Chapter 198 Tularemia (Francisella tularensis)

Tularemia is a zoonotic infection caused by the gram-negative bacterium Francisella tularensis. Tularemia is primarily a disease of wild animals; human disease is incidental and usually results from contact with blood-sucking insects or live or dead wild animals. The illness caused by F. tularensis is manifested by different clinical syndromes, the most common of which consists of an ulcerative lesion at the site of inoculation with regional lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis. It is also a potential agent of bioterrorism (Chapter 704).

Epidemiology

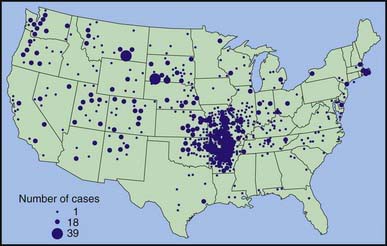

During 1990-2000, a total of 1,368 cases of tularemia were reported in the USA from 44 states, averaging 124 cases (range 86-193) per year (Fig. 198-1). Four states accounted for 56% of all reported tularemia cases: Arkansas, 315 cases (23%); Missouri, 265 cases (19%); South Dakota, 96 cases (7%); and Oklahoma, 90 cases (7%).

Clinical Manifestations

Although it may vary, the average incubation period from infection until clinical symptoms appear is 3 days (range, 1-21 days). A sudden onset of fever with other associated symptoms is common (Table 198-1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree