Urologic and Gastrointestinal Injuries

Over the last 200 years, the maternal morbidity and mortality associated with operative deliveries has been substantially reduced. In particular, mortality rates associated with cesarean section have been reduced from nearly 100 percent prior to the turn of the twentieth century to about 120/100,000 cesarean births (Sachs and coworkers, 1988). As morbidity and mortality associated with abdominal delivery have decreased, there has been a shift from difficult operative vaginal deliveries to cesarean sections. With this change there has been a substantial reduction in the injuries to the lower urinary tract. The frequency of urologic injuries associated with cesarean section has been studied by a number of investigators. Eisenkop and colleagues (1982) reported their experiences at Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center over a 5-year period. The incidence of injuries to the bladder and ureter was 0.3 percent and 0.1 percent, respectively. Virtually all bowel injuries associated with childbirth are to the anal sphincter and lower rectum during vaginal deliveries. Bowel injuries during cesarean section are rare.

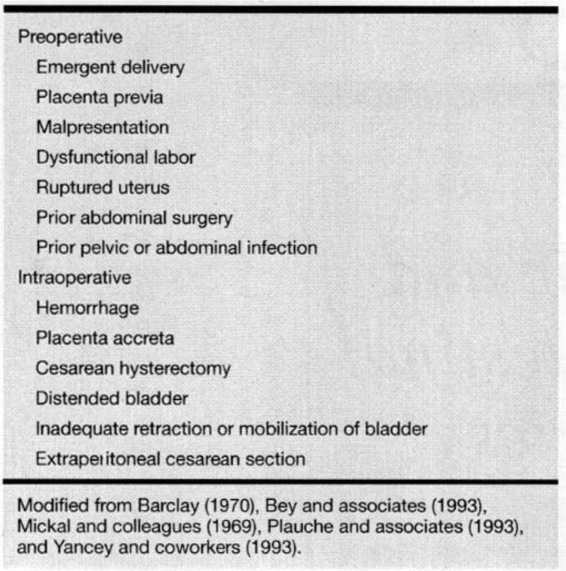

Risk factors associated with injuries to either the gastrointestinal or urinary tracts are listed in Table 25-1. In general, these factors can be divided into those that are identifiable preoperatively and those that are identifiable intraoperatively. Those factors that carry the greatest risk include emergent cesarean section, prior abdominal surgery, hemorrhage, and cesarean hysterectomy. Risk factors that are identifiable preoperatively should be used to the surgeon’s advantage to try to compensate for those intraoperative factors that ensue. Intraoperative risk factors result in poor exposure of the pelvic anatomy either directly or indirectly through hemorrhage. The wise surgeon will use this information to select the best anesthetic, incision type (vertical vs. Pfannenstiel), and surgical assistant to minimize the risk to the patient. During an emergency cesarean section the surgeon should take great care to maintain methodical technique and not let “the heat of the moment” overcome good judgment. Surgeons performing operative deliveries should be aware of risk factors for these injuries. Identification of the woman at risk may prevent injuries, and when prevention is not possible, may prompt recognition and repair of injuries to the gastrointestinal and urinary tracts, which substantially reduces surgical morbidity.

TABLE 25-1. Risk Factors for Urologic and Gastrointestinal Injuries During Cesarean Section Deliveries

UROLOGIC INJURIES

The anatomic and physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy place the urinary tract at greater risk for injury during cesarean section. Elevation of the uterus results in bladder elevation, and uterine dextrorotation brings the left ureter more into the operative field. Furthermore, hydronephrosis, which is characteristic of pregnancy, along with the marked dilatation of vessels in the infundibulopelvic ligament, place the ureter at greater risk for injury during retroperitoneal dissections and isolation of the infundibulopelvic ligament. Intraoperative recognition of urinary tract injuries with immediate repair results in very little morbidity (Blandy, 1991; Brubaker, 1991; Faricy, 1978; Neuman, 1991; and their associates).

BLADDER INJURIES

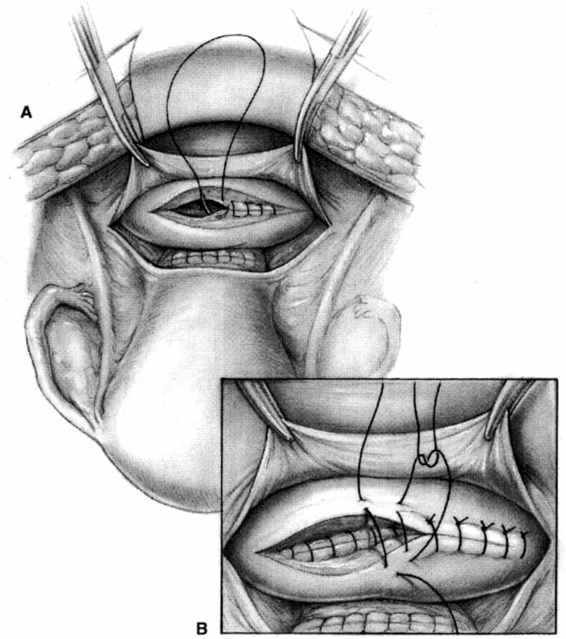

The bladder is the most common nonreproductive organ injured during obstetric events. Eisenkop and colleagues (1982) reported an incidence of cystotomy of 0.2 percent in primary cesarean sections and 0.6 percent of repeat cesarean sections. These injuries can be associated with either blunt or sharp dissection of the bladder flap, extensions of the uterine incision, or uterine rupture (Hsu and colleagues, 1992). Many of these injuries can be prevented with careful dissection and adequate development of the bladder flap prior to making the uterine incision. Fortunately, most injuries are to the dome of the bladder and usually do not involve the trigone. Intraoperative diagnosis can be confirmed by filling the bladder with dilute sterile milk. Dilute indigo carmine also may be used; however, if it is too concentrated the tissues will stain dark blue and it becomes difficult to identify the anatomy. If it is too dilute, there is not enough contrast to identify the injury. After the injury is identified, the bladder mucosa should be inspected to ensure that the injury does not involve trigone or ureteral orifices. If these structures are clearly separate from the injury, the cystotomy can be closed in two layers by using 3-0 polyglycolic acid or chromic suture in a running fashion on the mucosa, followed by a second layer of imbricating 2-0 or 3-0 polyglycolic acid or chromic suture in an interrupted fashion (Fig. 25-1). In case of a bladder injury near the trigone, a cystotomy enables identification of the ureteral orifices and facilitates stent placement. A cystotomy performed in the midplane gives excellent exposure, and the original incidental cystotomy may be incorporated in the closure of the cystotomy. If the trigone is involved, the surgeon should be careful not to disrupt the ureteral orifices. If the injury is close to either ureter, stents should be placed to maintain ureteral patency. Bladder lacerations involving one or both ureteral orifices such that proper repair without further ureteral injury or obstruction is impossible will require ureteroneocystostomy.

FIGURE 25-1. Cystotomy repair. A. The first layer is a continuous running mucosal suture with a 3-0 absorbable suture. B. The second layer is an imbricating interrupted layer of 2-0 absorbable sutures.

After the repair is complete, the bladder is filled passively with 250–300 mL of dilute sterile milk. Small sites of extravasation can be reinforced with imbricating sutures. Large defects require revision of the closure. After the bladder returns to its normal anatomic location the relative location of suture lines on all organs should be inspected. Placement of the suture line in close proximity to another suture line will increase the risk of fistula formation. An omental J-lap can be quickly and safely interposed between suture lines to avoid this risk. An omental J-flap is created by dissecting the omentum off the transverse colon starting at the hepatic flexure and continuing toward the midline. Dissecting along the greater curvature of the stomach provides greater length. Dissection is complete when adequate length is obtained. Preservation of the blood supply from the left side of the stomach will improve blood supply to the region. The omentum may be fixed in place with one or two strategically placed stitches with 2-0 or 3-0 polyglycolic acid or chromic suture.

Postoperatively, the bladder is drained either through a Foley or a suprapubic catheter for 7–10 days. Morbidity associated with intraoperative recognition of bladder injury and proper repair is minimal. Persistent extravasation of urine will lead to fistula formation and prolonged drainage minimizes this risk. Factors that impair healing should be considered when deciding when to remove the Foley catheter.

URETERAL INJURIES

The incidence of ureteral injury complicating cesarean delivery is 0.1 percent, and is most commonly associated with extension of the uterine incision or attempted control of hemorrhage. The incidence rises to 0.2–0.6 percent when cesarean hysterectomy is performed (Barclay, 1970; Mickal and colleagues, 1969). Diagnosis is confirmed by injecting 5–10 mL of indigo carmine dye intravenously and observing the ureters for evidence of dye extravasation. It may be 10 minutes or more before the dye can be seen in the bladder or Foley catheter, depending on the rate of urine production. Increased hydration and furosemide will decrease this time. Anticipation of the need to evaluate the integrity of the urinary tract is the best way to deal with surgeon impatience. If a cystotomy is performed, the dye should enter the bladder through both ureteral orifices almost simultaneously. Significant delay in the appearance of dye from one ureter relative to the other may signify a partial obstruction. An alternative to waiting for dye excretion is direct injection of indigo carmine dye into the ureter above the suspected injury with a fine-gauge needle (O’Leary and O’Leary, 1968). Repair of ureteral injuries is dependent upon the type of injury and location.

DISTAL URETERAL INJURIES. Crush injuries to the distal ureter and obstructions resulting from suture ligation or ureteral kinking may be alleviated with removal of the clamps or sutures causing the obstruction and placement of a ureteral stent. Stents can be placed either cystoscopically or through a cystotomy incision. Intraoperatively, cystotomy is usually more convenient and should be performed in the dome of the bladder. A double-J, 6–8-French ureteral stent is placed over a guidewire. The guidewire is threaded retrograde through the ureteral orifice to the renal pelvis. The stent is passed over the wire into the renal pelvis and the guidewire is removed, allowing the stent to coil in the renal pelvis and the bladder. The stent should coil in the bladder without excessive length. The cystotomy is then repaired as outlined previously. An intraoperative abdominal x-ray will confirm proper placement. Postoperatively, the bladder is drained for 7–10 days, and the ureteral stent can be removed in 3–6 weeks via cystoscopy. Prolonged bladder drainage is not necessary if the stents are placed cystoscopically. Women with injuries resulting in devascularization of the ureter, such as crush injuries, should undergo intravenous pyelography before stent removal to evaluate ureteral integrity.

Injuries to the distal third of the ureter are associated with extensions of the uterine incision and attempts to control blood loss. The left ureter is at greater risk because of its more anterior location with dextrorotation of the uterus during pregnancy. Partial or complete transection of the distal third of the ureter is usually best handled by ureteroneocystostomy (Fig. 25-2). Vascularity of the distal ureter can be tenuous and can result in impaired healing. After the injury is identified, the distal portion of the ureter is ligated and the proximal portion is mobilized sufficiently to perform an anastomosis to the bladder without tension. A suture is placed through the distal portion of the ureter. A vertical

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree