15 Urinary problems

Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

How common are UTIs?

A total of 10–15% of healthy non-pregnant women will suffer from acute uncomplicated cystitis each year1 with the highest incidence (17.5%) reported by women aged 18 to 24 years. By age 24, one-third of women will have at least one physician-diagnosed UTI that was treated with prescription medication.1 Some 12% of women with an initial infection and 48% of those with recurrent infections will have a further episode in the same year.2

What are the classic symptoms and signs?

Classically, women present with urinary frequency, urgency and dysuria. Dysuria without vaginal discharge or irritation has a positive predictive value of 77% for a positive urine culture.3 Affected patients may complain of pelvic discomfort pre- and post-voiding, passing small quantities of urine and sometimes of haematuria. Some may have suprapubic tenderness or pain.

Is there anything else that it could be?

In about 50% of women who present with urinary symptoms, there is no bacteriuria. These women nevertheless present with dysuria, frequency and urgency.4 Pyuria may be present or absent. They are said to have acute urethral syndrome, or interstitial cystitis or irritable bladder.

Other causes of dysuria and frequency include:

Are there any factors that predispose to UTIs?

When providing patient education about UTIs, there are a number of predisposing factors1,5,6,7–9 that should be highlighted, the strongest of which, in young women, is recent sexual activity (the relative odds of acute cystitis increase by a factor of 60 during the 48 hours after sexual intercourse).10 It is important to inform women of the risk factors, so that they can understand how their own behaviour is related to the onset of UTIs. These factors are listed in Box 15.1. GPs should also be aware of factors that may lead to a more complicated situation, such as abnormalities of urinary tract function (for example, indwelling catheter, neuropathic bladder, vesicoureteric reflux, outflow obstruction, other anatomical abnormalities), previous urinary tract surgery and states of immunocompromise, and neurological disorders. Pregnant women are also at increased risk of pyelonephritis associated with the relative ureteral obstruction during gestation. Risk factors for UTI in postmenopausal women include recurrent UTI, bladder prolapse or cystocele, and increased post-void residual urine.11

In a general practice population, what are the common organisms responsible for UTIs?

Box 15.2 lists the common organisms responsible for UTIs in a general practice population. Approximately 80% are caused by E. coli and 13% by Staphyococcus saprophyticus.12

What should a GP do when a woman presents with symptoms of a UTI?

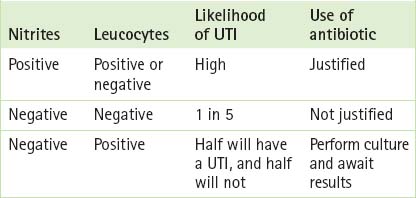

A mid-stream specimen of urine can be tested either by a urine dipstick or by sending the sample to a laboratory for microscopy and culture. Urine microscopy and culture has long been the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis of UTIs but it is expensive and slow to produce a result. Dipstick testing, on the other hand, can be performed on the spot by a GP or nurse. When it shows the presence of either leucocyte esterase or nitrites, it is highly predictive of a positive urine culture (whereas absence of either finding markedly reduces the likelihood of infection),13 and it has been found to be a fairly reliable way to diagnose UTIs. It is important, however, to undertake urine culture if an accurate diagnosis is needed or in order to select an effective antimicrobial (as in pregnancy, treatment failure or immunocompromise). Box 15.3 (p 286) outlines the tests commonly carried out by dipstick testing and Table 15.1 (p 286) advises how to use nitrite and leucocyte testing to guide management in symptomatic female general practice patients.

BOX 15.3 Pertinent findings on urine dipstick analysis in cases of UTI

(From Fitzgerald54)

TABLE 15.1 How to use dipstick testing in the management of women with symptoms of an uncomplicated UTI

Imaging of women with an uncomplicated UTI is not warranted, as there is a low yield of positive results.14 Neither is a single episode of pyelonephritis associated with a clinically significant risk of anatomic abnormality.15 However, in cases of recurrent pyelonephritis imaging with renal ultrasound, intravenous pyelogram or voiding cystourethrogram is indicated.

Should all women presenting with a UTI have urine M&C carried out?

Uncomplicated UTI in non-pregnant women rarely causes severe illness or has significant long-term consequences, and in 50% of patients the condition improves without antimicrobials within 3 days.16 Despite this, empiric treatment of uncomplicated UTIs has been advocated by some as the most cost-effective way to manage UTIs.17,18 Those against empiric management argue on two grounds. First, they say that the urine should be examined to ascertain the diagnosis, limit unnecessary use of antibiotics and identify those patients who may require further investigation. Second, they argue that since uncomplicated UTIs account for a substantial proportion of all prescribed antibiotics, empiric management may lead to rising levels of antibiotic resistance in the community. With regard to this latter argument, however, levels of resistance found in the laboratory may overestimate levels of resistance in general practice.19

What antibiotic choices are there?

Whether treatment is empiric or not, as with all antibiotic prescribing there are a few general rules to follow19:

Box 15.4 outlines the preferred antibiotics for the management of uncomplicated cystitis in non-pregnant women.

BOX 15.4 Antibiotic choices for the management of uncomplicated cystitis

Trimethoprim 300 mg orally daily (3 days for women, 14 days for men)

Cephalexin 500 mg orally 12 hourly (5 days for women, 14 days for men)

Amoxycillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg orally 12 hourly (5 days for women, 14 days for men)

Nitrofurantoin 50 mg orally, 6-hourly (5 days for women, 14 days for men)

If there is proven microbial resistance to other medications use:

Norfloxacin 400 mg orally 12-hourly (3 days for women, 14 days for men)

What is the optimum duration of antibiotic use for women with an uncomplicated UTI?

GPs have a choice of prescribing single-dose, 3- or 5-day, or the more traditional 7- to 14-day therapies for treatment of UTIs. Three-day courses of antibiotics such as trimethoprim are recommended as first-line therapy for lower, uncomplicated UTIs in young women.20,21 One-day treatments are less effective, and longer treatments are associated with increased risk of adverse effects without clinically meaningful improvement in effectiveness.22

In women over 65, short-course treatment (3–6 days) is probably sufficient for treating uncomplicated UTIs.23

Is any follow-up required?

If therapy is clinically successful, the only patients requiring a follow-up examination of the urine for bacteria are pregnant women. The reason for this is that it is only in this group of women that treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is justified, because of the increased risk of pyelonephritis and preterm delivery.24 Asymptomatic bacteriuria is not related to any increase in morbidity or mortality in other patient groups.

What is the risk of recurrence?

Recurrence of dysuria and frequency can either mean failure to eradicate the initial infection or reinfection. Interestingly between 12% and 16% of women receiving empiric therapy for UTI required another course of antibiotics within 4 weeks of their initial symptoms, irrespective of the type or duration of initial antibiotic therapy.25 In these women a longer course of antibiotic should be given rather than using a more sophisticated antibiotic.

What preventive measures or general advice can GPs give to women regarding UTIs?

While popular for treating urinary symptoms such as dysuria and frequency, urine-alkalinising agents such as potassium citrate, sodium citrate and sodium bicarbonate have yet to be proved in terms of their efficacy, over which there is some doubt.26

What measures can be taken in women suffering from recurrent urinary tract infections?

Case control studies6,10 have found no evidence that poor urinary hygiene predisposes women to recurrent infections, and there is no evidence to support giving women specific instructions regarding the frequency of urination, the timing of voiding (postcoital voiding), wiping patterns, douching, the use of hot tubs or the wearing of pantyhose in order to prevent the occurrence of UTIs.

In postmenopausal women with recurrent UTIs, topical vaginal oestrogen can be effective in reducing recurrence.11

In women who have three or more urinary tract infections a year, a GP has several options for management27:

stopped).31 It is important to inform women starting prophylaxis that it works while it is taken but that upon discontinuation UTIs may recur.31

How effective is cranberry juice in the prevention and/or treatment of UTI?

A recent Cochrane review has found that cranberry products significantly reduced the incidence of UTIs at 12 months (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.90) compared with a placebo/control. While they are more effective at reducing the incidence of UTIs in women with recurrent UTIs than in other groups, the optimum dosage or method of administration (e.g. juice, tablets or capsules) has yet to be established.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree