Chapter 207 Tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

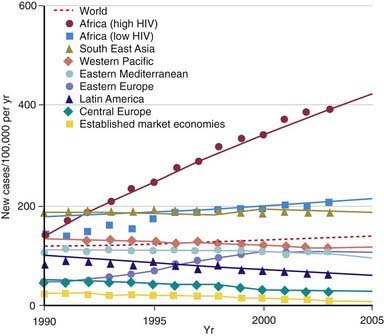

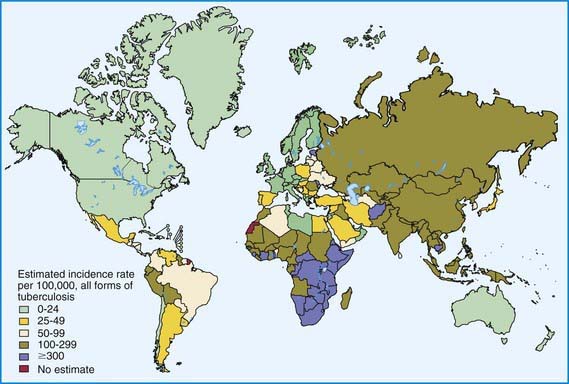

During the last decade of the 20th century the number of new cases of tuberculosis increased worldwide. Currently, 95% of tuberculosis cases occur in developing countries where HIV/AIDS epidemics have had the greatest impact and where resources are often unavailable for proper identification and treatment of these diseases (Figs. 207-1 and 207-2). In many industrialized countries, most cases of tuberculosis occur in foreign-born populations (Figs. 207-3 and 207-4). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that >8 million new cases of tuberculosis occur and that approximately 2 million people die of tuberculosis worldwide each year. Almost 1.3 million cases and 450,000 deaths occur in children each year. More than 30% of the world’s population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. If present trends continue, 10 million new cases are expected to occur annually by 2010, with Africa having more cases than any other region of the world (see Fig. 207-1). In the USA, after a resurgence in the late 1980s, the total number of cases of tuberculosis began to decrease in 1992, but tuberculosis continues to be a public health concern (see Fig. 207-3).

Figure 207-2 Distribution of tuberculosis in the world in 2003.

(From Dye C: Global epidemiology of tuberculosis, Lancet 367:938–940, 2006.)

Figure 207-3 Case rates of tuberculosis (TB), by age—USA, 1993-2008.

(From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2008. Atlanta, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, September 2009.)

Figure 207-4 Number of tuberculosis (TB) cases in U.S.-born and foreign-born persons—USA, 1993-2008.

(From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2008. Atlanta, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, September 2009.)

Epidemiology

The World Health Organization estimates that 30% of the world’s population (2 billion people) are infected with M. tuberculosis. Infection rates are highest in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (see Fig. 207-2). The global burden of tuberculosis continues to grow owing to several factors, including the impact of HIV epidemics, population migration patterns, increasing poverty, social upheaval and crowded living conditions in developing countries and in inner city populations in developed countries, inadequate health coverage and poor access to health services, and inefficient tuberculosis control programs.

Tuberculosis case rates decreased steadily in the USA during the 1st half of the 20th century, long before the advent of antituberculosis drugs, as a result of improved living conditions and, likely, genetic selection favoring persons resistant to developing disease. A resurgence of tuberculosis in the late 1980s was associated primarily with the HIV epidemic and transmission of the organism in congregate settings, adding to increased immigration and poor tuberculosis control (see Fig. 207-3). Since 1992, the number of reported cases of tuberculosis has decreased each year, reaching a record low of 12,904 cases (rate of 4.2/100,000 population) in the year 2008. Of these, 786 (6.1%) cases occurred in children <15 yr of age (rate 1.3/100,000 population). The decline in overall incidence was mostly due to a substantial decrease in cases in persons born in the USA. About 59% of all cases were among foreign-born persons. The total number of cases among foreign-born persons increased 5% between 1992 and 2005 (see Fig. 207-4). In all age groups, the proportion of reported cases was strikingly higher in foreign-born and nonwhite persons, even though the number of cases among foreign-born children <15 yr of age has declined. In white populations in the USA, tuberculosis rates are highest among the elderly who acquired the infection decades ago. In contrast, among nonwhite populations, tuberculosis is most common in young adults and children <5 yr of age. The age range of 5-14 yr is often called the “favored age,” because in all human populations this group has the lowest rate of tuberculosis disease. Among adults two thirds of cases occur in men, but in children there is no significant difference in sex distribution.

In the USA, most children are infected with M. tuberculosis in their home by someone close to them, but outbreaks of childhood tuberculosis also occur in elementary and high schools, nursery schools, daycare centers and homes, churches, school buses, and sports teams. HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis can transmit M. tuberculosis to children, and children with HIV infection are at increased risk for developing tuberculosis after infection. Specific groups are at high risk for acquiring tuberculosis infection and progressing from LTBI to tuberculosis (Table 207-1).

Table 207-1 GROUPS AT HIGH RISK FOR ACQUIRING TUBERCULOSIS INFECTION AND DEVELOPING DISEASE IN COUNTRIES WITH LOW INCIDENCE

RISK FACTORS FOR TUBERCULOSIS INFECTION

RISK FACTORS FOR PROGRESSION OF LATENT TUBERCULOSIS INFECTION TO TUBERCULOSIS DISEASE

RISK FACTORS FOR DRUG-RESISTANT TUBERCULOSIS

Pathogenesis

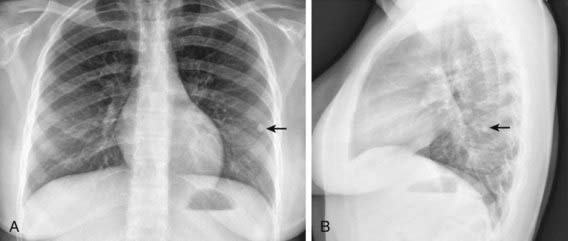

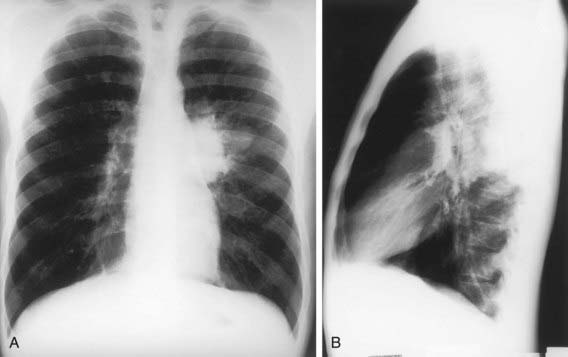

The primary complex of tuberculosis includes local infection at the portal of entry and the regional lymph nodes that drain the area (Fig. 207-5). The lung is the portal of entry in >98% of cases. The tubercle bacilli multiply initially within alveoli and alveolar ducts. Most of the bacilli are killed, but some survive within nonactivated macrophages, which carry them through lymphatic vessels to the regional lymph nodes. When the primary infection is in the lung, the hilar lymph nodes usually are involved, although an upper lobe focus can drain into paratracheal nodes. The tissue reaction in the lung parenchyma and lymph nodes intensifies over the next 2-12 wk as the organisms grow in number and tissue hypersensitivity develops. The parenchymal portion of the primary complex often heals completely by fibrosis or calcification after undergoing caseous necrosis and encapsulation (Fig. 207-6). Occasionally, this portion continues to enlarge, resulting in focal pneumonitis and pleuritis. If caseation is intense, the center of the lesion liquefies and empties into the associated bronchus, leaving a residual cavity.

(From Kaufman SHE, Hussey G, Lambert PH: New vaccines for tuberculosis. Lancet 375:2110–2118, 2010.)

The foci of infection in the regional lymph nodes develop some fibrosis and encapsulation, but healing is usually less complete than in the parenchymal lesion. Viable M. tuberculosis can persist for decades within these foci. In most cases of initial tuberculosis infection, the lymph nodes remain normal in size. However, hilar and paratracheal lymph nodes that enlarge significantly as part of the host inflammatory reaction can encroach on a regional bronchus (Figs. 207-7 and 207-8). Partial obstruction of the bronchus caused by external compression can cause hyperinflation in the distal lung segment. Complete obstruction results in atelectasis. Inflamed caseous nodes can attach to the bronchial wall and erode through it, causing endobronchial tuberculosis or a fistula tract. The caseum causes complete obstruction of the bronchus. The resulting lesion is a combination of pneumonitis and atelectasis and has been called a collapse-consolidation or segmental lesion (Fig. 207-9).

Figure 207-9 Right-sided hilar lymphadenopathy and collapse-consolidation lesions of primary tuberculosis in a 4 yr old child.

Immunity

Conditions that adversely affect cell-mediated immunity predispose to progression from tuberculosis infection to disease. Rare specific genetic defects associated with deficient cell-mediated immunity in response to mycobacteria include interleukin (IL)-12 receptor B1 deficiency and complete and partial interferon-γ (IFN-γ) receptor 1 chain deficiencies. Tuberculosis infection is associated with a humoral antibody response, which appears to play little role in host defense. Shortly after infection, tubercle bacilli replicate in both free alveolar spaces and within inactivated alveolar macrophages. Sulfatides in the mycobacterial cell wall inhibit fusion of the macrophage phagosome and lysosomes, allowing the organisms to escape destruction by intracellular enzymes. Cell-mediated immunity develops 2-12 wk after infection, along with tissue hypersensitivity (see Fig. 207-6). After bacilli enter macrophages, lymphocytes that recognize mycobacterial antigens proliferate and secrete lymphokines and other mediators that attract other lymphocytes and macrophages to the area. Certain lymphokines activate macrophages, causing them to develop high concentrations of lytic enzymes that enhance their mycobactericidal capacity. A discrete subset of regulator helper and suppressor lymphocytes modulates the immune response. Development of specific cellular immunity prevents progression of the initial infection in most persons.

Tuberculin Skin Testing

The appropriate size of induration indicating a positive Mantoux TST result varies with related epidemiologic and risk factors. In children with no risk factors for tuberculosis, skin test reactions are usually false-positive results. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) discourage routine testing of children and recommend targeted tuberculin testing of children at risk identified through periodic screening surveys conducted by the primary care provider (Table 207-2). Possible exposure to an adult with or at high risk for infectious pulmonary tuberculosis is the most crucial risk factor for children. Reaction size limits for determining a positive tuberculin test result vary with the person’s risk for infection (Table 207-3). For adults and children at the highest risk for having infection progress to disease (those with recent contact with infectious persons, clinical illnesses consistent with tuberculosis, or HIV infection or other immunosuppression), a reactive area of ≥5 mm is classified as a positive result, indicating infection with M. tuberculosis. For other high-risk groups, a reactive area of ≥10 mm is considered positive. For low-risk persons, especially those residing in communities where the prevalence of tuberculosis is low, the cutoff point for a positive reaction is ≥15 mm. An increase of induration of ≥10 mm within a 2-yr period is considered a TST conversion at any age.

Table 207-2 TUBERCULIN SKIN TEST (TST) OR INTERFERON-γ RELEASE ASSAY (IGRA) RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INFANTS, CHILDREN, AND ADOLESCENTS*

Children for whom immediate TST or IGRA is indicated†:

Children who should have annual TST or IGRA:

CHILDREN AT INCREASED RISK FOR PROGRESSION OF LTBI TO TUBERCULOSIS DISEASE

Children with other medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, malnutrition, and congenital or acquired immunodeficiencies deserve special consideration. Without recent exposure, these children are not at increased risk of acquiring tuberculosis infection. Underlying immunodeficiencies associated with these conditions theoretically would enhance the possibility for progression to severe disease. Initial histories of potential exposure to tuberculosis should be included for all of these patients. If these histories or local epidemiologic factors suggest a possibility of exposure, immediate and periodic TST should be considered. An initial TST or IGRA should be performed before initiation of immunosuppressive therapy, including prolonged steroid administration, use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists, or immunosuppressive therapy in any child requiring these treatments.

LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection.

* Bacille Calmette-Guérin immunization is not a contraindication to a TST.

† Beginning as early as 3 mo of age.

‡ If the child is well, the TST should be delayed for up to 10 wk after return.

From American Academy of Pediatrics: Red book: 2009 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 28, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 684.

Table 207-3 DEFINITIONS OF POSITIVE TUBERCULIN SKIN TEST (TST) RESULTS IN INFANTS, CHILDREN, AND ADOLESCENTS*

INDURATION ≥5 mm

Children in close contact with known or suspected contagious people with tuberculosis disease

Children suspected to have tuberculosis disease:

INDURATION ≥10 mm

Children at increased risk of disseminated tuberculosis disease:

Children with increased exposure to tuberculosis disease:

INDURATION ≥15 mm

Children ≥4 yr of age without any risk factors

* These definitions apply regardless of previous bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunization; erythema at TST site does not indicate a positive test result. Tests should be read at 48 to 72 hr after placement.

† Evidence by physical examination or laboratory assessment that would include tuberculosis in the working differential diagnosis (e.g., meningitis).

‡ Including immunosuppressive doses of corticosteroids.

From American Academy of Pediatrics: Red book: 2009 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 28, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 681.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree