS (16). More recently, in a pathologic reevaluation of patients with a diagnosis of LS who were followed clinically for a minimum of 10 years, van de Nieuwenhof and colleagues identified concordant diagnoses of LS in 58/61 patients who did not progress to cancer, and concordant diagnoses of LS in only 29/60 patients who were identified with a subsequent diagnosis of vulvar cancer. The majority of patients reclassified as having something other than LS were considered to have dVIN (25/31 patients). This study highlights dVIN as a uniquely at-risk histology that deserves prompt treatment and close follow-up. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia is often found in lesions, previously diagnosed as LS, that have progressed to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (15).

Relative Risks of In Situ and Invasive Vulvar Cancers by Selected Risk Factors |

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Brinton LA, Nasca PC, Mallin K, et al. Case-control study of cancer of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:864.

In an observational study of women with carcinoma in situ, 7 of 8 untreated cases progressed to invasive carcinoma within 8 years, and 4 of 105 treated women presented with invasive tumors from 7 to 18 years later (17). In a subsequent study of 405 cases of VIN 2 to 3, Jones et al. found that 3.8% of patients had developed invasive cancer despite therapy, and 10 untreated patients had developed invasive cancer in 1.1 to 7.3 years (mean, 3.9 years) (18). Although some intraepithelial lesions regress spontaneously, it appears that a significant number persist or progress to invasive cancer.

Trimble et al. postulated that squamous carcinoma of the vulva may represent a final common endpoint of heterogeneous etiologic pathways (19). According to their studies, two histologic subtypes, those with basaloid or warty features, are associated with HPV, whereas keratinizing squamous carcinomas are not. Furthermore, basaloid or warty carcinomas are associated with classic risk factors for cervical carcinoma, including age at first intercourse, lifetime number of sexual partners, prior abnormal Pap smears, smoking, and lower socioeconomic status. Keratinizing squamous carcinomas are weakly linked to these factors, and in some cases not at all.

Mitchell et al. evaluated 169 women with invasive vulvar cancers and noted that second genital squamous neoplasms occurred in 13% of cases (20). The risk of a second primary tumor was significantly increased in cancer cases with HPV DNA, intraepithelioid growth pattern, or adjacent dysplasia. These observations support the concept that some squamous lesions may be initiated by sexually transmitted viruses capable of producing neoplastic change within the entire field of the lower genital tract. The obvious clinical implication of this observation is that a patient with an established squamous lesion of the vulva, vagina, or cervix needs to be evaluated and monitored for new or coexistent lesions at other sites.

NATURAL HISTORY (PATTERNS OF SPREAD)

Vulvar cancers metastasize in 3 ways: (a) local growth and extension into adjacent organs, (b) lymphatic embolization to regional lymph nodes in the groin, and (c) hematogenous dissemination to distant sites.

Inguinal node metastasis can be predicted by the presence of multiple risk factors, including tumor diameter, higher histologic grade (degree of differentiation), depth of stromal invasion, and lymphovascular space invasion (21, 22). Clinically important observations regarding nodal metastases include the following: (a) inguinal nodes are the most frequent site of lymphatic metastasis; (b) in-transit metastases within vulvar epithelium and deep tissues are exceedingly rare, suggesting that most initial lymphatic metastases represent embolic phenomena; (c) Metastasis to the contralateral groin or deep pelvic nodes are unusual in the absence of ipsilateral groin metastases; and (d) nodal involvement generally proceeds in a stepwise fashion from the superficial inguinal to the deep inguinal and then to the pelvic nodes (21, 22).

Spread beyond the inguinal lymph nodes is considered distant metastasis (stage IVB). Such metastases occur either due to sequential lymphatic spread to secondary and tertiary nodal groups or as a result of hematogenous dissemination to more distant sites, such as bone, lung, or liver. Distant metastases are uncommon at initial presentation and are usually seen in the setting of recurrent disease.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Most women with vulvar cancer present with pruritus and a recognizable lesion. Selecting the most appropriate site for biopsy in women with condyloma, chronic vulvar LS, multifocal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (VIN 3), or Paget’s disease can be difficult, and multiple biopsies may be required. Optimal management for any patient presenting with a suspicious lesion is to proceed directly to biopsy under local analgesia. Tissue biopsies should include the cutaneous lesion in question and representative contiguous underlying stroma, so that the presence and depth of invasion (DOI) can be accurately assessed. Because DOI is a central issue in the management of vulvar cancer, punch biopsies are encouraged and shave biopsies are discouraged in the diagnosis of vulvar lesions. If invasion is suspected and a punch biopsy fails to confirm the clinical suspicion, then an incisional or excisional biopsy should be performed. Primary care physicians should be encouraged not to excise a lesion if avoidable, to facilitate the sentinel node procedure by a gynecologic oncologist. Figure 19.2 illustrates a relatively early-stage vulvar cancer.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The evaluation of a patient with vulvar cancer must take into consideration the clinical extent of disease and the presence of coexisting medical illnesses. Initial evaluation should include a detailed physical examination with measurements of the primary tumor, assessment for extension to adjacent mucosal or bony structures, and clinical evaluation of the inguinal lymph nodes. It is helpful to record the distance from vital structures such as the clitoris, urethral meatus, and anus, since these structures are a limiting factor for obtaining adequate surgical margins. Diagnostic imaging is not required in women with small primary lesions and normal body habitus. In obese women, the inguinal nodes are difficult to palpate and imaging may be helpful in identifying the presence of lymphadenopathy. Patients with large or fixed tumors, and those who are difficult to examine in the clinic, may benefit from an exam under anesthesia with cystourethroscopy and proctosigmoidoscopy. Figure 19.3 illustrates an advanced tumor, for which such an approach can help determine resectability.

FIGURE 19.2. Early-stage vulvar cancer.

Radiographic studies that have been described as beneficial are computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), ultrasound, and single photon emission CT (SPECT) (23–26). While newer imaging modalities can be of benefit in treatment planning, it is also important to note that published series are small, and no individual modality has been shown to be superior to others in terms of detecting metastatic or recurrent disease. The best modality might differ depending on the practice situation and skills of the diagnostic imaging consultants. Suspicious lymph nodes should be biopsied if the findings would alter the surgical plan. Because neoplasia of the female genital tract is often multifocal, evaluation of the vagina and cervix, including cervical cytologic screening, should always be performed in women with vulvar neoplasms (27). Lymphoscintigraphy will be discussed later in this chapter.

FIGURE 19.3. Advanced vulvar cancer.

STAGING

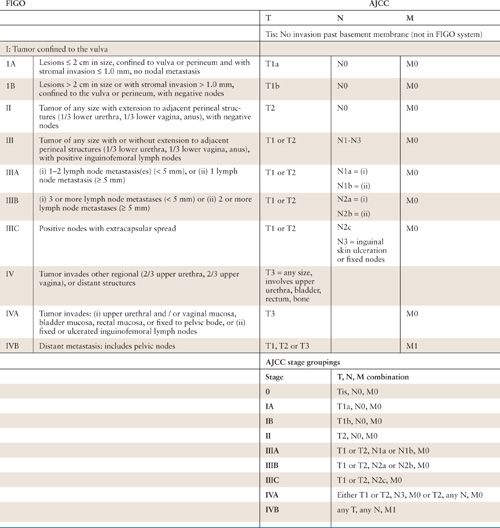

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) adopted a modified surgical staging system for vulvar cancer in 1989. This staging system was revised in 1995 and more recently in 2009 (Table 19.2) (28, 29). The 2009 revision was performed to address issues with the 1995 version, namely, the lack of a useful prognostic spread among stages, as well as significant prognostic heterogeneity among stage III patients. Since the 1995 revision, much has been learned about the significance of the number of involved nodes, the size of inguinal metastases, and nodal morphology.

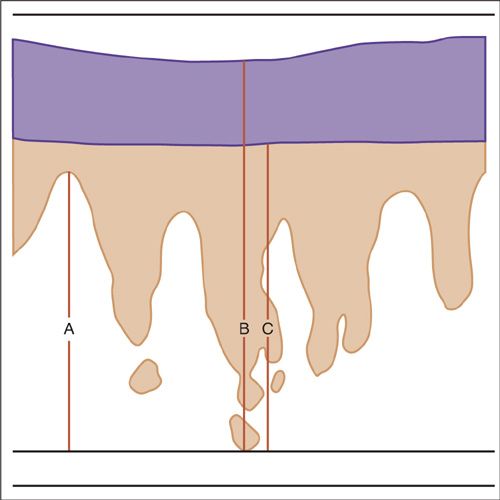

The technique recommended by the International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease, the International Society of Gynecologic Pathologists, the College of American Pathologists, and the World Health Organization to assess depth of stromal invasion is to measure from the base of the epithelium (epithelial–stromal junction) at the nearest superficial dermal papillae to the deepest point of tumor penetration (30). These definitions and methods of measurement are supported by the recent CAP-ASCCP LAST terminology project (Fig. 19.4) (31).

Integrated 2009 FIGO and AJCC Staging System for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva |

FIGURE 19.4. Methods for measurement for vulvar superficially invasive carcinomas. Depth of invasion (A) : the measurement from the epithelial stromal junction of the most superficial dermal papillae to the deepest point of invasion. This measurement is defined as the depth of invasion and is used to define stage IA vulvar carcinoma. The measurement (B) is the thickness of the tumor: from the surface of the lesion to the deepest point of invasion. Measurement (C) is from the bottom of the granular layer to the deepest point of invasion. This is also defined as thickness of the tumor in cases where there is a keratinized surface. The International Society of Gynecological Pathologists and the World Health Organization recommend that both the depth of invasion and the thickness of tumor, as well as the method of measurement, be defined in the pathology reports.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Wilkinson EJ. Superficial invasive carcinoma of the vulva. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1985;28:188–192.

Among squamous cell carcinomas limited to the vulva, those with a DOI less than or equal to 1 mm are associated with a <1% risk for lymph node metastasis. Tumors with a DOI of 1.1 to 3.0 mm are associated with lymph node metastases in 6% to 12% of patients, and approximately 15% to 20% of tumors with a DOI of 3.1 to 5.0 mm are associated with positive lymph nodes (32).

In the 2009 revision, all stage I and stage II patients have uninvolved lymph nodes. There is no clear definition of how many lymph nodes constitutes an adequate evaluation. SLN biopsy is not mentioned as a requirement; however, the emphasis on the size of micrometastases in stage III implies that an SLN biopsy is performed either alone or as part of a lymphadenectomy.

The new staging system adds 3 pathologic groupings within stage III (a, b, and c), each of which contains prognostic significance. These 3 groups are number of positive nodes, size of the largest inguinal node metastasis, and the presence or absence of extracapsular extension. These pathologic features have been shown in multiple studies to be the strongest predictors of mortality related to vulvar cancer (28).

The other notable difference in the new schema is the absence of stage difference based on unilaterality versus bilaterality of groin involvement; any groin metastasis is considered stage III disease. As in 1995, the 2009 FIGO staging guidelines for vulvar cancer were devised with correlation for the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification scheme (Table 19.2) (33). Tumor assessment is based on physical examination, with endoscopy in cases of bulky disease. Nodal status is determined by the surgical evaluation of the groins. The presence or absence of distant metastases should be based on an individualized diagnostic workup based on the patient’s clinical presentation (28).

Because of the infrequent incidence of vulvar melanoma there has historically been a paucity of data to guide staging algorithms for patients with this disease. Recent data though support an assertion that AJCC staging guidelines (updated in 2010) for cutaneous melanoma should be applied to vulvar melanoma. Moxley et al. (34) examined 77 cases of vulvar melanoma from 5 academic medical centers, applying the 2002 modifications of the AJCC staging system for cutaneous melanoma, Breslow thickness and Clark level to all patients. Breslow’s thickness was associated with recurrence (p = 0.002) but not survival; however, the AJCC-2002 staging system was predictive of overall survival (p = 0.006) in patients with vulvar melanoma (34). It is important to emphasize that primary tumor thickness (using Breslow’s method) and nodal status are the primary determinants of survival in this disease. Also important, however, are the presence or absence of ulceration and mitotic rate; these descriptors also factor prominently in the staging of cutaneous melanoma (Table 19.3).

PATHOLOGY

Most vulvar malignancies arise within squamous epithelium. Although the vulva does not have an identifiable transformation zone, as the cervix does, squamous neoplasms arise most commonly on the labia minora, clitoris, posterior fourchette, perineal body, or medial aspects of the labia majora. Within the vulvar vestibule and fourchette, squamous neoplasia may arise where keratinized stratified squamous epithelium transitions to the nonkeratinized squamous mucosa of the vestibule, also known as Hart’s line (35).

Most vulvar squamous carcinomas arise within areas of epithelium associated with a recognizable epithelial cell abnormality. Approximately 60% of cases have adjacent HSIL (VIN 3). In cases of superficially invasive squamous carcinoma of the vulva, the frequency of adjacent HSIL (VIN 3) approaches 85% (36). Lichen sclerosis, usually with associated hyperplastic features, and/or HSIL (VIN 3), can be found adjacent to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma in 15% to 40% of the cases (37, 38). Granulomatous disease is also associated with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma; however, this is not a commonly associated finding in the United States. Thus, vulvar squamous cell carcinoma precursors can be considered in distinct groups: those associated with HPV, “usual” VIN, and those that are not (e.g., those associated with LS, chronic granulomatous disease) (see Epidemiology section).

Epithelial Carcinomas

Squamous Cell Carcinomas

The term microinvasive carcinoma is not recognized as meaningful in reference to vulvar cancer because there are no commonly agreed on pathologic criteria established for this term. The recent CAP-ASCCP terminology committee on Lower Anogenital tract terminology (the LAST committee) stated that the descriptor “superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma” be defined as stage IA carcinoma, and that the term “microinvasive carcinoma” not be used in reference to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree