Little is known about the natural history of pelvic floor disorders. For instance, not all women with prolapse are symptomatic, and symptoms do not necessarily correlate with physical exam findings.

Pelvic floor disorders such as POP are the indication for more than 300,000 surgeries annually in the United States at a cost of $1 billion. Up to 11% of women have surgery for POP or stress urinary incontinence (SUI) by the age of 80 years. Twenty-nine percent of patients will require repeat surgery.

Anatomy of the bladder: The bladder is both an elastic muscular reservoir and a pump for urination. The urethra serves as the conduit, but micturition requires coordination of urethral and bladder functions. Urethral muscular components which affect urinary continence include an outer layer of striated muscle arranged in a circular pattern (external urethral sphincter [EUS]). Internal to the striated component of the urethral sphincter is a circular layer of smooth muscle, which in turn surrounds a well-developed layer of inner longitudinal muscle (internal urethral sphincter [IUS]). Deep to these layers is a prominent vascular plexus that is believed to contribute to continence by forming a watertight seal via coaptation of the mucosal surfaces. Distally, the fibers of the compressor urethrae pass over the urethra to insert into the urogenital diaphragm near the pubic ramus. Urethral function

is also impacted by the relatively static supportive layer beneath the vesical neck, which provides a backstop against which the urethra is compressed during increased intra-abdominal pressure.

TABLE 31-1 Neuroanatomy of the Bladder and Urethra

Muscle

Innervation

Neurotransmitter Rreceptors

External urethral sphincter (EUS)

Perineal branch of pudendal nerve

Nicotinic acetylcholine

Internal urethral sphincter (IUS)

Sympathetic fibers from hypogastric plexus

Muscarinic acetylcholine, alpha- and betaadrenergic, and others

Detrusor relaxation

Sympathetic fibers

Beta-adrenergic

Detrusor contraction

Parasympathetic fibers from sacral plexus

Muscarinic acetylcholine

Adapted from de Groat WC. Integrative control of the lower urinary tract: preclinical perspective. Br J Pharmacol 2006;147(S2):S25-S40.

Neurophysiology of the lower urinary tract (Table 31-1)

Micturition cycle: The bladder has two basic functions: storing urine (sympathetic) and, when socially appropriate, evacuating urine (parasympathetic). Bladder filling occurs with relaxation of the detrusor muscle and contraction of the IUS. With bladder filling, afferent activity via baroreceptors triggers the storage reflex to maintain sympathetic tone in the IUS. When the bladder is full, afferent activity in the pelvic nerve stimulates the micturition reflex.

Anatomy of the pelvic floor: See Chapter 26.

Anatomy of the anal sphincters: The internal anal sphincter (IAS) is smooth muscle innervated by the parasympathetic nervous system and is tonically contracted, whereas the external anal sphincter (EAS) is striated muscle innervated by sympathetic nervous system and can only sustain voluntary contraction for a few minutes. The puborectalis muscle and the EAS function together.

Anal continence is the end result of orchestrated functioning of the cerebral cortex, along with sensory and motor fibers innervating the colon, rectum, anus, and pelvic floor. The distension of the rectum by stool entering from the sigmoid colon causes the urge to defecate, and the IAS to relax while the EAS contracts (known as the rectoanal inhibitory reflex). At an appropriate time, the anorectal angle is straightened, the rectum is contracted, the EAS is inhibited, and the rectal contents are released. Rectal filling beyond 300 mL results in the sensation of urgency.

Most women with pelvic floor disorders have multiple risk factors.

Race: Epidemiologic studies have not consistently demonstrated any racial or ethnic difference in the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders. Some studies address variables such as knowledge and perception about pelvic floor disorders and access to care.

Age: The prevalence of POP, UI, and AI has been observed to increase with age. Although bladder capacity, ability to postpone voiding, bladder compliance, and urinary flow rate decrease with age in both sexes, overactive bladder symptoms and incontinence are not a normal result of aging.

Hypoestrogenism: Estrogen deficiency can result in urogenital atrophy with resultant thinning of the submucosa and a decrease in the functional urethral length. The literature is unclear as to the association of estrogen deficiency and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).

Parity and childbirth: The incidence of pelvic floor disorders such as UI, POP, and AI are higher among parous than nulliparous women. Damage to the pelvic tissues during a vaginal delivery is thought to be a key factor in the development of these disorders, which may be more significant with operative delivery. In addition, lacerations of the internal and external anal sphincters at the time of vaginal delivery can result in impaired anal sphincter strength and AI.

Underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, obesity, dementia, stroke, depression, Parkinson, or multiple sclerosis may be risk factors for pelvic floor disorders.

Previous pelvic surgery may increase the risk of pelvic floor disorders.

Pharmacologic agents, such as diuretics, caffeine, anticholinergics, and alphaadrenergic blockers, may affect urinary tract function.

Chronically increased intra-abdominal pressure (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], chronic constipation, obesity) may be a risk factor for LUTS and POP.

Any patient evaluation in urogynecology should include a thorough medical, surgical, gynecologic, and obstetric history. The clinical evaluation should elicit the patient’s complaints, defining the location and severity of support defects and evaluating other potential etiologies of pelvic floor symptoms. Pelvic floor defects are rarely localized to one anatomic compartment and are often multifactorial. The clinician should gain an understanding of the duration, frequency, severity, precipitating factors, social impact, effect on hygiene, effect on quality of life, and measures used to avoid bothersome symptoms. Patients may be reluctant to volunteer symptoms of pelvic floor disorders.

Symptoms of pelvic floor disorders including LUTS, POP, or AI can be grouped into four main categories:

Bulge: Patients may complain of pelvic pressure, heaviness, protruding tissues, or bulging.

Voiding dysfunction or incontinence: Patients may complain of day- or nighttime involuntary loss of urine, with or without Valsalva or urgency. Patients may have symptoms associated with urethral obstruction secondary to prolapse, especially with anterior compartment prolapse. They may have urinary hesitancy, incomplete emptying, or the need for vaginal splinting or Valsalva before successfully passing urine. Patients may have associated recurrent or persistent urinary tract infections (UTIs) secondary to urinary retention. They may also report irritative voiding symptoms such as urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence. They may demonstrate occult stress incontinence when prolapse is reduced (e.g., after surgery or with pessary placement).

Defecatory dysfunction: Patients may have symptoms of defecatory dysfunction, especially with apical and posterior compartment prolapse. These include symptoms of incomplete defecation, required splinting or straining, constipation, and pain with defecation. Women with anal sphincter defects may present with AI of flatus, liquid, or formed stool.

Altered sexual functioning and body image: Patients may complain of dyspareunia, avoidance of intercourse, decreased libido, and decreased self-image.

There are many validated and reliable questionnaires that can aid in eliciting a symptom history from patients, such as the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory, the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire, and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire.

Urinary diary: The patient records the volume and frequency of fluid intake and voiding as well as symptoms of frequency and urgency and episodes of incontinence over 24 hours, ideally for 3 days. This will allow the practitioner to better characterize the patient’s symptoms as well as enable the patient to use it as a therapeutic tool to modify her behavior.

A comprehensive physical examination should be performed at the first visit, including:

A screening neurologic examination to evaluate overall mental status and sensory and motor function of the lower extremities.

A pelvic exam, including a systematic evaluation of all components of the pelvic floor, including innervation, vulvar architecture, muscular and connective tissue support, and perineal scars. Particular attention should be given to urethral anatomy and hypermobility (see Q-tip test in the succeeding text).

Speculum exam, using a Sims speculum or the posterior blade of a Graves speculum, is helpful to assess support, the presence of scarring, and any associated findings.

The bimanual exam investigates the location, size, and tenderness of the bladder, uterus, cervix, and adnexa. The strength of the levator ani muscles is assessed by placing one or two fingers in the vagina and asking the patient to squeeze. The firm muscular sling of the posterior puborectalis should be readily palpable.

Sacral nerve roots and the sacral reflex (also called the bulbocavernosus reflex) should be evaluated. When the clitoris or the area lateral to the anus is lightly scratched, an ipsilateral contraction of the anal sphincter should occur. In older patients, this reflex may be absent. In obese patients, this reflex may be difficult to evaluate.

The Q-tip test evaluates urethral support. A cotton swab is placed in the urethra to the level of the urethrovesical junction, and the change in axis from rest to strain is measured to assess urethral hypermobility. Angular measurements of >30 degrees are generally considered hypermobile. Urethral hypermobility is thought to occur due to loss of integrity of the fibromuscular tissue that supports the bladder neck and urethra.

A rectal examination can further assess pelvic pathology as well as evaluate the presence of fecal impaction. The exam should include an inspection of the perineal area for evidence of skin irritation or stool on the skin as well as digital examination of the anal sphincter for resting and squeeze pressure. One should also note the presence of a gaping anus or scarring.

To evaluate POP, four specific anatomic components should be assessed: (a) anterior vaginal wall, (b) uterus and vaginal apex, (c) posterior vaginal wall, and (d) presence or absence of an enterocele. These compartments should be assessed with a standardized

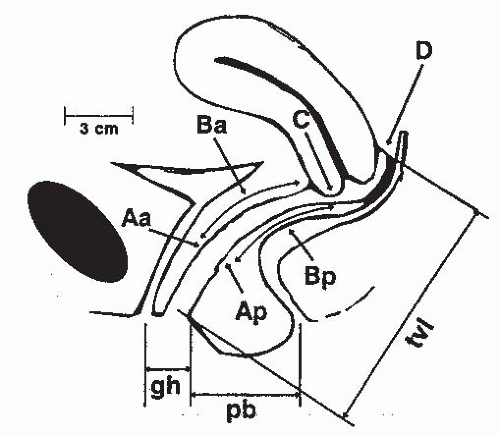

system. The International Continence Society (ICS), American Urogynecologic Society, Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, and the National Institutes of Health recommend the standardized Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system for grading support defects (Fig. 31-1). Many staging systems exist, but the POPQ system is widely accepted and published, easily learned, and reproducible. Additionally, pelvic muscle function can be assessed using scales such as Brink.

The POPQ uses the hymen as a fixed point of reference and describes six specific topographic points on the vaginal walls (Aa, Ba, C, D, Bp, and Ap) and three distances (genital hiatus, perineal body, total vaginal length).

The prolapse of each segment is measured in centimeters during Valsalva relative to the hymenal ring with points inside the vagina reported as negative numbers and outside as positive. The numeric values are then translated to a stage as described in Table 31-2.

The perineal body is normally at the level of the ischial tuberosities. Descent of >2 cm below this level with flattening of the intergluteal sulcus indicates perineal descent.

To fully evaluate POP, the patient may need to perform a Valsalva maneuver in lithotomy or strain while seated or standing while being examined by the provider. Pelvic floor muscle strength can be assessed, as outlined earlier.

Examination of the anterior vaginal wall should include evaluation of the support of the urethra. With a speculum (or half of the speculum) used to depress the posterior vaginal wall, the patient is asked to strain, and any descent of the anterior vaginal wall is noted.

Figure 31-1. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system components and anatomic reference points. For explanation of terms, see Table 31-2. (From Bent AE, Ostergard DR, Cundiff GW, et al, eds. Ostergard’s Urogynecology and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003:97, with permission.)

TABLE 31-2 Description and Staging of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System

Point/Distance

Description

Aa

Midline anterior vaginal wall, 3 cm proximal to the urethral meatus

Ba

Anterior vaginal wall, most distal point between Aa and anterior fornix (cuff)

C

Edge of the cervix (or vaginal cuff in posthysterectomy patients)

D

Posterior fornix. Not used in patients with hysterectomy

Ap

Midline posterior vaginal wall, 3 cm proximal to the hymenal ring

Bp

Posterior vaginal wall, most distal point between Ap and posterior fornix (cuff)

Genital hiatus

Middle of the urethral meatus to posterior midline hymenal ring

Perineal body

Posterior margin of genital hiatus to the middle anus

Total vaginal length

Greatest depth of vagina with C or D reduced to its normal position

Staging of the POPQ system

Stage 0

Perfect support; Aa, Ap at −3. C or D within 2 cm of TVL from introitus.

Stage 1

Most distal portion of prolapse is −1 (or more negative) proximal to introitus.

Stage 2

Most distal portion within 1 cm of the hymenal ring (between −1 and +1).

Stage 3

Most distal portion > +1 cm but <(TVL-2) cm distal to introitus.

Stage 4

Complete prolapse; most distal portion between TVL and (TVL-2) cm distal to introitus.

POPQ, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification; TVL, total vaginal length.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree