Fig. 1

Seventeen year-old male that sustained a medial arm laceration involving the ulnar nerve (Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children, Philadelphia). (a) Medial arm laceration. (b) Loss of flexor digitorum profundus function. (c) Inability to cross fingers. (d) Positive Froment’s sign. (e) Positive Wartenberg’s sign

Nerve Conduction Studies

Nerve conduction studies are generally of limited use in the young pediatric population, largely due to difficulties with patient compliance and tolerance. In addition, the clinically observed functional improvement may not always correspond to electrical improvement and vice versa. In addition, in order to obtain a good study, sedation is often required, which confounds the interpretation. Thus, the routine use of electrophysiologic studies in children is not universally embraced. Nevertheless, ulnar mononeuropathy is one of the more frequently seen pediatric nerve diagnoses, with the electrophysiologic prognosis being more favorable in nontraumatic causes as compared to traumatic ones (Felice and Royden Jones 1996).

In addition, two particular scenarios in children may cause altered responses with respect to the results of electrophysiologic studies. Firstly, it has been found that prenatal alcohol exposure (>2 oz. absolute alcohol/day) in young children can cause abnormalities in nerve conduction studies, with slower nerve velocities and smaller proximal and distal amplitudes as compared to controls (Avaria Mde et al. 2004). Secondly, it has also been found that nerve conduction results are altered in children with Type I diabetes mellitus. Cenesiz et al. (2003) examined electrophysiologic studies in forty children with Type I diabetes and compared the results to a control group of thirty patients. All nerve conduction values in children with diabetes mellitus were found to be significantly lower as compared to those of the control group, and overall. Sixty percent of diabetic children were found to have some type of peripheral neuropathy.

Ulnar Nerve Subluxation

Ulnar nerve subluxation at the elbow can be a cause of medial elbow pain, mostly in adults. This subluxation finding can be seen in children, although it is usually asymptomatic. Erez et al. (2012) demonstrated in an ultrasound study that 37 % of normal children had subluxating or dislocating ulnar nerves at the elbow. Patients with unstable ulnar nerves tended to be younger (aged 6–10 years) and were more likely to have generalized ligamentous laxity. Waters and colleagues also examined normal pediatric subjects and found a statistical association between young age, ligamentous laxity, and ulnar nerve instability, as well as a strong presence of bilateral ulnar nerve subluxation (Zaltz et al. 1996).

Subluxating ulnar nerves that are symptomatic may need to have treatment similar to that of cubital tunnel syndrome (Fig. 2). Most cases are asymptomatic and are simply associated with young age and ligamentous laxity. This finding can be important when considering pinning of supracondylar humerus fractures. If 10 % of all children have unstable ulnar nerves in flexion, a subluxating or dislocating ulnar nerve could be particularly at risk with a medial pin.

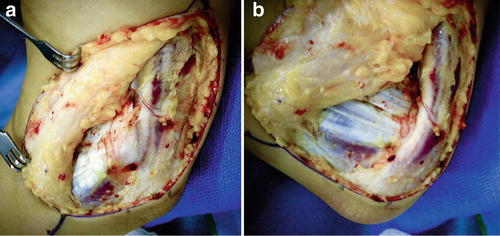

Fig. 2

Ulnar nerves that subluxate may yield symptoms requiring treatment. (a) Ulnar nerve in a resting position within the cubital tunnel. (b) Anterior subluxation with elbow flexion

Ulnar Nerve Compression

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

The ulnar nerve can be subject to compression at several sites along its course. At the elbow, the possible common sites of nerve compression are (from proximal to distal) the arcade of Struthers (an overlying fascial layer), the medial head of the triceps, the medial intermuscular septum, the medial epicondyle itself (especially if there are bony abnormalities), Osborne’s ligament (also sometimes referred to as Osborne’s band or Osborne’s fascia) that overlies the cubital tunnel, and lastly between the heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. Collectively, compression of the ulnar nerve in any of these potential areas can lead to cubital tunnel syndrome. In addition, flexion of the elbow causes flattening of the cubital tunnel, decreasing its volume and compressing the ulnar nerve.

Cubital tunnel syndrome is rare in the pediatric and adolescent population, though it has been reported in the young, throwing athlete (Godshall and Hansen 1971). In the average pediatric patient presenting with symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome, Stutz et al. (2012) found in 39 extremities that nonoperative treatment (including nighttime splinting, anti-inflammatory medication, and activity modification) was not uniformly successful, but they still recommended conservative treatment as an initial approach. They did find that patients who underwent surgical release (30 extremities) obtained good relief of symptoms. Most of the time, the etiology of cubital tunnel in the pediatric and adolescent population is idiopathic. In some cases, the cause may be related to a subluxating ulnar nerve. Less common etiologies of compression of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel area include compression by the anconeus epitrochlearis muscle (Fig. 3) (Boero et al. 2009). A single case of cubital tunnel has been reported in a child with Larsen’s syndrome and a dysplastic medial epicondyle (Tubbs et al. 2008).

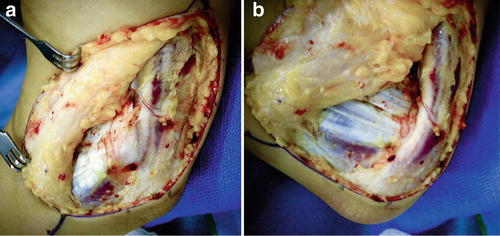

Fig. 3

Sixteen year-old male underwent right ulnar nerve decompression. An epitrochlear anconeus was found overlying the cubital tunnel (Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children, Philadelphia)

The surgical options for the treatment of cubital tunnel are similar to adults with no technique demonstrating superior efficacy. Symptomatic subluxation requires anterior transposition (Fig. 4).

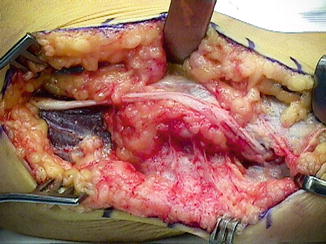

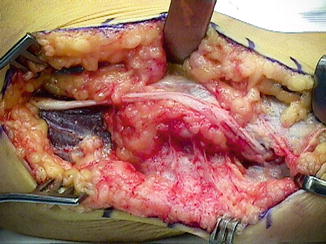

Fig. 4

Anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow

Guyon’s Canal Compression

At the wrist, the ulnar nerve can become compressed within Guyon’s canal, which is a fibro-osseous tunnel distal to the wrist flexor retinaculum where the ulnar nerve and artery enter the hand. The roof of Guyon’s canal is composed of the volar carpal ligament and the pisohamate ligament. The cause of ulnar nerve compression within Guyon’s canal can be idiopathic (most common) or due to a space-occupying lesion such as a ganglion or vascular mass (ulnar artery aneurysm). Entrapment of the ulnar nerve at Guyon’s canal in general is also rare in children. It has been reported in a case associated with exuberant scar tissue formation after a laceration over the volar ulnar wrist (Kalaci et al. 2008).

Compression by Mass Lesions

The ulnar nerve can become compressed by a mass anywhere along its course in the upper extremity. Such lesions can arise from the bone, the soft tissue, the vascular system, or the joint. Some of the more commonly seen benign masses in children include ganglion cysts and osteochondromas.

Ganglion Cysts

Ganglion cysts are thought to be outpouchings of the joint lining and are filled with synovial fluid. Most cases associated with ulnar nerve compression have been reported in the adult literature, both at the cubital tunnel/elbow region and in Guyon’s canal. Only one case has been reported in a child, in the Japanese literature, which occurred distally at the wrist (Miwa et al. 1970). Treatment of symptomatic lesions consists of excision of the mass, along with nerve exploration and decompression.

Osteochondromas

Osteochondromas in children can occur either as a singular lesion or multiple lesions (also known as multiple hereditary exostosis). They tend to occur at the physeal region of bones and actively grow until skeletal maturity, after which point the lesions become more quiescent. Lesions that occur about the elbow could have the potential to cause ulnar nerve stretch or compression, but this has not been commonly reported, with only one report in an adult in the Turkish literature (Karakurt et al. 2004). Excision of the lesion is recommended if persistent ulnar nerve symptoms arise, along with exploration and decompression of the nerve.

Other Compressions

The ulnar nerve can be at risk in the upper extremity for compression from such entities as fluid accumulation and swelling. Some of the more unusual cases of ulnar palsy reported in children due to compression include intraneural hemorrhage in a hemophiliac (Cordingly and Crawford 1984) and after intravenous fluid extravasation (Dunn and Wilensky 1984).

Injury

Fractures

Most neuropathies associated with a fracture at the time of injury are likely neuropraxic and can be monitored for recovery; however, the ulnar nerve, due to its relatively superficial location and close association with the ulnohumeral joint, has a particular risk of injury with elbow fractures. Entrapment of the ulnar nerve has been reported in an olecranon fracture (Ertem 2009) and an elbow dislocation (Reed and Reed 2012), and entrapment with laceration of the ulnar nerve has been reported in forearm fractures (Stahl et al. 1997). The following section discusses some of the more common elbow fractures that may result in ulnar nerve injury. Careful observation of the initial fracture pattern and displacement along with a meticulous physical exam, combined with a close assessment of clinical recovery, can aid in decision making regarding potential nerve exploration.

Supracondylar Humerus Fractures

Supracondylar humerus fractures are the most commonly seen elbow fractures in children. Fractures needing surgical intervention are often treated by crossed pinning, but one of the most worrisome possible complications is that of ulnar nerve injury associated with the injury itself, or from fixation of the fracture. Fracture pinning is usually performed with the elbow in the flexed position for fracture reduction, but this maneuver can cause anterior subluxation of the ulnar nerve, especially in young, lax children, which puts the ulnar nerve at direct risk during medial pinning.

One meta-analysis examining neuropraxias associated with supracondylar humerus fractures showed that the overall incidence of ulnar nerve injury with surgical treatment of supracondylar humerus fractures was 6 %. The ulnar nerve was the most frequently damaged nerve, occurring mostly in flexion-type fractures, whereas the anterior interosseous nerve was at higher risk in extension type fractures (Babal et al. 2010). Eberl et al. (2011) found a higher rate of iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury (15 %) in children treated with crossed pins as compared to .4 % in children treated by antegrade nailing. However, pinning is the most common method to surgically treat supracondylar humerus fractures, and much literature has been devoted to determining the safest and most stable pin configuration.

A few meta-analyses of pinning methods have demonstrated greater fracture stability but up to fourfold increased risk of iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury with crossed pins as compared to lateral pins (Woratanarat et al. 2012; Zhao et al. 2013), and another meta-analysis suggested there is an iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury for every 28 patients treated with crossed pinning as compared with lateral pinning (Slobogean et al. 2010). Eberl et al. (2011) also found that medial pinning conferred the highest overall risk of nerve injury, including the ulnar nerve. In patients demonstrating neuropathy associated with supracondylar humerus fractures however, most studies have shown good results in terms of nerve recovery (including median, radial, and ulnar nerves) with observation. Therefore, routine nerve exploration is not recommended particularly if a mini-open approach was used (Ramachandran et al. 2006; Khademolhosseini et al. 2013). In summary, one should be aware of the increased concern for ulnar nerve injury with a flexion-type supracondylar humerus fracture, especially with treatment by medial or crossed pinning, and use of a mini-open incision should be considered to visualize the ulnar nerve.

Medial Epicondylar Fractures

Medial epicondyle fractures are relatively uncommon, accounting for only about 20 % of total pediatric elbow fractures. The mechanism of injury can be by direct trauma, by avulsion, or associated with an elbow dislocation (roughly 60 % of medial epicondylar fractures are associated with an elbow dislocation ). Surgical indications include open fractures, an intra-articular fracture fragment, gross instability, and ulnar nerve entrapment (Fig. 5).

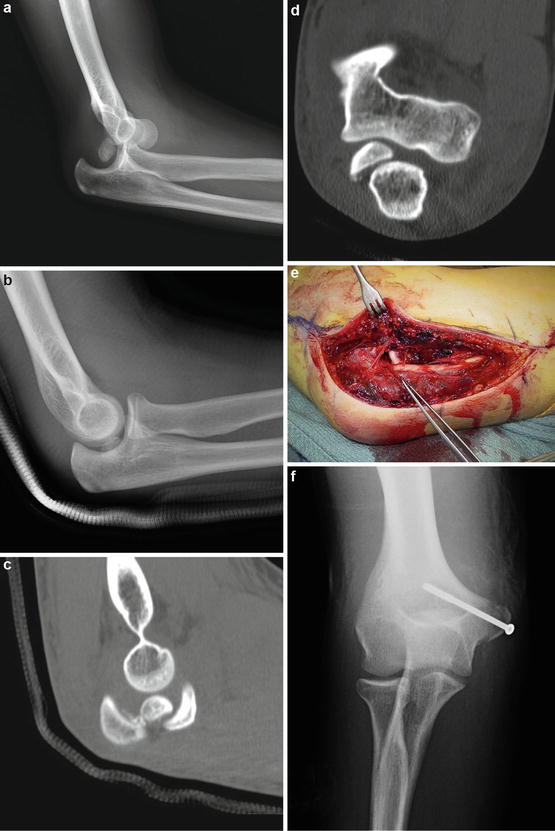

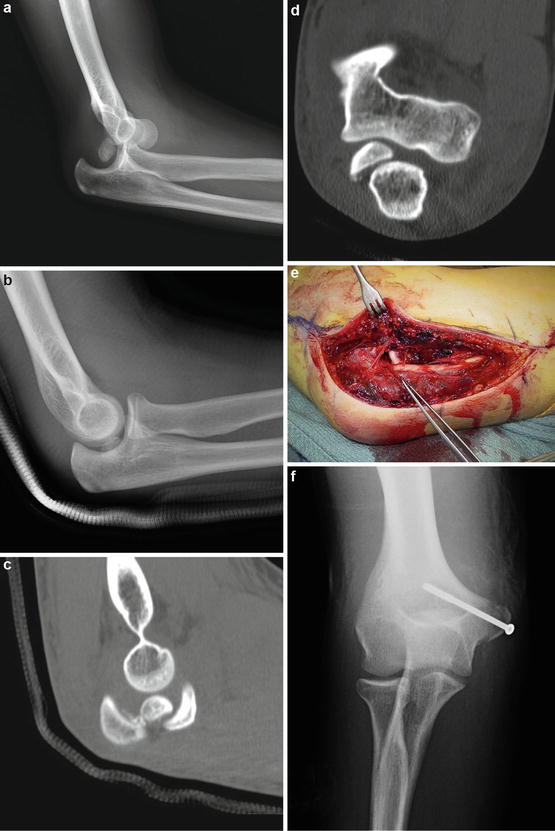

Fig. 5

Fifteen year-old right hand-dominant male dislocated right elbow (Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children, Philadelphia). (a) X-rays demonstrate posterolateral dislocation with displaced medial epicondyle fracture. (b) Following closed reduction, medial epicondylar fragment appears to be within the ulnohumeral joint. (c) Sagittal CT scan cut infers medial epicondyle within the ulnohumeral joint. (d) Coronal CT scan confirms medial epicondyle within the ulnohumeral joint. In addition, physical examination revealed absent sensation in the ring and small fingers and inability to cross his fingers or contract his first dorsal interosseous muscle. (e) Medial incision with extrication of ulnar nerve traveling into ulnohumeral joint (Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children, Philadelphia). (f) AP X-ray after fixation with a cannulated screw

The incidence of ulnar nerve injury, despite a close anatomic association with the area of injury, is relatively low. It has been recommended that the ulnar nerve be protected during fixation, but routine dissection is unnecessary (Gottschalk et al. 2012). However, if the medial epicondylar fragment is small and the injury associated with an elbow dislocation, late ulnar nerve palsy has been reported due to a trapped nerve (Haflah et al. 2010; Lima et al. 2013). Therefore, a high index of suspicion for ulnar nerve entrapment in these cases is warranted. Clinical results in treatment of medial epicondylar fractures overall are good; specifically with respect to the ulnar nerve, Kamath et al. (2009) found in their systematic review no difference in postoperative ulnar nerve symptoms between fractures treated operatively versus nonoperatively, regardless of their preoperative ulnar nerve symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree