18.1 Urinary tract infections and malformations

Urinary tract infections

Epidemiology

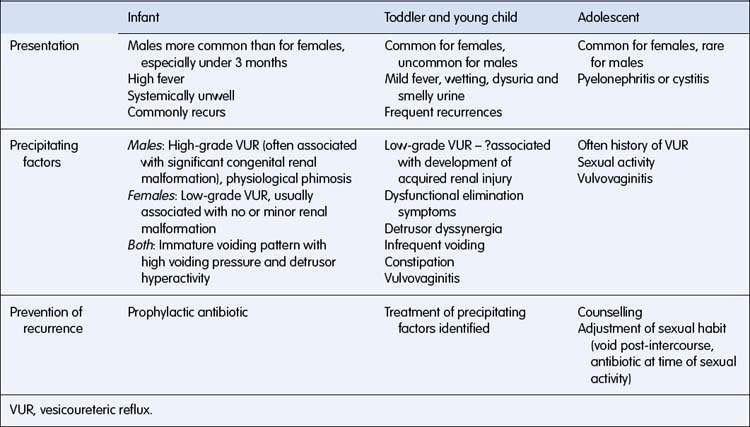

Epidemiological studies have shown that 2% of boys and 8% of girls have had a UTI by the age of 7 years; 75% of UTIs occur under the age of 1 year in males and 50% under the age of 1 year in females. The prevalence of UTI in febrile infants under the age of 3 months presenting to emergency departments is 20–30%, and boys outnumber girls. After the age of 3 months, the prevalence of UTI in febrile children falls to around 8% in female and 2% in male children. The incidence of UTI in uncircumcised boys is 4–10 times that in circumcised boys in the first 3 months of life. Common clinical patterns of UTI are described in Table 18.1.1.

Diagnosis

The frequency of symptoms of UTI in a recent series of 304 children less than 5 years of age presenting to a Sydney hospital emergency department is listed in Table 18.1.2. The presentation varies with age because of the developmental status of the child. Although a wide range of symptoms can occur, an infant will probably have an acute illness with fever and vomiting or a chronic illness with failure to thrive, reflecting the systemic response to infection at this age. The preschool child, who has usually achieved continence, will often show wetting or frequency, complain of generalized abdominal pain and sometimes indicate dysuria. The teenage girl will usually present with symptoms of cystitis (fever, frequency, dysuria, strangury and accurately localized pain) or pyelonephritis (fever, often with rigor, and loin pain and tenderness). At any age, symptoms of fever, vomiting and systemic unwellness occur with pyelonephritis.

Table 18.1.2 Frequency of symptoms in children under 5 years with symptomatic urinary tract infections

| Symptom | % |

|---|---|

| History of fever | 79.6 |

| Axillary temperature > 37.5 °C | 59.5 |

| Irritability | 52.3 |

| Anorexia | 48.7 |

| Malaise/lethargy | 44.4 |

| Vomiting | 41.8 |

| Diarrhoea | 20.7 |

| Dysuria | 14.8 |

| Offensive urine | 13.2 |

| Abdominal pain | 13.2 |

| Family member with past history of UTI* | 11.2 |

| Previous unexplained febrile episodes | 10.5 |

| Frequency | 9.5 |

| Urinary incontinence† | 6.6 |

| Macroscopic haematuria | 6.6 |

| Febrile convulsion | 4.6 |

UTI, urinary tract infection.

† Defined as a noticeable increase in the frequency of daytime wetting.

Source: Craig JC, Irwig LM, Knight JF et al 1998 J Paediatr Child Health 34:154–159.

Urinalysis and microscopy

Dipstick testing

• Positive leukocyte esterase is a reasonably sensitive test but is not at all specific for urinary tract infection (UTI).

• Positive nitrites are less sensitive but quite specific for UTI.

• Negative testing for leukocyte esterase and nitrites does not exclude UTI, especially in babies. Some 10% of babies with UTI will have negative dipstick testing.

• Always send urine for culture if UTI is suspected.

• Negative dipstick testing may reasonably be used in making the decision to withhold antibiotics from children over 3 years of age while awaiting urine culture results.

Initial treatment

Once the urine culture has been obtained, a decision on acute treatment must be made. Intravenous therapy is required if: the child is systemically unwell (dehydrated, signs of septic shock such as hypotension, tachycardia and decreased conscious state); vomiting and unable to retain oral medications; and in infants under the age of 6 months generally, because oral absorption is unreliable. In the child in whom an infection is likely on the basis of urinalysis and presentation, and the child is reasonably well (generally older and not vomiting), oral antibiotics may be commenced, with review once the culture is through in 24–48 hours. In the child in whom urinary infection is a possibility and the child is not unwell, culture results should be awaited before starting treatment. The intravenous antibiotics and oral antibiotics used acutely are listed in Table 18.1.4. Intravenous antibiotics are usually ceased within 2–3 days once culture results have been obtained and the child has improved clinically. Acute treatment is completed with oral antibiotics, usually of 5 days’ duration.

Table 18.1.4 Antibiotic treatment of urinary tract infection

| Antibiotic | Dose | Organisms sensitive* (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute | ||

| Intravenous | ||

| (sick, < 6 months old, pyelonephritis) | ||

| 1. Benzyl penicillin | 50 mg/kg (max. dose 2 g) 6 hourly | Covers Enterococcus |

| and | ||

| 2. Gentamicin | 7.5 mg/kg daily for age < 10 years, 6 mg/kg daily for age > 10 years (max. dose 360 mg) Monitoring: trough level < 1 mg/L taken on 3 rd day and serum creatinine 3 rd day | ≥ 95 |

| Oral | ||

| Trimethoprim | 4 mg/kg (max. dose 150 mg) 12 hourly | ≥ 85 |

| or | ||

| Co-trimoxazole | (40 mg/200 mg per 5 mL) | ≥ 85 |

| 0.5 mL/kg (max. dose 20 mL) 12 hourly | ||

| or | ||

| Cefalexin | 15 mg/kg (max. dose 500 mg) 8 hourly | 95 |

| or | ||

| Augmentin† | 10–25 mg/kg 8 hourly | 95 |

| Prophylactic | ||

| Co-trimoxazole | (40 mg/200 mg per 5 mL) | ≥ 85 |

| 0.25 mL/kg nightly | ||

| Nitrofurantoin | 1–2 mg/kg nightly | ≥ 85 |

| Cefalexin‡ | 5 mg/kg nightly | ≥ 95 |

* Percentage of bacteria causing urinary tract infection diagnosed in the emergency department of major Australian hospitals that are sensitive to antibiotics.

† Amoxicillin alone only covers 60% of organisms encountered, so Augmentin is preferred.

‡ The suspension forms of the cephalosporins and penicillins lose activity after a few weeks.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree