Chapter 161 Vasculitis Syndromes

Childhood vasculitis encompasses a broad spectrum of diseases that share a common denominator, inflammation of the blood vessels. The pathogenesis of the vasculitides is generally idiopathic; some forms of vasculitis are associated with infectious agents and medications, and others may occur in the setting of preexisting autoimmune disease. The pattern of vessel injury provides insight into the form of vasculitis and serves as a framework to delineate the different vasculitic syndromes. The distribution of vascular injury includes small vessels (capillaries, arterioles, and postcapillary venules), medium vessels (renal arteries, mesenteric vasculature, and coronary arteries), and large vessels (the aorta and its proximal branches). Additionally, some forms of small vessel vasculitis are characterized by the presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), whereas others are associated with immune complex deposition in affected tissues. A combination of clinical features, histologic appearance of involved vessels, and laboratory data is utilized to classify vasculitis (Tables 161-1 to 161-3).

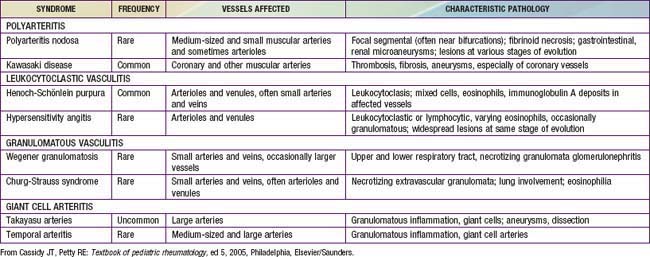

Table 161-1 CLASSIFICATION OF CHILDHOOD VASCULITIS

I. PREDOMINANTLY LARGE VESSEL VASCULITIS

II. PREDOMINANTLY MEDIUM VESSEL VASCULITIS

III. PREDOMINANTLY SMALL VESSEL VASCULITIS

IV. OTHER VASCULITIDES

* Associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

Adapted from Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al: EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides, Ann Rheum Dis 65:936–941, 2006.

Table 161-2 FEATURES THAT SUGGEST A VASCULITIC SYNDROME

CLINICAL FEATURES

LABORATORY FEATURES

From Cassidy JT, Petty RE: Textbook of pediatric rheumatology, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2005, Elsevier/Saunders.

Bibliography

Dedeoglu F, Sundel RP: Vasculitis in children, Rheum Dis Clin North Am 33:555–583, 2007.

161.1 Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Pathology

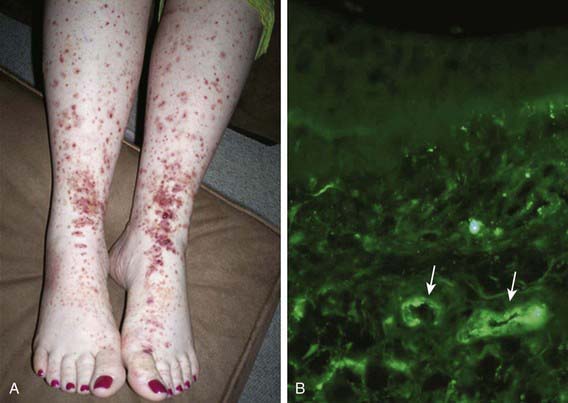

Skin biopsies demonstrate vasculitis of the dermal capillaries and postcapillary venules. The inflammatory infiltrate includes neutrophils and monocytes. Renal histopathology typically shows endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis, ranging from a focal segmental process to extensive crescentic involvement. In all tissues, immunofluorescence identifies IgA deposition in walls of small vessels (see Fig. 161-1), accompanied to a lesser extent by deposition of C3, fibrin, and IgM.

Clinical Manifestations

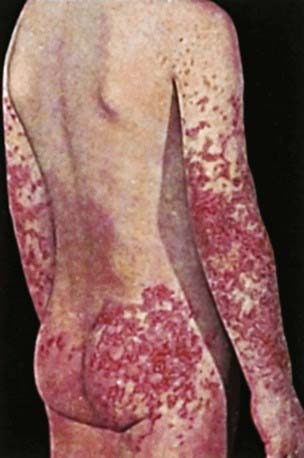

The hallmark of HSP is its rash: palpable purpura starting as pink macules or wheals and developing into petechiae, raised purpura, or larger ecchymoses. Occasionally, bullae and ulcerations develop. The skin lesions are usually symmetric and occur in gravity-dependent areas (lower extremities) or on pressure points (buttocks) (Figs. 161-1 and 161-2). The skin lesions often evolve in groups, typically lasting 3-10 days, and may recur up to 4 mo after initial presentation. Subcutaneous edema localized to the dorsa of hands and feet, periorbital area, lips, scrotum, or scalp is also common.

Figure 161-2 Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

(From Korting GW: Hautkrankheiten bei Kindern und Jungendlichen, ed 3, Stuttgart, 1982, FK Schattaur Verlag.)

Renal involvement occurs in up to 50% of children with HSP, manifesting as hematuria, proteinuria, hypertension, frank nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and acute or chronic renal failure. Progression to end-stage renal disease is uncommon in children (1-2%) (see Chapter 509 for more detailed discussion of HSP renal disease).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of HSP is a clinical one and is often straightforward when the typical rash is present. However, in at least 25% of cases, the rash appears after other manifestations, making early diagnosis challenging. Classification criteria for HSP are summarized in Table 161-4. The differential diagnosis for HSP depends on specific organ involvement but usually includes other small vessel vasculitides, infections, coagulopathies, and other acute intra-abdominal processes.

Table 161-4 CLASSIFICATION CRITERIA FOR HENOCH-SCHÖNLEIN PURPURA*

AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY CLASSIFICATION CRITERIA†

EUROPEAN LEAGUE AGAINST RHEUMATISM/PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY EUROPEAN SOCIETY CRITERIA‡

* Classification criteria are developed for use in research and not validated for clinical diagnosis.

† Developed for use in adult and pediatric populations. Adapted from Mills JA, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al: The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for classification of Henoch-Schonlein purpura, Arthritis Rheum 33:1114–1121, 1990.

‡ Developed for use in pediatric populations only.

Adapted from Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ et al: EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides, Ann Rheum Dis 65:936–941, 2006.

Acute hemorrhagic edema (AHE), an isolated cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis that affects infants <2 yr of age, resembles HSP clinically. AHE manifests as fever; tender edema of the face, scrotum, hands, and feet; and ecchymosis (usually larger than the purpura of HSP) on the face and extremities (Fig. 161-3). The trunk is spared, but petechiae may be seen in mucous membranes. The patient usually appears well except for the rash. The platelet count is normal or elevated, and the urinalysis results are normal. The younger age, the nature of the lesions, absence of other organ involvement, and a biopsy may help distinguish AHE from HSP.

Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long term prognosis of Henoch-Schonlein nephritis in adult and children. Italian Group of Renal Collaborative Study on Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

Davin JC, Weening JJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis: an update. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:689-695.

Donnithorne KJ, Atkinson P, Hinze CH, et al. Rituximab therapy for severe refractory chronic Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J Pediatr. 2009;155:136-139.

Hoffman GS. Therapeutic interventions for systemic vasculitis. JAMA. 2010;304(21):2413-2414.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree