Fig. 56.1

A T-tube may be used instead of a tracheotomy tube for special circumstances, such as after surgery on the larynx or trachea

Fig. 56.2

Silver tracheotomy tube, containing an inner cannula, and an obturator for use during replacement of the tube

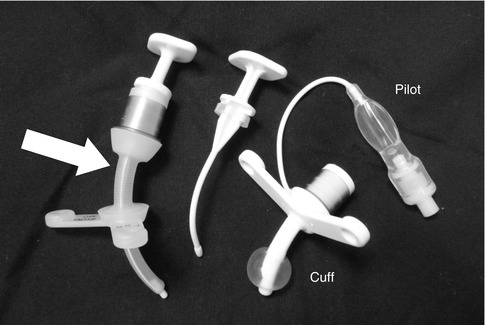

Cuffless tubes are used for most pediatric patients with tracheostomies (Fig. 56.3), with an air leak around the tracheal tube used to preserve vocalization on exhalation. Patients with less compliant lungs often require a cuff to attain adequate inflation pressures for the lungs. Cuffs can be inflated with air or sterile water, depending on the manufacturer’s recommendation. Saline should not be used to inflate cuffs because they can form crystals that clog the inflation/deflation valve. Self-expanding foam cuffs are not commonly used.

Fig. 56.3

The tracheotomy tube on the left contains an obturator and has extension external to the flange (arrow). The tracheotomy tube on the right has an inflated cuff, inflated through the port at the pilot. The middle item is the obturator for the cuffed tracheotomy tube

Speaking valves are devices which fit on the end of the tracheotomy and contain a soft plastic flap that allows air to flow in through the tracheotomy during inspiration but prevents air from flowing out through the tracheotomy during expiration. This forces the air to egress though the vocal folds, thereby supporting phonation, effective cough, and Valsalva maneuvers. Speaking valves have been used for patients as young as 13 days of age (Engleman and Turnage-Carrier 1997) and for patients who require mechanical ventilation (Hull et al. 2005). A speaking valve is contraindicated in patients with severe subglottic stenosis or other lesions that might cause air-trapping. Some patients spontaneously learn to accomplish this same objective of forcing expiration through the vocal folds, either by occluding the end of the tracheotomy tube manually or by using their chins.

Mechanical issues may also be important. The external connector to a bag-mask device or mechanical ventilator tubing is universally sized but often is rather large relative to the neck of an infant and may interfere with normal head positioning or cause pressure at the stoma. Some tracheotomy tubes incorporate an extension which increases the distance between the universal adaptor and the tracheotomy flange, allowing more normal head positioning. The connections between the tracheotomy adaptor and the ventilator tubing can loosen, leak, or disconnect, particularly while turning or repositioning a patient. Extra caution to prevent disconnection or even decannulation is indicated if the patient requires extreme head positioning or if head turning is required for access to the lateral neck (e.g., for internal jugular central venous catheter placement). Some surgeons suture the tracheotomy flange to the skin of the neck for new tracheotomies; in this case scissors or a scalpel should be immediately available in case there is an emergency, such as a tracheotomy plug or tracheotomy displacement, requiring tracheostomy tube removal and replacement.

56.2 Indications

Pediatric tracheostomies can bypass upper and central airway obstruction and facilitate mechanical ventilation including positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) delivery to lower airways and facilitate eating, aerosol delivery, suctioning, and tracheobronchial toilet (Mahadevan et al. 2007; Davis 2006; Carron et al. 2000; Parrilla et al. 2007). Whether or not a tracheostomy tube can prevent pulmonary aspiration, even when the cuff is properly inflated, is controversial.

In adults, a large proportion of tracheotomies are performed to support long-term mechanical ventilation (Goldenberg et al. 2002). In contrast, many authors assert that most pediatric tracheotomies are performed to bypass various causes of upper airway obstruction (Goldenberg et al. 2002; Parrilla et al. 2007; Trachsel and Hammer 2006; Mahadevan et al. 2007; Davis 2006). Comparisons between reported series are limited by a lack of standardized system of classification.

In children, upper and central airway obstruction can be caused by a large variety of congenital or acquired lesions, affecting any aspect of the respiratory system proximal to the trachea, from the anterior nares to the subglottis. Examples of abnormalities which interfere with breathing include conditions which affect the mouth and nose, such as Robin sequence or other craniofacial abnormalities; lesions that affect the larynx directly, such as severe laryngomalacia and vocal fold paralysis; and lesions that have variable locations in the airway, such as neoplasms like hemangiomas and lymphangiomas (Table 56.1). Airway obstruction can result from infection and from physical, chemical, or burn-induced trauma, as well as from conditions restricting lung excursion, such as campomelic dysplasia or morbid obesity.

Mahadevan et al. (New Zealand) | Patients (%) | Davis | Patients (%) | Parrilla et al. (Italy) | Patients (%) | Carron et al. (USA) | Patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Airway and air-way related | Airway obstruction | 86 (70) | Unsafe or obstructed airway | 36 (55) | 38 (100) | Upper airway obstruction | 38 (19) | |

Craniofacial dysmorphism | 40 (33) | Subglottic stenosis | 13 (20) | Neuromuscular or respiratory problems | 17 (45) | Subglottic stenosis | 13 (6) | |

Subglottic stenosis | 18 (15) | Subglottic hemangioma | 4 (6) | Congenital malformations (4 laryngotracheal anomaly, 3 cardiovascular anomaly, 1 pulmonary anomaly) | 8 (21) | Tracheomalacia | 8 (4) | |

CNS | 6 (5) | Vocal cord palsy | 4 (6) | Craniofacial syndromes/Obstructive sleep apnea syndromes | 6 (16) | Pharyngeal stenosis | 2 (1) | |

Vocal cord palsy | 6 (5) | Other (craniofacial syndromes, glossoptosis, pharyngeal, hypotonia, epiglottitis) | 15 (23) | Acquired subglottic stenosis | 5 (13) | Subglottic hemangioma | 2 (1) | |

Hemangioma | 5 (4) | Tracheoesophageal burn | 1 (3) | Tracheal stenosis | 2 (1) | |||

Laryngomalacia | 4 (3) | Trauma | 1 (3) | Other | 11 (5) | |||

Cavernous lymphangioma | 4 (3) | Craniofacial syndromes | 27 (13) | |||||

Other | 3 (2) | Pierre-Robin sequence | 5 (2) | |||||

Treacher Collins disease | 5 (2) | |||||||

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome | 3 (1) | |||||||

Nager syndrome | 2 (1) | |||||||

Other | 5 (2) | |||||||

Trauma | 15 (7) | |||||||

Closed head injury | 12 (6) | |||||||

Laryngeal fracture | 1 (<1) | |||||||

Laryngeal or tracheal injury | 1 (<1) | |||||||

Cervical spine fracture | 1 (<1) | |||||||

Vocal fold paralysis | 15 (7) | |||||||

Hydrocephalus | 3 (1) | |||||||

Sandhoff disease | 1 (<1) | |||||||

Leukodystrophy | 1 (<1) | |||||||

Neurofibromatosis | 1 (<1) | |||||||

Mobius syndrome | 1 (<1) | |||||||

Idiopathic or unspecified | 7 (3) | |||||||

Prolonged ventilation | Prolonged ventilation | 36 (30) | Mechanical ventilation | 15 (23) | Prolonged intubation | 53 (26) | ||

Trauma | 9 (7) | Central nervous system abnormality | 5 (8) | Prematurity or BPD | 37 (18) | |||

Postoperative | 9 (7) | Cyanotic heart disease | 4 (6) | Congenital heart disease | 3 (1) | |||

Infection | 8 (7) | Respiratory failure | 4 (6) | Pneumonia | 2 (1) | |||

Neurological | 4 (3) | Respiratory infection | 1 (2) | Other | 11 (5) | |||

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 3 (2) | Sepsis | 1 (2) | |||||

Ondine’s curse | 3 (2) | |||||||

Tracheobronchial toilet | Tracheobronchial toilet, aspiration risk | 14 (22) | Neurologic impairment | 56 (27) | ||||

Trauma-related head injury | 10 (15) | Cerebral palsy | 18 (9) | |||||

Hypoxic brain injury | 2 (3) | Hypoxic encephalopathy | 4 (2) | |||||

Intracerebral hemorrhage | 1 (2) | Werdnig-Hoffmann syndrome | 4 (2) | |||||

Respiratory infection | 1 (2) | Spina bifida | 3 (1) | |||||

Myasthenia gravis | 2 (1) | |||||||

Encephalopathy – unspecified | 6 (3) | |||||||

Other | 16 (8) | |||||||

Total | 122 (100 %) | 65 (100 %) | 38 (100 %) | 204 (100 %) | ||||

Many conditions which interfere with ventilation in infants, such as severe tracheomalacia, are expected to improve over time. In contrast, chronic neuromuscular disease, such as muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, or severe developmental delays which interfere with the patient’s ability to breathe, swallow, cough effectively, or otherwise protect his airway, may progress over time. The majority of pediatric tracheotomies are performed in children less than 1 year of age (Mahadevan et al. 2007; Carron et al. 2000).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree