RUSSELL K. PORTENOY  BROOKE SQUILLACE

BROOKE SQUILLACE  PAULINE LESAGE

PAULINE LESAGE

The heterogeneous patient population managed by gynecologic oncologists presents a broad range of problems in pain management. The incidence of cancer pain varies, depending on the type of neoplasm, stage, and extent of spread. Acute pains are highly prevalent, including the rather straightforward incisional pain that follows surgical procedures. Chronic pain occurs in the context of numerous other physical and psychosocial symptoms, often in the population with advanced disease. Effective relief of pain may improve mood, coping, function, and other aspects of quality of life. Gynecologic oncologists have the opportunity and obligation to effectively treat pain.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Pain is highly prevalent in the cancer population. Overall, 30% to 50% of patients undergoing active antineoplastic therapy and 75% to 90% of those with advanced disease experience chronic pain severe enough to warrant therapy (1–3). Although data specific to gynecologic tumors are meager, those extant suggest that the overall prevalence rates mirror these averages (1,4–6).

A survey of patients with ovarian cancer illustrates the prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain in this population (6). The sample included 111 inpatients and 40 outpatients. The median age was 55 years (range, 23 to 86 years), and most patients (82%) had stage III or IV disease at presentation and active disease (69%) at the time of the survey. Forty-two percent (n = 63) reported “persistent or frequent pain” during the preceding 2 weeks. This pain had a median duration of 2 weeks (range, <1 to 756 weeks) and was usually abdominal/pelvic (80%), frequent or almost constant (66%), and moderate to severe. Most patients reported that pain caused moderate or greater interference with various aspects of function, particularly activity (68%), mood (62%), work (62%), and overall enjoyment of life (61%). In a study of 97 outpatients with breast cancer (54% metastatic disease), 47% of patients experienced cancer-related pain substantially interfering with their mood, quality of life, and functional status. The most prevalent underlying pathology was postmastectomy syndrome (56%), followed by pain from bone metastasis (26%).

Tissue injury related to the neoplasm itself is the most common cause of chronic cancer pain. Pain prevalence increases with the extent of disease and can be as high as 90% among populations with advanced illness (7). Chronic pain also may be related to an antineoplastic treatment, such as surgery (8–10), and in a small minority of patients, pain is unrelated to either the malignancy or its treatment.

Observational studies suggest that satisfactory relief of chronic pain is possible in 70% to 90% of patients with cancer (11–14). However, undertreatment remains a serious problem, however (15–19), despite the availability of well-accepted guidelines for pain management (20). It has been suggested that an average of 43% of cancer patients receive inappropriate care for pain (21). Many concerns may undermine optimal treatment, among which are the underreporting of symptoms or nonadherence of patients, and the inadequate assessment, knowledge, or communication of health professionals (22).

Although the prevalence of severe acute pain in patients with gynecologic cancers has not been determined, and is likely changing with the increasing use of minimally invasive procedures, it is nonetheless presumed to be common and potentially controllable in a very large majority of cases. As more cancer surgeries are performed in the ambulatory setting, the ability to provide adequate treatment in unmonitored settings has become a greater challenge.

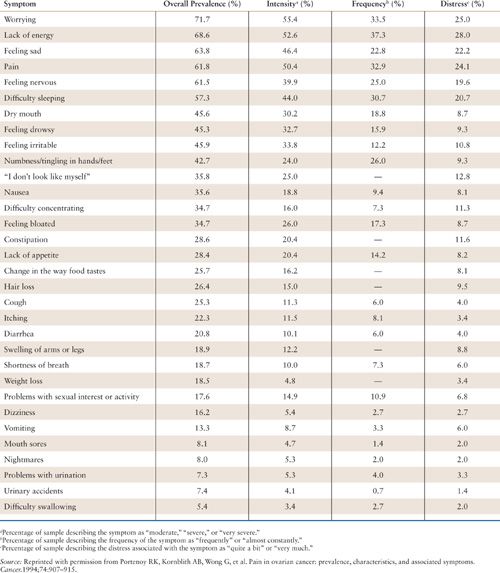

Patients with cancer, particularly those with advanced disease, also experience numerous symptoms other than pain. The most common of these symptoms are fatigue and anxiety or depression. Acute treatment-related symptoms, such as chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, also are prevalent. In the aforementioned survey of patients with ovarian cancer, the median number of symptoms per patient was 9 (range, 0 to 25) (Table 31.1) (6). In addition to pain, the most prevalent symptoms were fatigue (“lack of energy”), psychologic distress (“worrying,” “feeling sad,” and “feeling nervous”), and insomnia (“difficulty sleeping”). All of these symptoms had a prevalence of greater than 50%. Compared to norms, approximately one-third of the patients in this survey recorded heightened psychologic distress. The most important predictor of heightened distress was progressive impairment in physical functioning. Distress also can be worsened by psychological or social factors, or by spiritual or existential challenges (21).

Fatigue is one of the most common complications of cancer and its treatment, and exemplifies the problem of concurrent symptoms in the patient with significant pain. In a recent analysis, patients perceived fatigue to be the most distressing symptom adversely affecting quality of life (23). A definition proposed for the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision–Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) stresses the multidimensional nature of the phenomenon (24) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2011 guidelines identified 8 factors that should be assessed as potential causes of prolonged fatigue, one of which is pain (others include medications/side effects, emotional distress, sleep disturbance, anemia, nutrition, decreased functional status, and other comorbidities) (25). Patients with pain should be evaluated for meaningful concomitant symptoms, and the assessment of other symptoms should prompt an assessment of pain.

Prevalence and Characteristics of Symptoms Associated with Ovarian Cancer (n = 151) |

ASSESSMENT OF CANCER PAIN

The assessment of chronic pain in patients with gynecologic cancer requires an understanding of its phenomenology, pathophysiology, and syndromes. Optimally, this assessment must also consider the broad range of physical, psychologic, and social disturbances concurrently experienced by these patients. Patients with acute pain, particularly acute postoperative pain, pose less complex management problems, but could still potentially benefit from an ongoing comprehensive assessment. The patient’s description of the pain, findings on physical examination, objective data from imaging and other tests, and information about the extent of the malignant disease and its treatment are all utilized to assess the likely etiology and underlying pathophysiology of the pain, and if possible, identify a specific cancer syndrome (26).

National medical organizations have developed guidelines in an effort to more effectively detect and monitor pain. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations developed a standard requiring that pain be assessed initially and periodically in all hospitalized patients. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2011 Adult Cancer Pain Guidelines require a formal pain assessment, measurement of pain intensity, reassessment of pain intensity at specific intervals, psychosocial support, and specific educational material (25).

Definition of Pain

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (27). Reported pain may be perceived by the clinician to be greater than or less than the observable degree of tissue injury. In the cancer population, a physical process capable of explaining the pain can usually be identified, but this does not obviate the need for a careful assessment of other factors, including psychologic disturbances, that could be influencing the intensity of the pain or contributing to pain-related distress.

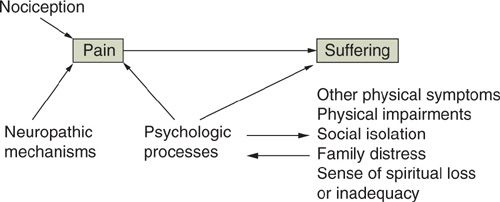

The definition of pain can be further clarified by the distinctions among nociception, pain, and suffering (Fig. 31.1) (28). Nociception is the activity produced in the afferent nervous system by potentially tissue-damaging stimuli. Clinically, nociception is inferred to exist whenever tissue damage is identified. Pain is the perception of nociception and, like other perceptions, can be determined by more than the activity in the sensorineural apparatus alone. Although tissue damage related to the tumor or its treatment is common in those with cancer pain, a careful assessment is needed to infer the degree to which the pain report is consistent with the nociception presumed by the clinician on the basis of the physical findings. In all cases, factors other than nociception, including neuropathic processes that can sustain pain in the absence of ongoing tissue injury (see below) and psychologic disturbances, must be evaluated as other potential determinants of the pain. The failure to address these other factors while targeting therapy at the sources of nociception can lead to a poor outcome in which the focus of tissue damage is ameliorated but the pain continues.

FIGURE 31.1. Distinctions and interactions between nociception, pain, and suffering.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Portenoy RK. Cancer pain: pathophysiology and syndromes. Lancet. 1992;339:1026–1031.

Suffering, or “total pain,” can be defined as a more global aversive experience determined by numerous perceptions, one of which may be pain (see below). Among the many other factors that may contribute to suffering are the perception of physical deterioration, the experience of symptoms other than pain, psychologic disturbances (e.g., depression or anxiety), disruption in the family, social isolation, and fear of death. Just as an inordinate focus on nociception, rather than pain, can lead to interventions that reduce tissue damage without alleviating symptoms, an emphasis on pain management alone in patients with profound suffering determined by other factors can fail to influence favorably the overall quality of life even if physical comfort is enhanced (29,30).

Evaluation of the Pain Complaint

The comprehensive assessment of pain should include information about temporal characteristics (onset and duration), course (stable or changing since onset, relatively constant or widely fluctuating), severity (both average and worst), location, quality, and provocative and palliative factors. This evaluation is complemented by information about the patient’s extent of disease, related medical and psychosocial conditions, present and past pain management strategies and their outcomes, the impact of the pain on the patient’s daily life and functioning, as well as the patient’s and family’s knowledge of, expectations about, and goals for pain management. Risk factors for the undertreatment of the patient’s cancer pain and risk factors for serious physical or psychiatric comorbidities (such as drug abuse) should also be examined.

Characteristics of Pain

Intensity. The measurement and recording of pain intensity is an essential element in the comprehensive assessment of pain. Although more information than intensity alone is needed to understand and manage cancer pain, a systematic method for assessing intensity is foundational. The most common approaches are a verbal rating scale (none, mild, moderate, severe, excruciating) and/or an 11-point numeric scale (where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain imaginable). A visual analog scale (VAS) that uses a 10-cm line anchored at one end by the words “no pain” or “least possible pain” and at the other end by “worst possible pain” is another simple and valid approach to pain measurement. The choice of scale is less important than consistency in its use over time. Brief assessment tools modeled on this approach also can be applied to the intensity measurement of nonpain symptoms, such as depression and fatigue.

Multidimensional scales are available, but usually are utilized in research settings. These scales provide a more comprehensive measure of the pain experience, often encompassing such factors as function and quality of life.

Temporal. Acute pain usually has a well-defined onset and a readily identifiable cause (e.g., surgical incision). It may be associated with anxiety, overt pain behaviors (moaning or grimacing), and signs of sympathetic hyperactivity (including tachycardia, hypertension, and diaphoresis). In contrast, chronic pain is characterized by an ill-defined onset and a prolonged, fluctuating course. Overt pain behaviors and sympathetic hyperactivity are typically absent, and vegetative signs, including lassitude, sleep disturbance, and anorexia, may be present. A clinical depression evolves in some patients. Most patients with chronic cancer pain also experience periodic flares of pain, or “breakthrough pain,” an observation with important therapeutic implications (see below).

Topographic. The distinctions among focal, multifocal, and generalized pains may influence both the assessment and treatment of the patient. Some therapies, such as nerve blocks and cordotomy, depend on the specific location and extent of the pain.

The distinction between focal and referred pain is similarly important. Focal pains are experienced superficial to the underlying nociceptive lesion, whereas referred pains are experienced at a site distant from the nociceptive lesion.

Pain may be referred from a lesion involving any of a large group of structures, including nerve, bone, muscle, or other soft tissue, and viscera (31–33). Various subtypes can be distinguished: (a) pain referred anywhere along the course of an injured peripheral nerve (such as pain in the thigh or knee from a lumbar plexus lesion); (b) pain referred along a course of the nerve supplied by a damaged nerve root (known as radicular pain); (c) pain referred to the lower part of the body, usually the feet and legs, from a lesion involving the spinal cord (called funicular pain); and (d) pain referred to a site remote from the nociceptive lesion and outside the dermatome affected by the lesion (e.g., shoulder pain from diaphragmatic irritation). Knowledge of pain referral patterns is needed in order to target appropriate assessment procedures. For example, a patient with recurrent cervical cancer who reports progressive pain in the inguinal region may require evaluation of numerous structures to identify the underlying nociceptive lesion, including the subjacent pelvic bones and hip joint, pelvic sidewall, paraspinal gutter at an upper lumbar spinal level, and intraspinal region at the upper lumbar level.

Etiology

The etiology of acute pain is usually clear-cut. Further evaluation to determine the underlying lesion or pathophysiology of the pain is not indicated unless the course varies from the expected. In contrast, the etiology of chronic cancer-related pain may be more difficult to characterize. In most cases, pain is due to direct invasion of pain-sensitive structures by the neoplasm (27,28,34). The structures most often involved are bone and neural tissue, but pain can also occur when there is an obstruction of hollow viscus, distention of organ capsules, distortion, or occlusion of blood vessels, and infiltration of soft tissues. The etiology of pain in less than a quarter of patients relates to an antineoplastic treatment, and less than 10% have pain unrelated to the neoplasm or its treatment (34).

These data suggest that a careful evaluation of cancer patients with pain is likely to identify an underlying nociceptive lesion, which will usually be neoplastic. A survey of patients referred to a pain service in a major cancer hospital noted that previously unsuspected lesions were identified in 63% of patients (35). This outcome altered the known extent of disease in virtually all patients, changed the prognosis for some, and provided an opportunity for a primary antineoplastic therapy in approximately 15%.

Pathophysiology

Pain is labeled nociceptive if it is inferred that the sustaining mechanisms involve ongoing tissue injury. This injury can involve either somatic or visceral structures. The quality of somatic nociceptive pain is typically described as aching, stabbing, throbbing, or pressure-like. The quality of visceral nociceptive pain is largely determined by the structures involved. Obstruction of hollow viscus is usually associated with complaints of gnawing or crampy pain, whereas injury to organ capsules or mesentery is associated with an aching or stabbing discomfort.

Pain is labeled neuropathic if the evaluation suggests that it is sustained by abnormal somatosensory processing in the peripheral or the central nervous system (CNS) and there is some identifiable neurologic injury. Neuropathic mechanisms are involved in approximately 40% of cancer pain syndromes and can be disease-related (e.g., tumor invasion of nerve plexus) or treatment-related (e.g., postmastectomy syndrome, chemotherapy-induced painful polyneuropathy) (34). Among those with metastatic disease, neuropathic pain usually results from neoplastic injury to peripheral nerves. Other, less common subtypes include (a) those in which the focus of activity is in the CNS (sometimes generically termed deafferentation pain); and (b) those in which the pain is believed to be maintained by efferent activity in the sympathetic nervous system (so-called sympathetically maintained pain). Identification of a neuropathic mechanism is extremely important in clinical management because specific therapies may be useful for these conditions (see below).

Neuropathic pain is diagnosed on the basis of the patient’s verbal description of the pain and evidence of injury to neural tissue. Patients may use any of a variety of verbal descriptors but some, such as “burning,” “shock-like,” or “electrical,” are particularly suggestive of neuropathic pain (36,37). Areas of abnormal sensations are often found on physical examination. These may include hypesthesia (a numbness or lessening of feeling), paresthesias (abnormal nonpainful sensations such as tingling, cold, or itching), hyperalgesia (increased perception of painful stimuli), hyperpathia (exaggerated pain response), and allodynia (pain induced by nonpainful stimuli such as a light touch or cool air).

Although pain can occur as a primary outcome of psychologic processes, labeled in psychiatric parlance as one of the somatoform disorders, this appears to be rare in the cancer population. Nonetheless, psychologic factors may augment or alter the pain complaint, and not surprisingly, pain may be associated with fluctuations in psychologic distress. In one series of 203 inpatients with cancer, for example, depression was independently associated with pain intensity after controlling for performance status, disease status, and perceived treatment effect (38).

To assess the complex relationship between pain and psychiatric disease, it is useful to have familiarity with the common disorders that are present in gynecologic malignancies. One study observed major depression in nearly one quarter of women hospitalized with cervical, endometrial, and vaginal cancer (39), and another reported more severe depression and poorer body image among gynecologic patients than those with breast cancer undergoing mastectomy (40).

If the assessment of the pain does not provide enough information to categorize it as primarily nociceptive or neuropathic, or mixed, or yield a sufficient understanding of the psychologic factors that may be influencing the pain, it is important to acknowledge this lack of certainty and avoid labeling the patient with a term that may inappropriately direct care. The greatest concern in this regard is the labeling of pain as psychogenic when the assessment does not yield positive evidence of a psychiatric disorder, but an alternative answer is lacking. In this case, it is better to label the pain idiopathic than to speculate about underlying factors that are not clearly demonstrable from the evaluation.

Pain Syndromes

Efforts to improve the assessment of cancer pain have been greatly encouraged by the description of numerous pain syndromes, each of which is defined by a cluster of symptoms and signs (Table 31.2) (27,28,34,41,42). Syndrome identification can help direct the diagnostic evaluation, clarify the prognosis, and target therapeutic interventions. Recognition of pain syndromes that occur commonly among patients with gynecologic cancers (Table 31.3) can also facilitate the assessment of these patients.

Cancer Pain Syndromes |

I. Pain associated with direct tumor involvement

A. Due to invasion of bone

1. Base of skull

2. Vertebral body

3. Generalized bone pain

B. Due to invasion of nerves

1. Peripheral nerve syndromes

2. Painful polyneuropathy

3. Leptomeningeal metastases

4. Epidural spinal cord compression

C. Due to invasion of viscera

D. Due to invasion of blood vessels

E. Due to invasion of mucous membranes

II. Pain associated with cancer therapy

A. Postoperative pain syndromes

1. Postthoracotomy syndrome

2. Postmastectomy syndrome

3. Postradical neck dissection

4. Postamputation syndromes

B. Postchemotherapy pain syndromes

1. Painful polyneuropathy

2. Aseptic necrosis of bone

3. Steroid pseudorheumatism

4. Mucositis

C. Postirradiation pain syndromes

1. Radiation fibrosis of brachial or lumbosacral plexus

2. Radiation myelopathy

3. Radiation-induced peripheral nerve tumors

4. Mucositis

III. Pain indirectly related or unrelated to cancer

A. Myofascial pains

B. Postherpetic neuralgia

C. Chronic headache syndromes

Pain Syndromes Commonly Encountered among Patients with Gynecologic Cancer |

Acute Pain Syndromes

At any stage of disease:

Postoperative pain

Mucositis

In advanced stages of disease:

Recurrent bowel obstruction

Ureteral obstruction

Movement-related pain in brachial/lumbosacral plexopathy

Movement-related pain from bony lesions

Cancer-Related Chronic Pain Syndromes

Brachial/lumbosacral plexopathy

Chronic abdominal pain: bowel obstruction, ascites, hepatomegaly

Tenesmoid pain

Bone pain from metastases

Treatment-Related Chronic Pain Syndromes

Postmastectomy syndrome

Radiation-induced plexopathy

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (paclitaxel, cisplatin)

Comprehensive Assessment

A comprehensive assessment that incorporates this pain-related information can be used to elaborate a problem list that guides the priorities and direction of therapy. In many situations, such as acute postoperative pain or chronic pain related to a well-characterized lesion (e.g., pathologic fracture), the assessment issues are simple and the problem list is brief and straightforward. In other cases, most often in populations with advanced disease, a complex group of symptoms, medical disorders, and psychosocial disturbances greatly complicate the assessment process. In these cases, a comprehensive assessment encourages efficient selection of an appropriate multimodal therapy.

The biopsychosocial model implied by this clinical reality has provided a framework for pain research. A consensus has been reached that the core outcome domains for studies of chronic pain are pain intensity, physical functioning, emotional functioning, participant ratings of improvement and satisfaction with treatment, and other symptoms and adverse events (43).

Patients whose pain had been responsive to pain medication but experience an increase in pain intensity or a change in pain characteristics should be comprehensively reassessed as the initial step in management. The goal is to determine whether specific factors responsible for the change can be identified. Relapse or disease progression, for example, may be amenable to primary therapeutic strategies, such as chemotherapy to address disease progression associated with loss of analgesic effectiveness. Other factors, such as cord compression, systemic or local infection, and psychologic distress (e.g., depression), also may be treatable.

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE PAIN

Although the treatment of patients with acute pain, particularly postoperative pain, is typically less challenging than the long-term management of chronic pain, the outcomes achieved in routine practice settings are often inadequate. Given the potential efficacy of widely used strategies, such as patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), less-than-satisfactory outcomes may be more related to systems issues, such as access to a pain service or prolonged pharmacy preparation times, than purely clinical issues. Cancer patients also commonly have concurrent medical problems, psychologic disturbances, and prior and current drug exposures that may increase the heterogeneity of the population and diminish the likelihood that routine measures provide adequate relief of pain. The need for clinicians and administrators to attend to the problem of acute pain and provide the resources and systems for expert management is therefore particularly important in this population.

“Routine” Approach to Postoperative Pain

Despite great variability in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of single opioid doses (44), and the large proportion of patients who fail to attain adequate analgesia with routine postoperative care, many patients do respond adequately to an opioid, traditionally morphine or meperidine, administered “as needed.” In the cancer population, the starting dose must take into account the prior opioid exposure of the patient. A reasonable starting dose for morphine in opioid-naïve patients, for example, would be 5 to 8 mg every 3 hours as needed, or 1 mg every 6 minutes as needed if a PCA device is used. If the patient has a history of current opioid use for pain, a reasonable starting dose would be the equivalent of 5% to 10% of the total opioid consumption during the previous 24 hours. If the drug or route of administration is changed, an equianalgesic dose table must be consulted to calculate the equivalent total daily dose of the new drug. Once a dose is selected, it can be initially administered every 3 hours as needed. If repetitive dosing is employed, and the dose or interval selected initially is not effective after the first or second dose, an increase in the dose or shortening of the dosing interval should be considered.

As-needed dosing of this type usually is most effective when a procedure is likely to yield pain for a short while. In these cases, the use of an opioid with a short half-life, such as morphine or hydromorphone is preferred; meperidine, although likely to be well tolerated during brief therapy, is generally not preferred because of the availability of safer drugs (see below). The use of the intravenous route through slow injection or brief infusion will reduce distress associated with painful injections.

The proportion of cancer patients with postoperative pain who will be undertreated by an as-needed dosing schedule can be diminished if several factors are recognized. Most important, titration may be needed. The variability in analgesic requirements may require changes in the starting dose, adjustment in the dosing interval during the immediate postoperative period, or both. Some patients require several dose adjustments. Similarly, variability in pain duration after any particular operation is great and the duration of opioid treatment must be flexible and be determined solely by patient response. Some patients have concerns about opioid-induced side effects and addiction, which may augment distress and diminish patient compliance with therapy unless strong reassurance is provided by the physician and other staff.

In some populations, the routine approach to postoperative pain management can be enhanced by the use of a nonopioid analgesic, specifically a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). In the United States, ketorolac, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen all have been approved for short-term parenteral use. In opioid-naïve patients, a standard dose of ketorolac can provide analgesia equivalent to a parenteral dose of morphine of 10 mg (45). The addition of intravenous ketoprofen (not approved in the United States) to intravenous PCA with tramadol after major gynecologic cancer surgery was shown to significantly reduce opioid consumption (46). At the present time in the United States, patients who are highly predisposed to opioid side effects or toxicity, such as those with severe preexisting lung disease, may benefit from a trial of one of the intravenous nonopioid analgesics, either in lieu of opioid therapy or in combination with an opioid. Ketorolac and ibuprofen should not be used when NSAID treatment is contraindicated.

Patient-Controlled Analgesia

PCA has achieved great popularity in the management of postoperative pain and there is strong evidence that it improves analgesia, decreases the risk of pulmonary complications, and increases patient satisfaction when compared to conventional opioid analgesia (47). Theoretically, the self-administration of small doses on a frequent basis allows the patient to tailor the dose to the pain and enhance a sense of personal control while achieving a more stable plasma drug concentration. However, not all studies of this modality have been positive. For example, a randomized, controlled trial of 227 gynecologic cancer patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery found that patients who were switched from parenteral to oral morphine on the first postoperative day experienced the same degree of pain control as those who received parenteral morphine via PCA pump (48). The latter studies suggest that careful attention to dosing rather than the availability of a pump per se is the key factor in achieving adequate pain control.

Other Approaches to Acute Pain Management

Numerous alternative approaches to postoperative pain management have been explored. Some require the expertise of pain specialists.

Preemptive Analgesia

The administration of an analgesic prior to surgical tissue injury may reduce postoperative pain and opioid requirements, and possibly have longer-term benefits (49). There are conflicting data, however, and the influence of type of analgesia, timing, and range of outcomes has not been elucidated. The role of this strategy in gynecologic surgery is unclear and it is not generally pursued.

Oral Pretreatment and Postoperative Combination Therapy

Pretreatment with sustained-release morphine or oxycodone reduces postoperative pain and analgesia requirements (50,51). This technique is seldom used, but may be an option in patients whose postoperative pain management is expected to be problematic.

Presurgical or postsurgical addition of an NSAID in combination with an opioid can augment analgesia and reduce the use of opioids, potentially leading to reduction of opioid side effects. A recent controlled trial, for example, demonstrated that postoperative celecoxib improved outcomes and was well tolerated in patients undergoing laparascopic surgery (52). Equally important, there is now substantial data demonstrating that the combination of an opioid and gabapentin, a neuronal calcium channel modulator widely used for the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain, improves a range of outcomes in diverse surgeries, including hysterectomy (53).

Intraspinal Analgesia

Epidural analgesia is now common practice in many hospitals. There is strong evidence that analgesia is better with this approach than with parenteral opioids (54–57). There may also be a lower risk of some postoperative complications (58,59). Some studies suggest benefits that are prolonged into the recovery phase after surgery, but the extant data are insufficient to judge these benefits adequately (55). Some side effects are more likely to occur with this technique than with conventional systemic opioid therapy, including pruritus and hypotension; resources, including staff with special competencies, are needed to implement the approach safely.

Given the abundant evidence of better analgesia and related outcomes, patients undergoing major gynecologic surgery should be considered for epidural analgesia if the resources exist to provide it. Although there is less clinical experience in the use of subarachnoid opioid administration for postoperative pain, the technique can also provide excellent relief (60–62).

Regional Anesthetic Techniques

There are numerous regional anesthetic techniques that may be useful for the management of acute pain. The simplest is the application of local anesthetic at the surgical site. Topical anesthetics that are longer acting are in development and may offer substantial benefits in the future.

Neural blockade capable of denervating the painful site is a potential approach in most cases. Catheters that deliver local anesthetic at a dose high enough to produce a sensory block can be placed in the epidural space or along peripheral nerves or plexus. Regional anesthesia can be used during an operation and then continued into the postoperative setting for pain control. For example, a recent study demonstrated that subarachnoid block for vaginal hysterectomy yielded significantly better immediate postoperative analgesia versus standard general anesthesia (63).

Other Approaches

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has been suggested to be a useful modality for incisional pain after abdominal surgery (64). Despite the evident simplicity and safety of the approach, there has been little application of its potential.

Cognitive approaches, including stress reduction, relaxation, hypnosis, and distraction techniques, have also reduced postoperative pain and analgesic requirements (65,66). These techniques are labor intensive and are almost never sufficient as the sole means of analgesia. Nonetheless, studies have established that higher levels of anxiety and depression can negatively influence postoperative pain and analgesic requirements (67), and efforts to reduce anxiety through preoperative education and postoperative psychologic interventions are likely to have salutary effects.

MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC CANCER PAIN

The successful management of acute postoperative pain is an important concern of the gynecologic oncologist, and optimal pain management should be considered a standard of care. The treatment of chronic pain is a far more challenging problem, particularly among those with advanced illness.

Cancer Pain, Symptom Distress, and Palliative Care

Most cancer patients who experience chronic pain also develop other physical and psychologic symptoms. Pain, fatigue, and psychologic distress are the most prevalent symptoms across populations (68,69). A broad assessment of symptom distress, followed by concurrent therapy of the most problematic symptoms other than pain, is a fundamental aspect of pain management.

Symptom distress, in turn, is only one aspect of the multifaceted problem of suffering (29,30,70). The assessment of suffering requires an evaluation in multiple domains, including the physical, psychologic, social, and spiritual. This in turn requires open and ongoing communication between the clinician and the patient.

The assessment and management of problems that relate to the broad constructs of suffering and quality of life are part of the therapeutic model of palliative care, which focuses on all patients with serious or life-threatening illness and their families. This therapeutic approach aims to reduce illness burden and enhance the quality of life of the patient and family throughout the course of the disease. In the United States, palliative care is rapidly evolving. Specialist care now has a well-defined purview, as codified in a consensus document published by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (71). The American Board of Medical Specialties approved Hospice and Palliative Medicine as a formal subspecialty, and in an unprecedented event, ten separate primary boards are cosponsoring, including the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Specialist care is now being provided by institution-based palliative care programs, which now exist in almost 70% of U.S. hospitals with 50 beds or more. Specialist care in the setting of advanced illness is provided through more than 5,000 hospice agencies in the United States.

Specialist-level palliative care is provided by interdisciplinary teams, each member of which has special competencies. In addition to the board certification for physicians, nurses, and social workers are able to obtain certificates that confirm special knowledge and skills.

In contrast to specialist-level care, generalist-level palliative care should be considered a best practice for oncologists and others involved in the day-to-day management of patients with a serious illness such as a gynecologic cancer. Physicians must understand the necessity of palliative care, that is, interventions that may reduce illness burden or maintain quality of life, from the time of diagnosis onward. They must acknowledge the multidimensional nature of this endeavor, including a focus on communicating well, setting goals, coordinating care, sharing decision making, promoting advance care planning, managing symptoms, providing psychosocial and spiritual support, addressing practical needs in the home, assisting the family as needed, and dealing with the challenges of end-of-life care when this is necessary. Referral to specialist services to address complex needs, or provide hospice home care services, is central to the role of the generalist.

General Principles of Pain Management

The development of a successful strategy for pain management must consider the etiology and pathophysiology of pain, the patient’s medical status, and the goals of care. Although the main approach for the management of cancer pain is opioid-based pharmacotherapy, other interventions, including disease-oriented treatments (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation) or other analgesic techniques, may be appropriate in selected cases.

Role of Primary Therapies

Effective treatment of the pathology underlying the pain can be analgesic (72,73). Primary treatment includes antineoplastic therapies and interventions directed at specific structural pathologies (e.g., lysis of adhesions). There is evidence in a limited number of cancers that specific chemotherapy regimens yield analgesic effects and it is a common observation that patients who attain a partial or complete response also experience improved symptoms. In a study of patients with metastatic breast cancer, for example, palliative chemotherapy with doxorubicin with or without vinorelbine resulted in an improvement of pain in 60.4% of the 111 patients who suffered from pain at baseline (74); although patients with an objective tumor response were more likely to have an improvement in pain (84.9%), fully 61% of patients with stable disease also benefited. In a small study of patients with advanced ovarian cancer, palliative chemotherapy was associated with improvement in symptom control, emotional well-being, and global quality of life (75). In a study of patients with recurrent/advanced cervical cancer, 67% of patients experienced improvement of pain after alternating treatment with PBM (platinum, bleomycin, and methotrexate) and PFU (platinum and 5-fluorouracil [5-FU]) (76).

Radiation therapy commonly is used to manage pain and there is evidence that it can provide effective and durable palliation of pain and other symptoms in chemotherapy-refractory patients with ovarian cancer (77,78) and cervical cancer (79). Radiation therapy can also provide analgesia to as many as 80% of those treated for bone metastases (80). Patients with widespread bone metastasis or bone pain refractory to local field radiotherapy may benefit from treatment with radiopharmaceuticals, such as strontium 89 or samarium-153 (81). In addition, analgesia may be an expected result when radiation is used to treat epidural disease, tumor ulceration, cerebral metastases, superior vena cava obstruction, and bronchial obstruction.

Unfortunately, many patients with chronic cancer pain have no option for primary antineoplastic therapy or did not benefit when it was provided. The approach to these patients involves a diverse group of primary analgesic treatments (Table 31.4). Several concurrent interventions are often required to manage the pain. The benefits of analgesic therapies must be balanced against the side effects they produce in a way that optimizes the outcome for the patient. Repeated assessments, performed as part of a broader approach to palliative care, are essential in this process and often lead to adjustments in the therapy.

THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES: PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

Prospective trials indicate that more than 70% of patients can achieve adequate relief of cancer pain using a pharmacologic approach (3,12–14). Effective pain management requires expertise in the administration of 3 groups of analgesic medications: NSAIDs, opioid analgesics, and adjuvant analgesics. The term adjuvant analgesic is applied to a diverse group of drugs that have primary indications other than pain but can be effective analgesics in specific circumstances, such as in the treatment of neuropathic pain.

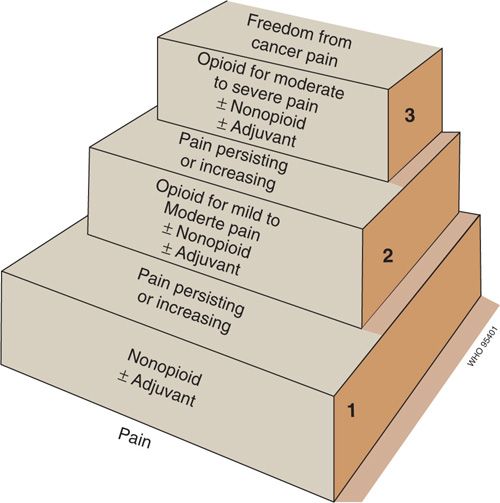

A model approach to the selection of these drugs, known as the “analgesic ladder,” was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the 1980s and remains influential today (Fig. 31.2) (3). According to this approach, patients with mild to moderate cancer-related pain are first treated with acetaminophen or an NSAID. This drug is combined with an adjuvant drug that can be selected either to provide additional analgesia (i.e., an adjuvant analgesic) or to treat a side effect of the analgesic or a coexisting symptom. Patients who present with moderate to severe pain, or who do not achieve adequate relief after a trial of an NSAID, should be treated with an opioid conventionally used to treat pain of this intensity (previously designated a “weak” opioid), which is typically combined with an NSAID and may be administered with an adjuvant if there is an indication for one. Those who present with severe pain or who do not achieve adequate relief following appropriate administration of drugs on the second rung of the analgesic ladder should receive an opioid conventionally used for severe pain (previously called a “strong” opioid), which may be combined with an NSAID or an adjuvant drug as indicated.

Approaches Used in the Management of Chronic Cancer |

PAIN

Primary therapies

Radiation therapy

Chemotherapy

Surgery

Antibiotics

Primary analgesic therapies

Pharmacologic approaches

Interventional approaches

Physiatric approaches

Neurostimulatory approaches

Psychologic approaches

Complementary and alternative medicine approaches

FIGURE 31.2. The 3-step “analgesic ladder” proposed by an expert committee of the Cancer Unit of the World Health Organization.

Source: Reproduced with permission from the World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996.

The analgesic ladder is important historically and is still widely cited in the developing world in an effort to encourage policy makers to expand medical access to opioid drugs. It is a limited clinical guideline in most developed countries, where access to numerous opioid formulations and other analgesic modalities has influenced clinical practice. Nonetheless, the fundamental concept promoted by the analgesic ladder model—opioid therapy on a long-term basis should be considered the mainstay for the therapy of chronic moderate to severe cancer-related pain—remains widely accepted and a very important message of the original paradigm.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

In the United States, the nonopioid analgesics comprise acetaminophen and the NSAIDs (Table 31.5). These drugs have a well-established role in the treatment of cancer pain (82–85). Based on clinical observations, NSAIDs appear to be especially useful in patients with bone pain or pain related to grossly inflammatory lesions, and relatively less useful in patients with neuropathic pain (86). In addition, NSAIDs have an opioid-sparing effect that may be helpful to prevent the occurrence of dose-related side effects (87,88).

NSAIDs inhibit the enzyme cyclo-oxygenase (COX) to reduce production of peripheral and central prostaglandins, and this action presumably underlies their analgesic effects. There are multiple forms of COX. COX-1 is relatively more constitutive, physiologically active in many tissues, and COX-2 is relatively inducible, produced as part of the inflammatory cascade. Compounds that are more selective for COX-2 than COX-1 have a lower risk of inducing gastrointestinal adverse effects (89,90), and some drugs that are relatively COX-2 selective have been labeled in this way and promoted for their enhanced gastrointestinal safety. In the United States, the only drug of the latter type now on the market is celecoxib. Rofecoxib and valdecoxib were previously available, but were taken off the market due to concerns related to cardiovascular safety.

The clinical decision to offer a NSAID to a patient with cancer usually hinges on the assessment of drug-related risk. Gastrointestinal toxicity is well recognized, and in recent years, cardiovascular safety has become a prominent concern. Based on numerous studies, it is most reasonable to conclude that all NSAIDs are prothrombotic and pose an increased risk of peripheral vascular disease, myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attacks, and stroke (91,92). Mechanistically, this risk is associated with COX-2 inhibition, whether produced by the nonselective COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors or by the COX-2 selective drugs. Although the risk varies across drugs, large comparative studies have been retrospective and results have been conflicting. In the United States, all NSAIDs now have a boxed warning in the package insert, which offer cautions about both gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk. Among all commercially available NSAIDs, naproxen generally is viewed as having the lowest risk of cardiovascular toxicity.

Although all NSAIDs have the potential to produce adverse gastrointestinal effects, ranging from pain or nausea to frank ulceration and hemorrhage, there are important drug-selective differences. The COX-2 selective agents, such as celecoxib, are less likely to cause these effects, as are several of the so-called nonselective agents, such as ibuprofen and diclofenac. Coadministration of a proton pump inhibitor, such as omeprazole or misoprostol, also should be considered to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal damage induced by NSAIDs (93).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree