CHAPTER 8 Vaginal Infections and Sexually Transmitted Diseases

VULVOVAGINITIS AND COMMON VAGINAL INFECTIONS

The normal vaginal environment is a dynamic milieu with a constantly changing balance of Lactobacillus acidophilus and other endogenous flora, glycogen, estrogen, pH, and metabolic byproducts of flora and pathogens.1 L. acidophilus produces hydrogen peroxide that limits the growth of pathogenic bacteria.2 Disturbances in the vaginal environment can allow the proliferation of vaginitis-causing organisms. The term vulvovaginitis actually encompasses a variety of inflammatory lower genital tract disorders that may be secondary to infection, irritation, allergy, or systemic disease.3 Vulvovaginitis is the most common reason for gynecologic visits, with over 10 million office visits for vaginal discharge annually.4 It is usually characterized by vaginal discharge, vulvar itching and irritation, and sometimes vaginal odor.5 Up to 90% of vaginitis is secondary to bacterial vaginosis (BV), vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), and trichomoniasis. The actual prevalence and causes of vaginitis, however, are hard to gauge because of the frequency of self-diagnosis and self-treatment.1 In one survey of 105 women with chronic vaginal symptoms, 73% had self-treated with OTC products and 42% had used alternative therapies. On self-assessment, most women thought they had recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC), but upon diagnosis, only 28% were found positive for RVVC. Women with a prior diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), however, were able to accurately self-diagnose up to 82% of the time based solely on symptoms.6 This may, however, be an overestimate, as in another study (questionnaire) of 634 women, only 11% were able to accurately recognize the classic symptoms of VVC.6 Another study of women who thought they had VVC also found that self-assessment had limited accuracy, with only 33.7% of women with self-diagnosed yeast infection having microscopically confirmable cases.7

Two-thirds of patients with vaginal discharge have an infectious cause.2 However, the presence of some amount of vaginal secretions can be normal, varying with age, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and the use of OCs.

Antibiotics, contraceptives, vaginal intercourse, receptive oral sex, stress, and hormones (e.g., HRT, endogenous hormonal dysregulation) can lead to overgrowth of pathogenic organisms.1 Chemical vulvovaginitis can be caused by colored and perfumed soaps, toilet paper, bubble baths, panty liners, tampons, sanitary pads, and douches. Latex condoms, topical antifungal agents, and preservatives and other agents in lubricants can cause allergic reactions leading to vulvovaginitis.2 In menopausal women, or those on antiestrogen therapies, decreased estrogen levels may lead to atrophic vaginitis, which if asymptomatic generally requires no treatment. Forty percent of postmenopausal women, however, are symptomatic; symptoms are readily treatable with topically applied lubricants, and the use of estrogen replacement therapies by topical or oral administration.

Although vaginal complaints may commonly be treated based on symptoms, studies have demonstrated a poor correlation between symptoms and diagnosis.8,9 Therefore, the most accurate diagnoses and thus the most appropriate treatments, can best be made with testing methods specific for individual organisms. Acute singular episodes of vaginal infections are referred to as uncomplicated, whereas recurrent vaginal infections are considered complicated. Complicated cases are often more severe, resistant to treatment, and may be associated with underlying systemic causes, for example, in VVC, uncontrolled diabetes, or immunosuppression.2

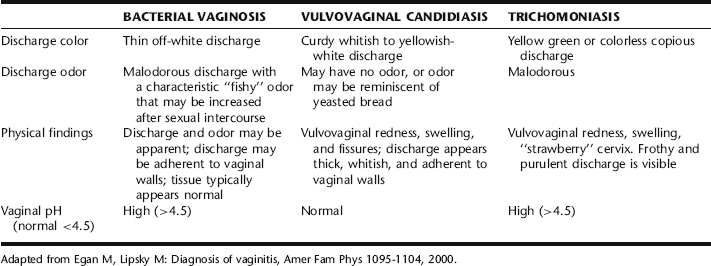

The remainder of this section presents seperate discussions of the most common vaginal infections (Table 8-1) followed by a discussion of the botanical treatment of vaginal infections. Table 8-2 provides a general overview of common causative organisms, agents, and conditions involved in vulvovaginitis. It should be remembered that multiple causes of vaginitis may occur concurrently.2

TABLE 8-2 Common Causative Organisms, Agents, and Conditions Involved in the Etiology of Vulvovaginitis

| ORGANISM/AGENT/CONDITION | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Bacterial vaginosis (BV) | Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, other anaerobic microorganisms |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) | Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida glabrata, other Candida species |

| Trichomoniasis | Trichomoniasis vaginalis |

| Chemical vulvovaginitis | Feminine hygiene products: tampons, sanitary pads, douches, latex condoms, spermicides, colored and perfumed soaps, toilet paper, bubble baths |

| Allergic vulvovaginitis | Latex condoms, topical antifungal agents, and preservatives and other agents in lubricants |

| Atrophic vulvovaginitis | Estrogen deficiency due to menopause, anti-estrogenic therapies, or hormonal dysregulation |

| General causes/factors that might lead to or increase susceptibility to vulvovaginal infection and VVC | Antibiotics, oral contraceptives, use of diaphragms, spermicide, IUDs, frequent vaginal intercourse, receptive oral sex, stress, public hot tubs, hormones (e.g., imbalanced endogenous hormones, HRT), uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression (HIV/AIDS, steroids), pregnancy |

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common form of infectious vaginitis caused by the polymicrobial proliferation of Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, and other anaerobes. It is associated with loss of normal lactobacilli.2 BV accounts for at least 10% and as many as 50% of all cases of infectious vaginitis in women of childbearing age.1,7 Determining the presence of BV can be difficult, however, because as many as 75% of women are asymptomatic.1

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the Amstel criteria, which is considered 90% accurate with three or four of the following findings: the presence of milky, homogenous discharge, vaginal pH greater than 4.5 positive whiff test (“fishy” odor to the vaginal discharge), and the presence of clue cells on light microscopy of vaginal fluid. Odor is a symptom that is frequently associated with BV, due to amines produced from the breakdown products of amino acids produced by Gardnerella vaginalis in the presence of anaerobic bacteria. This also results in a rise in vaginal pH.2

Risks for Developing BV

Numerous factors, described in Table 8-3, are associated with the development of BV. It is uncertain whether BV is a sexually transmitted disease. The prevalence is higher in women with multiple sexual partners and in women seeking the services of STD clinics. Treatment of sexual partners of women with the infection has not definitely proved to be beneficial; however, urethral smears of male partners often show typical BV morphocytes.1,2,5

TABLE 8-3 Factors Associated with the Development and Pathophysiology of Bacterial Vaginosis

| TYPE OF RISK FACTOR | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Personal risk factors | Sexual practices: new or multiple sexual partners, receptive oral sex, latex condoms, contraceptive methods such as cervical cap, IUD, or spermicide |

| Microbial factors |

Risks Associated with BV

BV in pregnancy appears to be a risk factor for second trimester miscarriage, premature rupture of the membrane and premature labor, chorioamnionitis, and post-cesarean and postpartum endometritis.10,11 Women with BV have an increased incidence of abnormal Pap smears, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and endometritis. Further, the presence of BV in women undergoing invasive gynecologic procedures may increase the risk of serious infection including vaginal cuff cellulitis, PID, and endometrirtis.1 Eliminating BV appears to decrease the risk of acquiring HIV infection; thus, it is suggested that women with BV be treated regardless of whether they are symptomatic.5

Conventional Treatment of BV

CDC guidelines recommend the treatment of all women with symptomatic BV.5 Conventional treatment of BV is metronidazole (Flagyl) orally or vaginally (Metro-gel), or Clindamycin. Proper treatment typically results in an 80% cure rate at 4 weeks, with recurrence rates of 15% to 50% in 3 months.2 Treatment failure may be caused by lack of successful recolonization of hydrogen peroxide producing strains of lactobacillus, antibiotic resistance, and possibly reinfection by male partners.

Metronidazole is also the prescribed treatment during pregnancy; however, it is contraindicated in the first trimester because of theoretic risks of teratogenicity. Thus, many pregnant women prefer to avoid exposure altogether.10,11 Clindamycin is used as an alternative.1 Evidence on the use of antibiotics in pregnancy to reduce the risk of preterm labor and its associated morbidities is somewhat conflicting. A Cochrane review concluded that no evidence supports the screening of all women for BV, and Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) also does not recommend screening in asymptomatic patients.12,13 According to a recent (2005) systematic review, no evidence supports the use of antibiotic treatment for either BV or Trichomonas vaginalis (see later in this section) for reducing preterm birth in low- or high-risk women.14 Nonetheless, CDC Guidelines (2002) still recommend treatment of all pregnant women with Metronidazole or Clindamycin.5

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), commonly referred to as yeast infection, is the second most common cause of vaginitis in the United States. Approximately 75% of all women will experience an episode of VVC in their lifetime, with RVVC occurring in 5% of women.1,3 It is most commonly caused by the fungus Candida albicans; however, other Candida species, such as C. tropicalis and C. glabrata are becoming increasingly common, possibly because of increased use of OTC antifungals, and they are also typically more resistant to antifungal treatments.1 OTC antifungal treatments are among the top 10 selling OTC medications in the United States with an estimated $250 in annual sales.6 Establishing Candida as a cause of vaginitis can be difficult, because 50% of all women have Candida organisms as part of their normal vaginal flora.1 Candida is not considered a sexually transmitted disease, and conventional medical practice does not include treatment of male partners unless uncircumcised or presenting with inflammation of the glans penis.1 RVVC is defined as four or more episodes annually.2 Recurrence may be a result of associated factors, intestinal microorganism reservoir, vaginal persistence, or sexual transmission.1 Genital candidiasis is associated with antibiotic use, oral contraceptives and HRT, and other drugs that change the vaginal environment to favor proliferation of Candida. Vaginal yeast infections are also more common during pregnancy and menstruation, and in diabetics. Drugs and diseases that suppress the immune system can facilitate infection.

Causes and Risk Factors for Developing VVC

Reported risk factors include:

Additional factors may include anything that disrupts the normal balance of vaginal flora, which are listed in Table 8-2.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of Candida can be based on positive microscopic findings.6 Cultures are expensive, but obtaining a positive fungal culture can be important for the diagnosis and effective treatment of RVVC.6 Candida vaginitis is associated with a normal vaginal pH (≤ 4.5). Identifying Candida by culture in the absence of symptoms is not an indication for treatment, because it is a part of the normal endogenous flora.

Conventional Treatment Approaches of VVC

Uncomplicated VVC is intermittent and infrequent, and in 80% to 90% of cases results in resolution of symptoms and negative culture after a short course of topical azole drugs.5 Examples of azole-containing antifungal creams include: clotrimazole, miconazole, ketoconazole, and fluconazole. These are currently available OTC. The duration of treatment with these preparations may be 1, 3, or 7 days. Alternatively, ketoconazole, fluconazole (Diflucan), itraconazole, or Nystatin can be taken orally. Self-medication with OTC preparations should be advised only for women who have been diagnosed previously with vaginal Candida infection and who have a recurrence of the same symptoms. Any woman whose symptoms persist after using an OTC preparation or who has a recurrence of symptoms within 2 months should seek medical care. Treatment with azoles results in relief of symptoms and negative cultures among 80% to 90% of patients who complete therapy. Topical agents usually are free of systemic side effects, although local burning or irritation may occur. A maximum of 7 days of topical therapy is recommended during pregnancy. Oral agents lead to better compliance but have a greater risk for systemic toxicity, and occasionally may cause nausea, abdominal pain, dizziness, rash, or headaches.15 Therapy with the oral azoles occasionally has been associated with abnormal elevations of liver enzymes. Occasionally, women who take oral contraceptives must stop using them for several months during treatment for vaginal candidiasis because they can worsen the infection. Women who are at unavoidable risk of vaginal candidiasis, such as those who have an impaired immune system or who are taking antibiotics for a long period of time, may need an antifungal drug or other preventive therapy. For women with complicated VVC (RVVC), a longer duration of therapy may be recommended, followed by a 6-month period of maintenance therapy.5 Azole drugs may significantly interact with a number of drugs (e.g., astemizole, cisapride, H1-antihistamines interactions have been associated with cardiac dysrhythmia) owing to potent inhibition of cytochrome P3A4, leading to increased bioavailability of the interacting drug.2

TRICHOMONIASIS

Trichomoniasis vaginalis is a motile, flagellate protozoan. It is the third most common cause of vaginitis. Every year, approximately 180 million women worldwide are diagnosed with this infection annually, accounting for 10% to 25% of all vaginal infections.1 Current belief is that T. vaginalis is almost exclusively acquired through sexual contact.2 Male sexual partners are infected in 30% to 80% of cases.1

Symptoms

Symptomatic infection causes a characteristic frothy green malodorous discharge with a high pH (can be as high as 6.0).5 Additionally, there may be soreness and irritation in and around the vulva and vagina, dysuria, dyspareunia, bleeding upon intercourse, inability to tolerate speculum insertion because of pain, or a superficial rash on the upper thighs with a scalded appearance. The cervix may have a characteristic appearance, called petechial strawberry cervix, in up to 25% of cases.1 Chronic asymptomatic infection can exist for decades in women; an infection also may present atypically.2 In men, infection is mostly asymptomatic, or there may be a thin white or yellow purulent discharge with dysuria (nongonococcal urethritis).2,5

Diagnosis

Trichomoniasis can be diagnosed on the basis of simple microscopy, pH evaluation, and amine tests.2 However, in as many as 50% of cases, microscopy yields negative findings in spite of strong evidence of T. vaginalis infection. In this case, PCR can be used to obtain a definitive diagnosis; however, it is more costly.

Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Trichomoniasis

Smoking, IUD use, and multiple sexual partners all increase the risk of contracting T. vaginalis.1 Statistically, black unmarried women who smoke cigarettes, use illicit drugs, less educated teenagers, and those of low socioeconomic groups are more likely to be colonized with this organism, as are women who have had greater than five sexual partners in the past 5 years, have a history of gonorrhea or other STDs, and who have an early age at first intercourse.

Risks Associated with Trichomoniasis Infection

Trichomoniasis is associated with and may act as a vehicle of transmission for other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.1,2,7 It is also associated with an increased risk of premature rupture of the membrane, premature birth, and low birth weight.2,5

Conventional Treatment of Trichomoniasis Infection

CDC treatment guidelines for treatment of T. vaginalis infection is oral metronidazole, which has a cure rate of 90% to 95%. Unlike with other vaginal infections, treatment is recommended regardless of whether a woman is symptomatic.7 Treatment success may be increased with treatment of sexual partners. Sex is to be avoided until the patient and any sexual partners are cured. Follow-up is considered unnecessary in patients who are initially asymptomatic or who become asymptomatic after treatment is completed. Oral metronidazole is recommended for treatment of symptoms in pregnant women.5 Treatment during pregnancy has not been shown to reduce the risk of preterm delivery.7 Also, as stated, physicians and pregnant women may be hesitant to use this drug during pregnancy owing to potential risks of teratogenicity. A recent Cochrane review found no benefit from antimicrobial treatment for T. vaginalis during pregnancy, and in fact, implies possible harm from treatment on the basis that the largest trial was stopped early due to increased risk of preterm labor with metronidazole treatment.14 As this is the only medication used to treat T. vaginalis, hypersensitivity and drug resistance are potential obstacles to therapy. Increasing dosage may overcome resistance, and a desensitization protocol is used in cases of hypersensitivity to the drug.7 Additionally, other drugs are available in Europe but have not yet been approved by the FDA for use in the United States.7

THE BOTANICAL PRACTITIONER’S PERSPECTIVE

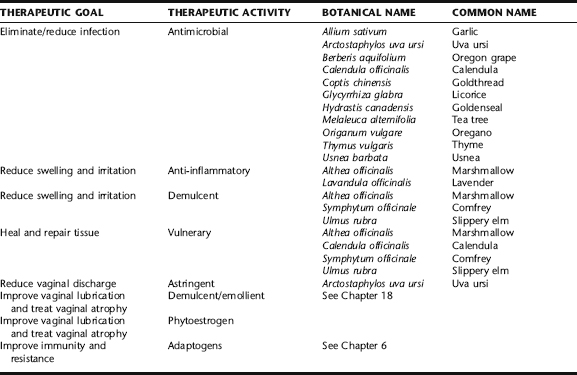

Research and clinical experience indicate that women commonly seek OTC and alternative therapies for the treatment of vaginal infections and vulvovaginitis (Table 8-4). In one study, 105 patients, with a mean age of 36 years, and 50% with college degrees, referred by their gynecologists for evaluation of chronic vaginal symptoms, were interviewed about their OTC and alternative medicine use in the preceding year, it was found that 73% of patients had self-treated with OTC antifungal medications or povidone-iodine douching and 42% had tried alternative therapies including acidophilus pills orally (50%) or vaginally (11.4%), yogurt orally (20.5%) or vaginally (18.2%), vinegar douches (13.6%), and boric acid (13.6%).16

Vulvovaginitis may simply be an acute response to a temporary period of imbalance or recent exposure to precipitating factors, such as a period of stress at school or work, excessive consumption of sugar or alcohol at holiday time, or increased sexual activity with condom and spermicide use, affecting proper balance in local flora. In such cases, simple lifestyle modifications combined with topical applications are often adequate treatments. Recurrent vulvovaginitis may be part of a larger picture of chronic lifestyle imbalance, underlying conditions that disrupt the vaginal flora (e.g., bowel dysbiosis or hormonal dysregulation) or exposure to any of the many instigating causes mentioned earlier in this chapter (see Table 8-2). Complicated, recurrent vulvovaginitis can be more difficult to treat but can often be effectively addressed with a combination of local and systemic strategies and removal of underlying causes. Patients with intractable vulvovaginitis should be evaluated for serious underlying conditions such as immunosuppression or diabetes mellitus, and any botanical treatment should occur in conjunction with appropriate medical care. Although there is evidence in the medical literature to suggest that, with the exception of trichomoniasis, it is not necessary to treat sexual partners; empirical evidence from botanical clinical practice suggests that recurrence is less likely when all partners are treated. This should not be surprising, as with most vaginal infections, it has been found that men do harbor organisms in the urethra.

The goal of the botanical practitioner is to reduce or eliminate factors that encourage infection or overgrowth of pathogenic organisms, restore the normal vaginal environment and its flora, and relieve symptoms associated with infection. This chapter does not address hormonal dysregulation that may be associated with vulvovaginitis.

Antimicrobial Therapy

Antimicrobial herbs are used as primary treatments in cases of vulvovaginitis when due to infectious causes. For acute infections, they are generally used solely as topical applications. For recurrent cases, external application is combined with oral use. Internal treatment should focus on immune supporting and antimicrobial botanicals, including echinacea, garlic, goldenseal, Oregon grape root, Pau d’arco, astragalus, and various medicinal mushroom species such as maitake and reishi medicinal mushrooms. Also see Chapter 7 for a discussion on adaptogens and immune support.

Garlic

Garlic is a popular antimicrobial botanical treatment for vaginal infections, effective when applied in fresh whole form. A single clove is carefully peeled and inserted whole at each application, usually at night, and left in during sleep. It is sometimes dipped in a small amount of vegetable oil to ease insertion. It also may be wrapped in a small piece of gauze or with a piece of string with a tail left hanging to ease removal. Otherwise, it can be removed manually. In vitro, garlic has demonstrated antimicrobial effects against a wide range of bacteria and fungi, including E. coli, Proteus, Mycobacterium, and Candida species.17 In a study by Sandhu et al., 61 yeast strains, including 26 strains of C. albicans were isolated from the vaginal, cervix, and oral cavity of patients with vaginitis and were tested against aqueous garlic extracts. Garlic was fungistatic or fungicidal against all but two strains of C. albicans. In another in vitro study, an aqueous garlic extract effective against 22 strains of C. albicans isolated from women with active vaginitis. At body temperature, garlic had mostly fungicidal activity; below body temperature, the action was mostly fungistatic.18,19 Cases of irritation and even chemical burn have been reported after prolonged application of garlic to the skin or mucosa.20

Goldenseal, Goldthread, and Oregon Grape Root

Goldenseal, goldthread, and Oregon grape are all herbs that contain the alkaloid berberine, a major active component possessing antimicrobial activity.21 In vitro studies demonstrate a rational use of the herb for its antibacterial properties.22,23 Berberine has demonstrated specific activity against C. albicans and C. tropicalis as well as to a species of trichomoniasis, T. mentagrophytes, among other pathogens.20,22 These herbs have been used historically and in modern herbal medicine with good reliability for the treatment of a variety of infectious conditions, both internally and topically. Goldenseal is considered by many herbalists to be the most effective of the three herbs. It is commonly included, as is Oregon grape root, as an ingredient in topical preparations for the treatment of vaginitis, added in powder or tincture form to suppositories or powder inserted vaginally in “00” capsules. Internal use of goldenseal, in addition to specific antimicrobial activity, may enhance immune response via stimulation of increased antibody production and may be suggested for oral use in intractable cases.24 Goldthread has demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity against a wide range of Candida species.25

Oral consumption of these herbs is generally contraindicated for use in pregnancy. Goldenseal root is an endangered North American plant. Therefore, only cultivated root should be purchased for use. Oregon grape and goldthread can be substituted with confidence.25

Licorice

Licorice root is one of the most widely used herbs for the treatment of a range of inflammatory conditions. It has demonstrated effectiveness as a demulcent in the treatment of oral, gastric, and respiratory tract conditions, including ulcers and inflammation.20 Although no research was identified on the use of this herb for vulvovaginitis, its effects on other mucosa would seem to substantiate this application. Additionally, licorice alcohol extracts have shown effectiveness against E. coli, and Candida and Trichomoniasis species in vitro. Alcohol extracts can easily be added to suppository blends for topical application.

Oregano and Thyme

The antimicrobial properties of essential oils have been known since antiquity. In vitro testing of essential oils against a wide variety of microorganisms, showed thyme and oregano to possess the strongest antimicrobial properties among many herbs that were tested.26 Thyme essential oil has also found to be specifically effective against Candida spp.27,28 Direct application of undiluted oil (neat oil) is not recommended as it is too caustic to the skin and sensitive mucosa. Rather, a small amount of essential oil can be added to suppository blends, diluted tincture may be added to peri-washes and sitz baths, and tea of these herbs may be used as a base to which other herbs may be added for peri-washes and sitz baths. See sample formulae in this chapter and Chapter 3.

Tea Tree

Tea tree oil (TTO) is derived from the leaves of the tea tree (Fig. 8-1), a native to Australia with a history of use of the leaves for the treatment of colds, coughs, and wounds by indigenous Australians, who spoke of healing lakes in which leaves of the tree had decayed. The medical use of the oil as an antiseptic was first documented in the 1920s, and led to its commercial production, which remained high throughout World War II.29 Legend has it that it was provided to Australian soldiers fighting in World War II for use as an antiseptic and that harvesters were exempt from enlisting.29 Reports of the effectiveness of TTO appeared in the literature from the 1940s through the 1980s, with a significant increasing interest in the medical value of TTO seen in the 1990s to the present, corresponding with interest in CAM generally. Current research, presented in a thorough review by Carson et al., supports its use as an antibacterial and antifungal, as well as an anti-inflammatory.29 Limited studies have been done on TTO’s use as an antiviral, but a few trials have indicated possible activity against enveloped and non-enveloped viruses.29 A broad range of bacteria have demonstrated in vitro susceptibility to TTO, including those known to be associated with BV. A case report in which a woman successfully self-treated with TTO-containing suppositories also supports the use of TTO in BV. 30 31 32 33 34 35 At concentrations lower than 1%, TTO may be bacteriostatic rather than antibacterial.29 Several studies have demonstrated efficacy against C. albicans; however, to date no clinical trials have been done. A rat model of vaginal candidiasis supports the use of TTO for VVC.30 The organisms on which numerous TTO antifungal studies have focused.32, 35 36 37 Two studies demonstrated antiprotozoal activity of TTO, one specifically supporting anecdotal evidence that TTO is effective against T. vaginalis. The mechanisms of antimicrobial action are similar for bacteria and fungi and appear to involve cell membrane disruption with increased permeability to sodium-chloride and loss of intracellular material, inhibition of glucose-dependent respiration, mitochondrial membrane disruption, and inability to maintain homeostasis.33, 38 39 40 Perhaps what has attracted the most interest about this herb is that it has demonstrated activity against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. It has been used in Australia since the 1920s has not led to the development of resistant strains of microorganisms, nor have studies that have attempted to induce resistance with the exception of one case of induced in vitro resistance in Staphylococcus aureus.41,42

Usnea

Usnea lichens (Fig. 8-2) have a history of use that spans centuries and countries from ancient China to modern Turkey, from rural dwellers in South Africa to modern day naturopathic physicians and herbalists in the United States.43,44 The lichen is rich in usnic acid, which has demonstrated in vitro antimicrobial activity against bacteria, viruses, protozoa. Additionally, it exhibits anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity.25 Alcohol extract may be added to a suppository blend or diluted in water or tea (1 tbs tincture/cup of liquid) for use as a peri-wash or in sitz baths.

Uva Ursi

Uva ursi is used by midwives as a topical antiseptic and astringent to relieve vulvar and urethral irritation associated with vulvovaginitis. Leaf preparations have shown antimicrobial activity against C. albicans, S. aureus, E. coli, and other pathogens.20 For vulvovaginitis, it is used topically as a peri-rinse or in sitz baths.

Symptomatic Relief and Tissue Repair

Calendula

Calendula has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of wounds, promoting tissue regeneration and re-epithelialization, and has also shown some antimicrobial activity (see the preceding). It is soothing as a tea, oil, or diluted tincture (1 tbs tincture to ¼ cup of water), and is an important ingredient in topical vulvovaginitis preparations.45 ESCOP recommends calendula for the treatment of skin and mucosal inflammation and to aid wound healing.46

Comfrey Root

Comfrey root (Fig. 8-3) has a very long history of folk use for healing damaged skin, tissue, and broken bones. It is highly mucilaginous. It is thought that allantoin and rosmarinic acid are the constituents mainly responsible for comfrey’s healing and anti-inflammatory actions.47 Comfrey is indicated for topical use only. Use on broken skin or mucosa should be minimized but is reasonable for short durations (1 to 2 weeks at a time), and should not exceed 100 µg of pyrrolizidine alkaloids with 1,2 unsaturated necine structure daily for a maximum of to 4 to 6 weeks annually.48 Comfrey infusion may be added to a peri-rinse or sitz-bath blend, or comfrey oil or finely powdered herb may be added to a suppository blend.

Lavender

Lavender has a folk tradition of use for topical treatment of mild wounds, for which it is still included by herbalists and midwives in topical preparations for vulvovaginitis.47 Additionally, its fragrance imparts a pleasant scent to herbal preparations. It may be used as a rinse or sitz bath in tea form or using diluted tincture, or several drops of essential oil may be added to rinses, sitz baths, or suppositories.

Marshmallow Root

Marshmallow is demulcent and vulnerary. Marshmallow root contains a mucilage that covers the mucosa, protecting it from local irritation.46 Topical application is soothing in sitz baths and peri-rinses, and the powdered herb, finely ground, helps give herbal suppositories firmness. Slippery elm bark powder can be substituted for marshmallow root powder in suppository blends.

Topical Preparations for Treating Vulvovaginitis

Sitz Baths, Peri-Washes, and Suppositories

The most common forms of topical applications used in the treatment of vulvovaginitis are sitz baths, peri-washes, and suppositories. Instructions for each of these preparations are found in Chapter 3.

Suppositories are applied nightly for 7 to 14 days. It is advisable to wear a light pad and old underwear while sleeping because the suppository will melt at body temperature. The oils and herbs may stain bedding or clothes.

Why Douching Is Not Recommended

Women commonly douche because of the misperception that it “cleans out” the vaginal canal and can thus cure vaginal infections. A systematic review found that although douching may provide some symptomatic relief and initial reduction in infection, it may lead to rebound effects and other complications in the long run. Povidone iodine preparations, a common OTC choice for self-treatment, have been demonstrated to cause a “rebound effect” in which a higher than normal bacterial colonization is seen within weeks of last douching, which could actually increase the risk of bacterial vaginosis. Routine douching for hygiene has been shown to double the risk of acquiring vaginitis. Douching of all types can lead to increased risks of PID, endometritis, salpingitis, and ectopic pregnancy.19

CHRONIC VULVOVAGINITIS AND INTESTINAL PERMEABILITY

Nutritional Considerations: Lactobacillus/Yogurt

The goal of treatment with lactobacillus supplements or yogurt, taken orally or applied vaginally, is recolonization of the vagina (and bowel with oral intake) with adequate numbers of healthy flora capable of controlling and resisting pathogenic infection. The success of this treatment requires products that contain the proper lactobacillus species and that these species be active. Additionally, oral yogurt therapy requires the survival of lactobacilli through the GI system and digestive processes, as it is thought that vaginal recolonization occurs as a result of migration of the microorganisms from the anus to the vaginal introitus.19 Effective oral and topical yogurt therapy also requires that the lactobacilli be able to adhere to the vaginal epithelium. L. acidophilus is poorly adherent to the vaginal walls, and it also is not a major rectovaginal species. Although two clinical trials have demonstrated significant efficacy with oral and/or topical use, the use of other species of lactobacillus, such as L. crispatus, L. jensenii, L. rhamnosus, and L. fermentum, may be more effective.20,49 A randomized crossover study with a washout period by Shalev et al. studied the effects of oral yogurt prophylaxis on a group of women (n = 46) with BV (n = 20) and candidal vaginitis (n = 18) or both (n = 8). The study showed a significant decrease in BV and no significant decrease in candidal infection. Only 28 participants were still enrolled in the study at 4 months and only 7 completed the protocol.51 In an open crossover trial by Hilton et al., a randomized group of women (n = 33) with RVVC were assigned to either a 6-month protocol of daily oral intake of L. acidophilus containing yogurt or a yogurt-free diet. A threefold decrease was seen in candidal infections, substantiated by wet mount and potassium hydroxide. Interestingly, although only 13 women completed the yogurt treatment, 8 women in the yogurt arm refused to switch over to the yogurt-free diet.51 Patients with lactose intolerance may experience GI complaints from oral yogurt intake. Topical treatment of BV with yogurt has been evaluated in several studies. In an unblinded study of 84 pregnant women with BV a program of yogurt douching twice daily for 7 days (n = 32) compared with acetic acid tampons (n = 20) or no treatment (n = 20), it was found after 2 months of treatment 88% of women in the yogurt group and 38% of women in the acetic acid group compared with 5% of women in the no treatment group were BV free. A multicenter, placebo-controlled RCT looking at the effects of lactobacillus vaginal tablets combined with estrogen as a delivery agent on BV demonstrated a 75% cure rate at 2 weeks and an 88% cure rate at 4 weeks compared with a 25% and 22% respective cure rates at corresponding times in the placebo group.19

Empiric evidence from herbal and midwifery practice suggests that live active culture yogurt may be more effective than acidophilus tablets or capsules, although any of the options is potentially effective. It is also provides some immediate relief of burning and itching to inflamed tissue. The easiest way to apply it is in the shower, placing one foot on the edge of the tub and using two fingers to insert the yogurt vaginally and around the vulva. Do not place fingers back in the yogurt after applying; rather place the appropriate amount (2 to 3 tbs) in a small container. The yogurt should be left on for 3 to 5 minutes, and then rinsed off, repeating up to two times daily depending upon the severity of the infection and irritation. Repeat for up to 2 weeks, although treatment is often effective within several days.

Additional Therapies

Boric Acid

Boric acid is a common OTC treatment for VVC and RVVC that is both self-prescribed and recommended by health practitioners.1,19,52 Although it has not been widely studied, four studies have shown positive outcomes, even compared with conventional antifungal therapy, and it is considered an effective therapy for the treatment of vaginal candidiasis.1,18,19,52,53 In one study, 92 women with chronic mycotic vaginal infections were followed with microscopic examination of the vaginal discharge during prolonged therapy with antifungal agents and boric acid. A microscopic picture unique to chronic mycotic vaginitis was observed, representing the cytologic reaction of the mucous membrane to chronic yeast infection. This diagnostic tool proved extremely effective in detecting both symptomatic and residual, subclinical mycotic infection and provided a highly predictive measure of the probability of relapse. The ineffectiveness of conventional antifungal agents appeared to be the main reason for chronic mycotic infections. In contrast, boric acid was effective in curing 98% of the patients who had previously failed to respond to the most commonly used antifungal agents and was clearly indicated as the treatment of choice for prophylaxis.53 In a double-blinded, randomized study, 108 VVC-positive college students used boric acid or Nystatin capsules once daily for 2 weeks. Boric acid cure rates were 92% at 7 to 10 days posttreatment and 72% at 30 days, a statistically significant improvement over the Nystatin capsules, which only had a cure rate of 64% at 7 to 10 days posttreatment, and 50% at 30 days posttreatment.54 In a case series of 40 patients with vulvovaginitis, 95% of patients remained symptom-free at 30 days post–boric acid treatment, and in another study, boric acid was tested against an azole-resistant strain of yeast, more commonly seen in women with recurrent yeast infections and yielded clinical improvement occurred in 81% of cases, with mycological eradication in 77% of the women.19,55,56 The standard recommended dose and application is 600 mg of boric acid placed in a size “0” gelatin capsule and inserted vaginally. For acute treatment, one capsule is inserted nightly for 14 days, followed by a maintenance treatment of twice weekly insertion.19,53 Some women report mild to moderate burning as the capsule dissolves. If intercourse occurs during the treatment period, males may report dyspareunia.19 Serious side effects have not been reported from treatment.53 Boric acid, available in drug stores, can be considered a safe, effective, accessible, and affordable treatment for vaginal candidiasis.

General Suggestions

Reducing exposure to the personal, sexual, chemical, and allergenic factors described in the preceding can be beneficial in preventing and reducing vulvovaginitis and infection. Wearing clean cotton underwear or “breathable” fabrics, changing underwear more often if there is copious vaginal discharge or dampness, sleeping without underwear, wearing loose-fitting pants, and observing hand-washing before and after genital contact may reduce the incidence and frequency of vulvovaginitis.52 Wearing a thong may cause irritation or facilitate the transmission of anorectal organism to the vulvovaginal area. Regular bathing and showering with gentle soap, keeping the vulvar area dry, and regular use of sitz baths also may be helpful, the latter particularly in candidal vulvovaginitis.

TREATMENT SUMMARY FOR VULVOVAGINITIS

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree