17 Violence against women

Rape

What is the difference between rape and sexual assault?

To most people, adult sexual assault equals rape. Rape is a legal term, however, not medical. Two elements are involved in its definition: sexual intercourse and commission of the act forcibly and without consent.1 Adult sexual assault is a broader term, defined as occurrences of a sexual nature that happen without a person’s consent. This definition includes events such as attempted rape, unwanted sexual advances from someone in authority, sexual advances from relatives, narrowly missing being sexually assaulted, and situations where there is violence or the threat of violence and at the same time fear of being sexually assaulted. All of these forms of sexual assault or threatened sexual assault are likely to have an effect on the victim.

When dealing with a topic such as rape, it is important that, as a GP, you recognise how you conceptualise sexual assault. In the past the attitude has been one of blaming the victim, that men cannot possibly control their sexual urges and that if women dressed and acted more modestly, rape would not occur. This mentality is characterised by the notion that ‘No’ doesn’t necessarily mean ‘No’ and that if a woman asks a man into her home it is an invitation and permit for him to have sex with her. With the rise of feminism, our understanding of rape has come a long way. Sexual assault is typically an issue not of sexual motivation but of power and control. Assailants display anger, violence, hostility and aggression.2 Their power over the victim is more satisfying than the actual sexual act.3

How common is sexual assault?

The true prevalence of adult sexual assault is difficult to ascertain because it is often not reported to police. Indeed, one study4 reported that only 12% of rape victims and 7% of those sexually assaulted had reported these crimes to the police, indicating that official rates greatly underestimate their true prevalence. In the USA, it has been estimated that one in six women will be raped during her lifetime.5

Studies of community samples show that the lifetime prevalence of sexual assault ranges from 13.5%6 up to 59.9%, if all sexually stressful events (i.e. non-contact sexual assault) are considered.7

In studies of family practice patients,8 approximately 40% recalled some form of sexual aggression since the age of 18; 7.5% had been raped and 17% had experienced attempted rape. In another study that surveyed women attending general practitioners, 13% of women over the age of 18 answered that they had experienced rape or attempted rape at some time during their adult life.9

A sample of student patients found a higher prevalence of rape or attempted rape of 28.7%,8 consistent with the phenomenon of ‘date rape’,

which would be more prevalent in a student population. In this same study, almost half of the victimised individuals felt they would have great difficulty discussing their experience with a medical professional or would not be able to discuss it at all. This suggests that the same factors that discourage the reporting of sexual assault to official authorities also discourage communication with doctors.

What role should a GP have?

When responding to a disclosure of sexual assault, it is important to10:

Should only forensic doctors see rape victims?

Many GPs feel reluctant to take on the care of rape victims and try to pass on the job to forensic services. This is appropriate when the woman has decided to make a formal report to the police and where there is the likelihood of legal ramifications. Forensic services are often difficult to access, however, and many women do not want to be examined by a stranger, or indeed by a male doctor, in these circumstances. Other women prefer their own GPs to conduct the necessary examinations, and still others are unsure at the time of presentation whether they will actually proceed to make a report. It is therefore important that all GPs have the skills to undertake the care of victims of sexual assault in their own practice and feel confident to do so.

What special consideration should be taken?

Taking a history, conducting an examination and undertaking the management of a patient who has undergone a sexual assault differs in many ways from a routine consultation. For a start, the emotional needs of the woman are paramount. The attending GP must ensure that the interview and subsequent examination takes place in a quiet, safe and private environment. Patient consent must be sought at every step of the consultation: history taking, physical examination, evidence collecting and photographing. This will help establish trust and confidence between the GP and the patient, and help the patient to regain some control over her circumstances. Box 17.1 summarises the needs of a sexual assault survivor.

BOX 17.1 Needs of sexual assault survivors

Sexual assault survivors need:

How soon after the assault do women present?

The time when the patient is first seen in relation to the assault is highly variable. Sometimes women will present straight after they have been assaulted, but often there is a delay of days to weeks after the incident. This may be because of fear of retaliation, feeling too vulnerable to undergo ‘questioning’, or not wanting to be examined or ‘labelled’ as a rape victim. Often a woman will not present until friends or family members manage to convince her to report to authorities several days after the assault.

What key features of the history are important to document?

When taking a history from a woman who has been a victim/survivor of sexual assault, it is important to maintain a respectful and empathic attitude and to ask open-ended questions. Sometimes the patient may not be able to give a history or may have a friend or relative who tells part of the history if the woman is too upset. In these situations, it is important to record why the woman is unable to tell her story—for example she is too upset or crying uncontrollably. If others provide information, it is important to document this clearly. The issues listed in Box 17.2 should be covered and recorded in an objective fashion, as far as possible using the woman’s own words.

BOX 17.2 Important items to cover when taking a history from a woman who has been assaulted

How and when should a physical examination be carried out?

After a sexual assault women often feel very fearful of undergoing a physical examination. This is understandable, so it is important to make the woman feel as in control of the situation as possible and to offer her the choice of a female doctor, should she want one. She should also be able to have a friend or relative present, if she so desires. The patient should be prepared and explanations given before beginning any examination or procedure and before moving from examination of one area of the body to another.11

The purpose of the physical examination is twofold: to assess the patient for physical injuries; and to collect evidence for forensic evaluation and possible legal proceedings. Physical examination and evidence collecting are therefore done congruently.

Valuable evidence may be gathered from clothing that a woman was wearing at the time of the assault. Clothing can be collected up to 1 month after the incident, provided the items have not been laundered. Only the victim should handle her clothes. Items of clothing should be placed in paper bags, not plastic bags, since plastic may promote bacterial growth on blood or semen stains.12

The examination should then proceed in an orderly fashion, with non-threatening areas examined first in order to build trust and confidence. The presence of foreign bodies such as soil or grass should be noted as well as any injuries. The scalp, ears, face (nose, eyes, cheeks and lips) and mouth (tongue, throat, palate and teeth) are examined. Traumatic asphyxiation from choking may result in ruptured retinal vessels on ophthalmoscopy, and petechiae on the neck and head. Common signs of oral trauma include a torn frenulum of the upper lip, broken teeth, torn lingual frenulum and contusions of the uvula, hard and soft palate.13

Next examine the neck, trunk (chest, breasts, ribs and abdomen), upper limbs (including cubital fossae, hands, fingers and fingernails) and lower limbs looking for signs of extragenital trauma. The most commonly injured extragenital areas are the mouth, throat, wrist, arms, breasts and thighs.14 Document the presence, size and location of bruises, lacerations, bite marks and scratches.

Examination of the genitalia should occur last, giving time for confidence to build in the patient. Take the time to cover the rest of the woman’s body while doing this examination, so as to provide her with as much dignity as possible. It is important to conduct the genital examination in a routine fashion, starting with the pubic area and noting the state of the vulva, perineum, introitus and posterior fourchette, the hymen, buttocks and anus, before doing a vaginal examination with a speculum (lubricated with warm water only) and examining the vaginal walls and cervix. Rape may not cause any obvious genital injury and it is important to remember that absence of genital injury does not imply consent or exclude penetration,15 and that many women who have consensual sex can have small grazes or fissures at the posterior fourchette.

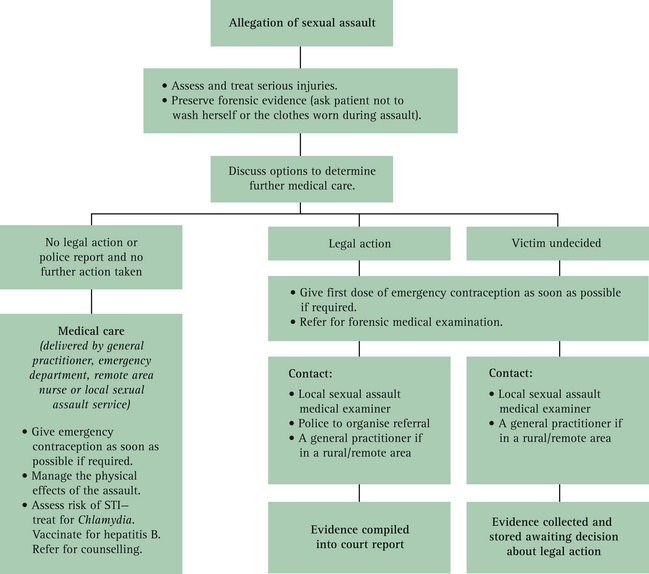

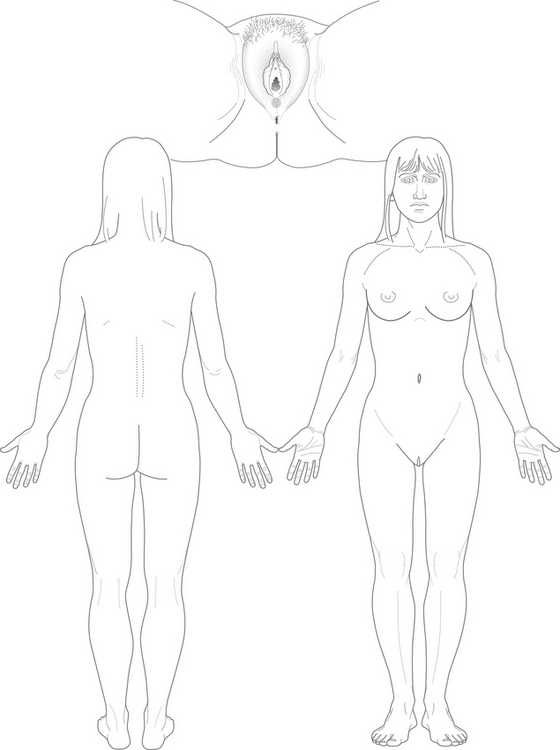

If the patient consents, photograph the area(s) of trauma, incorporating a size reference such as a ruler in the area being photographed. If consent is refused, diagrams can be used to record the location of any findings during the examination (Fig 17.2) and to describe the injuries as they are seen (e.g. grazes on both knees, scabbed and crusted).

It is important to warn the woman that contusions may not become visible for at least 48 hours.16 She may like to return to see you for further examination and documentation of those injuries at that time.

How common are injuries in cases of sexual assault?

Retrospective studies of women attending an emergency department for management after sexual assault have found that injuries are present in about half of people reporting sexual assault, with non-genital injuries more common than genital injuries.17–20 The absence of extragenital or genital trauma, however, does not mean that a sexual assault did not occur.

Box 17.3 lists some facts relating to sexual assault.

What specimens should be collected?

The swabs used for the collection of forensic specimens are plain cotton swabs, wetted with either a little tap water or normal saline. These are rubbed on a part of the body (e.g. nipple, upper arm), a smear is made on a clean glass slide and both the smear and swab are then air-dried. The swab should not be placed in transport media.

Swabs are generally taken from areas that have been directly affected by the rape. As part of evidence collection, the oral cavity should be swabbed. If oral penetration took place, swab the oropharynx for gonorrhoea testing21 and the mouth for semen. Sperm have been recovered from the oral cavity up to six hours after an assault, even if the teeth were brushed or mouthwash was used.22

Scrapings should be collected from underneath all ten fingernails, because they may reveal skin, blood, hair, trace fibres and secretions that may help identify the assailant.23 Pubic hair can be combed, and the hair and debris collected are placed in an envelope. Secretions pooled in the posterior fornix can be aspirated and placed in a sterile container.

What medical problems can arise from a sexual assault?

The exact risk of developing an STI after a sexual assault is difficult to quantify because:

The risk of transmission of STIs depends on the local prevalence of STIs (i.e. in the community to which the assailant(s) belong(s)), condom usage, the number of sexual contacts (assailants) and the nature of the sexual acts involved.24 Risk is higher when the assault has involved penetrative sex and ejaculation. Genital and non-genital injuries may facilitate the transmission of blood-borne viruses.

The most common infections found in victims are those that are most prevalent in the general community—Chlamydia, Trichomonas and gonorrhoea.24 There are reports of the transmission of HIV25 and HBV26 as a result of a sexual assault. The risk of HIV acquisition from one sexual encounter has been estimated at <1–2% (0.1–0.2% for receptive vaginal and 1–2% for penile–anal exposure).27 Epidemiological studies indicate that high-risk assaults are those that include anal rape, trauma (including that resulting from sexual violence), bleeding, defloration or multiple assailants, and that high-risk assailants are those known to have HIV or risk factors, such as injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, or those from a high prevalence area for HIV.28 Human papilloma virus may also be transmitted but becomes apparent only when visible genital warts emerge or on a Pap smear some months after the attack.

The other major risk to the woman is that of becoming pregnant as a result of the sexual assault. One study found an overall pregnancy rate of 5% per assault (the majority of pregnancies occurring in adolescent girls and young women usually in the context of family abuse or date rape).29 The real risk of pregnancy, however, is dependent on the timing of the assault in relation to where the woman is in her menstrual cycle and whether there is concurrent use of long-acting contraceptives. A young woman who is vaginally assaulted between 6 days prior to ovulation and 1 day after ovulation and who is not currently using a non-coitus-dependent method of contraception (such as oral contraceptives, Depo-Provera®, implants or an IUD) may experience a pregnancy risk approaching 30%.30

What diagnostic tests should be carried out in relation to these risks?

When a woman presents immediately after a sexual assault, diagnostic testing is carried out in two phases. Initially, tests should be performed to ascertain if the woman is already pregnant or suffering from an STI. Follow-up testing weeks to months later will tell whether or not she has become pregnant or picked up an STI as a result of the assault. The testing schedule is given in Table 17.1.

TABLE 17.1 Screening recommendations for sexually transmissible infections

| Infection | Test | Site (take specimen according to history) |

|---|---|---|

| HIV | HIV antibody | Blood |

| Hepatitis B | Hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg), core antibody (anti-HBc) and surface antibody (anti-HBs) | Blood |

| Syphilis | Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) + treponema pallidum haemagglutination assay (TPHA) | Blood |

| Chlamydia | Polymerase chain reaction | Endocervical swab, first-void urine or high vaginal swab |

| Gonorrhoea | Polymerase chain reaction or microscopy, culture and sensitivity (M, C and S) | Endocervical swab, first-void urine, rectal swab* or throat swab* |

| Trichomonas | Microscopy, culture and sensitivity (M, C and S) | High vaginal swab |

* M, C and S only, as PCR is not validated for these sites.

(From Mein et al10)

When should prophylaxis against STIs be offered?

GPs should offer prophylaxis for STIs if:

Pretest HIV counselling must be given. The theory behind treatment is to prevent infection by treating patients during a ‘window of opportunity’. If the assailant cannot be apprehended and tested, as in most cases, the victim’s infection status may not be known for several months. Not only may this delay foster anxiety and fear, but lifestyle changes may be necessary (e.g. need for condom use or abstaining from intercourse, postponing planned pregnancies, discontinuing breastfeeding). Therefore treatment must be made on a case-by-case basis, benefits must be weighed against lifestyle changes, and cost and potential drug toxicity must be considered. Table 17.2 (p 320) summarises the prophylactic medications that can be used.

TABLE 17.2 Suggested prophylaxis for sexually transmissible infections (treatment for high risk is shown in bold type)

| STI | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Chlamydia | Azithromycin (1 g orally) |

| Hepatitis B | |

| Gonorrhoea (only if high risk) | |

| Syphilis (if high risk) | Benzathine penicillin (1.8 g intramuscularly) |

| HIV (if high risk) | Phone local infectious diseases or sexual health physician urgently |

| Other STIs | Consult local infectious diseases or sexual health physician |

STI = sexually transmitted infection

* Available from Commonwealth Serum Laboratories

(From Mein et al10)

What psychological sequelae can occur as a result of sexual assault?

The mental health effects of rape are profound. As early as 1974, a landmark study described the ‘rape trauma syndrome’, identifying rape as a predisposing cause of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).31 More recently sexual violence has been recognised as a ‘trauma’ that can precipitate an acute stress disorder as well as PTSD.

Acute stress reaction

Post-traumatic stress disorder

If symptoms occur or continue beyond 1 month, the patient has post-traumatic stress disorder. PTSD is an anxiety disorder that is precipitated by a trauma. The essential feature of PTSD is that its development is anchored to a traumatic event of an extreme nature. Most survivors of trauma will develop an acute core constellation of PTSD symptoms: re-experiencing, avoidance and arousal. PTSD is diagnosed if these symptoms, together with social and occupational impairment, persist 4 weeks beyond the trauma itself. The DSM-IV-TR criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD are given in Box 17.4.

BOX 17.4 The DSM-IV-TR criteria for a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder

(From American Psychiatric Association32)

There must be a traumatic event that meets the following (criterion A):

There must also be symptoms from each of the following three categories:

Unfortunately the prevalence of PTSD is high after rape. The immediate consequence of rape is that 95% of the victims develop PTSD symptoms within 1 to 2 weeks of the crime. At 3 months post rape, nearly half continue to meet PTSD criteria.33

Are there any other health effects of sexual assault?

Women who have been sexually assaulted often present further down the track with a range of symptoms and conditions such as dyspareunia, pelvic pain, irritable bowel symptoms, weight management issues, premenstrual disorder symptoms, migraine headaches or fibromyalgia.34–37 Few women make the connection between the violence they have experienced in their lives and their current symptoms, with many feeling that the trauma has no bearing on the present complaint.38

Victims of sexual assault can also develop psychiatric conditions other than PTSD, such as depression, anxiety, somatisation, obsessive compulsive disorder, panic, paranoia, substance use disorders, eating disorders and borderline personality disorder.39–44 Sexual dysfunction is also a relatively common occurrence after a sexual assault.45

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree