4 Unplanned pregnancy

Reproductive Rights and Abortion

There are three incontrovertible facts about abortion:

Complications from unsafe abortions account for approximately 40% of maternal deaths worldwide.2 Indeed in Australia we have only to look back to 1970 to find that abortion was then the most common cause of maternal death in this country.3 Increasing legal access to abortion is associated with improvement in sexual and reproductive health.4 Conversely, unsafe abortion and related mortality are both highest in countries with narrow grounds for legal abortion5

No society has been able to eliminate induced abortion as an element of fertility control. Induced abortion is the oldest and, according to some health experts, the most widely used method of fertility control.2 It has been estimated that almost two in every five pregnancies (as many as 80 million pregnancies) worldwide are unplanned.6 Some of these are carried to term, while others end in spontaneous or induced abortion. Estimates indicate that 46 million pregnancies are voluntarily terminated each year—27 million legally and 19 million outside the legal system.6 In the latter case, the abortions are often performed by unskilled providers or under unhygienic conditions or both, mainly in developing countries.

Worldwide, an estimated 68,000 women die each year as a consequence of unsafe abortion. Where contraception is inaccessible or of poor quality, many women will seek to terminate unintended pregnancies, despite restrictive laws and lack of adequate abortion services. Prevention of unplanned pregnancies by improving access to quality family planning services must therefore be the highest priority, followed by improving the quality of abortion services and of post-abortion care.7

In most European countries, about two-thirds of women have at least one unintended pregnancy.8 Typically, abortions performed after 12 weeks’ gestation account for fewer than 10% of all pregnancy terminations and are usually done for reasons of fetal abnormality, deteriorating maternal health or, as is more likely to be the case with teenagers, delay in seeking help.9

At what age do women have abortions?

While unplanned pregnancy and abortion occurs more typically in younger women, interestingly over a third of women seeking a termination of pregnancy (TOP) are aged 30 years or over.10 Between 1996 and 2006, there was a 29% increase in the number of women aged 30–50 years having a TOP.11 A lack of effective contraceptive use and inaccurate perceptions of fertility may be an underlying reason for this.12

Many induced abortions are performed on adolescents and young adults. Access to surgical terminations is often limited for these women because of sociocultural barriers. Countries with an open attitude towards teenage sexuality and easy availability of oral contraception have lower abortion rates. Abortion rates are highest in those countries where information and services in family planning are weak and where women’s sexual and reproductive rights are severely contained. In most developed countries, abortion rates vary from about 10 to 30 per 1000 women aged 15–44. The lowest rate is in the Netherlands (5/1000), which has one of the world’s most liberal abortion laws.9 This contrasts with the former USSR, which had officially reported rates of 112/1000 in the mid-1980s.13 In Western countries, abortion rates peak at about age 20. Women under 25 years of age obtain 56% of abortions in England and Wales and 61% of abortions in the USA.9 It is interesting to note that, while the rate of premarital sex is similar in North America and Western Europe, the rate of abortions in the Netherlands is one-fifth of the US rate.9 In the Netherlands, family planning services for unmarried people are non-controversial and sex education and contraception are widely taught in schools to teenagers.

Pregnancy Counselling

What is pregnancy counselling?

GPs are often faced with the difficult situation of diagnosing pregnancy in a woman for whom such a diagnosis is not anticipated with joy or happiness. In these situations or when women present seeking advice about what to do in a situation of unplanned pregnancy, GPs need to engage in pregnancy counselling. While doctors and other health professionals are not compelled to take part in counseling or to arrange or perform an abortion if they have religious or other objections to it, they should not seek to impose this view on their patients and should inform them where they can seek advice from another practitioner who is prepared to discuss abortion. Indeed, recent changes to legislation in Victoria mandate this.14

How do I go about counselling a woman with an unplanned pregnancy?

At the counselling session, a GP should:

Countering the myths about abortion

A new ‘woman-centred’ anti-choice strategy opposing abortion has become increasingly apparent in the media. The strategy contends that women do not really choose abortion but are pressured into it by others and then experience a range of negative effects afterwards, including an increased risk of breast cancer, infertility and post-abortion grief.15 GPs need to be very aware of the evidence contradicting these complaints and be clear about rebutting them when counselling patients.

Does abortion lead to future infertility?

Studies have shown that first-trimester termination of pregnancy is not associated with either later infertility, increased risk of ectopic pregnancy or subsequent non-viable outcome.16–18

Does abortion lead to breast cancer?

The science behind a possible association is plausible. The current widely accepted theory about the development of breast cancer holds that mutations that lead to breast cancer come about in cells that are proliferating rather than in cells that are quiescent.19 It follows that any factor that may increase the period of time that cells spend proliferating may increase the risk of developing cancerous change. In breast tissue, cell proliferation is affected by hormonal factors, hence the research into the risk of developing breast cancer associated with the use of exogenous hormones such as hormone replacement therapy and the contraceptive pill.

One epidemiological association that has been found in relation to breast cancer is the protective effect endowed by having a full-term pregnancy.20 This may be explained by the fact that in late pregnancy breast epithelial cells differentiate (i.e. they cease to proliferate). Conversely in early pregnancy the cells proliferate. Some researchers have therefore postulated that having an abortion (induced) or a miscarriage (spontaneous) for that matter may not only eliminate the long-term protection gained by having a full-term pregnancy, but may even increase the risk of breast cancer by altering the overall balance of cellular activity towards that of proliferation.21

A large study to advance knowledge in this area actually tackled this issue by analysing data from two registries in Denmark: the National Registry of Induced Abortions and the Danish Cancer Registry. Published in 1997 in the New England Journal of Medicine,22 this study examined the relationship between induced abortion and breast cancer by looking at the experiences of 1.5 million Danish women. This study had the largest data set of all previously published work and, while no registry can be perfect, the study did not rely on reporting by the women themselves. The authors adjusted for parity and for timing and number of abortions, as well as examining the effect of gestational age at the time of the abortion. They found that having an induced abortion had no overall effect on breast cancer risk.

These findings were confirmed by the Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer,23 which brought together the worldwide epidemiological evidence on the possible relationship between breast cancer and previous spontaneous and induced abortions. They concluded that pregnancies that end as a spontaneous or induced abortion do not increase a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer, suggesting that the studies of breast cancer with retrospective recording of induced abortion yield misleading results, possibly because women who had developed breast cancer were, on average, more likely than other women to disclose previous induced abortions.

Is there such a thing as the ‘post-abortion syndrome’?

In the early 1990s, the US Surgeon General (Koop) undertook a review of the literature on the medical and psychological sequelae of abortion. The aim was to help overturn the ‘Roe vs Wade’ landmark US Supreme Court decision that legalised abortion in the USA during the first two trimesters of pregnancy, while Koop himself was publicly opposed to abortion.9 His report, which was never officially released, could not find evidence of significant adverse consequences for women undergoing abortion and expressed doubts about the existence of a post-abortion syndrome.24

These findings are confirmed by a systematic review that looked at studies published in the last 10 years.25

What the evidence does show is that, while adverse sequelae do occur in a minority of women, abortion in general does not cause deleterious psychological effects.26,27 There is no evidence that, overall, abortion causes psychiatric illness.28 The incidence of serious psychiatric illness is much higher following full-term delivery than following abortion.27 Whether abortion causes psychological distress, and the degree and course of any distress, largely depend on the baseline psychological and social condition of the patient and the circumstances under which conception occurs, whether abortion is decided upon and whether abortion is carried out.29 As the British Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologist (RCOG) concludes,30 ‘some studies suggest that rates of psychiatric illness or self-harm are higher among women who have had an abortion, compared with women who give birth and to nonpregnant women of similar age. It must be borne in mind that these findings do not imply a causal association and may reflect continuation of pre-existing conditions’.

It is important to note in this debate the facts that women who are denied an abortion are at increased risk of anxiety and other mental health problems27 and that the emotional and social costs of carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term appear to extend to the offspring.31

Summary of key points

Methods of Abortion

Surgical abortion

How safe is it to have an abortion?

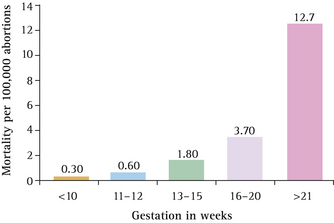

First-trimester abortion carried out by well-trained practitioners in adequate facilities is one of the safest and easiest of gynaecological procedures to carry out, with a very low risk of complications. Beyond 10 weeks’ gestation the health risks of abortion rise with each week of the pregnancy, the risks of late second-trimester abortion being three to four times higher than those in the first trimester (Fig 4.1). In countries such as Australia,32 the overwhelming majority of surgical terminations of pregnancy (96%) are carried out in the first trimester of pregnancy. In the USA, 4% are obtained at 16–20 weeks, and 1.4% at >21 weeks.33

When women ask about the safety of abortion it is also worth pointing out that in developed countries, mortality associated with childbirth is 11 times higher than that for safely performed abortion procedures and 30 times higher than for abortions of up to 8 weeks’ gestation.9

What are the indications for the procedure?

Most abortions are carried out for psychosocial reasons when an unplanned pregnancy has ensued. Many countries do insist, however, on there being a medical indication for the procedure to be carried out. Possible medical indications for abortion are listed in Table 4.1.

TABLE 4.1 Medical indications for termination of pregnancy

| Maternal indications | Fetal indications |

|---|---|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|