when urine osmolality is low, or when analysis is delayed. Dipstick analysis is most predictive for UTI when the results are positive for bacteria (positive nitrites) and the presence of leukocyte esterase is detected; in these instances, they have a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 82% for UTI.4 Some foods may produce false-positive nitrite tests. A negative dipstick, in the presence of significant UTI symptoms, does not rule out an infection and empiric therapy, or further evaluation may be warranted.

TABLE 15.1 First-Line Therapy for Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

cells in the urinary tract, thereby inhibiting infection. These compounds do not prevent infection by urinary acidification as is commonly believed. Although some studies show cranberry juice may help decrease the number of symptomatic UTIs, the data has not definitively demonstrated efficacy, although there is little likelihood of harm in its use for this purpose.29,30 Some research leads to the recommendation of drinking at least one to two cups of cranberry juice daily or taking at least 300 to 400 mg in tablet form twice daily.30

TABLE 15.2 Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Regimens for Women With Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

indwelling catheters, falls and fractures if the woman slips on floor wet with urine, and sleep deprivation if nocturia is present. Other comorbid conditions, medications, and factors influencing patient function may cause or even worsen UI, either transiently or chronically (see Table 15.3 for potential causes or contributors to UI).

TABLE 15.3 Identification and Management of Reversible Conditions That Cause or Contribute to Urinary Incontinence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

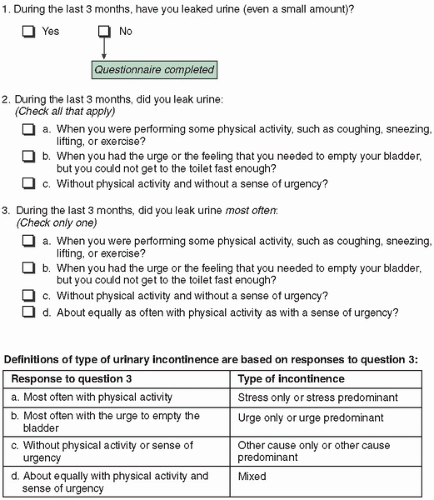

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is involuntary UI with effort or physical exertion, such as sneezing, coughing, or activity, although it may occur without provocation if there is significant damage to the urethral sphincter. SUI occurs when an increase in intraadominal pressure overcomes the urethral sphincter mechanisms that keep the sphincter shut; hence, there is a loss of urine in the absence of a bladder contraction. This is the most common cause of UI in younger women and often coexists with urge incontinence in middle-aged or older women.51

Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) is the involuntary loss of urine associated with a strong urge to void, even when the bladder is not full. Its etiology is presumed to be uninhibited bladder contractions, also referred to as detrusor overactivity.52 This is most likely not the only etiology, however, because detrusor overactivity may be found in continent individuals as well.

TABLE 15.4 Differential Diagnosis of Urinary Incontinence

Stress urinary incontinence

Hypermobility (anatomic)

Intrinsic sphincter deficiency

Overactive bladder

Motor urge incontinence

Sensory urge incontinence

Detrusor dyssynergia

Detrusor hyperreflexia

Detrusor hyperactivity with incomplete contractility

Mixed incontinence

Bypass of the continence mechanism

Fistula

Diverticulum

Ectopic ureter

Overflow incontinence

Functional

Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) is involuntary UI associated with urgency and also with physical exertion; it is believed to occur when there is coexisting urgency and stress incontinence.

Nocturnal enuresis is involuntary urine loss during sleep.

Continuous UI is continuous involuntary urine loss and may be seen with either bladder outlet obstruction and/or impaired detrusor contractility. Patients may be unaware of the leakage at all. Although referred to as “overflow incontinence” in the past, the preferred term mentioned earlier is best to use along with any known associated pathophysiology.

Postural UI is involuntary loss of urine associated with change of body position (rising from a seated or lying position).

Insensible UI is when UI occurs but the woman is unaware of how it occurred.

Coital UI is UI with coitus, occurring with penetration or intromission or UI occurring at orgasm.

gel, into the cleansed urethral meatus to the level of the urethrovesical junction (UVJ) and asking the patient to strain (Q-tip test). The straining angle of the arm of the tail compared with the horizontal axis is the measurement of urethral or bladder neck mobility. A straining angle greater than 30 degrees is indicative of poor anatomic support of the UVJ and urethral hypermobility but does not necessarily confirm the diagnosis of SUI.

TABLE 15.5 Medications That May Cause or Worsen Urinary Incontinence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

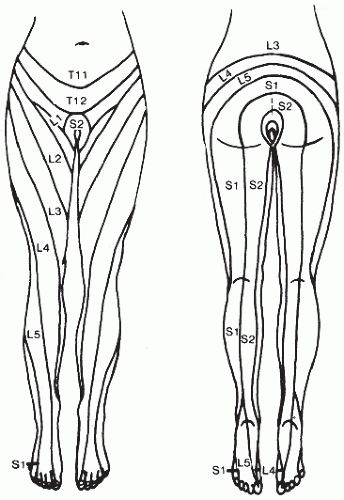

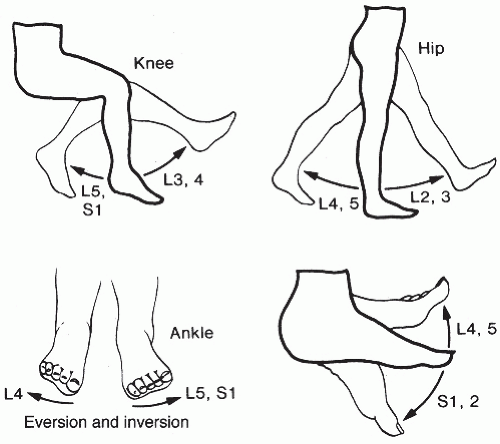

detrusor overactivity; examination of such patients should include assessment of lateral rotation and flexion of the neck, inspection of the hands for interosseous muscle wasting, and determination if a Babinski reflex is present because these would suggest cervical changes and resultant nerve impairment.

FIGURE 15.2 Testing of motor strength. (From Ostergard DR, Bent AK. Urogynecology and Urodynamics: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1996:682, with permission.) |

urethral closure pressure will result in urinary leakage, and this can be due to either decreases in urethra closure pressure caused by urethral dysfunction or increases in bladder pressure caused by detrusor dysfunction or a combination of both. There are a multitude of clinical tests measuring various properties of the lower urinary tract that have been developed—from simple office cystometrics to multichannel video studies.37,59 For many, urodynamic testing has become routine practice, but its role in the evaluation of incontinence for all is controversial. It is expensive, requires specialized equipment and training, does not always correlate with symptoms, and is invasive (Table 15.6).60,61 Although it is associated with about a 2% risk of UTI, prophylactic antibiotics are not necessary.62 Studies trying to demonstrate better treatment outcomes in instances of UI based on urodynamic testing results compared to treatment based on history and physical examination alone have been mixed.63,64 One meta-analysis that included 1000 women with clinical symptoms of stress incontinence showed that when compared against a urodynamic diagnosis, testing was 91% sensitive but only 51% specific in diagnosing pure stress incontinence. The same analysis showed that for urge

incontinence, history alone was 73% sensitive but only 55% specific.65 For these reasons, clinicians should be aware of what diagnostic information urodynamic tests can and cannot provide, its limitations and issues, and how to accurately interpret or even studies that seek to establish their efficacy.66

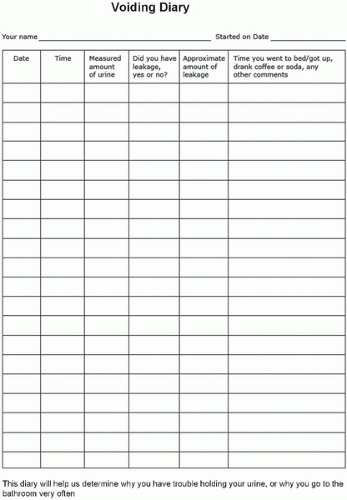

FIGURE 15.4 Example of urolog. (From DuBeau CE. Treatment of urinary incontinence. http://www.uptodate.com. Updated October 2011. Accessed December 2, 2013.) |

TABLE 15.6 Indications for Urodynamic Testing | |

|---|---|

|

does not have a medical contraindication would seem to be all that would be necessary to initiate therapy. There are no randomized controlled trials showing prospective urodynamic testing improves treatment outcomes for either SUI or OAB.67, 68, 69 The testing is also invasive, may be embarrassing for patients, and not cost-effective to apply as a universal policy. Experts mainly agree it is not necessary to perform urodynamic testing on patients prior to instituting conservative management.70

TABLE 15.7 Patients in Whom Postvoid Residual Measurement May Be Helpful | |

|---|---|

|

The first sensation of bladder filling

A desire to void but one that can be tolerated

Urgent need to void

Maximum capacity; patient can no longer avoid micturition

TABLE 15.8 Known Issues Affecting Urodynamic Testing Results and/or Interpretation of Results or Studies | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree