Chapter 533 Vesicoureteral Reflux

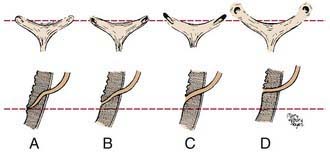

Vesicoureteral reflux refers to the retrograde flow of urine from the bladder to the ureter and kidney. The ureteral attachment to the bladder normally is oblique, between the bladder mucosa and detrusor muscle, creating a flap-valve mechanism that prevents reflux (Fig. 533-1). Reflux occurs when the submucosal tunnel between the mucosa and detrusor muscle is short or absent. Reflux usually is congenital, occurs in families, and affects approximately 1% of children.

Reflux predisposes to infection of the kidney (pyelonephritis) by facilitating the transport of bacteria from the bladder to the upper urinary tract (Chapter 532). The inflammatory reaction caused by a pyelonephritic infection can result in renal injury or scarring, also termed reflux-related renal injury or reflux nephropathy. In children with a febrile urinary tract infection (UTI), those with reflux are 3 times more likely to develop renal injury compared to those without reflux. Extensive renal scarring impairs renal function and can result in renin-mediated hypertension (Chapter 439), renal insufficiency or end-stage renal disease (Chapter 529), impaired somatic growth, and morbidity during pregnancy.

Classification

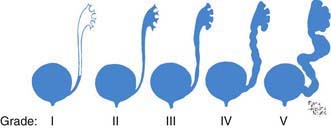

Reflux severity is graded using the International Reflux Study Classification of I to V and is based on the appearance of the urinary tract on a contrast voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) (Figs. 533-2 and 533-3). The higher the reflux grade, the greater the likelihood of renal injury. Reflux severity is an indirect indication of the degree of abnormality of the ureterovesical junction.

Reflux may be primary or secondary (Table 533-1). Bladder and bowel dysfunction instability can worsen pre-existing reflux if there is a marginally competent ureterovesical junction. In the most severe cases, there is such massive reflux into the upper tracts that the bladder becomes overdistended. This condition, the megacystis-megaureter syndrome, occurs primarily in boys and may be unilateral or bilateral (Fig. 533-4). Reimplantation of the ureters into the bladder to correct reflux resolves the condition.

Table 533-1 CLASSIFICATION OF VESICOURETERAL REFLUX

| TYPE | CAUSE |

|---|---|

| Primary | Congenital incompetence of the valvular mechanism of the vesicoureteral junction |

| Primary associated with other malformations of the ureterovesical junction | |

| Secondary to increased intravesical pressure | |

| Secondary to inflammatory processes | |

| Secondary to surgical procedures involving the ureterovesical junction | Surgery |

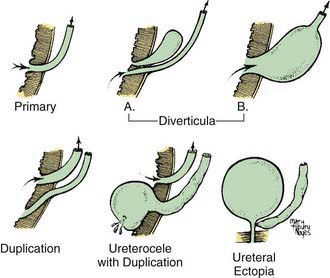

Approximately 1/125 children have a duplication of the upper urinary tract in which 2 ureters rather than 1 drain the kidney. Duplication may be partial or complete. In partial duplication, the ureters join above the bladder and there is 1 ureteral orifice. In complete duplication, the attachment of the lower pole ureter to the bladder is superior and lateral to the upper pole ureter. The valve-like mechanism for the lower pole ureter often is marginal, and reflux into the lower ureter occurs in as many as 50% of cases. Reflux occurs into both the lower and upper systems in some persons (Fig. 533-5). With a duplication anomaly, some patients have an ectopic ureter, in which the upper pole ureter drains outside the bladder (Chapters 534 and 537 and see Figs. 537-6 and 537-7). If the ectopic ureter drains into the bladder neck, typically it is obstructed and refluxes. Duplication anomalies also are common in children with a ureterocele, which is a cystic swelling of the intramural portion of the distal ureter. These patients often have reflux into the associated lower pole ureter or the contralateral ureter. Generally reflux is present when the ureter enters a bladder diverticulum (Fig. 533-6).

Figure 533-5 Various anatomic defects of the ureterovesical junction associated with vesicoureteral reflux.

Primary reflux occurs in association with several congenital urinary tract abnormalities. Of children with a multicystic dysplastic kidney or renal agenesis (Chapter 531), 15% have reflux into the contralateral kidney, and 10-15% of children with a ureteropelvic junction obstruction have reflux into either the hydronephrotic kidney or the contralateral kidney.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree