Transobturator Midurethral Sling

Roxana Geoffrion

INTRODUCTION

Transobturator midurethral slings (tapes or TOT) were introduced in 2001 as an alternative to retropubic midurethral slings for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. The primary difference is that the TOT avoids the retropubic space by exiting the pelvis through the Obturator foramen onto the upper thigh. There are several types of transobturator slings that differ based on how the sling is placed. It can be placed with an inside-out or an outside-in technique, depending on whether the sling tunneler is passed starting through the vaginal incision or through the inner thigh incision, respectively. The TOT sling should not be confused with the second generation mini-slings, which do not penetrate the muscles of the thigh or the obturator foramen. Presently, there is minimal data defining the safety and efficacy of the mini slings and they are not covered in this book as they are currently under investigation.

There are many studies comparing TOT slings with other established surgical techniques for stress incontinence. The TOT supports the urethra like a hammock and avoids the retropubic space at insertion. This has resulted in clinical advantages of less voiding dysfunction and fewer irritative symptoms as well as fewer intraoperative complications of bladder and bowel perforation. On the other hand, the TOT is associated with increased groin/thigh pain and its location closer to the surface of the vaginal mucosa may cause more mesh erosions in the long term. Subjective efficacy of the TOT at correcting stress urinary incontinence is similar to retropubic slings, while objective efficacy is slightly inferior. Evidence of clinical efficacy is lacking beyond 5 years from the initial operation. The TOT also seems to be inferior to retropubic slings in selected groups of patients such as those suffering from intrinsic sphincteric deficiency (ISD).

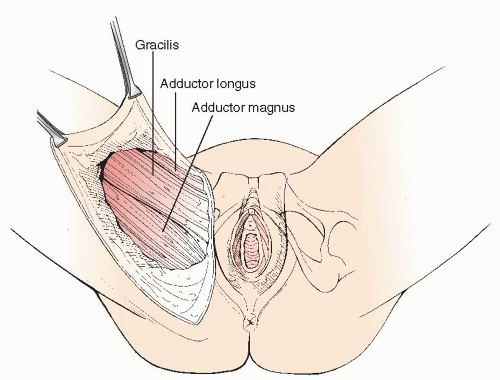

Gynecologic surgeons performing TOT must familiarize themselves with the obturator space anatomy, as this is an area where gynecologic surgery is rarely performed (Figure 32.1). The TOT outside-in tunneler is inserted through and around adductor muscles of the thigh. After penetrating the skin, the tunneler next encounters the gracilis muscle and its broad attachment to the inferior pubic ramus. It then continues between attachments of adductor magnus to inferior pubic ramus and adductor longus to superior pubic ramus. Deep to magnus and longus lie the adductor brevis and obturator externus muscles, which are also penetrated by the tunneler. The tunneler then passes through the obturator foramen (and membrane) to pierce obturator internus and turn the corner around the inferior pubic ramus until it emerges through the vaginal incision. The innervation to the adductor muscles of the thigh is provided by the obturator nerve, which passes through the obturator canal at the superior edge of the obturator foramen. On the other hand, the obturator internus muscle is an abductor muscle and its innervation is supplied by the nerve to obturator internus which lies deep in the pelvis. The obturator canal, with its rich vasculature and nerves, is a structure to be avoided when a TOT is placed. On average, the distance between tunneler and canal is 2.3 cm.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

The most important preoperative preparation for a TOT sling is to ensure the proper diagnosis of stress urinary incontinence. There are several guidelines available that define the necessary diagnostic criteria, which do not routinely require urodynamics, provided that the symptoms of urinary loss with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure is present and leakage can be demonstrated with a stress test.

If ISD is suspected as an etiologic cause for the patient’s stress urinary incontinence, urodynamics should be obtained, including valsalva leak point pressures and/or urethral pressure profilometry to assess the sphincteric function. If ISD is indeed present, the patient is best served by a retropubic sling. However, if hypermobility is the cause for the patient’s stress incontinence, a TOT is a good treatment option.

Patients should be counseled that TOT placement is a day surgery and that a Foley catheter may be necessary in cases of postoperative voiding dysfunction. The need for a postoperative Foley catheter is usually transient and short-lived; however, in patients at high risk for voiding dysfunction, consideration should be given to self-catheterization teaching preoperatively.

Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered prior to incision. A first-generation cephalosporin is the first choice, but clindamycin, erythromycin, or metronidazole are also acceptable choices in patients allergic to penicillin or cephalosporins. An assessment of risk for deep venous thromboembolism is indicated. Sequential compression devices are necessary in patients at high risk for deep vein thrombosis. Due to the short case length, most patients do not require thromboembolic prophylaxis.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

In preparation for TOT, the patient is placed in comfortable dorsal lithotomy position, with the edge of her hips just over the edge of the operating table. Excessive hip flexion and knee extension are avoided to prevent injury to the femoral and sciatic nerves. However, some flexion of the hip is desirable, so that the thighs bend back over the abdomen, leaving an angle of >60° between the thigh and abdomen. The procedure is tolerated under general, regional, or local anesthesia with sedation. The patient’s skin is prepared with a surgical scrub solution from the lower abdomen to the upper medial thighs, bilaterally; an

internal vaginal scrub is also required. Surgical lights are directed onto the surgical field. The bladder is emptied.

internal vaginal scrub is also required. Surgical lights are directed onto the surgical field. The bladder is emptied.

Surgery begins with the incisions in the inner thigh. Palpation of anatomical landmarks helps to plan the thigh incisions. The adductor longus tendon is the most obvious landmark. The notch just below this tendon, just outside the labia majora and at the level of the clitoris can be marked using a sterile pen. Local anesthetic with a vasoconstrictive agent is injected beneath the skin down to the obturator foramen and small stab incisions are made with a scalpel at these previously landmarked inner thigh locations (Figure 32.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree